Louis Veuillot: Difference between revisions

Alistair1978 (talk | contribs) m typo (via WP:JWB) |

|||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|French journalist and author}} |

|||

{{Infobox writer |

{{Infobox writer |

||

| name = Louis Veuillot |

| name = Louis Veuillot |

||

| Line 4: | Line 5: | ||

| caption = Veuillot, by Nadar, 1873 |

| caption = Veuillot, by Nadar, 1873 |

||

| birth_date = 11 October 1813 |

| birth_date = 11 October 1813 |

||

| birth_place = [[Boynes]], Loiret Department, France |

| birth_place = [[Boynes]], [[Loiret|Loiret Department]], [[First French Empire|France]] |

||

| death_date = 7 March 1883 (aged 70) |

| death_date = 7 March 1883 (aged 70) |

||

| death_place = Paris, France |

| death_place = [[Paris]], [[French Third Republic|France]] |

||

| nationality = French |

| nationality = French |

||

| spouse = Mathilde |

| spouse = Mathilde |

||

| Line 15: | Line 16: | ||

| period = |

| period = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Conservatism |

{{Conservatism in France|Intellectuals}} |

||

'''Louis Veuillot''' (11 October 1813 – 7 March 1883) was a French journalist and author who helped to popularize [[ultramontanism]] (a philosophy favoring Papal supremacy). |

'''Louis Veuillot''' (11 October 1813 – 7 March 1883) was a French journalist and author who helped to popularize [[ultramontanism]] (a philosophy favoring Papal supremacy). |

||

==Career overview== |

==Career overview== |

||

Veuillot was born of humble parents in [[Boynes]] ([[Loiret]]). When he was five years of age, his parents relocated to Paris. With little education, he gained employment in a lawyer's office, and was sent in 1830 to serve with a newspaper of [[Rouen]], and afterwards to [[Périgueux]]. |

Veuillot was born of humble parents in [[Boynes]] ([[Loiret]]). When he was five years of age, his parents relocated to Paris. With little education, he gained employment in a lawyer's office, and was sent in 1830 to serve with a newspaper of [[Rouen]], and afterwards to [[Périgueux]]. Initially, Veuillot supported the [[July Monarchy]] of [[Louis Phillippe]] criticizing both Republicans and supporters of the deposed [[Bourbon Dynasty]].{{sfn|Gurian|1951|p=387}} |

||

He returned to Paris in 1837, and a year later visited Rome during [[Holy Week]]. There he embraced [[ultramontane]] sentiments, and became an ardent champion of [[Catholic Church|Catholicism]]. The results of his conversion were published in ''Pélerinages en Suisse'' (1839), ''Rome et Lorette'' (1841) and other publications.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} Veuillot's embrace of Ultramontanism led to his violent rejection of Bourgeois society and norms.{{sfn|Gurian|1951|p=388–389}} He had little regard for theological nuance and held fast to the overall philosophies of [[Joseph de Maistre]] and [[Louis de Bonald]], the original Catholic [[counter-revolutionary]] thinkers.{{sfn|Gurian|1951|p=387–388}} |

|||

In |

In 1840, Veuillot joined the staff of the newspaper ''Univers Religieux'', a journal created in 1833 by [[Jacques Paul Migne|Abbé Migne]], and soon helped make it the leading organ of ultramontane propaganda as ''[[L'Univers]]''. His methods of journalism, which made great use of [[irony]] and ad hominem criticism,<ref>"In Paris M. Louis Veuillot has given us another shameful specimen of Ultramontanism. Not satisfied with comparing savants to the phylloxera, he likens Protestantism to a loathsome disease whose name is usually confined to medical works." — [https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1875/08/16/79089483.pdf "The Jesuits in France,"] ''The New York Times'', August 16, 1875, p. 4.</ref> had already provoked more than one duel, and he was imprisoned for a brief time for his polemics against the [[University of Paris]]. In 1848, he became editor of the newspaper, which was suppressed in 1860,<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/1860/04/20/news/topics-paris-greater-excommunication-emperor-pope-new-italian-kingdom-new-consul.html?scp=9&sq=%22Louis+Veuillot%22&st=p "The Greater Excommunication, The Emperor and the Pope,"] ''The New York Times'', April 20, 1860.</ref> but revived in 1867, when Veuillot resumed his ultramontane propaganda, causing a second suppression of his journal in 1874.<ref>[https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1874/09/24/82411910.pdf "The Clerical Press and Marshall Serrano,"] ''The New York Times'', September 24, 1874.</ref> Veuillot then occupied himself by writing polemical pamphlets<ref>"An impetuous, brutal journalist, whose ''verve'' and ardour came from Rabelais and Voltaire through Joseph de Maistre, Louis Veuillot was at the same time an exquisite writer and a violent Christian; he distributed holy water as though it were vitriol and handled the crucifix like a club." — Hanotaux, Gabriel (1905). [https://archive.org/stream/contemporaryfran02hanouoft#page/n3/mode/2up ''Contemporary France.''] London: Archibald Constable & Co., p. 622.</ref> against [[liberal Catholicism|liberal Catholics]], the [[Second French Empire]] and the Italian government. |

||

His services to the [[papal see]] were recognized by [[Pope Pius IX]], on whom he wrote (1878) a monograph.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

