Expressive dance

As Ausdruckstanz refers to a form of artistic dance, wherein the individual and artistic representing (and in some cases processing) of feelings is an essential component. It emerged as a countermovement to classical ballet at the beginning of the 20th century .

Other names are modern dance and (especially in a historical context) free dance , expressionist dance or new artistic dance , in Anglo-American countries German dance .

Modern dance with the styles and forms of communication of the rhythmic and expressive dance movement was included in the German register of intangible cultural heritage in 2014 in accordance with the UNESCO Convention on the Preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage .

Disambiguation

The term “expressive dance” is a term used primarily today and retrospectively for a certain style of a certain era. The protagonists of this direction of artistic dance and the most famous publicists of the new dance art of the time such as Hans Brandenburg or Fritz Böhme did not use it themselves. According to Brandenburg, references to current art-historical style terms such as “ impressionistic ” and “ expressionistic dance” were “useless catchphrases” to distinguish between ballet and modern artistic dance. The term "expressive dance" is probably based on Rudolf Bode's book expressive gymnastics (1922). Bode referred to Ludwig Klages , whose work was expressive movement and creative power. Foundation of the science of expression was published in 1921 in an expanded edition. Genevieve Stebbins had already taught expressive gymnastics in the USA since 1885 , without using this term, on the basis of the system of expression by the French François Delsarte . The influence of Delsarte's teachings on prominent dancers such as Isadora Duncan , Rudolf von Laban or Ted Shawn has been described by them in their own publications.

Up to and including 1929, the term “modern art dance” was also used lexically without mentioning the term “expressive dance”. From 1930 to 1933 it found its way into various reference works (Junk: Handbuch des Tanzes ; Der Große Herder ; Beckmanns Sport Lexikon ), without mentioning little more than the contrast between the new dance art and classical ballet, which, incidentally, was already verifiable in the 18th century , for example with Marie Sallé . The problematic, fuzzy nature of the term led, for example, to the fact that the term “expressive dance” was officially defined in 1935 as an aspect of classical ballet, in whose avowed opposition modern dance actually emerged. The dying swan was named as an example of expressive dance . (The modern dance was instead referred to here as "The German dance form" as a distinction from the "classical dance form".)

The Dance Studies dates the beginning of expressive dance - after a previous generation with Loie Fuller and Isadora Duncan - by the appearance of Clotilde von Derp one hand and Mary Wigman and Rudolf von Laban other hand, to the period from 1910 to 1913. In the artistic work of the latter and their students as well A number of differently trained modern dancers of the time and their students are seen from today's perspective as the actual expressive dance. In addition, there is talk of an "expressive dance movement", a collective term which, in addition to this actual expressive dance, also includes "the comprehensive amateur dance and gymnastics movement that was in part closely related to Laban (less to Wigman)". However, not all persons and works of modern dance in Germany are in principle part of expressive dance. In particular, those who were more modern than expressive dance at that time, such as its antipodin Valeska Gert or the Triadic Ballet, cannot be assigned to expressive dance .

While the actual style, referred to primarily as expressive dance in retrospect, had already passed its peak around 1930 and lost its traces in the 1950s among the epigones , the term has found a continuation of use in dance education and dance therapy, especially since its translation from Laban's book Modern educational dance (1950) as The modern expression dance in education (1981).

history

Beginnings

In the beginning, ways were sought to find the natural movement of the body from the frozen, fixed forms . Much of these endeavors were taught under the label Delsarte System at the end of the 19th century .

The first famous representative was Isadora Duncan. She wanted to combine body, soul and spirit in her art and got her inspiration from the images on Greek vases and what she found in the works of Greek dramatists and philosophers in descriptions of ancient Greek dance. She was also the first dancer to write about her art and develop a dance theory.

In Germany, Clotilde von Derp was the first representative of “modern dance” in Munich from 1910 . Emil Jaques-Dalcroze founded his school for rhythmic gymnastics in Hellerau near Dresden. And many other free gymnastics styles and schools emerged.

A center for this back-to-nature movement was the Monte Verità artists' colony in the municipality of Ascona in Switzerland . Rudolf von Laban taught and worked there. He attempted to theoretically consolidate the movement theory of expressive dance and to develop a dance script for it. Since he later lived and worked in England, his influence in creative dance is strongest there, especially in the educational field in working with children.

With the social upheaval caused by the First World War , an outbreak of predetermined, outdated forms that no longer corresponded to the new attitude towards life took place in all the arts. The intense, dramatic expression of personal experience, exploding in colors, tones, words and movements, was the focus and became expressionism . Bizarre, weird, destructive forms were part of it, including the use of masks. In addition to known music, drums , xylophones and all kinds of rhythm instruments were used as accompanying music for expressive dance . There were even dances without music. Individual design, improvisation, individual dance were in the foreground.

