Agnes of Bohemia

Agnes of Bohemia (also Agnes of Prague ; Czech Svatá (saint) Anežka Česká , also Anežka Přemyslovna ; * probably January 20, 1211 in Prague ; † March 6, 1282 there ) was a monastery founder and Bohemian princess, the youngest daughter of Ottokar I Přemysl and Constance of Hungary . She has been venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church since 1989 . From 1235 to 1237 she was abbess of the Agnes Monastery in Prague's old town .

Life

Youth and Marriage Policy

At the age of three, Agnes was given to the Cistercian monastery of Trebnitz in the Duchy of Silesia , where she was raised and cared for by her aunt, Hedwig von Andechs , who was later canonized . Because of the failed dynastic marriage plans of the Bohemian King in the Princely House of the Silesian Piasts , she then returned to Prague Castle . The princess spent her seventh and eighth years in the Premonstratensian monastery Doksany . Due to new marriage plans, this time to the Staufer imperial family, she sent Ottokar to the Viennese court of the Babenberger Leopold VI. , probably because she was supposed to acquire courtly etiquette as well as social manners and education there.

Leopold, however, thwarted the plans of the Bohemian ally by being able to position his own daughter as the wife of the young Henry (VII) . This was followed by further dynastic efforts to connect the Bohemian ruling family, which Agnes had as their subject: one documented by advanced negotiations in the English royal house, in this case on Henry III. directed, and a historically unsecured one that even speaks of the widowed Emperor Friedrich II as a courtship.

Entry to the monastery

In spite of these marriage plans, which from today's point of view were so unscrupulous as they always failed in the end, there is no doubt about Agnes' early developed, deep religious convictions; She preceded her decision as the bride of Christ , as sponsa Christi, to choose a spiritual path of life and to enforce it against other plans. Following the example of her cousin Elisabeth of Thuringia and Klaras , the companion of Francis of Assisi , with whom she was soon in correspondence, she decided to lead a religious life and to found several spiritual institutions, which made her one of the most important women in early history of the emerging Order of the Poor Clares and make one of the outstanding personalities of the Bohemian, even European history of the 13th century.

Probably soon after Elisabeth's death in 1230 and her brother Wenceslaus I assuming full power that same year , probably around 1232, she founded - with the strong support of the most important family members - initially a hospital for the poor in Prague's old town and, structurally, connected , an inclusive monastery . After numerous noble virgins had already entered the Damianite Convent in 1233 or 1234 , she herself took the veil in a solemn ceremony and in the presence of numerous Central European princes a year later. In the immediate vicinity of this step, she was invested in the office of abbess by the highly respected Franciscan provincial Johannes de Plano Carpini, as the Friars Minor, who arrived at the site at the latest in 1232, had introduced her to the ideas of a poor life in the imitation of Christ, which were presented in Clare and Francis of Assisi, but also in Elisabeth of Thuringia, had found their most ardent and best-known protagonists. Agnes' adherence to a life in absolute, that is, collective and individual poverty, rubbed against the plans of Pope Gregory IX. who was interested in the economic security of the monastery and hospital and who was by no means inclined to give his approval to every concern of the contemporary poverty movement. Even Agnes' submission of several of her own rules, which are likely to have been closely based on the way of life of Clare of Assisi, received no papal place - after all, Gregory gave her the privilege of not being able to be forced to accept property. Committed to the commandment of obedience and observance, the monastery head of royal descent finally agreed to the dissolution of the association of the two institutions consecrated to the seraphic saint from Assisi and resigned from the office of abbess in 1238. Afterwards she only meets us as soror maior , as an older sister, but she is likely to have had a considerable influence on the direction and guidance of the poor, trapped women, far beyond the title.

From the hospital community, the Brothers of the Cross with the Red Star, an autonomous canonical hospital order was gradually formed under papal directive, which, quickly separated from the women's monastery, finally received its own badge in 1251. The only order domiciled in Bohemia itself was richly endowed from the beginning and, at the height of its power in the 14th century, maintained numerous hospitals in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, there with a second, largely equal parenting house in Wroclaw . Following her example, Agnes' sister, Anna of Silesia , had developed a hospital community in the same direction as the seat of the Silesian Piasts and also founded a monastery for the female Franciscan branch. Like the older hospital orders, the Hospitallers or the Templars , the charitable element of the Bohemian friars visibly receded and gave way to a sovereignty and self-understanding of its leading brotherhood, that in the changed name of the Lords of the Cross , who have called themselves that at least since the early 14th century with the red star , finds an obvious expression.