His services to the [[papal see]] were recognized by [[Pope Pius IX]], on whom he wrote (1878) a monograph.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

||

[[Matthew Arnold]] said of him: |

[[Matthew Arnold]] said of him: |

||

| Line 33: | Line 35: | ||

Some of his papers were collected in ''Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires'' (12 vols., 1857–1875), and his ''{{lang|fr|Correspondance}}'' (7 vols., 1883–85) has great political interest. His younger brother, Eugène Veuillot, published (1901–1904) a comprehensive and valuable life, ''Louis Veuillot''. |

Some of his papers were collected in ''Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires'' (12 vols., 1857–1875), and his ''{{lang|fr|Correspondance}}'' (7 vols., 1883–85) has great political interest. His younger brother, Eugène Veuillot, published (1901–1904) a comprehensive and valuable life, ''Louis Veuillot''. |

||

After the [[First Vatican Council]], Veuillot's influence began to wane. In 1879 Pope Pius IX{{clarify|date=December 2023|Pius IX already dead, or is the date wrong?}} released a letter praising him, but also regretting his "bitter zeal" in advocating his views. Among the lower clergy Veuillot retained influence. Politically he returned to advocating the restorations of the Bourbon Monarchy under [[Henri, Count of Chambord]].{{sfn|Gurian|1951|p=407–408}} |

|||

==Anti-Semitism== |

==Anti-Semitism== |

||

Veuillot was a virulent anti-Semite. As early as the 1840s, he wrote articles in ''L'Univers'' defaming Jews, portraying them as alien vagabonds, accusing them of [[blood libel]], and asserting that the Talmud commanded Jews to hate all Christians.<ref name="Levy">{{cite book |last1=Levy |first1=Richard S. |title=Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1 |date=2005 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |page=738}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kaplan |first1=Zvi Jonathan |title=Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea?: French Jewry and the Problem of Church and State |date=2009 |publisher=Society of Biblical Lit |page=65}}</ref> He contemptuously dismissed Jews who criticized him as "the deicide people", claiming they were a foreign element which plotted to control all of French society.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Michael |first1=R. |title=A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church |date=2008 |publisher=Springer |page=128}}</ref> Veuillot's hatred intensified during the [[Mortara case]] to the point where it put him at odds with [[Napoleon III]] whom he had previously supported, causing the latter to temporarily suppress the journal.<ref name="Levy" /> Veuillot's two-pronged assault on the Jews and liberalism would influence the anti-Semitism of [[Édouard Drumont]], who worked for ''L'Univers'' in his youth. |

Veuillot was a virulent anti-Semite. As early as the 1840s, he wrote articles in ''L'Univers'' defaming Jews, portraying them as alien vagabonds, accusing them of [[blood libel]], and asserting that the Talmud commanded Jews to hate all Christians.<ref name="Levy">{{cite book |last1=Levy |first1=Richard S. |title=Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1 |date=2005 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |page=738}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kaplan |first1=Zvi Jonathan |title=Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea?: French Jewry and the Problem of Church and State |date=2009 |publisher=Society of Biblical Lit |page=65}}</ref> He contemptuously dismissed Jews who criticized him as "the deicide people", claiming they were a foreign element which plotted to control all of French society.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Michael |first1=R. |title=A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church |date=2008 |publisher=Springer |page=128}}</ref> Veuillot's hatred intensified during the [[Mortara case]] to the point where it put him at odds with [[Napoleon III]] whom he had previously supported, causing the latter to temporarily suppress the journal.<ref name="Levy" /> Veuillot's two-pronged assault on the Jews and liberalism would influence the anti-Semitism of [[Édouard Drumont]], who worked for ''L'Univers'' in his youth.{{sfn|Arnoulin|1902|p=73–75}} Drumont, who in his turn was an employer of [[Charles Maurras]], was admired by [[Karl Lueger]], whom [[Adolf Hitler]] acknowledged as an influence in ''[[Mein Kampf]]''.{{sfn|Birnbaum|1993|p=72}} |

||

==Legacy== |

|||

A misattributed quote to Veuillot, "When I am weaker than you, I ask you for freedom because that is according to your principles; when I am stronger than you, I take away your freedom because that is according to my principles", is quoted in [[Frank Herbert]]'s [[Children of Dune]]. |

|||

==Works== |

==Works== |

||

| Line 55: | Line 62: | ||

* [https://archive.org/stream/couleuvres00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''Les Couleuvres,''] Victor Palmé, 1869. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/couleuvres00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''Les Couleuvres,''] Victor Palmé, 1869. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/corbinetdaubecou00veuiuoft#page/n7/mode/2up ''Corbin et d'Aubecourt,''] Victor Palmé, 1869. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/corbinetdaubecou00veuiuoft#page/n7/mode/2up ''Corbin et d'Aubecourt,''] Victor Palmé, 1869. |

||

* [https://books.google.com/books?id=-V4NAAAAYAAJ |

* [https://books.google.com/books?id=-V4NAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA3 ''La Liberté du Concile,''] Victor Palmé, 1870. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/parispendantles00veuigoog#page/n5/mode/2up ''Paris Pendant les Deux Sièges,''] Victor Palmé, 1871. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/parispendantles00veuigoog#page/n5/mode/2up ''Paris Pendant les Deux Sièges,''] Victor Palmé, 1871. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/leparfumderom01veui#page/n5/mode/2up ''Le Parfum de Rome,''] Victor Palmé, 1871. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/leparfumderom01veui#page/n5/mode/2up ''Le Parfum de Rome,''] Victor Palmé, 1871. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu10veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up ''Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires,''] [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesrelig02veui#page/n7/mode/2up Tome II], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu09veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up Tome III], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesrelig04veui#page/n7/mode/2up Tome IV], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu07veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up Tome V], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligie06veuiuoft#page/n5/mode/2up Tome VI], L. Vivés, |

