Jereruk

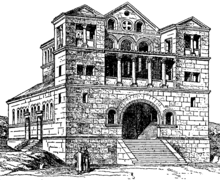

Jereruk ( Armenian Երերույքի ), also Yererouk, Yereruyk, Ererouk, Ereruk ', Jererujk and Jererukh , is a former church building of the Armenian Apostolic Church in the northern Armenian province of Shirak near the settlement of Anipemza directly on the Turkish border. The three-aisled basilica , built in the 5th or 6th century and later hardly changed, shows the clearest Syrian influence of all early Christian Armenian sacred buildings . It was badly damaged in an earthquake in the 17th century and partially restored except for the missing roof in the first half of the 20th century. The mighty ruin has been on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1995 as the most important Armenian basilica preserved from pre-Arab times .

In a grave from the 8th / 7th centuries Century BC In the vicinity of the church a Urartean belt plate made of bronze was found, the design of which resembles Scythian and Assyrian grave finds.

location

Coordinates: 40 ° 26 ′ 23 " N , 43 ° 36 ′ 33" E

Coming from Yerevan about 20 kilometers behind Etschmiadzin in Armavir, a country road (H17) branches off the M5 in a north-westerly direction and leads through a flat hilly area with some villages surrounded by small parceled fields parallel to the Turkish border to Anipemza. Alternatively, Anipemza can be reached via the M1 , which connects Yerevan directly with Gyumri . In Talin and Mastara, secondary roads branch off to the west from the M1.

The border river Achurjan , which flows into the Macaws , is dammed up north of the village to form a 20-kilometer-long artificial lake, which extends in the north to shortly before Gyumri and serves both countries for field irrigation. The Achurjan itself flows in a deep gorge and is unsuitable for irrigation. In prehistoric times, the entire Achurjan valley north of Anipemza was a large lake on the west side of the volcanic mountain Aragaz . The ridges formed by the mass of lava flowing down held the water back.

The place Anipemza (Ani Pemza, until 1938 Kzkule) is declared as a rural community ( hamaynkner ) and consists essentially of a few blocks of flats that are lined up along the thoroughfare. In the 2001 census, there were 349 official residents. For January 2012 the official statistics indicate 505 official inhabitants. During the Soviet period there was an industrial factory in Anipemza for processing pumice stone , which, together with the tuff stone factory of Artik, was one of the country's leading manufacturers of building materials. After the country gained independence in 1991, the factory was initially closed. The resulting unemployment, the lack of drinking water and suitable arable land have led to an exodus of the population from the peripheral area.

The basilica of Jereruk is visible from afar on a gently undulating treeless plain on the southern edge of the settlement. The distance from the church ruins to the river is a little over 300 meters, the distance to the railway line in the east is less. In 1958, during excavations 200 meters southeast, the remains of a stone dam from the 4th / 5th century came. Century emerged, with the water from a channel derived from Achurjan was stored in a basin. Nearby are the ruins of a medieval village, a not yet excavated chapel and a former cave. Eight kilometers to the northwest are the remains of the medieval Armenian capital Ani on the Turkish side on Achurjan. The first syllable of the name Anipemza consists of the memory of the most important Armenian ruins, which cannot be reached from here, and the addition -pemza, which is derived from the Russian word for pumice stone.

Urartian site

An Iron Age burial ground was discovered in a depression east of the basilica . From the 9th century BC The Urartians founded a number of fortified settlements on the slopes of the Aragaz and in the fertile Aras Valley, where they made the land arable through irrigation canals. The cities of Argishtichinili (Argištiḫinili) near Armavir, which was created by King Argišti I (ruled around 785-753), Dvin and Metsamor, have been well researched. The name Anipemza appears in the historical literature because here in grave 6 one of the numerous Urartian bronze and gold belts from the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Was found. None of these belt plates, embellished with delicate depictions of animals, were completely preserved in order to measure their original length, and the origin of most of them is unknown. The stylistically uniform bronze belts of Anipemza, Zakim (Turkish province of Kars ) and Gushchi (at the northern end of Lake Urmi ) show several rows of hallmarked animals that always move in one direction. The edges are perforated without any traces of rivets; the sheets were therefore probably sewn onto a fabric or leather pad.

