Francis of Assisi

| Francis of Assisi | |

|---|---|

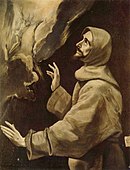

![The oldest painting, Francis of Assisi, from 1228, fresco in the Sacro Speco in Subiaco [1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/StFrancis_part.jpg/215px-StFrancis_part.jpg) The oldest painting of Francis of Assisi, from 1228, is a fresco in the Sacro Speco in Subiaco |

|

| Born | 1181 or 1182 ( Assisi in Italy) |

| Deceased | October 3, 1226 (The Portiuncula Chapel in front of Assisi) |

| canonization | July 16, 1228 by Gregory IX. |

| Holiday | October 4th (Catholic), October 3rd (Protestant) |

| Patron saint | Italy, animals, nature conservation |

| Attributes | With stigmata and seraph , preaching to the birds, with the wolf of Gubbio |

Francis of Assisi (also Francis of Assisi , Latin Franciscus de Assisio or Franciscus Assisiensis , born Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone ; * 1181 or 1182 in Assisi , Italy ; † October 3, 1226 in the Portiuncula chapel below the city) was the Founder of the Order of Friars Minor ( Ordo fratrum minorum , Franciscans ) and co-founder of the Poor Clares . He is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church .

Francis lived on the model of Jesus Christ (so-called imitatio Christi ). This way of life attracted like-minded companions, which led to the establishment of the Friars Minor, whose order grew rapidly. Despite great opposition during the first years of his work, he was canonized by the Catholic Church two years after his death . His memorial is in the Roman Catholic , the Old Catholic , the Anglican and some Protestant churches on October 4 , in the Evangelical Church in Germany the 3. October .

Life

youth

Francis of Assisi was born in 1181 or 1182 in the Umbrian city of Assisi at the foot of Mount Subasio . His parents were the wealthy cloth merchant Pietro di Bernardone and his wife Giovanna, known as Pica. Actually baptized Giovanni (German: Johannes), his father - who was on a trade trip in France at the time of his birth - gave him the nickname Francesco ("little French") after his return, a not far in time common but not unknown name.

Francis received a comparatively good education for a commoner, apparently because his father wanted him to be able to read, write and do arithmetic as a businessman. So he sent his son to the school of the parish of San Giorgio, which was maintained by the chapter of San Rufino. There Franz learned to read, write and some Latin at least. At the age of fourteen, Francis came of age accordingly and entered his father's company as a businessman. In this function he was quite successful and afforded himself to be generous with the acquisition. What his mother approved in this regard, made the tendentious portrayal of his hagiographs into a dissolute lifestyle of Francis, who kept his peers free at festivals with his father's money and who was thus often the focus of youthful celebrations.

Citizen and merchant

In November 1202 Francis went to war with Assisi against the neighboring city of Perugia , whereby Assisi was defeated (battle near Collestrada). Assisi belonged to the sphere of influence of the Hohenstaufen and Perugia to that of the Guelphs . Like other fighters from Assisi, he was imprisoned in Perugia and was only released in early 1204 after more than a year in exchange for a ransom from his father. His childhood dream of becoming a knight and his carefree life had been called into question by the war. When he was released, according to the first biography of Francis by Thomas von Celano, he was sick and deeply shaken.

When Walter III. von Brienne , a feudal man of the Pope, prepared a military campaign to Apulia in southern Italy in 1204 or 1205 in order to regain rule for the Pope against the Hohenstaufen, Francis set out with horse and armor to Apulia to join the knight who was loyal to the Pope , but turned back on the way there. The legends explained his repentance with the fact that Francis lay down slightly ill and had been called by God in a dream to place himself in the service of God instead of the service of a secular knight; so, according to the legend of the three companions , he dreamed that he had been addressed as follows:

- “Who can give you better? The master or the servant? "

- Franz replied: "The Lord!"

- Then the voice: "Why do you serve the servant instead of the master?"

- Franz: "What do you want me to do, sir?"

- The Lord: "Return to your home, because I want to fill your face in a spiritual way."

In the period that followed, Francis increasingly withdrew from his circle of friends and sought solitude. In 1205 or 1206 he went on a pilgrimage to Rome, on which, according to legend, he exchanged clothes with a beggar in order to "try out" life in total poverty. His behavior brought him into conflict with his father, who had big plans for his eldest son and who would not allow him to give away goods from his shop as alms.

vocation

During the prayer in San Damiano , around the summer of 1206, according to tradition, Christ's voice from the cross of San Damiano spoke to Francis - which first appeared with the legend of the three companions and was taken up by Celano in the second biography :

"Francis, go and rebuild my house, which, as you can see, is in complete decline."

In response to this vision, he begged building materials and, according to his biographers, began to restore the small Romanesque church himself. Later he renovated San Pietro della Spina in the same way, a church that no longer exists today, as well as the Santa Maria degli Angeli chapel, which is about three kilometers from Assisi and is known as Portiuncula .

Franz took goods and money from his parents' business for charity and for his structural restoration work on San Damiano. This led to a dispute with his father, who eventually led a trial against his son at the judgment seat of local bishop Guido II . In this court hearing, which took place in public on the cathedral square in the spring of 1207 , Francis undressed completely, with this gesture renounced his inheritance and renounced his father. His traditional statement:

“Until today I have called you my father on this earth; from now on I want to say: 'Father, who are you in heaven'. "

After that, Francis began to live as a hermit outside the city walls . He went from house to house begging for food. He referred to his voluntary poverty - alluding to ideas of chivalry and minstrelsong - as his "mistress". Francis often stayed in the small chapels around Assisi for prayer, especially in Portiuncula. According to his own statements, he cared for the lepers who had to live outside the city walls, which is also noted by his biographers. In his will he wrote:

“So the Lord gave me, Brother Francis, to begin the life of repentance: for when I was in sin, it felt very bitter to see lepers. And the Lord Himself brought me among them and I showed them mercy. And as I went away from them, what seemed bitter to me was turned into sweetness of soul and body. (Testament 1–3) "

In the biographies and legends this event is hagiographically exaggerated.

When Francis heard Mass one day in the small church of Portiuncula in 1208 , he became aware of the passage in the Gospel according to Matthew 10 : 5-14 EU which tells of the sending of the disciples :

The early sources report that Francis not only understood these words of the Gospels figuratively, but always tried to first apply them literally and directly. For him, the text was an invitation to live and work like the twelve disciples sent by Jesus, the apostles , namely to live in poverty and preach the gospel (also called apostolic life or Latin vita apostolica ). Based on the Gospel, Francis from now on dressed in a simple robe that was held in place with a rope, strictly refused possession and even contact with money and went barefoot whenever possible.

Francis saw himself as a penitent . As such, he exhorted those around him to love God and repent of their sins. Through these sermons and his extreme way of life, he met with ridicule and rejection from many people, but his example attracted many others, so that many brothers over time joined him.

Creation and confirmation of his order

According to tradition, Bernardo di Quintavalle , a wealthy nobleman from Assisi, and Pietro Catanii , a legal scholar, were the first to join Francis. The legend of the three companions reports that these three - Bernardo, Pietro and Francesco - consulted the Bible by opening it three times about the commission that God had for them (so-called Bible stabbing ). Her life program was the three words of Jesus found in this way:

According to his own statements, Francis did not intend to found an order. He writes in his will:

“And after the Lord gave me brothers, no one showed me what to do, but the Most High Himself revealed to me that I should live according to the prescription of the holy Gospel. (Testament 14) "

According to the biographies, the brothers initially stayed in a hut in Rivotorto , a few kilometers from Assisi, down on the plain, where they could not stay long. The sources give different reasons, namely either lack of space or the owner's own needs. In 1208 the abbot of the Benedictine abbey on Monte Subasio gave the little church Portiuncula to the brothers . Thomas von Celano narrates that Francis did not want any property and insisted that the brothers pay a kind of rent in the form of fish to the Benedictines. In the area around the church, the brothers lived in simple huts made of brushwood .

In the year 1209 Franz went to Rome with his first twelve companions - he or his biographer chose the number himself or his biographer deliberately to allude to the twelve apostles - to Rome to be met by Pope Innocent III. to seek confirmation of the way of life of their small community. This was not easy to achieve in the time of the Heretic Wars , because the establishment of new movements in the Curia was viewed with the utmost skepticism. The first version of the then presented in Rome Franciscan rule in the literature ( Regula primitiva or Urregel called) has been lost. It is believed to have been a concise and simple guide to living in poverty, composed of quotations from the Gospel .