* [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu10veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up ''Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires,''] [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesrelig02veui#page/n7/mode/2up Tome II], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu09veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up Tome III], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesrelig04veui#page/n7/mode/2up Tome IV], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligieu07veuigoog#page/n9/mode/2up Tome V], [https://archive.org/stream/mlangesreligie06veuiuoft#page/n5/mode/2up Tome VI], L. Vivés, 1857–1875. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/molireetbourda00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''Molière et Bourdaloue,''] Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1877. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/molireetbourda00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''Molière et Bourdaloue,''] Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1877. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/laguerreetlhomme00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''La Guerre et l'Homme de Guerre,''] Victor Palmé, 1878. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/laguerreetlhomme00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''La Guerre et l'Homme de Guerre,''] Victor Palmé, 1878. |

||

| Line 71: | Line 78: | ||

* [https://archive.org/stream/lifeofourlordjes00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ.''] New York: Peter F. Collier, 1878. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/lifeofourlordjes00veui#page/n7/mode/2up ''The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ.''] New York: Peter F. Collier, 1878. |

||

* [https://archive.org/stream/stephanietrbyjb00veuigoog#page/n2/mode/2up ''Stephanie.''] Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1883. |

* [https://archive.org/stream/stephanietrbyjb00veuigoog#page/n2/mode/2up ''Stephanie.''] Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1883. |

||

* |

* "The Essence of Giboyer (A Retort to 'Giboyer's Son')." In: ''The Universal Anthology'', Vol. XXVII. London: The Clarke Company, Ltd., 1899. |

||

* In Béla Menczer (Ed.), ''Catholic Political Thought, |

* In Béla Menczer (Ed.), ''Catholic Political Thought, 1789–1848'', University of Notre Dame Press, 1962. |

||

** "[https://archive.org/stream/catholicpolitica00menc#page/196/mode/2up The True Freedom of Thought]," pp. 196–205. |

** "[https://archive.org/stream/catholicpolitica00menc#page/196/mode/2up The True Freedom of Thought]," pp. 196–205. |

||

* ''The Liberal Illusion.'' Kansas City, Mo.: Angelus Press, 2005. |

* ''The Liberal Illusion.'' Kansas City, Mo.: Angelus Press, 2005. |

||

===Quotations=== |

|||

"It is easy to see where North America stands at present, and whither it is tending. Its rapid progress, due to the most degrading works, has fascinated Europe; but the results of this progress, exclusively material, already appear. Barbarism, profligacy, general bankruptcy, systematic destruction of the native races, idiotic slavery of the conquerors, bound to the most trying and repulsive of lives under the yoke of their own machinery. America might founder in the ocean once for all, and the human race would suffer no loss thereby. Not a saint, not an artist, not a thinker has it produced, unless one may term thought the aptitude for twisting iron for the construction of freight trains. The priests who wear out their lives there cannot create a civilization. Thus far there is no civilization in America, and as far as appearances go, there never will be." (''L'Univers'') |

|||

"Newspapers have become such a danger that it is necessary to create many. You cannot contend against the Press, except through its multitude. Add flood to flood, and let them drown one another, forming no more than a swamp, or, if you will, a sea. The swamp has its lagoons, the sea its moments of slumber. We will see whether it is possible to build some Venice within it." |

|||

"When I voted, my equality tumbled into the box with my ballot; they disappeared together." |

|||

"If I could re-establish a class of nobles, I should do so at once, and I would not belong to it." |

|||

"Amongst the amusements of Paris must be counted duels between journalists." |

|||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<gallery widths=" |

<gallery widths="180" heights="180" perrow="4"> |

||

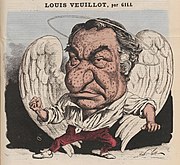

File:Louis Veuillot, by André Gil.jpg|Caricature of Louis Veuillot, by André Gil, from ''La Lune,'' 21 April 1867. |

File:Louis Veuillot, by André Gil.jpg|Caricature of Louis Veuillot, by André Gil, from ''La Lune,'' 21 April 1867. |

||

File:Portrait of Louis Veuillot.jpg|Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

File:Portrait of Louis Veuillot.jpg|Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

||

File:Louis Veuillot.jpg|Picture by Nadar, 1850s. |

File:Louis Veuillot.jpg|Picture by Nadar, 1850s. |

||

File:L. Veuillot.jpg|Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

File:L. Veuillot.jpg|Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

File:La Petite Lune - |

File:La Petite Lune - 02.jpg|''"Pâquerette."'' Caricature of Louis Veuillot, ''La Petite Lune,'' No. 2, 1878–1879. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Louis Veuillot 2.jpg|Picture of Louis Veuillot, During the 1870s. |