No place of discovery of the belt plates can be clearly dated, with the exception of a copy from Altıntepe , where a cuneiform script indicates that its owner was a contemporary of Argišti I (r. 714–680). On the Anipemza belt, bird people can be seen, which are missing in Gushchi and resemble the winged centaurs of Altıntepe, with the difference that they do not hold bows in their hands like those. The motif of a tree of life formed from intertwined ribbons of the Anipemza belt can also be found on a golden pectoral (breast ornament), which is part of the Ziwiye treasure and (in addition to the Scythian and Assyrian ) confirms the Urartian influence on the local art production. From this it is concluded that the find objects could not have been the work of the Manneans who lived in Ziwiye. Furthermore, the tree of life motif of Anipemza is similar to those on short swords ( acinaces ) found in the Scythian Kurgan on the Kelermes River ( Krasnodar region , Russia).

Origin and dating of the church

In the 4th century BC Chr. Began in Great Armenia the rise of from Bactria derived Orontids , the first Armenian dynasty. From the 3rd century BC onwards, Armenia emerged from the Iranian-Asia Minor region. Chr. Hellenistic influenced. With the exception of the Roman temple of Garni , no buildings from the immediate pre-Christian period have survived, but on many early Christian church buildings multi-level plinth substructures ( Krepis ) indicate that the churches could have been built over an older pagan temple. Representatives of an early dating of the Jereruk basilica attest to its six-tiered substructure of pre-Christian origins, while the building type of the basilica dates back to the 2nd century BC. Roman secular buildings originating in BC follows.

According to the Armenian tradition, which becomes tangible in writing from the second half of the 5th century, St. Gregory built the first Christian church of the Armenians in Ashtishat shortly after 300 on the site of a destroyed Zoroastrian temple. The fact that the church building was erected in the same size above the temple only comes from a source from the 9th / 10th. Century. The Armenian art historian Toros Toramanian (1864–1934) claims such a direct sequence in his theory of evolution, according to which the Urartians developed long rectangular buildings and such pagan temples were converted into the first churches by installing an apse and side rooms in the east. Building studies on the masonry of the examples given by Toramanian could not confirm his thesis. The question is whether the tradition of sacred places of worship throughout antiquity, which was cultivated by different religions one after the other, can be used to infer the further use of building parts in individual cases.

The first Armenian places of worship were hall churches and basilicas derived from secular buildings , even before the central dome buildings characteristic of Armenian architecture were built. Josef Strzygowski saw it differently , who in his influential main work on Armenian architecture in 1918 placed the four-pillar central building allegedly from Iranian (literally “Aryan”) culture at the beginning and considered the Bagaran Cathedral as an essential stage of development. He considered the early Christian basilicas in Armenia to be a short-lived import from the Mediterranean region to which he attached little importance.

Five large basilicas have been preserved as ruins in Armenia from the pre-Arab period. In addition to Jereruk, these are Jeghward , Ashtarak and Aghtsk (between Agarak and Bjurakan ) in the south of Aragaz and Aparan (Kasagh) on the east side of the mountain. The first basilica of Dvin can only be reconstructed with uncertainty from the exposed foundations and wall remains. According to historical sources, the construction of Dvin is dated to the 460s with some probability, the approximate chronology of the other basilicas is only possible indirectly and through style comparisons. Aghtsk was probably the oldest basilica and was built around 364, because according to the "Epic Story" ( Buzandaran Patmut'iwnk ' ), written around 470 and attributed to an author named Faustus of Byzantium , in the mausoleum connected to the church that year a funeral took place.