From today's perspective, Franz defended his concerns skillfully by calling the brothers penitential or traveling preachers. The penitents and itinerant preachers were of the church as state recognized them whereas the remaining groupings of emerging in different places in the Middle Ages poverty movement , such as the Cathars / Albigensians , Waldensians , Humiliati or Brethren of the Free Spirit , at least later than heretical fought - and in particular had the Cathars wiped out by force of arms.

In the summer or autumn of 1210, the Pope gave the little community around Francis at least oral and presumably provisional permission to live in poverty and preach penance according to their rule. This was helped by the fact that Franz found advocates at the Curia, i.e. in the papal authorities, especially Cardinal Ugolino of Ostia . The legend of three companions mentions that Francis and his companions met the well-meaning Bishop of Assisi in Rome, who initiated a benevolent acceptance with the Pope through the Cardinal of Sabina (possibly Giovanni I. Colonna alias Giovanni the Elder ), whom he knew. However, the Cardinal of Sabina did not receive Franz and his companions without reservations, but only recommended their matter to the Pope after several days of questioning the founder of the order: He warned Franz that his rule of the order would lead to difficulties and urged him to prefer one of the to join existing orders.

The papal recognition of the order was probably only announced publicly before or during the IV Lateran Council in 1215 , because after this council the foundation of orders was based on a non- approved order rule (e.g. the rule of the Benedictines or the Augustinian canons ) prohibited. It is not known whether the recognition was in writing or still orally.

Further stations in life

In 1219, during the Damiette Crusade , Francis traveled as a missionary to Palestine , where he joined the crusader army that was on its way to Egypt. Near Damiette at the mouth of the Nile , he preached to Sultan Al-Kamil in the camp of the Muslim army . This incident is also documented in non-Franciscan sources, for example by the crusade chronicler Oliver von Paderborn . On this occasion he had three goals: firstly, he wanted to convert the sultan to Christianity, secondly, if necessary, to die as a martyr, and thirdly, to create peace. The Sultan gave Francis a bugle and was very impressed by the encounter with the mendicant monk, but Francis could not prevent the upcoming battle and the crusade as a whole continued.

Since this trip, his health has deteriorated increasingly, probably due to an eye infection that he had contracted in the Orient. There were also problems within the rapidly growing Order: while Francis was not in Italy, tensions rose in the Franciscan community, which was already represented throughout Europe. When Francis returned to Assisi in 1220, he transferred the leadership of the order to Petrus Catani . Around the same time, Pope Honorius III dictated. the brotherhood a clearly hierarchical, but hardly justice to the spirit of the founder of the order and also appointed the Cardinal of Ostia, Ugo dei Conti di Segni, the later Pope Gregory IX., as cardinal protector and corrector of the order. Thomas von Celano, the first biographer of Francis, describes the relationship between the protector and the founder of the order in a meaningful way: “St. Francis was attached to the cardinal [...] like the only child to his mother. He slept carelessly and rested on his loving bosom. The cardinal certainly took the place of the shepherd and performed his duties. But he left the name of the shepherd to the holy man ... “We can only speculate about the reasons and motives for these measures and the resignation of Francis. Presumably not all who had joined the Franciscan movement supported the strict demand of Francis that the Friars Minor should live without possessions. In addition, some of the Franciscans wanted their lives not to be based solely on the Gospel, but also to follow fixed rules of the order . The so-called "non-bulleted rule", which was created in 1221 and has a strong spiritual orientation, was considered impractical by many brothers. Obviously, Franz failed to keep the majority of his successors on the strict and principled course he wanted.

With the handing over of the leadership of the order, Francis withdrew internally from the community, according to the sources, from which he suffered greatly. In 1223 he reluctantly wrote a third, the last version of the Franciscan rule of the order in the hermitage of Fonte Colombo on the instructions of the Roman Curia . This rule was discussed at the Pentecost chapter - that was the name of the religious assembly - in June 1223, and that of Innocent III. following Pope Honorius III. approved the bullied rule with Solet annuere on November 29th of the same year.

Stigmatization

When Francis retired to Mount La Verna in the late summer of 1224 , where he had been using a small rock niche as a hermitage since 1212, a man hanging on the cross, who - like a seraph - had six wings, is said to have appeared to him first The legend of the three companions, written around 1246, shows that the seraph himself was crucified, which was prepared in the Legenda ad usum chori of Thomas von Celano, at least as a vision of Francis, written around 1230 . Reflecting on the interpretation of this phenomenon, according to the biographers, Francis himself saw wounds which they interpreted as imprinting the wounds of Christ. Bonaventure called the stigmata of Francis in his 1260-1262 - as historical evidence largely irrelevant - Legenda major that miracle "which shows the power of the cross of Jesus and reaffirms his fame". This is considered to be one of the first recorded cases of stigmatization . The day of this event is given in the three-companion legend of September 14, 1224, the day of the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross . The Franciscans and the Poor Clares celebrate this event as a festival of the stigmatization of St. Francis on September 17th.

The historicity of this stigmatization is not only disputed with regard to the time or place. So reports Elias of Assisi , an early associate of Francis, in his newsletter on the death of Francis, that it is not long before his death, the stigmata of Christ have received (non diu ante mortem ... apparuit) . Around half a dozen contemporary reports - such as those by Roger von Wendover - associate the stigmata with death or the time immediately before death. A connection with the stay on La Verna is not yet given and is only established by Thomas von Celano, who dates the stigmatization two years before the death of Francis. The question of whether the stigmata was a miracle and a special distinction for Francis was already controversial immediately after his death. Pope Gregory IX , who canonized Francis in 1228 without mentioning the stigmata, admitted looking back that he too had initially "secretly doubted the saint's side wound in his heart". When he is said to have seen the stigmatized in the dream, he changed his mind.

As part of an editorial-historical analysis of the various traditions, the journalist Paul Bösch points out that most of the doubters and opponents were Dominicans and secular priests . He attributes this to, among other things, competition among the mendicant orders or between religious and secular clergy . At the same time, a fundamental rejection of such emphasis on individual people, which culminated in an alignment with Jesus Christ, was widespread. Between 1237 and 1291 Gregory IX, but especially Alexander IV , Nicholas III. and Nicholas IV issued nine papal documents to affirm the Church's belief in the stigmatization of the saint. Alexander IV threatened deniers with impeachment and excommunication ; Church sentences were actually imposed in 1291 and 1361. Nonetheless, the stigmata have been interpreted as the result of a fall or illness. Martin Luther suspected that Francis taught it himself. This is followed by modern scientific interpretations, provided that they do not classify the accompanying miracle entirely as a legend like Karl Hampe , in that they judge the stigmata as the result of leprosy or other illnesses or - possibly in an ecstatic state - as self-taught.

Death and immediate aftermath

Since his stay in the Orient, Francis had gradually gone blind due to an eye disease, and moreover - presumably due to his fasting - stomach sickness and severely weakened. In the autumn of 1226 the Bishop of Assisi invited him to his palace. Two days before his death, however, Francis "hurried" out of the city to the Portiuncula Church. Celano interprets his motives in such a way that he wanted to die in his preferred place, where the movement of the brothers began. He probably also wished to be buried there. Celano narrates that the citizens of Assisi had his body carried to Assisi immediately after his death, as they feared that the citizens of neighboring and warring Perugia would seize his body. Because Francis was already considered a saint during his lifetime, the magistrate of the city of Assisi also expected political renown for the city and economic benefits, for example through pilgrimages, from his public veneration.

Tradition reports that Francis wished to be laid naked on the earth to show his loyalty to the “Mistress Poverty”. He was then dressed in a robe borrowed from a brother. At his request, the sun song he wrote was sung. Then he had the gospel of Jesus' suffering and death read to him. When he finally died, legend has it that larks were blown at an unusual time of day for them.