File:Louis Veuillot 2.jpg|Picture of Louis Veuillot, During the 1870s. |

||

File:Louis Veuillot, by Nadar.jpg|Pictures of Louis Veuillot, by Nadar, 1856. |

File:Louis Veuillot, by Nadar.jpg|Pictures of Louis Veuillot, by Nadar, 1856. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Centenary of Louis Veuillot.jpg|Centennial Celebration of the Birth of Louis Veuillot, 5 October 1913. |

File:Centenary of Louis Veuillot.jpg|Centennial Celebration of the Birth of Louis Veuillot, 5 October 1913. |

||

File:Veuillot's House.jpg|Louis Veuillot Birthplace, in Boynes, Loiret, n.d. |

File:Veuillot's House.jpg|Louis Veuillot Birthplace, in Boynes, Loiret, n.d. |

||

File:Veuillot's Tombstone.jpg|Veuillot's Tombstone, Montparnasse Cemetery, n.d. |

File:Veuillot's Tombstone.jpg|Veuillot's Tombstone, Montparnasse Cemetery, n.d. |

||

File:Louis Veuillot and his Family.jpg|Veuillot, his two Daughters, Agnès and Marie, and his Sister, Élise, 1858. |

File:Louis Veuillot and his Family.jpg|Veuillot, his two Daughters, Agnès and Marie, and his Sister, Élise, 1858. |

||

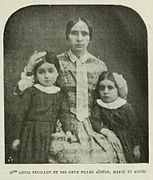

File:Veuillot's Wife and Daughters.jpg|Wife and Daughters of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

File:Veuillot's Wife and Daughters.jpg|Wife and Daughters of Louis Veuillot, n.d. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 128: | Line 107: | ||

* [[Henri, Count of Chambord]] |

* [[Henri, Count of Chambord]] |

||

* [[Our Lady of La Salette]] |

* [[Our Lady of La Salette]] |

||

* [[Catholic Church in France]] |

|||

* [[Ultramontanism]] |

|||

* [[Pope Pius IX]] |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

| Line 133: | Line 115: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{EB1911|wstitle= Veuillot, Louis| volume=28 }} |

*{{EB1911|wstitle= Veuillot, Louis| volume=28 }} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* Ages, Arnold (1974). "Veuillot and the Talmud," ''Jewish Quarterly Review'' '''64''', pp. 229–260. |

* Ages, Arnold (1974). "Veuillot and the Talmud," ''Jewish Quarterly Review'' '''64''', pp. 229–260. |

||

* Allison, John M.S. (1916). [https://archive.org/stream/churchstateinrei00alli#page/n1/mode/2up ''Church and State in the Reign of Louis Philippe.''] Princeton University Press. |

* Allison, John M.S. (1916). [https://archive.org/stream/churchstateinrei00alli#page/n1/mode/2up ''Church and State in the Reign of Louis Philippe.''] Princeton University Press. |

||

* {{citation |last=Arnoulin |first=Stéphane |title=M. Edouard Drumont et les Jesuites |date=1902 |publisher=Librairie des Deux-Mondes |location=Paris}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{citation |last=Birnbaum |first=Pierre |title=Dreyfus avant Dreyfus : Drumont et la mise en scène de l'affaire |journal=Mil neuf cent. Revue d'histoire intellectuelle |volume=11 |year=1993 |pages=71–76 |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/mcm_1146-1225_1993_num_11_1_1084}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* Cornut, Etienne (1891). [https://archive.org/stream/louisveuillott00corn#page/n7/mode/2up ''Louis Veuillot.''] Paris: Victor Retaux et Fils. |

* Cornut, Etienne (1891). [https://archive.org/stream/louisveuillott00corn#page/n7/mode/2up ''Louis Veuillot.''] Paris: Victor Retaux et Fils. |

||

* Corrigan, Raymond (1938). [https://archive.org/stream/churchandthenine028162mbp#page/n9/mode/2up ''The Church in the Nineteenth Century.''] Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company. |

* Corrigan, Raymond (1938). [https://archive.org/stream/churchandthenine028162mbp#page/n9/mode/2up ''The Church in the Nineteenth Century.''] Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company. |

||

| Line 148: | Line 130: | ||

* Foucart, Claude (1978). ''L'Aspect Méconnu d'un Grand Lutteur.'' Atelier National de Reproduction des Thèses, Université de Lille III. |

* Foucart, Claude (1978). ''L'Aspect Méconnu d'un Grand Lutteur.'' Atelier National de Reproduction des Thèses, Université de Lille III. |

||

* Gough, Austin (1996). ''Paris et Rome. Les Catholiques Français et le Pape au XIXe Siècle.'' Paris: Éditions de l'Atelier. |

* Gough, Austin (1996). ''Paris et Rome. Les Catholiques Français et le Pape au XIXe Siècle.'' Paris: Éditions de l'Atelier. |

||

* Gurian |

* {{citation |last=Gurian |first=Waldemar |date=1951 |title=Louis Veuillot |journal=Catholic Historical Review |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=385–414}} {{JSTOR|25015203}} |

||

* Isser, Natalie (1979). "The Mortara Affair and Louis Veuillot," ''Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History'' '''7''', pp. 69–78. |