In return for her defeats in terms of the legal foundations of the previous foundations, Agnes was able to have a Franciscan convent built in place of the detached hospital, which incidentally created the first Franciscan double monastery north of the Alps, which later underwent several architectural imitations in Central Europe should. From then on, the mendicants neighboring the women's monastery took on the pastoral duties, while the friars of Sankt Jakob, the oldest Franciscan accommodation in Prague, who settled near the Ungelthof, focused their local field of activity on the mainly German traders' settlement in which they were settled.

Worldly work

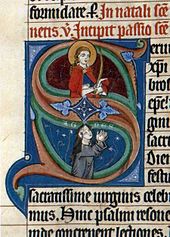

Despite the prescribed enclosure for her monastery, Agnes' influence on state politics remained considerable, even as a nun, which is not only due to her ongoing influence on the fate and expansion of the hospital community. In addition, she had a lasting effect on family decisions and tensions, for example, mediating a balance between her brother King Wenzel and his rebellious son Ottokar II. The monastery, in this case the place of the obvious second coronation of Wenceslas, was formed during the emerging foreign rule in the years of the so-called Brandenburg period, a refuge of Premyslid positions and resistance. Her nephew, Ottokar II., With the addition of the splendid, Gothic-style Chapel of the Redeemer to the existing monastery in the 1260s, also set an architectural example that pointed beyond Bohemia. The fact that the monastery complex "Zu Sankt Franziskus" within the sacred topography of Prague gained the status of an institution almost on par with the St. Vitus Cathedral was also due to the determination of the place as the burial place of the ruling Přemyslids, especially its female members, the preservation of several important relics and the production extremely splendid manuscripts in the scriptorium of the monastery complex.

Afterlife

Soon after her death on March 2, 1282, Agnes was venerated as a saint, but the civil war that began in the country after the defeat of Ottokar on Marchfeld in 1278, the foreign rule that prevailed during the even longer immaturity of the local successor Wenzel II, as well as the numerous violent famines and epidemics of the 1280s prevented influential forces from seeking the canonization of the princess at the right time. Corresponding attempts by the last Přemyslid Queen Elizabeth in 1328, in whose environment the writing of the oldest hagiography can be located in its central textual elements, were just as unsuccessful as an initiative of the same kind on the part of the order around 1339, in the closer context of which the traditional legend Candor lucis eterne ( Shine of eternal light ), or the request made by Charles IV in Rome in the mid-1350s.

Beatification and Canonization

The Hussite pre-Reformation, which led to the abandonment of the monastery complex by the members of the order, for a long time prevented any efforts in the direction of an approved adoration of the king's daughter. Nevertheless, her memory survived until the Baroque period, when the Jesuits and the Lords of the Cross with the Red Star dealt with her again. Jan František Beckovský wrote a biography in 1758. Agnes was beatified in 1874 , after counter-reformation and nationally minded forces tried for decades to raise knowledge about the royal Poor Clare and to discover her bones, which had not been found since the Hussite Wars.

During at least the latter should fail to the present day, she took Pope John Paul II. The canonization on 12 November 1989, a few days before the outbreak of the Velvet Revolution , in a solemn ceremony and the presence of thousands of Czech and Slovak pilgrims with the decree Salus Deo Nostro in the list of saints of the Roman Catholic Church .

reception

Several commemorative coins, the portrait on the 50 kroner note of the Czech Republic , which was founded in 1993 , the consecration of some churches, the celebration of their name day and the renaming of streets and hotels are testimony to a tender contemporary veneration of the princess, now as the Czech national saint . Not least because of the results of the Second World War and the Cold War, the fact that the Přemyslidine was worshiped in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period not only in Bohemia, but also in southern Germany and Silesia.