In the will that he left behind, Francis reaffirms what the content of his life plan was: his obedience to the Church, but that he came to live according to the Gospel even without any mediator, solely through a direct revelation from God, and that his absolute renunciation of any form of material and spiritual property is binding and must not be diminished by anyone. This will, according to his will, should be read out "to the end" at all future religious meetings without any change or interpretation in addition to the rule of the order.

canonization

Already on July 16, 1228, Pope Gregory IX was Francis . canonized . The oldest account of the festivities, however, seems more like a canonization of the Pope, while the concrete personality of poor brother Franz became a marginal note. The uncomfortable life plan of Francis was hardly mentioned in the report. So it is not surprising that this canonization was followed two years later by the papal bull Quo elongati , in which Gregory IX, the former protector of the life's work of Francis, denied the saint's testament that the order was legally binding. The burial corresponded to this: Francis was not buried in the Santa Maria degli Angeli in Portiuncula, rather his bones have been resting in a stone coffin in the burial chamber of the lower church of the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi since 1230 .

plant

Francis left behind many works of his own, although he called himself an idiota (in the sense of uneducated); this topos of modesty was common in the Middle Ages. Francis wrote his texts in old Italian or in awkward Latin, which he had a scribe corrected.

He left numerous prayers and chants ( laudi ), including the famous sun song . They are mainly songs of praise and worship texts. In the process, Francis, who emulated the knight ideal in his youth, was inspired by the Minnelied in song form and choice of words . In addition, Franz put together an office for the Liturgy of the Hours of his brothers from biblical quotations , in which he combined verses from the prophets (especially Isaiah) and the Psalms, but also from the New Testament, in free association. In addition to the hymns and prayers, letters have also been received from him, some of them only as drafts or dictations.

The only surviving autograph is the document for Brother Leo , which is kept in the Sacro Convento in Assisi. It contains the blessing for Brother Leo on the front and notes from the brother on the creation of this document on the back. According to tradition, Brother Leo kept this parchment sewn into his habit during his life .

It is very likely that Francis put together the various consecutive texts of the rules by himself . In addition to the lost original rule , he wrote the more detailed non-bulleted rule in 1221 and a little later the bulleted rule approved in 1223 . He also wrote down special instructions for the hermitages as well as further warnings and guidelines for the brothers and also for the sisters of St. Clare of Assisi .

In his spiritual will, which was written in Siena in spring 1226, Francis tried to remind his brothers of the original evangelical spirit. According to his will, it should be read out next to the order rule at all future religious meetings. Pope Gregory IX however, in 1230, two years after his canonization, denied him any legal obligation for the order with the Bull Quo elongati .

In intensive studies, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, Kajetan Eßer distinguished the real writings of Francis of Assisi from those only ascribed to him. The following is a list of the real writings that have now been recognized by research, with the title Eßer gave them:

| Prayer texts and meditations | Letters | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Rule texts and reminders to the brothers and sisters | Dictations and drafts | |

|

|

|

Early "biographies" and hagiography

With regard to the number of sources on life and work, Francis is one of the best-documented personalities of the Middle Ages. In the first century after his death, in addition to the writings he wrote himself, there were numerous portrayals of life, which, however, were mostly commissioned by church or order leaders. Accordingly, their purely hagiographic character is expressed in the draft of a certain image of St. Francis, which, for example, also reflects the changing self-portrait of the order. In addition to these official biographies, some non-official reports and traditions have been preserved that preserve memories from the immediate environment of Francis and provide important additional information about his character and life.

The interdependencies of the various traditions, their historical value and their trustworthiness are conceptually summarized as the “Franciscan question” in the ongoing research discussion on the life of the saint. Assessment and indexing of the early sources on the life of Francis are made more difficult by their own literary technique , which Helmut Feld called "hidden communication".

Thomas of Celano

The oldest surviving biography of Francis of Assisi was written by Thomas von Celano (1190–1260), who, according to his own statement, wrote down what he "heard from his own mouth and learned from credible and reliable witnesses". He wrote his first work ( vita prima , 1 Cel) on behalf of Pope Gregory IX. in the years 1228 to 1229. With the Legenda ad usum chori ("Legend for the choir use", 4 Cel) Celano probably created a short version of his first biography of Francis around 1230. It offered the most important information about the life of the saint in a compressed form, contained an exact date of his death and informed about the laying of the foundation stone of a new church of the Holy Sepulcher.

1246–1247 he wrote a second biography (2 Cel) - this time on behalf of the Franciscan Order. At the same time as the assignment for this new biography, “the call to the Friars Minor was issued to collect, write down and make available to Celano all of the Franz stories that had previously only been passed down orally.” Celano used the material that was then collected in his second biography. Finally, in 1250–1252, he wrote the "Treatise on the Miracles of St. Francis", a collection of miraculous stories ( Tractatus de miraculis S. Francisci , 3 Cel).

Companion tradition

Some of the material that Celano used in his second biography came from the legend of the Three Companions (Leg3Soc), which was probably created around 1246 - the dating is controversial . It received its name from an accompanying letter to the General Minister of the Order, Crescentius von Jesi († 1263), dated August 11, 1246, which has been passed down along with the legend. This letter was written by the three friars Leo of Assisi, Rufinus and Angelo and refers to the memories of Francis transmitted to the order.

Two smaller works - Intentio Regulae and Verba s - were directly associated with Leo of Assisi as the author . Francisci - which were written around the middle of the 13th century, although the question of authorship remains unanswered. Overall, they place themselves in the tradition of the companion legend.

The second official biographer of the saint was Bonaventure (1221-1274), born five years before the death of Francis , one of the most important scholars of his time, who was General Minister of the Order from 1257 and who was interested in a certain image of Francis. The disputes within the order about the correct poverty practice and the strictness of the order's rule should be resolved by a uniform and binding biography. That is why the General Chapter of the Franciscans, under the direction of Bonaventura in Paris in 1266, finally ordered the destruction of all previous Francis biographies. The absolute annihilation did not succeed, but the censorship was at least successful that the first biography of Francis of Celano appeared in print only in 1768, his second not until 1880. Bonaventure wrote the Legenda major 1260–1262. At the same time he wrote an abbreviated version, the Legenda minor , which was intended for reading in the choral prayer of the brothers. The Legenda uses all previous biographies as sources, plus a few eyewitness accounts from brothers. However, Bonaventure left out the special traditions of earlier legends. The verdict on Bonaventure's Francis biographies is partially devastating, as Adolf Holl calls them “highly smoothed” and finally judges in his Franz biography published in 1979: “The Bonaventure biography, the only officially approved for centuries, is historically worthless. Compared to the older sources, it brings little new material and suppresses pretty much everything that makes Franz interesting. "

Following Bonaventura, Bernhard de Bessa, after Helmut Feld, "Secretary of Bonaventuras", wrote Liber de laudibus beati Francisci . It is classified partly as a compilation , partly as a writ of edification. It may have been created after the General Chapter's call in 1276 to investigate the work of Francis, and it is therefore also given a programmatic aspect.

More legends

Further, partly independent, legendary representations of the life of Francis are the Legenda Perusina (also called Compilatio Assisiensis ) from around 1310 and the Speculum perfectionis from around 1318 and available in two different versions . Despite their late creation, both are certified to have a high degree of historical reliability.

The Legenda Perusina (LegPer) is less of a closed version of the legend than a compilation of early source material. The more extensive tradition of the Speculum perfectionis (SpecPerf) was classified by its first editor Paul Sabatier as the oldest Francis legend . A new edition, however, showed the influence of Ubertinus de Casale , a representative of the spiritual within the Franciscan order, which is why it is dated to the 14th century. In contrast, the Speculum perfectionis minus is of a pronounced compilatory character and draws mainly from the Legenda Perusina . While the speculum perfectionis according to subject matter, the first after his publisher missing Leonhard Lemmens also Speculum perfectionis Lemmens called Speculum perfectionis minus this gliedernde design. This could be an indication of its earlier origin, which Leonhard Lemmens already suspected. This smaller speculum perfectionis also has a programmatic character that is reflected above all in the detailed discussion of the poverty ideal.

The writing Sacrum commercium sancti Francisci cum domina Paupertate ("Covenant of St. Francis with the mistress of poverty") is indefinite . The dates here go from the year 1227, as some manuscripts - albeit belonging to the same family - pass on to beyond the end of the 13th century. The Sacrum Commercium , sometimes referred to as a mystery play , emphasizes the importance of real, and that means in the sense of the order of voluntary poverty, which should also serve to distinguish the order from the rest of the world.

The Actus beati Francisci et sociorum eius emerged around 1330/1340 . Hugolino von Montegiorgio is considered to be its author. Above all, it contains reports of miracles and visions, which are offered in individual episodes from the life of Francis and give the Actus a compilatory character. For the first time, Francis is addressed here as the old Christ . These Acts are of particular importance with regard to their influence on the Italian image of Francis, because they formed the basis for the Fioretti di San Francesco ("Little Flowers of St. Francis") - a translation made in the late 14th century, which is widespread in Italy however, does not strictly adhere to their specifications, but restructures episodes and omits some, but adds other things - like the comments on the stigmatization of Francis.