The explorer and geologist Hermann von Abich (1806–1886) visited the place in 1844 and made a plan of the church that was first published in From Caucasian Countries: Travel Letters from 1859–1874 . Abich mistakenly added the remains of the wall to a cruciform church on his plan. Otherwise, interest in the basilica in the 19th century seemed to be low, presumably because European visitors perceived the central Armenian buildings as something special. This changed in the 20th century when the basilica of Jereruk became the most talked about early Christian church in Armenia due to its relatively good original state of preservation. Nikolai Marr uncovered the ruins in 1907 and published the first version of his results in Russian in 1910. In 1928 and 1948 the existing exterior walls were restored.

Nikolai Marr and with him Josef Strzygowski (1918) assumed it would have been made at the end of the 5th or beginning of the 6th century. Most Soviet researchers date the church to the 5th century. Jean-Michel Thierry and Patrick Donabédian believe that it was probably dated to the first half of the 6th century. The proponents of an emergence in the 4th / 5th Century recognize some alterations and additions in the 6th century. Thierry and Donabédien contradict this, for whom the construction seems to be based on a single plan. There is agreement, however, on the classification of the basilicas of Jeghward and Ashtarak in the 6th century.

The discussion about the dating includes the question of the origin of the basilical building type, which appears in Armenia at the earliest in the 4th century and after its heyday in the 6th century through cross- domed churches ( Tekor in the 5th century, Talin in the 7th century) and domed halls ( Ptghni in the 6th / 7th centuries). The gradual development and demarcation of the Armenian-Christian religious community is related to this question; a process that began with the official introduction of Christianity at the beginning of the 4th century and continued until around the 9th century. The two fundamental currents of faith were related, on the one hand, to the Hellenistic-Byzantine tradition, which was localized for the Armenians in terms of church politics in the Cappadocian Caesarea ( Kayseri ), and on the other hand in the older Syrian tradition, which started from Antioch . The center of the former was the northern Armenian Vagharschapat until the 5th century , the latter was Ashtischat in the southern Armenian canton of Taron. Until the introduction of the Armenian script at the beginning of the 5th century, Greek was used as the liturgical language in the north and Syriac in the south .

Of all the Armenian churches, the basilica of Jereruk shows the strongest Syrian influence in its floor plan and its sculptural design and stands for the connection between the Christian and architectural tradition originating from Syria. The close relationship between Jereruk and the early Christian Syrian churches, which were mainly in the area of the Dead Cities , was noticed first by Nikolai Marr. His thesis was largely adopted by research. The Armenian architectural historian Alexandr Sahinian (1910–1982) in the 1960s, who, with recourse to Toro's Toramanian Jereruk, declared a pagan temple rebuilt in the 4th century, and in 1984 Shahé Der Kevorkian (1944–1998), the Armenian, represent other views Churches dated earlier than the Syrian ones and thus precludes any influence. The Italian art historian Adriano Alpago Novello (1932–2005) considers Jereruk to be a largely independent creation in the 1980s, in which only Syrian forms of jewelry can be recognized. The details of this discussion include naming the Syrian churches that could be considered as role models and the controversial reconstruction of the collapsed roofing.

architecture

The long rectangular building made of light red tuff blocks stands on a six-step base. Four rectangular corner rooms tower over the basilica nave on the long sides and in the west. According to the floor plan shown by Strzygowski (p. 153), the total external length is 36 meters and the width of the prayer room without corner rooms is 14 meters outside. The walls are about 1.2 meters thick. The internal dimensions of the prayer room are given as 26.6 × 11.45 meters. On the two long sides and on the west side, the protruding corner rooms possibly delimited porticos . The two pilasters on the outside on the west side and the three pilasters on the outside on the long sides could have been assigned arcade supports on which the roof of the porticos rested. However, no column foundations were found on the long sides, which is why their existence remains speculative. Alternatively, these pilasters would only have served as wall divisions. In contrast, the arches of a later transverse buoy can be seen on the west side .