* Isser, Natalie (1979). "The Mortara Affair and Louis Veuillot," ''Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History'' '''7''', pp. 69–78. |

||

* Laurioz, Pierre-Yves (2005). ''Louis Veuillot: Soldat de Dieu.'' Éd. de Paris, 2005. |

* Laurioz, Pierre-Yves (2005). ''Louis Veuillot: Soldat de Dieu.'' Éd. de Paris, 2005. |

||

* Le Roux, Benoît (1984). ''Louis Veuillot: Un Homme, un Combat.'' Paris: |

* Le Roux, Benoît (1984). ''Louis Veuillot: Un Homme, un Combat.'' Paris: Téqui, 1984. |

||

* [[James MacCaffrey|MacCaffrey, James]] (1905). [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast08unkngoog#page/n446/mode/2up "Louis Veuillot,"] ''The Irish Ecclesiastical Record'' '''16''', pp. 430–441; [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast03unkngoog#page/n336/mode/2up Part II], [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast03unkngoog#page/n554/mode/2up Part III], ''The Irish Ecclesiastical Record'' '''17''', pp. 323–334, 541–555. |

* [[James MacCaffrey|MacCaffrey, James]] (1905). [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast08unkngoog#page/n446/mode/2up "Louis Veuillot,"] ''The Irish Ecclesiastical Record'' '''16''', pp. 430–441; [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast03unkngoog#page/n336/mode/2up Part II], [https://archive.org/stream/irishecclesiast03unkngoog#page/n554/mode/2up Part III], ''The Irish Ecclesiastical Record'' '''17''', pp. 323–334, 541–555. |

||

* [[James MacCaffrey|MacCaffrey, James]] (1910). [https://archive.org/stream/cu31924092366396#page/n259/mode/2up "The Church in France."] In: ''History of the Catholic Church in the Nineteenth Century''. M.H. Gill & Son, pp. 233–251. |

* [[James MacCaffrey|MacCaffrey, James]] (1910). [https://archive.org/stream/cu31924092366396#page/n259/mode/2up "The Church in France."] In: ''History of the Catholic Church in the Nineteenth Century''. M.H. Gill & Son, pp. 233–251. |

||

* McMillan, James F. “Remaking Catholic Europe: Louis Veuillot and the Ultramontane Project.” Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 14, no. 1 (2001): 112–22. {{JSTOR|43100025}} |

|||

* Menczer, Béla (1962). [https://archive.org/stream/catholicpolitica00menc#page/192/mode/2up "Louis Veuillot."] In: ''Catholic Political Thought, 1789-1848''. University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 192–196. |

* Menczer, Béla (1962). [https://archive.org/stream/catholicpolitica00menc#page/192/mode/2up "Louis Veuillot."] In: ''Catholic Political Thought, 1789-1848''. University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 192–196. |

||

* [[Eugène de Mirecourt|Mirecourt, Eugène de]] (1856). ''Louis Veuillot''. Paris: Gustave Havard. |

* [[Eugène de Mirecourt|Mirecourt, Eugène de]] (1856). ''Louis Veuillot''. Paris: Gustave Havard. |

||

| Line 177: | Line 160: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

{{ |

{{wikiquote}} |

||

* Catholic Encyclopedia: [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15394b.htm Louis Veuillot] |

* Catholic Encyclopedia: [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15394b.htm Louis Veuillot] |

||

* Encyclopædia Britannica: [http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/627108/Louis-Veuillot Louis Veuillot] |

* Encyclopædia Britannica: [http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/627108/Louis-Veuillot Louis Veuillot] |

||

| Line 198: | Line 182: | ||

[[Category:Antisemitism in France]] |

[[Category:Antisemitism in France]] |

||

[[Category:Late modern Christian antisemitism]] |

[[Category:Late modern Christian antisemitism]] |

||

[[Category:French conspiracy theorists]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 13:32, 19 April 2024

Louis Veuillot | |

|---|---|

Veuillot, by Nadar, 1873 | |

| Born | 11 October 1813 Boynes, Loiret Department, France |

| Died | 7 March 1883 (aged 70) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Journalist, writer |

| Nationality | French |

| Spouse | Mathilde |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in France |

|---|

|

Louis Veuillot (11 October 1813 – 7 March 1883) was a French journalist and author who helped to popularize ultramontanism (a philosophy favoring Papal supremacy).