Around the beginning of the 14th century, the Actus beati Francisci in Valle Reatina was another compilation on the life of Francis. They were mainly devoted to the events that took place on the territory of the city of Rieti and included corresponding references. Apart from a few individual aspects, the Actus do not offer any information about the life of the saint that goes beyond older representations.

Around 1385-1390, Bartholomew of Pisa wrote his Liber de conformitate vitae beati Francisci ad vitam Domini nostri Jesu Christi ("On the uniformity of the life of Blessed Francis with the life of the Lord Jesus"). The title said it was program and was intended to propagate the uniqueness of Francis. In 1390 it was recognized by the General Chapter of the Order. As a result, at the latest with the emergence of reformatory efforts, this led to heated reactions. Luther wrote the foreword to a translation by Erasmus Alberus , in which it was titled Alcoran of the Friars Minor.

effect

The order founded by Francis spread throughout Europe within a few years, in the Holy Roman Empire as far as the Baltic Sea, where a branch was founded in Riga as early as 1230 . The cities in Central Europe, which expanded in the 13th century, were open to the immigration of poor but able-bodied people. The way of life of the new, papally recognized itinerant preachers without a claustrum, i.e. without a firmly delimited monastery district, obviously offered convincing social and spiritual solutions. The refusal of the Franciscans to seek possessions, power over others and social advancement were reasons for their widespread use and popularity, as well as their devotion to the poor and marginalized. According to the chronicler Jordan von Giano , they lived in Speyer “outside the walls with the lepers”. The Friars Minor represented an “alternative to the prevailing economy and society, indeed to the then prevailing mentality, culture and religiosity, based on the Gospel of Jesus Christ” and were therefore successful. It was an advantage that the Franciscans were supported in many places by the princes and city leaders and encouraged to found monasteries.

Over the centuries, numerous Franciscan orders have oriented themselves towards Francis and his spiritual companion Clare of Assisi . In general, many small religious communities emerged from the poverty movement of the Middle Ages, such as the Beguines (who were sometimes viewed with suspicion due to their supposed proximity to heretics and were later banned); Many of these communities joined the Franciscan Rule in order to evade a prohibition, because this corresponded best to their self-image. When new religious orders took on the growing social need in the 19th century, third orders such as the Ordo Franciscanus Saecularis ( Franciscan Community until 2012 ) became particularly important. With a total of tens of thousands of members, the Franciscan religious family is the largest religious movement in the Roman Catholic Church .

According to tradition, after 1223 in Greccio, Francis had the Christmas Gospel presented for the first time in the form of a living nativity scene. The fact that Holy Mass was celebrated in the presence of animals and in a stable cave over a real nativity scene shows Francis' sense of clarity and theatricality. As a modification of the mystery games widespread in the Middle Ages, this was an innovation that was adopted in a simplified form (for example through pictorial or figurative representations) in the devotional exercises of many monasteries. For centuries nativity scenes served the Franciscans as well as the Jesuits as illustrative material for catechesis . The custom of setting up a crib at Christmas has now spread all over the world.

The simplicity in the way of life and the brotherly relationship to creation, which Francis expressed in the Canticle of the Sun , justify his role model function in questions of the human-nature relationship to this day. Representatives of the ecological movement and critics of the anthropocentric orientation of Christian social teaching therefore saw in Francis the ideal type of an exemplary relationship between man and nature. The liberation theologian Leonardo Boff rated Francis as the “Western archetype of ecological man” in which the “sum of all ecological cardinal virtues” is realized. In 1979, Pope John Paul II appointed St. Francis as patron of environmental protection and ecology . In the Inter Sanctos proclamation document , the Pope referred to the great appreciation that Francis had for animate and inanimate nature and from which he perceived the moon and stars, fire, water, air and earth as "brothers and sisters". Pope Francis chose the opening words of the Canticle of the Sun by Francis of Assisi 2015 as the incipit of his encyclical Laudato si ' . As early as 1939, Francis was from Pope Pius XII. became the patron saint of Italy. At the same time, Francis is the patron saint of veterinarians. The city of San Francisco is named after him.

In early literature, Francis is often called Poverello ("the little poor man"). The biographies occasionally call him Seraphicus or Pater seraphicus (seraphic father); These epithets allude to the fact that, according to tradition, Franz saw a six-winged angel, a seraph , when he was stigmatized .

reception

While the early biographies (Thomas von Celano, Bonaventura), despite all the hagiographic exaggeration, still have a historical core to be emphasized , the later legends such as the Fioretti and the Legenda Perusina paint a very extreme image of Francis that is now perceived as kitsch. The widespread use of the Fioretti as a devotional book in the 19th and 20th centuries shaped the image of Francis among the population for a long time. In the last few decades, many authors have tried to convey a more moderate, more humane and less legendary picture of the person of Francis.

Visual arts

Francis often used the tau cross as a sign of blessing. He drew it on buildings, for example, and used it to sign his letters. The rope is therefore also used as a symbol of the Franciscan religious family. In the fine arts, Francis of Assisi is often depicted with a crucifix , a skull, pigeons sitting on him , a lamb or a wolf . This is intended to express his penance (crucifix, skull) or his peaceful and simple attitude of mind (dove, lamb).

The legends about the saint are also presented artistically. Giotto di Bondone's frescoes in the upper church of San Francesco in Assisi are the earliest examples depicting a cycle of events from his biography. Giotto draws on the biographies of Thomas von Celano and Bonaventura von Bagnoregio . His perspective representations and the role that architecture and landscape also play for the symbolic content of his pictures are remarkable. The legends are arranged in the church so that they have a theological reference to the scenes from the Old and New Testament depicted above . Significant examples of late medieval depictions of Francis north of the Alps can be found in the Staatsgalerie Füssen , St. Annen in Kamenz and in the Stralsund Museum .

- Artistic representations of Francis of Assisi in different centuries

Around 1400–1410: Stigmatization of St. Francis , by Gentile da Fabriano

Around 1502: Stigmatization of St. Francis , by Lucas Cranach the Elder

1520: Maria in Gloria with the Christ child and angels, Francis, Alvisus and founder Luigi Gozzi (kneeling), by Titian

1585: Stigmatization of St. Francis , by El Greco

1639: Penitent St. Francis , by Francisco de Zurbarán

1753: St. Francis in a triumphal chariot blesses his admirers, ceiling fresco by Franz Ludwig Hermann in the Franciscan Church in Überlingen

1978/1979: Franziskus , bronze statue by Martin Mayer near the art gallery in Mannheim

San Francesco d'Assisi , bronze statue at the Minorite Church in Vienna

music

According to the Fioretti , Francis went "singing and praising the great God". Of some of his songs, the music is not, but the text has survived: Franciscan composers of the Middle Ages stood out primarily with Laude compositions, such as Iacopone da Todi and Bianco da Siena . The creation of the Christmas carol in France and England was closely linked to the Franciscans: In the 18th century Giovanni Battista Martini , known as Padre Martini, became "the most celebrated of all Franciscan composers".

The following more recent works refer directly to Francis of Assisi or his texts:

- Franz Liszt : St. François d'Assise: La prédication aux oiseaux (1862–1863), the first of the Deux Legends for piano

- Franz Liszt: Cantico del sol di San Francesco d'Assisi (1862, revised 1880–1881) for baritone, male choir, orchestra and organ.

- Edgar Tinel : Oratorium Franciscus (op. 36, 1890).

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco : Fioretti di San Francesco (1919–1920) for voice and orchestra.

- Gian Francesco Malipiero : San Francesco d'Assisi (1920–1921), mystery play.

- Hermann Suter : a late Romantic oratorio Le Laudi di San Francesco d'Assisi , composed in 1923 and premiered in Basel in 1924.

- Paul Hindemith : Nobilissima Visione (1938), dance legend in 6 pictures; 1939 version for large orchestra. Scenario Paul Hindemith and Léonide Massine. World premiere: London, July 21, 1938, conductor: Paul Hindemith, choreography: Léonide Massine.

- Paul Hindemith: Nobilissima Visione. Orchestral suite based on the music of the dance legend (1938). World premiere: Venice, September 13, 1938, conductor: Paul Hindemith.

- Francis Poulenc : Quatre petites prières de Saint François d'Assise (1948) for male choir a cappella.