Three pillars with cruciform bases in each row divided the nave, as can be seen from observations by Nikolai Marr. As in the basilicas of Ashtarak and Aparan, the central nave was divided into four square fields, flanked by very narrow aisles, by the yoke arches between the pillars with a clear width of 6.1 meters. Pilasters can be seen on the inner walls, in line with which the pillars were arranged. Inside the straight east wall there is a horseshoe-shaped apse, the diameter of which is a little over five meters. The 7 × 2.6 meter side apse rooms are only accessible from the side aisles and are located across the east wall. Their barrel vaults also had upper floors covered with barrel vaults, which were separated and whose former entrances are unclear. The prayer room had no gallery, so the upper side apse rooms could only have been reached via the roofs of the side porticos. For the Syrian churches, the origin of the two-storey apse side rooms from the pagan temple construction is conceivable. They were also present at Basilica A (late 5th century) and Basilica B (early 6th century) in Resafa . The almost square corner rooms in the west can be entered from the side aisles and the portico on the west side. While the apse side rooms do not have their own apsidioles, they are present as eastern closures of the side porticos.

Two entrances are in the south wall and one entrance is in the west wall. This is the usual arrangement of Syrian basilicas, with the two south entrances allowing separate access for men and women. The north wall is windowless; A one-meter-wide window in each of the four wall fields on the south side and a three-arcade window with columns at the top of the west gable, which is flanked by arched windows at the height of the windows on the longitudinal walls, provide for light. The side windows of the west wall were partially covered in the lower area by the later added barrel vault of the portico. There is also a window in the apse and small window slits in the outer walls of the adjoining rooms.

The west facade with its dominant portal framed by the protruding corner rooms is unusual for Armenian churches and refers to Syrian models. The Armenian art historian Armen Khatchatrian (1971) compared the west facade with that of the Basilica of Deir Turmanin from the 5th century, which had already completely disappeared at the end of the 19th century and is only known from drawings from the 1860s, as well as the wide arcade basilica of Ruweiha (second half of the 5th century). Like the basilica of Qalb Loze (460s), it had a similar prestigious facade formed by a double tower .

The problem of roofing goes back to Josef Strzygowski's division of the three-aisled longitudinal structures. He distinguished the type of the "oriental" (i.e. Armenian) hall church with three longitudinal barrel vaults of almost the same height under a common gable roof, which he found mostly in early Christian Armenia, from the "Syrian-Asia Minor" (or "Hellenistic") basilicas with one high Obergaden (Lichtgaden) and a two-tier roof. In fact, three parallel barrel vaults under one roof are only characteristic of the late phase of Armenian architecture from the end of the 17th century and are mainly found in rural churches (for example Hripsime Church in Chndsoresk , Tandzaver , Jeghegis or Shativank , all around 1700). For Jereruk, Strzygowski reconstructed a triple barrel vault with a low arcade of light, which he saw derived from the "Syrian wooden roof basilica" and declared Jereruk to be the only "Hellenistic" basilica in Armenia. Instead of the wooden roof structure of the Syrian basilicas, following Nikolai Marr's view, he adopted brick vaults that would also have covered the porticos. Strzygowski's ideologically biased theory includes the claim that Armenian architecture inherited ancient Iran but had virtually no contact with Hellenism. Alexandr Sahinian took up the hypothesis of the “Armenian vaulted basilica” and from 1970 had the collapsed roof of the basilica of Aparan rebuilt accordingly.

Annegret Plontke-Lüning sees neither in the case of Aparan and Jereruk nor at all a sufficient certainty for such a reconstruction. She considers Jereruk to have adopted the type of the Syrian wide arcade basilica, which is characterized by wide yoke spacings and was covered overall by a two-tier wooden roof structure. Nikolaj Michajlovic Tokarskij (1961) takes a central position by proposing a wooden roof over the central nave and barrel-vaulted aisles. For Armen Khachatrian (1961), the central nave was covered with a wooden cantilever vault (Armenian Hazarash ), based on the model of the traditional Armenian house, with a smoke or light opening ( jerdik ) in the middle .