Career overview[edit]

Veuillot was born of humble parents in Boynes (Loiret). When he was five years of age, his parents relocated to Paris. With little education, he gained employment in a lawyer's office, and was sent in 1830 to serve with a newspaper of Rouen, and afterwards to Périgueux. Initially, Veuillot supported the July Monarchy of Louis Phillippe criticizing both Republicans and supporters of the deposed Bourbon Dynasty.[1]

He returned to Paris in 1837, and a year later visited Rome during Holy Week. There he embraced ultramontane sentiments, and became an ardent champion of Catholicism. The results of his conversion were published in Pélerinages en Suisse (1839), Rome et Lorette (1841) and other publications.[2] Veuillot's embrace of Ultramontanism led to his violent rejection of Bourgeois society and norms.[3] He had little regard for theological nuance and held fast to the overall philosophies of Joseph de Maistre and Louis de Bonald, the original Catholic counter-revolutionary thinkers.[4]

In 1840, Veuillot joined the staff of the newspaper Univers Religieux, a journal created in 1833 by Abbé Migne, and soon helped make it the leading organ of ultramontane propaganda as L'Univers. His methods of journalism, which made great use of irony and ad hominem criticism,[5] had already provoked more than one duel, and he was imprisoned for a brief time for his polemics against the University of Paris. In 1848, he became editor of the newspaper, which was suppressed in 1860,[6] but revived in 1867, when Veuillot resumed his ultramontane propaganda, causing a second suppression of his journal in 1874.[7] Veuillot then occupied himself by writing polemical pamphlets[8] against liberal Catholics, the Second French Empire and the Italian government. His services to the papal see were recognized by Pope Pius IX, on whom he wrote (1878) a monograph.[2] Matthew Arnold said of him:

M. Louis Veuillot is a polemic worthy of the golden age of polemics. He is singly devoted to ultramontanism; he lives on a small fixed salary from the proprietors of the Univers; he is a man of the purest and simplest domestic life; he is poor, and has a large family, but he has refused all offers of place and salary from the government, and maintains his entire independence.[9]

And Orestes Brownson wrote:

[Veuillot] manifests the temper and breeding of a fanatic, and seems to act on the principle that whoever differs on any important point in history, politics, or philosophy, from himself, must needs be a bad Catholic, or no Catholic at all. We question not his sincerity, we question not his personal piety; but we do question his qualification to be a Catholic leader. His mind is too narrow and one-sided for that, and his leadership, with the best intentions on his part, is fitted only to bring about the very results he most deprecates. Notwithstanding his hostility to those who regret the loss of parliamentary freedom, and his devotion to Imperialism, he has not been able to save his journal from an avertissement; and it would seem that, after having aided in erecting an Absolute government for his country, and in breaking down all the safeguards established by constitutionalism to freedom of thought, freedom of speech, and public discussion, the police have had the cruelty to take him at his word, and give him a taste of the despotism he has been willing to fasten upon others.[10]

Some of his papers were collected in Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires (12 vols., 1857–1875), and his Correspondance (7 vols., 1883–85) has great political interest. His younger brother, Eugène Veuillot, published (1901–1904) a comprehensive and valuable life, Louis Veuillot.

After the First Vatican Council, Veuillot's influence began to wane. In 1879 Pope Pius IX[clarification needed] released a letter praising him, but also regretting his "bitter zeal" in advocating his views. Among the lower clergy Veuillot retained influence. Politically he returned to advocating the restorations of the Bourbon Monarchy under Henri, Count of Chambord.[11]

Anti-Semitism[edit]

Veuillot was a virulent anti-Semite. As early as the 1840s, he wrote articles in L'Univers defaming Jews, portraying them as alien vagabonds, accusing them of blood libel, and asserting that the Talmud commanded Jews to hate all Christians.[12][13] He contemptuously dismissed Jews who criticized him as "the deicide people", claiming they were a foreign element which plotted to control all of French society.[14] Veuillot's hatred intensified during the Mortara case to the point where it put him at odds with Napoleon III whom he had previously supported, causing the latter to temporarily suppress the journal.[12] Veuillot's two-pronged assault on the Jews and liberalism would influence the anti-Semitism of Édouard Drumont, who worked for L'Univers in his youth.[15] Drumont, who in his turn was an employer of Charles Maurras, was admired by Karl Lueger, whom Adolf Hitler acknowledged as an influence in Mein Kampf.[16]

Legacy[edit]

A misattributed quote to Veuillot, "When I am weaker than you, I ask you for freedom because that is according to your principles; when I am stronger than you, I take away your freedom because that is according to my principles", is quoted in Frank Herbert's Children of Dune.

Works[edit]

- Correspondance, Tome II, Tome III, Tome IV, Tome V, Tome VII, Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1885.

- Rome et Lorette, J. Casterman, 1841.

- De l'Action des Laiques dans la Question Religieuse, Au Bureau de L'Univers, 1843.

- Vie de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ, Librairie Catholique de Périsse Frérés, 1864 [1st Pub. 1846].

- Les Libres-Penseurs, Jacques Lecoffre et Cie., 1850.

- La Légalité: Dialogue Philosophique, Plon Frères, 1852.

- Les Droits du Seigneur au Moyen Âge, L. Vivés, 1854.

- Le Parti Catholique, L. Vivés, 1856.

- Le Pape et la Diplomatie, Gaume Frères et J. Duprey, 1861.

- Waterloo, Gaume Frères et J. Duprey, 1861.

- Satires, Gaume Frérés et J. Duprey, 1863.

- Le Guêpier Italien, Victor Palmé, 1865.

- A Propos de la Guerre, Palmé, 1866.

- L'Illusion Libérale, Palmé, 1866.

- Les Odeurs de Paris, Palmé, 1867.

- Les Couleuvres, Victor Palmé, 1869.

- Corbin et d'Aubecourt, Victor Palmé, 1869.

- La Liberté du Concile, Victor Palmé, 1870.

- Paris Pendant les Deux Sièges, Victor Palmé, 1871.