- Carl Orff : Sonnengesang des Sankt Franziskus (1954) for four-part women's or children's choir.

- William Walton : Cantico del sole (1973–1974) for a cappella choir.

- Olivier Messiaen : Saint François d'Assise . Scènes Franciscaines (1975–1983), Messiaen's only opera.

- Peter Janssens : Franz von Assisi , music game 1978 (text: Wilhelm Wilms)

- Thomas Fortmann : Oratorio francescano (1981–1982, revised version 2005) for soprano, baritone, choir and orchestra.

- Angelo Branduardi : La Lauda di Francesco (2000/2001), music, theater, dance with text and music for solo voice with the songs from the album L'infinitamente Piccolo .

- Hanno Haag : Franziskus (2001), oratorio for soprano, speaker, three-part choir, flute, horn, strings and percussion op.62.

- Dietrich Lohff : Franz von Assisi (2002), six scenes for speakers, soloists, choir and small orchestra.

- Ludger Stühlmeyer : Reise zu Franziskus (2006), Singspiel for children's choir, speakers and instruments.

- Ludger Stühlmeyer: Sound speech - Sonnengesang des Franziskus , for choir (SATB), violin and organ, premiere: Capella Mariana 2015 as part of the Days of New Church Music in Bavaria. Suae Sanctitati Papae Francisci dedicat.

- Carlo Pedini : Sei frammenti francescani (2006) for voice and orchestra based on texts by Thomas von Celano.

- Kurt Gäble , Paul Nagler : Franziskus - Das Musical (2007), for solo and choral singing, wind orchestra, cello, piano and vibraphone.

- Oliver Rosteck: Franz von Assisi - A Musical Way of Life for All Generations (2012), for flute, piano, solo part and 1-3 part choir.

- Bernfried Pröve : St. Francis legend for organ, premier April 21, 2013, St. Marien Church (Hof) .

- Peter Reulein (music) and Helmut Schlegel ( libretto ): Laudato si '- a Franciscan Magnificat (2016) oratorio for choir and orchestra

literature

In addition to non- fictional publications by researchers who try to develop the historical core of the legendary biographies from a scientific source criticism, there are also more recent fictional texts that interpret his life. The writers of the 20th century who published Francis novels include Felix Timmermans ( Francis , 1932), Dmitri Mereschkowski ( Francis of Assisi , 1938), Riccardo Bacchelli ( You are not my father anymore , 1956), Nikos Kazantzakis ( Mein Franz von Assisi , 1956), Luise Rinser ( Brother Fire , 1975) and Julien Green ( Brother Franz , 1983).

These novels deal very differently with the material given by the sources. Felix Timmerman's biography is strongly influenced by the sweetish, inner and romantically transfigured style of the legends, especially the Fioretti . Timmermans is primarily concerned with portraying the mysticism in the life of the saint. Luise Rinser, on the other hand, relocates the life story of Franz von Assisi to the present day. His community is seen by the middle-class contemporaries as a mixture of hippie movement, "gypsy pack" and esoteric sect. Rinser has the resulting conflicts recorded and commented on by a journalist. The author writes: “Since I portray Franz as if he were alive today, I have chosen a form that fits our time and the sober language of a skeptical newspaper reporter. All in all, I try to do something like what a pop musician does when he changes a Bach partita for our taste today: the partita remains, but it sounds different because new, electronic instruments are used and the rhythm is different . So you can say that I tried to make the story of Francis of Assisi pop. "

The budding Franciscan Siegfried Schneider was also heavily influenced in literary terms by the life and role model of Franz von Assisi - not least because of the motif of Greccio's crib. P. Schneider wrote, among other things, the festival of Ritter Franzens Brautfahrt. The mystical marriage of St. Francis of Assisi with Mistress Poverty (1921).

Movies

The life of Francis was also implemented several times as a feature film . The films are known:

- Francis, the juggler of God (Francesco, giullare di Dio) directed by Roberto Rossellini from 1951,

- Francis of Assisi Directed by Michael Curtiz from 1961,

- Brother Sun, Sister Moon directed by Franco Zeffirelli from 1972 ( Donovan adapted Francis' Canticle of the Sun for the movie's theme song ),

- Francis directed by Liliana Cavani from 1989 as well

- His name was Franziskus , a 2014 television two-part series, also directed by Liliana Cavani.

A documentary that should be mentioned is:

- Jesus of Assisi by Friedrich Klütsch

Political science

In 2008, the political scientists Ekkehart Krippendorff and Wolf-Dieter Narr as well as the sociologist Peter Kammerer addressed Franz von Assisi as “contemporaries for a different politics” and discussed the “political topicality of the life plan”. His life could be a regulative for today's time, not only in a religious sense, but also in a practical way for a secular humanism . Areas in which Francis could serve as a role model are the unity of theory and practice, respect for every life, material poverty versus the wealth of cultural creation as well as the formation of and participation in local and regional associations ("association" here in the sense from association, citizens' initiative).

Pope's name

On March 13, 2013, Jorge Mario Cardinal Bergoglio chose the name Francis after his election as Pope, based on Francis of Assisi . On October 4th 2013, the feast of St. Francis, Pope Francis visited Assisi with San Damiano and the tomb of the saint in the crypt under the Basilica of San Francesco , as well as the basilica in Santa Maria degli Angeli.

The trips of Pope Francis to the United Arab Emirates from February 3rd to 5th, 2019 and to Morocco on March 30th and 31st. March 2019 should honor the meeting of Francis of Assisi with the Sultan Al Kamil in 1219 and the 800-year presence of the Franciscan Order among Muslims.

Stamp

In memory of the encounter of St. Francis and the Sultan al-Kamil Muhammad al-Malik in 1219 which gave German Post AG with the initial issue an October 9, 2019 special stamp in the denomination out of 95 euro cents. The design comes from the graphic designer Greta Gröttrup from Hamburg . The stamp shows the embrace of Francis and the Sultan.

swell

- Enrico Menestò, Stefano Brufani (eds.): Fontes Franciscani. Edizioni Porziuncola, Assisi 1995.

- Aristide Cabassi (Ed.): Francesco d'Assisi. Scritti. Testo latino e traduzione italiana. Editrici Francescane, Padua 2002, ISBN 88-8135-007-6 (also contains the Laudes in Volgare).

- Dieter Berg , Leonhard Lehmann (ed.): Franziskus sources. The writings of St. Francis, biographies, chronicles and testimonies about him and his order . Kevelaer 2009.

- Kajetan Eßer: Opuscula Sancti Patris Francisci (Bibliotheca Franciscana Ascetica Medii Aevi XII) . Grottaferrata 1978

- Lothar Hardick OFM, Engelbert Grau OFM: The writings of St. Francis of Assisi . 10th edition. Kevelaer 2001, ISBN 3-7666-2069-X .

literature

Articles and monographs

- Dieter Berg : Poverty and Science. Contributions to the history of the study system of the mendicant orders in the 13th century . Schwann, Düsseldorf 1977.

- Paul Bösch : Franz von Assisi - new Christ: The story of a transfiguration . Patmos, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-72493-7 .

- James Cowan: Francis of Assisi: The Way of a God Loving One. Verlag Via Nova, Petersberg 2003, ISBN 3-936486-24-7 .

- Gunnar Decker : Francis of Assisi: The dream of the simple life . Siedler Verlag, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-8275-0061-8 .

- Helmut Feld : Francis of Assisi and his movement . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1994, ISBN 3-534-03087-7 .

- Friedrich Martin Fiederlein: Francis of Assisi. Its time, its life, its impact. In: Notepad No. 8 / May 1991 (Ed .: Bischöfliches Schulamt der Diocese Rottenburg-Stuttgart, Dept. I).

- Herbert Grundmann : Religious Movements in the Middle Ages. Studies on the historical connections between heresy, the mendicant orders and the religious women's movement in the 12th and 13th centuries and on the historical foundations of German mysticism . 4th edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1977.

- Emmanuel Jungclaussen : Following in the footsteps of Christ (vestigia Christi sequi). The spiritual path of Franz von Assisis. Auditorium, Schwarzach 1997, ISBN 3-8302-0581-3 . (Optionally on MC or CD)

- Gianfranco Malafarina: The Church of San Francesco in Assisi. Hirmer Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7774-3661-6 .