Building ornamentation

The portal porches on the south facade, supported on half-columns, are based on Greco-Roman models. A capital with a stylized, flat acanthus , the design of which is derived from Corinthian capitals, has been preserved on the eastern portal . The gable roofs above the portals with toothed cornices surround profiled horseshoe arches. The individual columns at the side of the entrances are also found in Awan Cathedral from the end of the 6th century. On the lintel above the western door there is a flat medallion of the cross, which is surrounded by two palm trees. The same combination on the eastern lintel is complemented by a medallion with a six-petalled flower on each side. The arched windows are framed by a horseshoe-shaped frieze that reaches down to the height of the portal gable and ends in short arms that curve outwards. This form, which originates from Syria, does not otherwise occur in Armenia. The west entrance is framed by a horseshoe-shaped wall arcade with a grooved profile that spans the columns. The capitals have stylized acanthus leaves. The lintel also contains a cross medallion in the center. On either side, an ibex looks towards the middle.

Inside, the triumphal arch and the cornice on the apse dome are decorated with a tooth-cut frieze. Cross medallions and rosettes are found on the capitals of the apse and one of the pilasters . Further remains of capitals with cross medallions are scattered between stones on the ground in the area.

Inscriptions and function

A Greek inscription, which has disappeared today, was on the south facade, which, according to Nikolai Marr's reading, contained the sentence: "The house ... is your sanctuary, oh Lord until the end of days." The inscription must have been written before the 7th century be because only at the Cathedral of Zvartnots still mid-7th century Greek characters instead appear generally introduced in the 5th century Armenian script.

An inscription to the left of the eastern portal of the south wall reads: “In the name of God in the year 487 I, the pious queen, daughter of Abas, wife of Šanhanšah Smbat and mother of Ašot, the inhabitants of Yereruyk for the eternal life of Smbat, des mighty Shahansah and ruler, freed. Anyone who opposes this document, from the nobility or from the common people, is condemned by the 318 patriarchs. ”The year 487 in the Armenian church calendar corresponds to 1038 AD.

An inscription on the eastern pilaster of the north wall provides an indication of the function of the church: “I, the priest Jacob, came from Kagaku-daşt through Christ to this place in the martyrdom of St. Prodromos for the intercession of the true believers; I renewed this martyrdom in the name of the Prodromos and first martyr. ”The eight-line text is dated to the 10th century. According to the priest Jacob, the church was dedicated to Johannes Prodromos (Greek "John the forerunner", John the Baptist as the forerunner of Christ). In pre-Arab times, the church was under the influence of the powerful Armenian Kamsarakan princes, who were descendants of the Armenian Arsacids . It could have been a remote pilgrimage center. This is supported by the architecturally accentuated west and south sides, which were common in Syrian pilgrimage churches, the previously unexposed wall remnants of the area, which are interpreted as a mausoleum, and the construction of the water basin.

literature

- Burchard Brentjes , Stepan Mnazakanjan, Nona Stepanjan: Art of the Middle Ages in Armenia. Union Verlag (VOB), Berlin 1981, pp. 60-62

- Paolo Cuneo: Architettura Armena dal quarto al diciannovesimo secolo. Volume 1. De Luca Editore, Rome 1988, pp. 234-237

- Annegret Plontke-Lüning: Early Christian architecture in the Caucasus. The development of Christian sacred buildings in Lazika, Iberia, Armenia, Albania and the border regions from the 4th to the 7th century (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Philosophical-Historical Class, Volume 359. Publications on Byzantium Research, Volume XIII) Verlag der Österreichische Academy of Sciences, Vienna 2007, enclosed CD-ROM: Catalog of preserved church buildings, pp. 367–372, ISBN 978-3700136828

- Christina Maranci: Medieval Armenian Architecture. Construction of Race and Nation . (Hebrew University Armenian Studies 2) Peeters, Leuven u. a. 2001, p

- Josef Strzygowski : The architecture of the Armenians and Europe. Volume 1. Kunstverlag Anton Schroll, Vienna 1918, pp. 153–158, 397–403, 442f ( online at Internet Archive )

- Patrick Donabédian: Documentation of the art places. In: Jean-Michel Thierry: Armenian Art. Herder, Freiburg / B. 1988, pp. 536f, ISBN 3-451-21141-6