- Le Parfum de Rome, Victor Palmé, 1871.

- Mélanges Religieux, Historiques et Littéraires, Tome II, Tome III, Tome IV, Tome V, Tome VI, L. Vivés, 1857–1875.

- Molière et Bourdaloue, Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1877.

- La Guerre et l'Homme de Guerre, Victor Palmé, 1878.

- Çá et Lá, Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1883.

- Historietes et Fantaisies, Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1883.

- Études sur Victor Hugo, Société Générale de Librairie Catholique, 1886.

Works in English translation[edit]

- In The Irish Monthly, Vol. 5, 1877.

- "The Graves of a Breton Household," pp. 417–418.

- "The Legend of the Red Lillies," pp. 756–757.

- The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ. New York: Peter F. Collier, 1878.

- Stephanie. Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son, 1883.

- "The Essence of Giboyer (A Retort to 'Giboyer's Son')." In: The Universal Anthology, Vol. XXVII. London: The Clarke Company, Ltd., 1899.

- In Béla Menczer (Ed.), Catholic Political Thought, 1789–1848, University of Notre Dame Press, 1962.

- "The True Freedom of Thought," pp. 196–205.

- The Liberal Illusion. Kansas City, Mo.: Angelus Press, 2005.

Gallery[edit]

-

Caricature of Louis Veuillot, by André Gil, from La Lune, 21 April 1867.

-

Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d.

-

Picture by Nadar, 1850s.

-

Portrait of Louis Veuillot, n.d.

-

"Masque pour Mardi-Gras." Caricature of Louis Veuillot, La Petite Lune, No. 37, 1878–1879.

-

"Pâquerette." Caricature of Louis Veuillot, La Petite Lune, No. 2, 1878–1879.

-

"Les Hommes D'Église." Caricature of Louis Veuillot, by Faustin Betbeder, 1870–1871.

-

Picture of Louis Veuillot, During the 1870s.

-

Pictures of Louis Veuillot, by Nadar, 1856.

-

"Les Deux Aveugles," (Vermorel and Veuillot), by Claude Guillaumin, La Rue, 26 October 1867.

-

Centennial Celebration of the Birth of Louis Veuillot, 5 October 1913.

-

Louis Veuillot Birthplace, in Boynes, Loiret, n.d.

-

Veuillot's Tombstone, Montparnasse Cemetery, n.d.

-

Veuillot, his two Daughters, Agnès and Marie, and his Sister, Élise, 1858.

-

Wife and Daughters of Louis Veuillot, n.d.

-

Monument in the Church of Voeu National, in Montmartre.

See also[edit]

- Charles Forbes René de Montalembert

- Henri, Count of Chambord

- Our Lady of La Salette

- Catholic Church in France

- Ultramontanism

- Pope Pius IX

Notes[edit]

- ^ Gurian 1951, p. 387.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Gurian 1951, p. 388–389.

- ^ Gurian 1951, p. 387–388.

- ^ "In Paris M. Louis Veuillot has given us another shameful specimen of Ultramontanism. Not satisfied with comparing savants to the phylloxera, he likens Protestantism to a loathsome disease whose name is usually confined to medical works." — "The Jesuits in France," The New York Times, August 16, 1875, p. 4.

- ^ "The Greater Excommunication, The Emperor and the Pope," The New York Times, April 20, 1860.

- ^ "The Clerical Press and Marshall Serrano," The New York Times, September 24, 1874.

- ^ "An impetuous, brutal journalist, whose verve and ardour came from Rabelais and Voltaire through Joseph de Maistre, Louis Veuillot was at the same time an exquisite writer and a violent Christian; he distributed holy water as though it were vitriol and handled the crucifix like a club." — Hanotaux, Gabriel (1905). Contemporary France. London: Archibald Constable & Co., p. 622.

- ^ Arnold, Matthew (1960). "England and the Italian Question." In: On the Classical Tradition, R. H. Super (Ed.), University of Michigan Press, p. 89.

- ^ Greene, Benjamin H. (1857). Brownson's Quarterly Review, Volume 2. New York: E. Dunigan and Brother. p. 398.

- ^ Gurian 1951, p. 407–408.

- ^ a b Levy, Richard S. (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 738.

- ^ Kaplan, Zvi Jonathan (2009). Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea?: French Jewry and the Problem of Church and State. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 65.

- ^ Michael, R. (2008). A History of Catholic Antisemitism: The Dark Side of the Church. Springer. p. 128.

- ^ Arnoulin 1902, p. 73–75.

- ^ Birnbaum 1993, p. 72.

References[edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Veuillot, Louis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ages, Arnold (1974). "Veuillot and the Talmud," Jewish Quarterly Review 64, pp. 229–260.

- Allison, John M.S. (1916). Church and State in the Reign of Louis Philippe. Princeton University Press.

- Arnoulin, Stéphane (1902), M. Edouard Drumont et les Jesuites, Paris: Librairie des Deux-Mondes

- Birnbaum, Pierre (1993), "Dreyfus avant Dreyfus : Drumont et la mise en scène de l'affaire", Mil neuf cent. Revue d'histoire intellectuelle, 11: 71–76

- Boureau, Alain (1998). "God's Party in the Great Combat." In: The Lord's First Night: The Myth of the Droit de Cuissage. University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, Marvin L., Jr. (1977). Louis Veuillot: French Ultramontane, Catholic Journalist and Layman, 1813–1883. Durham, N.C.: Moore Publishing Company.