- Dirk Müller: Society and the individual around 1300 in vernacular Franciscan prose . Univ. Diss. Phil. University of Cologne 2003. PDF

- Jacques Le Goff : Francis of Assisi . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-608-94287-4 .

- Klaus Reblin: Francis of Assisi. The rebellious brother (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-60429-7 .

- Klaus Reblin: Friend and Foe - Francis of Assisi in the mirror of the Protestant history of theology . Göttingen 1988, ISBN 3-525-56530-5 .

- Oktavian Schmucki : The Stigmata of St. Francis of Assisi. A Critical Investigation in the Light of Thirteenth-Century Sources. Franciscan Institute, St. Bonaventure [NY] 1991.

- Matthäus Schneiderwirth (Ed.): The Third Order of St. Francis. Festschrift for the 700th anniversary of its foundation. On behalf of the Central Committee of the Third Order in Germany. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1921

- Christoph Stiegemann , Bernd Schmies, Heinz-Dieter Heimann (eds.): Franziskus. Light from Assisi. Hirmer Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7774-4081-1

- Hein Stufkens: The sevenfold path of Francis of Assisi . Aurum in Kamphausen Verlag, Bielefeld 2002, ISBN 3-89901-000-0 .

- André Vauchez : Francis of Assisi. History and memory. Verlag Aschendorf, Münster 2019, ISBN 978-3-4021-3244-9 (translation: Elisabeth Zacherl).

- Stephan Wyss: St. Francis of Assisi. Seeing things through , Edition Exodus. Lucerne 2000, ISBN 3-905577-39-9 .

- Stephan Wyss: The festival on Easter morning. From St. Francis of Assisi to François Rabelais , Edition Exodus. Lucerne 2005, ISBN 3-905577-60-7 .

- Manfred Zips: Francis of Assisi, vitae via. Contributions to the exploration of historical consciousness in the German Franciscan Vites of the Middle Ages with special consideration of the German-language works . Praesens, Vienna 2006, ISBN 978-3-7069-0114-7 .

Biographies

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Francis of Assisi. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 95-101.

- GK Chesterton : Thomas Aquinas / Francis of Assisi. First complete German text version. Nova & Vetera, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-936741-15-8 .

- Veit-Jakobus Dietrich: Francis of Assisi. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-499-50542-8 . (rororo monograph)

- Helmut Feld : Francis of Assisi. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44770-8 .

- Ivan Gobry: Francis of Assisi. Translated from the French by Oswalt von Nostitz . Rowohlt, Hamburg 1958

- Adolf Holl : The last Christian. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-421-01924-X .

Zurich, Rascher 1919. EOS-Verlag, Sankt Ottilien 1979, ISBN 3-88096-072-0 .

- Niklaus Kuster: Francis. Rebel and saint. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2009, ISBN 3-451-30153-9 .

- Niklaus Kuster: Franz and Klara of Assisi. A double biography. Matthias-Grünewald, Ostfildern 2011, ISBN 978-3-786-72801-6 .

- Volker Leppin : Francis of Assisi. Wbg Theiss, Darmstadt 2018, ISBN 978-3-80623817-4 .

- Raoul Manselli : Francis. The brother in solidarity. Benziger, Zurich et al. 1984, ISBN 3-545-20090-6 .

- Paul Sabatier : Life of St. Francis of Assisi. Nabu Press, La Vergne (Tennessee) 2010. (Original title: Vie de Saint François d'Assise. Translated by Margarete Lisco), ISBN 978-1-147-86392-5 (reprint, probably of the 1897 edition).

- Paul Sabatier, Frumentius Renner : Life of St. Francis of Assisi. Edited, abridged reprint of the edition

Web links

- Francis of Assisi - Life data PDF file

- Francis of Assisi in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Easily legible short biography ( memento of February 27, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) on the children's website of the Franciscan Minorites

- Literature by and about Franz von Assisi in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Franz von Assisi in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ^ On the inscribed dating to the 2nd year of the pontificate of Gregory IX. , so in the year 1228, already drew attention: Henry Thode : Francis of Assisi and the beginnings of the art of the Renaissance in Italy. Grote, Berlin 1885, p. 80 f. ( Digitized version ); so also Gerhart B. Ladner : The oldest picture of St. Francis of Assisi. A contribution to medieval portrait iconography. In: Peter Classen , Peter Scheibert (Hrsg.): Festschrift Percy Ernst Schramm dedicated to his seventieth birthday by students and friends. Volume 1. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 449-460 (reprinted in Gerhart B. Ladner: Images and Ideas in the Middle Ages. Selected studies in history and art. Volume 1. Edizioni de storia e letteratura, Rome 1983, p. 377-391); Helmut Feld : The iconoclasm of the West. Brill, Leiden 1990, p. 81; the same: Francis of Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 82; the fresco: Niklaus Kuster: The fresco of Frater Franciscus in Subiaco: Contrasting dates and interpretations in critical synopsis holds for the later reworking of a Benedict portrait from 1228 . In: Science and Wisdom. Vol. 62, 1999, pp. 49-77.

- ^ Michael Bihl: De nomine S. Francisci. In: Archivum Franciscanum Historicum. Volume 19, 1926, pp. 469-529.

- ^ Justin Lang: Franciscus v. Assisi . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 4 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 44–47, here col. 44 .

- ↑ On what is known about the education of Francis, see Nino Scivoletto: Problemi di lingua e di stile degli scritti latini di san Francesco. In: Francesco d'Assisi e francescanesimo dal 1216 al 1226, Atti del IV Convegno della Società internazionale di studi francescani (Assisi, 15-17 October 1976). Società internazionale di Studi francescani, Assisi 1977, pp. 101–124, esp. 108 note 8.

- ↑ Compare Achim Wesjohann: Mendikantische Gründungserzählungen in the 13th and 14th centuries. Myths as an element of institutional historiography of the medieval Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian hermits. LIT, Berlin 2012, p. 132; Augustine Thompson: Francis of Assisi. A New Biography. Cornell University Press, Ithaca / London 2012, p. 175 f.

- ↑ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi and his movement , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Darmstadt, 1994

- ↑ 1 Cel 3.2-5

- ↑ Leg3Soc 6.5-7.

- ↑ 2 Cel 10.

- ↑ Legend of three companions 20

- ↑ Testament 4, also in the "Greeting to the Virtues"

- ↑ Quoted from Franciscan Sources , Volume 1

- ↑ Testament, quoted from Franciscan Sources , Volume 1

- ↑ Paul Sabatier: Life of St. Francis of Assisi , p. 102 (see below biographies )

- ↑ a b Helmut Feld: Franziskus und seine Bewegungs , p. 302 ff.

- ↑ The text of the so-called "bulled rule" (Latin regula bullata )

- ↑ Leg3Soc 17.

- ↑ Thomas von Celano: Legenda ad usum chori 11.1: in visione Dei supra se vidit Seraphim crucifixum ( online ). On the spot see Chiara Frugoni : Francesco e l'invenzione delle Stimmate. Una storia per parole e immagini fino a Bonaventura e Giotto. Einaudi, Turin 1993, pp. 171-173.

- ↑ Adolf Holl : The last Christian. Francis of Assisi. DVA, Stuttgart 1979, p. 25.

- ↑ Bonaventure, Legenda major 3,1,1.

- ↑ So already Karl Hampe : The wounds of St. Francis of Assisi. In: Historical magazine . Volume 96, Issue 3, 1906, pp. 385-402, esp. 402 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ On circulars and Elias of Cortona as the author of the story of stigmatization, see Chiara Frugoni: Francesco e l'invenzione delle Stimmate. Una storia per parole e immagini fino a Bonaventura e Giotto. Einaudi, Turin 1993, pp. 51-104. On the question of the authenticity of the letter, see negative: Felice Accrocca : Un apocrifo la "Lettera enciclica" di frate Elia sul transito di S. Francesco. In: Collectanea Franciscana. Volume 65, 1995, pp. 473-509. Francesco Dolciami pleaded for authenticity: Francesco d'Assisi tra devozione, culto e liturgia. In: Collectanea Franciscana. Volume 71, 2001, pp. 5-45, here pp. 9-12.

- ↑ Roger von Wendover in the Chronica maiora of Matthaeus Parisiensis , dates the occurrence of the stigmata to the 15th day before the death of Francis ( digitized version ). See also Paul Bösch : Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, pp. 121–147, here p. 122, note 5 ( online ).

- ↑ Paul Bösch: Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, pp. 121-147, here pp. 124-132.

- ↑ Paul Bösch: Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, pp. 121-147, here p. 125. 126 f.