Web links

- Ererouk . Armenian Studies Program

- Yereruyk Basilica . Armeniapedia

- Archival Photos by Nicholas Marr. Gateway ot Armenian Cultural Heritage

- Rick Ney: Shirak Marz. (PDF; 1.9 MB) TourArmenia Travel Guide, p. 23

Individual evidence

- ^ The basilica and archaeological site of Yererouk. UNESCO World Heritage Center

- ^ RA 2001 Population and Housing Census Results. (PDF; 932 kB) armstat.am

- ^ RA Shirak Marz. (PDF; 150 kB) armstat.am, p. 291

- ^ Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic. Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1979

- ↑ Mirjo Salvini: History and Culture of the Urartians . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, p. 129

- ↑ RW Hamilton: The Decorated Bronze Strip from Gushchi . In: Anatolian Studies 15, 1965, pp. 45-47, 49

- ↑ Helene J. Kantor: A Fragment of a gold appliqué from Ziwiye and Some Remarks on the Artistic Traditions of Armenia and Iran during the Early First Millennium B. C . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies , Vol. 19, No. 1, January 1960, pp. 1–14, here p. 7

- ^ Charles Burney, David M. Lang: The mountain peoples of the Middle East. Armenia and the Caucasus from prehistoric times to the Mongol storm. Kindler, Munich 1973, p. 342, ISBN 3-463-13690-2

- ↑ Sandro Salvatori: An Urartian Bronze Strip in a Private Collection. In: East and West , Vol. 26, No. 1/2, March – June 1976, pp. 97–109, here p. 109

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, p. 265 f.

- ↑ Christina Maranci, p. 117

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, enclosed CD-ROM: Catalog of the preserved church buildings, p. 14

- ^ Hermann von Abich, Volume 1, Vienna 1896, p. 201; after Josef Strzygowski, p. 158

- ↑ Christina Maranci, p. 28

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, enclosed CD-ROM: Catalog of the church buildings that have been preserved, p. 370

- ^ Josef Strzygowski, p. 154

- ↑ Jean-Michel Thierry, pp. 49f

- ↑ Nina G. Garsoïan: Janus: The formation of the Armenian Church from the IVth to the VIIth Century . In: Robert F. Taft (Ed.): The Formation of a Millennial Tradition: 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Witness (301-2001) . (Orientalia Christiana Analecta 271) Pontificio Instituto Orientale, Rome 2004, pp. 79–95, here p. 84

- ↑ Stepan Mnazakanjan: Architecture . In: Burchard Brentjes, pp. 58, 61

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, p. 63

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, p. 261 and accompanying CD-ROM: Catalog of Church Buildings that have been preserved, p. 370

- ↑ Natalia Teteriatnikov: Upper Story Chapels Near the Sanctuary, Churches of the Christian East. In: Dumbarton Oaks Papers , Vol. 42, 1988, pp. 65-72, here pp. 66f

- ↑ Melchior Comte de Vogüé: Syrie centrale. Architecture civile et religieuse du Ier au VIIe siècle. J. Baudry, Paris 1865-1877, Vol. 2, Plates 130, 132-136

- ↑ Christina Maranci, pp. 199f, 241

- ↑ Josef Strzygowski, pp. 144f

- ↑ Josef Strzygowski, p. 400

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, enclosed CD-ROM: Catalog of Church Buildings that have been preserved, p. 370f

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, p. 261

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, enclosed CD-ROM: Catalog of Church Buildings that have been preserved, p. 371

- ^ Patrick Donabédian: Documentation of the art places. In: Jean-Michel Thierry, p. 537

- ↑ Archival Photos by Nicholas Marr. (fifth figure)

- ↑ Translation by Annegret Plontke-Lüning (CD-ROM: Catalog of Church Buildings Remaining , p. 369) from Russian (Nikolai Marr: Ererujskaja bazilika. Moscow 1968)

- ↑ Kamsarakan. In: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Annegret Plontke-Lüning, p. 265