- Cornut, Etienne (1891). Louis Veuillot. Paris: Victor Retaux et Fils.

- Corrigan, Raymond (1938). The Church in the Nineteenth Century. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company.

- Christophe, Lucien (1967). Louis Veuillot. Paris: Wesmael-Charlier.

- Dimier, Louis (1917). Les Maîtres de la Contre-Révolution au 19e Siècle. Paris: Nouvelle Librairie Nationale.

- Fernessole, Pierre (1923). Les Origines Littéraires de Louis Veuillot, 1813-1843. Paris: J. de Gigord.

- Foucart, Claude (1978). L'Aspect Méconnu d'un Grand Lutteur. Atelier National de Reproduction des Thèses, Université de Lille III.

- Gough, Austin (1996). Paris et Rome. Les Catholiques Français et le Pape au XIXe Siècle. Paris: Éditions de l'Atelier.

- Gurian, Waldemar (1951), "Louis Veuillot", Catholic Historical Review, 36 (4): 385–414 JSTOR 25015203

- Isser, Natalie (1979). "The Mortara Affair and Louis Veuillot," Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History 7, pp. 69–78.

- Laurioz, Pierre-Yves (2005). Louis Veuillot: Soldat de Dieu. Éd. de Paris, 2005.

- Le Roux, Benoît (1984). Louis Veuillot: Un Homme, un Combat. Paris: Téqui, 1984.

- MacCaffrey, James (1905). "Louis Veuillot," The Irish Ecclesiastical Record 16, pp. 430–441; Part II, Part III, The Irish Ecclesiastical Record 17, pp. 323–334, 541–555.

- MacCaffrey, James (1910). "The Church in France." In: History of the Catholic Church in the Nineteenth Century. M.H. Gill & Son, pp. 233–251.

- McMillan, James F. “Remaking Catholic Europe: Louis Veuillot and the Ultramontane Project.” Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 14, no. 1 (2001): 112–22. JSTOR 43100025

- Menczer, Béla (1962). "Louis Veuillot." In: Catholic Political Thought, 1789-1848. University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 192–196.

- Mirecourt, Eugène de (1856). Louis Veuillot. Paris: Gustave Havard.

- Murray, Eustace Clare Grenville (1873). "M. Louis Veuillot." In: Men of the Third Republic. London: Strahan & Co., pp. 188–201.

- Myers, Rev. E. (1903). "Louis Veuillot," The Catholic World 77, pp. 597–610.

- Neill, Thomas Patrick (1951). "Louis Veuillot." In: They Lived the Faith; Great Lay Leaders of Modern Times. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, pp. 299–324.

- Nielsen, Fredrik Kristian (1906). The History of the Papacy in the XIXth Century, Vol. 2. London: John Murray.

- O'Connor, R.F. (1879). "Louis Veuillot," Part II, The Monitor 1, pp. 333–346, 413–428.

- O'Connor, R.F. (1913). "Louis Veuillot," The American Catholic Quarterly Review 38, pp. 612–627.

- Parsons, Reuben (1901). "Louis Veuillot." In: Studies in Church History. New York: F.R. Pustet & Co., pp. 427–440.

- Pierrard, Pierre (1998). Louis Veuillot. Paris: Éditions Beauchesne.

- Preuss, Arthur (1914). "The Veuillot Centenary," The Fortnightly Review 21, pp. 3–4.

- Preuss, Arthur (1902). "A Fighting Editor," Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, The Review 9, pp. 535–537, 546–548, 564–567, 582–585, 598–601, 616–618.

- Sainte-Beuve, C.A. (1885). "Veuillot as Journalist." In: Causeries du lundi. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 86–90.

- Soltau, Roger Henry (1959). "Veuillot and L'Univers." In: French Political Thought in the 19th Century. New York: Russell & Russell, pp. 176–188.

- Sparrow-Simpson, W.J. (1918). "Louis Veuillot." In: French Catholics in the Nineteenth Century. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, pp. 107–121.

- Spencer, Philip (1954). Politics of Belief in Nineteenth-Century France: Lacordaire, Michon, Veuillot. London: Faber and Faber.

- Tavernier, Eugène (1913). Louis Veuillot; l'Homme, le Lutteur, l'Écrivain. Paris: Plon.

- Teeling, T.T. (1905). "Louis Veuillot and L'Univers," Part II, The Dolphin 8, pp. 546–558, 693–706.

- Veuillot, Eugène (1904). Louis Veuillot, Tome II, Tome III. Paris: Victor Retaux.

External links[edit]

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Louis Veuillot

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Louis Veuillot

- Dr. John C. Rao: Louis Veuillot – Icon and Iconoclast

- 1813 births

- 1883 deaths

- People from Loiret

- French newspaper editors

- French Roman Catholics

- Roman Catholic conspiracy theorists

- Our Lady of La Salette

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- 19th-century French journalists

- French male journalists

- French male writers

- Antisemitism in France

- Late modern Christian antisemitism

- French conspiracy theorists