- ↑ Nelly Ficzel: The Pope as Antichrist. Church criticism and apocalyptic in the 13th and early 14th centuries (= Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions. Volume 214). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2919, p. 67.

- ↑ Paul Bösch: Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, pp. 121-147, here pp. 126. 138-141.

- ↑ Paul Bösch: Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, pp. 121–147, here p. 122, note 5.

- ↑ In the interpretation of Gal 6:17. Franciscans in Luther's time indicated this verse to the stigmata of St. Francis. “I believe that what you said about this matter was simply stupid and lying. Should it be that Francis wore wounds on his body, as he is depicted by the painters, then they were not impressed on him for Christ's sake, but he made them himself, out of a foolish monastic devotion or rather, for the sake of vain fame ... “Martin Luther: WA 40, 181., German version: The Letter to the Galatians , ed. by Hermann Kleinschmidt (= D. Martin Luther's interpretation of the epistle . Volume 4). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2nd edition Göttingen 1987, p. 357.

- ↑ Disputing historicity: Karl Hampe: Die wounds des hl. Francis of Assisi. In: Historical magazine. Volume 96, Issue 3, 1906, pp. 385-402; Paul Bösch: Between Orthodoxy and Heresy - An Interpretation of the Stigmata of Francis of Assisi. In: Journal for Religious Studies. Volume 17, 2009, p. 122.

- ↑ As a result of a leprosy disease: Joanne Schatzlein OSF, Daniel P. Sulmasy OFM: The Diagnosis of St. Francis: Evidence for Leprosy. In: Franciscan Studies. Volume 47, 1987, pp. 181-217, esp. 216 f. ( Abstract ); Chiara Frugoni: Francis of Assisi, the life story of a person. Translated from the Italian by Bettina Dürr. Benziger, Zurich / Düsseldorf 1997, pp. 137–167.

- ↑ Christoph Daxelmüller : "Sweet nails of the Passion" - The story of the self-crucifixion of Francis of Assisi until today. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, pp. 102-117; Richard C. Trexler: The Stigmatized Body of Francis of Assisi: Conceived, Processed, Disappeared. In: Klaus Schreiner , Marc Müntz (Hrsg.): Piety in the Middle Ages. Political-social contexts, visual practice, physical forms of expression. Fink, Munich 2002, pp. 463-497, esp. 483-488; Helmut Feld : Francis of Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 67; Otto Weiß : Stigmata: Signs of legitimation for holiness? In: Hubert Wolf (ed.): “True” and “false” holiness: mysticism, power and gender roles in 19th century Catholicism . Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, pp. 111–126, here p. 115 ( open access as PDF from De Gruyter).

- ^ I Celano 108

- ^ Jordan von Giano, Chronicle, 1262

- ↑ On the formation and stylization of inadequate education in Francis, see Oktavian Schmucki: Ignorans sum et idiota. The extent of St. Francis of Assisi. In: Isaac Vásquez (ed.): Studia historico-ecclesiastica. Festgabe for Luchesius G. Spätling, Pontificium Athenaeum Antonianum, Rome 1977, pp. 283-310.

- ↑ For his writing skills in Italian and Latin, see Attilio Bartoli Langeli : Gli scritti da Francesco. L'autografia di un illiteratus. In: Frate Francesco d'Assisi. Atti del XXI Convegno internazionale, Assisi, 14-16 October 1993. Centro italiano di studi sull'alto Medioevo, Spoleto 1994, pp 101-159.

- ^ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 9 f.

- ↑ An overview of the “Franciscan Question” offers: Franz Xaver Bischof : The “Franciscan Question” - an unsolved historiographical problem. In: Munich Theological Journal. Volume 41, 1990, pp. 355-382 ( PDF ); Franz Xaver Bishop: The State of the Franciscan Question. In: Dieter R. Bauer , Helmut Feld, Ulrich Köpf (eds.): Franziskus von Assisi. The image of the saint from a new perspective (= supplements to the archive for cultural history. Volume 54). Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar 2005, pp. 1–16.

- ↑ Helmut Feld: The technique of the "hidden communication" in the early Franciscan sources. In: Gennaro Luongo (ed.): Munera parva. Studi in onore di Boris Ulianich. Volume 1. Fridericiana Editrice Universitaria, Naples 1990, pp. 405-418; Helmut Feld: Francis of Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ 1 Cel Prologue; quoted from Leonard Holtz: Living differently with Francis. Johannes-Verlag, Leutesdorf 1981, ISBN 3-7794-0817-1 , p. 5.

- ^ Edition: Collegium S. Bonaventurae (ed.): Vita prima S. Francisci Assisiensis et eiusdem Legenda ad usum Chori. In: Analecta Franciscana. Volume 10, 1926, pp. 119-126; for a dating after 1253: Chiara Frugoni: Francesco e l'invenzione delle Stimmate. Una storia per parole e immagini fino a Bonaventura e Giotto. Einaudi, Turin 1993, pp. 171-173. 198 f. No. 167; for discussion dating around 1230: Timothy J. Johnson: Lost in Sacred Space. Textual Hermeneutics, Liturgical Worship, and Celano’s Legenda ad usum chori. In: Franciscan Studies. Volume 59, 2001, pp. 109-131, here p. 126 f.

- ^ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Editions: Leonhard Lemmens : Scripta fratris Leonis socii SP Francisci. Collegium S. Bonaventurae, Quaracchi 1901, pp. 82-99 (Intentio) , pp. 100-106 (Verba) ; Edith Paztor Il manoscritto Isidoriano 1/73 e gli scritti leonini su S. Francesco. In: Cultura e società nell'Italia medievale. Studi per Paolo Brezzi. Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo, Rome 1988, pp. 635-663, pp. 655-661 (Intentio) , pp. 661-663 (Verba) .

- ↑ For both writings see also Achim Wesjohann: Mendikantische Gründungserzählungen im 13th and 14th centuries. Myths as an element of institutional historiography of the medieval Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian hermits. LIT, Berlin 2012, pp. 92-97.

- ↑ Adolf Holl : The last Christian. Francis of Assisi. DVA, Stuttgart 1979, p. 22.

- ↑ Adolf Holl: The last Christian. Francis of Assisi. DVA, Stuttgart 1979, p. 25

- ↑ Helmut Feld: Francis of Assisi and his movement. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1994, p. 44

- ^ Edition: Collegium S. Bonaventurae (Ed.): Legenda vel vita S. Francisci a fr. Bernardo de Bessa conscripta. In: Analecta Franciscana. Volume 3, 1897, pp. 666-692; now in Enrico Menestò, Stefano Brufani (ed.): Fontes Franciscani. Edizioni Porziuncola, Assisi 1995, pp. 1253-1296.

- ^ Sophronius Clasen : Legenda antiqua S. Francisci: Investigation of the post-Bonaventurian sources of Francis, Legenda trium sociorum, Speculum perfectionis, Actus B. Francisci et sociorum eius and related literature. Brill, Leiden 1967, p. 383.

- ^ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 10.

- ↑ Edition: Marino Bigaroni (Ed.): "Compilatio Assisiensis" dagli scritti di fra. Leone e compagni su S. Francesco d'Assisi. Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1975.

- ↑ For the classification of the Legenda Perusina, see Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi and his movement. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1994, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Paul Sabatier (Ed.): Speculum perfectionis seu Legenda antiquissima sancti Francisci Assisiensis auctore fratre Leone. Fischbacher, Paris 1898 ( digitized version ); New edition: Daniele Solvi (ed.): Anonimo della Porziuncola, Speculum perfectionis status fratris minoris. Edizione critica e studio storico-letterario. SISMEL edizioni del Galluzzo, Florence 2006

- ^ Daniele Solvi (ed.): Anonimo della Porziuncola, Speculum perfectionis status fratris minoris. Edizione critica e studio storico-letterario. SISMEL edizioni del Galluzzo, Florence 2006, pp. XXIX – XXXIX

- ↑ Edition: Marino Bigaroni (Ed.): Speculum perfectionis (minus). Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1983.

- ^ Leonhard Lemmens (Ed.): Documenta antiqua Franciscana. Pars 2: Speculum perfectionis (Redactio I). Collegium S. Bonaventurae, Quaracchi 1901, pp. 23-84.

- ^ Leonhard Lemmens (Ed.): Documenta antiqua Franciscana. Pars 2: Speculum perfectionis (Redactio I). Collegium S. Bonaventurae, Quaracchi 1901, pp. 7-22.