Despite some disappointments that the Catholic Church in the Czech Republic had to experience with regard to the restitution of its position in the post-communist country, the canonization at least helped the order of the Poor Clares, which has been so called since 1263, and the historiography facing the order, the extraordinary importance of Bohemia and was able to appreciate it more appropriately and thus build on levels of knowledge that have been lost since time.

literature

- Julius Glaubrecht: The blessed King's daughter Agnes of Bohemia and the last Premislids. Regensburg 1874.

- Klara Marie Faßbinder : The blessed Agnes of Prague. A royal clarissess . Leipzig 1960, St. Benno Verlag, 137 pp.

- Josef Beran : Blahoslavená Anežka Česka. (Blessed Agnes of Bohemia) (Sůl země vol. 7). Řim, 1974.

- Ivan Hlaváček : Agnes . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , column 213 f.

- Jaroslav Němec: Agnese di Boemia. La vita, il culto, la 'legenda'. (Ricerche francescane vol. 7) - Padova 1987.

- Jaroslav Němec: Adoration of the Blessed Agnes of Bohemia and the process of her canonization. Vienna 1989.

- Alfonso Marini: Agnese di Boemia. Con la collaborazione di Paola Ungarelli. (Biblio-theca Seraphico-Capuccina, vol. 38). Roma 1991.

- Vlastimir Kybal: Svatá Anežka Česká. Historický obraz ze 13. století. (Saint Agnes of Bohemia. A historical picture from the 13th century). (Pontes Pragenses vol. 8). Brno 2001.

- Kaspar Elm : Clare from Assisi and Agnes from Prague - Na Františku and San Damiano. In: Dieter R. Bauer, Helmut Feld and Ulrich Köpf (eds.): Franziskus von Assisi. The image of the saint from a new perspective. (Supplements to the archive for cultural history issue 54). Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2005, pp. 227–250.

- Frederik Felskau: Hoc est quod cupio. Approaching the Religious Goals of Clare of Assisi, Agnes of Bohemia, and Isabelle of France. In: Magistra. 12.2 (2006), pp. 1-28.

- Maria P. Alberzoni: Elisabeth of Thuringia, Clare of Assisi and Agnes of Bohemia. The Franciscan model of following Christ on this side and on the other side of the Alps. In: Elisabeth of Thuringia - a European saint. Articles, Petersberg 2007, pp. 47–56.

- Candor lucis eterne - shine of eternal light. The legend of St. Agnes of Bohemia. translated by Johannes Schneider, with an introduction by Christian-Frederik Felskau. (Johannes Duns Scotus Academy for Franciscan Intellectual History and Spirituality 25). B. Kühnen Verlag, Mönchengladbach 2007.

- Frederik Felskau: Agnes of Bohemia and the monastery complex of the Poor Clares and Franciscans in Prague. Life and institution, legend and veneration. 2 vols. Bautz Verlag, Nordhausen 2008.

- Frederik Felskau: Agnes of Bohemia. In: Stefan Samerski (Ed.): The state patron of the Bohemian countries. History - adoration - present. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2009, pp. 67–84.

- Církev, žena a společnost ve středověku. Sv. Anežka a její doba. (Church, woman and society in the Middle Ages. Saint Agnes and her time). Oftis, Ústí nad Orlicí 2010.

- Helena Soukupová: Anežský klášter v Praze. (The Agnes Monastery in Prague). 2nd Edition. Prague 2011.

- Svatá Anežka Česká - princezna a řeholnice. (Catalog for the exhibition of the same name). Praha 2011, ISBN 978-80-7422-145-3 .

- Helena Soukupová: Svatá Anežska Česká: Život a Legenda. Prague 2015.

Web links

- Agnes of Bohemia in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Literature by and about Agnes von Böhmen in the catalog of the German National Library

- Salus Deo nostro on vatican.va (Latin)

- FemBiografie Agnes von Böhmen with quotes, links and literature

- Rudolf Grulich : The Saint of the Velvet Revolution . Website kirche-in-not.de.

- St. Agnes of Bohemia - a contribution from Radio Prague

Individual evidence

- ^ Digitized version of the Moravian State Library

- ^ German National Library: Blessed Agnes of Prague

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Agnes of Bohemia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Anežka Přemyslovna, Anežka Česká |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | bohemian princess |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 20, 1211 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Prague |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 6, 1282 |

| Place of death | Prague |