- ↑ On this Sophronius Clasen: Legenda antiqua S. Francisci: Investigation of the post-Bonaventurian sources of Francis, Legenda trium sociorum, Speculum perfectionis, Actus B. Francisci et sociorum eius and related literature. Brill, Leiden 1967, p. 373 f .; see also Massimiliano Zanot: Lo speculum Lemmens: fonte francescana. Franciscanum, Rome 1996.

- ↑ Edition: Stefano Brufani (Ed.): Sacrum commercium sancti Francisci cum domina Paupertate. Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1990.

- ↑ For discussion see Stefano Brufani: Ideologia della povertà ovvero povertà dell'ideologia. In: Stefano Brufani (Ed.): Sacrum commercium sancti Francisci cum domina Paupertate. Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1990, pp. 3-55, esp. 3-18.

- ↑ See for example Engelbert Grau : The "Sacrum commercium sancti Francisci cum domina paupertate". In: Kurt Ruh (ed.): Western mysticism in the Middle Ages. Symposium Engelberg Monastery (= German symposia. Volume 7 of reports ). 1984 Metzler, Stuttgart 1986, pp. 269-285, here p. 275.

- ^ David Ethelbert Flood: The domestication of the Franciscan movement. In: Franciscan Studies. Volume 60, 1978, pp. 311-327, here pp. 325-327.

- ↑ Edition: Marino Bigaroni, Giovanni Boccali (ed.): Actus beati Francisci et Sociorum eius. Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1988.

- ^ Helmut Feld: Franziskus von Assisi. 2nd, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Achim Wesjohann: Mendikantische founding narratives in the 13th and 14th centuries. Myths as an element of institutional historiography of the medieval Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian hermits. LIT, Berlin 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Sophronius Clasen: Legenda antiqua S. Francisci: Investigation of the post-Bonaventurian sources of Francis, Legenda trium sociorum, Speculum perfectionis, Actus B. Francisci et sociorum eius and related literature. Brill, Leiden 1967, pp. 178-182. 201-207.

- ↑ Edition: Attilio Cadderi (Ed.): Anonimo Reatino, Actus Beati Francisci in Valle Reatina. Edizioni Porziuncola, S. Maria degli Angeli 1999; on dating ibid p. 62 f.

- ↑ Helmut Feld: Francis of Assisi and his movement. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1994, p. 49.

- ^ Edition: Collegium S. Bonaventurae (Ed.): Liber de conformitate vitae beati Francisci ad vitam Domini nostri Jesu Christi. In: Analecta Franciscana. Volumes 4 and 5, 1906-1912 ( online ).

- ^ Sophronius Clasen: Legenda antiqua S. Francisci: Investigation of the post-Bonaventurian sources of Francis, Legenda trium sociorum, Speculum perfectionis, Actus B. Francisci et sociorum eius and related literature. Brill, Leiden 1967, p. 392.

- ↑ Erasmus Alberus: The barefooted Münche Eulenspiegel and Alcoran. Wittenberg 1542 ( digitized version ), see Achim Wesjohann: Mendikantische Gründungserzählungen in the 13th and 14th centuries. Myths as an element of institutional historiography of the medieval Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian hermits. LIT, Berlin 2012, p. 125.

-

↑ Bavarian Franciscan Province (Ed.): 1625 - 2010. The Bavarian Franciscan Province. From its beginnings until today. Furth 2010, p. 6f.

Dieter Berg (Ed.): Traces of Franciscan History. Werl 1999, p. 19.

Bernd Schmies: Structure and organization of the Saxon Franciscan Province and its Custody of Thuringia from the beginning to the Reformation. In: Thomas T. Müller, Bernd Schmies, Christian Loefke (Eds.): For God and the World. Franciscans in Thuringia. Paderborn u. a. 2008, pp. 38–49, here p. 39ff. - ↑ Johannes Schlageter : The beginnings of the Franciscans in Thuringia. In: Thomas T. Müller, Bernd Schmies, Christian Loefke (Eds.): For God and the World. Franciscans in Thuringia. Paderborn u. a. 2008, pp. 32–37, here pp. 33f.36.

- ↑ Raynald Wagner: On the history of the Bavarian Franciscan Province from 1625 to 1802. In: Bayerische Franziskanerprovinz (Hrsg.): 1625 - 2010. The Bavarian Franciscan Province. From its beginnings until today. Furth 2010, pp. 6–29, here p. 7f.

- ↑ Lynn White, "Historical roots of our ecological crisis", in: Science 155 (1967), pp. 1203-1207. Also: Carl Amery "But when the salt has become stale ... Do the churches announce that they are up to date?", In: ders. (Ed.), Are the churches at the end? Regensburg (Pustet) 1995, ISBN 3-7917-1455-4 , pp. 9-20.

- ↑ Santmire, The Travail of Nature: The Ambiguous Ecological Promise of Christian Theology. Philadelphia (Fortress Press) 1985, ISBN 978-1-4514-0927-7 , pp. 106-119.

- ↑ Thorsten Philipp: Green zones of a learning community. Environmental protection as a place of action, activity and experience of the church. Munich (oekom Verlag) 2009, ISBN 978-3-86581-177-6 , pp. 79 and 98 f.

- ↑ Leonardo Boff: On the dignity of the earth. Ecology, politics, mysticism. Düsseldorf (Patmos) 1994, p. 57. ISBN 978-3-491-72308-5 .

- ↑ Inter Sanctos. Apostolic letter of Pope John Paul II (November 29, 1979), available at http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/apost_letters/1979/documents/hf_jp-ii_apl_19791129_inter-sanctos_lt.html

- ↑ Burkhard Kunkel: Sanzkower Franziskusretabel, cat.no.109 . In: Stiegemann, C., Schmies, B., Heimann, H.- D. (Eds.): Franziskus - Licht aus Assisi, Munich 2011 . Munich 2011, p. 330-331 .

- ^ Stanley Sadie (ed.): The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Macmillan Publishers, London 1980, keyword "Franciscan friars": "The Fioretti recount that St Francis himself went about 'cantando e laudando magnificamente Iddio'."

- ↑ Stanley Sadie (Ed.): The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians , Macmillan Publishers, London 1980, keyword "Franciscan friars": "... the most celebrated of all Franciscan musicians ..."

- ↑ Creating sound spaces for sacred music of our day. In: Die Tagespost , October 15, 2015, p. 10 Culture.

- ^ Gabriel Dessauer, Franz Fink, Andreas Großmann, Peter Reulein: Laudato si '- A Franciscan Oratorio - oratorio for choir, solos and orchestra . Ed .: Department of Church Music of the Diocese of Limburg . Limburg an der Lahn November 6, 2016 (text booklet for the premiere on November 6, 2016 in the High Cathedral of Limburg ).

- ↑ Pontifical Mass and Festival Concert - Church Music Department in the Diocese of Limburg celebrates its 50th birthday. Diocese of Limburg , October 25, 2016, archived from the original on November 6, 2016 ; accessed on November 6, 2016 .

- ↑ Luise Rinser: Brother fire. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-596-22124-2 . There at the end of the author's foreword on page 13

- ↑ See Association in the Wiktionary

- ^ Peter Kammerer, Ekkehart Krippendorff , Wolf-Dieter Narr : Franz von Assisi - Contemporary for Another Politics , Patmos, Düsseldorf 2008, ISBN 978-3-491-72520-1 , p. 169

- ^ Short biography of Radio Vatican ( Memento of July 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). Vatican Radio, March 13, 2013

- ^ FAZ: In the footsteps of the patron

- ^ Deutsche Welle

- ↑ vaticannews.va: Pope in Morocco: “Nice sign of appreciation for Francis of Assisi” , interview by Gudrun Sailer with brother Jürgen Neitzert OFM, March 27, 2019.

- ↑ Internet article on the special postage stamp from October 9, 2019 on vaticannews.va (German); last accessed on November 3, 2019.

- ↑ Special stamps October 2019 - Federal Ministry of Finance - Topics. Retrieved November 3, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Francis of Assisi |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Francis; Bernardone, Giovanni Battista (baptismal name); Poverello (widely used in literature); Pater seraphicus (nickname); Seraphicus (nickname) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder of the Catholic Order of Franciscans, Catholic saint, patron saint of Italy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1181 or 1182 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Assisi , Umbria, Italy |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 3, 1226 |

| Place of death | Portiuncula near Assisi, Umbria, Italy |