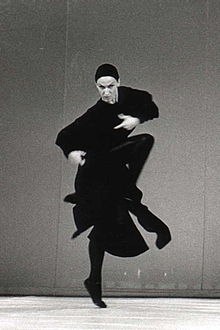

The expressive dance became known mainly through individual personalities; most sustained by Mary Wigman, her students Harald Kreutzberg and Gret Palucca and Dore Hoyer .

The women's movement also played a role in this development.

Weimar Republic

In the 1920s and 1930s, Dresden became the “Mecca” of this new dance art. Mary Wigman founded her dance school there in 1920, Gret Palucca in 1924. Dancers from all over the world came to study with them. The Japanese Ōno Kazuo saw Wigman, Kreutzberg and Hoyer dance and was inspired by this (and other influences) to develop the Butoh . Wigman's assistant, Hanya Holm , went to America in 1931 to give her solo evenings there and to found a Wigman school. The American Martha Graham became the most important dancer, teacher and choreographer of the new art form known as Modern Dance in the USA. She also founded a school and gave modern dance a vocabulary comparable to the classical ballet code. In 1957 Martha Graham came to Germany and performed at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (West) as part of the Berliner Festwochen . (There is a picture in which Mary Wigman and Dore Hoyer stand on stage with Martha Graham after their performance: The three most important dancers in modern dance .)

Other pioneers of expressive dance in Hamburg were Gertrud and Ursula Falke , the worker dancer Jean Weidt , the mask dancers Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt. Birgit Cullberg , who is known worldwide as the founder of the ballet ensemble of the same name , and Birgit Åkesson worked in Sweden .

Kurt Jooss , who combined ballet and expressive dance, and Mary Wigman choreographed groundbreaking dance theater, e.g. B. Jooss 1932 The green table , a kind of dance of death ; Wigman 1930 her anti-war tableau memorial .

The Falke Sisters also worked with groups, and their choreographies for Laban's movement choirs were particularly impressive. His pupil Lola Rogge continued this work, took over the Labanschule in Hamburg in 1934 , which existed there under her name until the 21st century.

National Socialism

As in many other arts, the period of National Socialism interrupted the lively development of expressive dance in Germany. Many stopped dancing, took their own lives or left Germany. Some came to terms with the regime in different ways. As a "beauty dance " , nude dance and eroticism were offered in wide circles until the war years. Mary Wigman was allowed to keep her school and opened the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936 with a choreography .

post war period

After the Second World War, the heyday of pure expressive dance in Germany was over, among other things because of its involvement in National Socialism. There was still the Wigman School. She no longer danced herself, but choreographed, for example, Le sacre du printemps (The Spring Sacrifice) by Stravinsky in 1957 . Dore Hoyer gave her impressive solo evenings until her death in 1967. Beside her and influenced by her, Manja Chmièl impressed with an abstract body language. She was a student and assistant to Mary Wigman in Berlin. Jean Weidt returned from exile in France and created a new form of expressive dance in the early years of the GDR, which, however, was not widely recognized due to its obvious closeness to the state. Jean Weidt was appointed to the Komische Oper Berlin by the opera director Walter Felsenstein and from 1966 he helped set up Europe's most modern and successful dance theater under the direction of Tom Schilling .

The influence of modern dance was so strong, however, that many choreographers now combined elements of expressive dance and ballet to form dance drama, a form of theater dance that contains both. The end of the antagonism between modern dance and classical ballet was the premiere in the USA of the Episodes (1959), choreographed jointly by Balanchine and Martha Graham . Former Graham students, especially Merce Cunningham , gave ballet new impetus. They developed experimental ballet styles that incorporate the experience of two world wars and increasing human environmental degradation.

today

At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century there are all sorts of dance groups whose choreographies were influenced by expressive dance. Almost every dance education now also includes the subject of modern dance . Young dancers are taking up the art of solo expressive dance again. For example, they worked on Dore Hoyer's dances of human passions ( Afectos humanos ). Many solo dancers today are also choreographers (for example Susanne Linke , Reinhild Hoffmann , Ismael Ivo and Arila Siegert ).

Well-known choreographers working in Germany include William Forsythe , Sergej Gleithmann , Daniela Kurz , Raimund Hoghe , Constanza Macras , Felix Ruckert , Arila Siegert and Sasha Waltz .

literature

Dance history (selection)

- Hermann and Marianne Aubel: The Artistic Dance of Our Time. The blue books. KR Langewiesche, Leipzig 1928, 1935; Reprint of the first edition together with materials on the history of the edition. Introductory essay by Frank-Manuel Peter . Edited by the Albertina Vienna. Langewiesche, Königstein i. Ts. 2002. ISBN 3-7845-3450-3 .

- Walter Sorell: Knaur's book about dance. The dance through the centuries . Droemer Knaur, Zurich 1969.

- Rudolf Maack: Dance in Hamburg. From Mary Wigman to John Neumeier . Christians, Hamburg 1975. ISBN 3-7672-0356-1 .

- Hedwig Müller : The foundation of expressive dance by Mary Wigman. Cologne, Phil. Diss. 1986.

- Nils Jockel, Patricia Stöckemann: " Flying power in golden distance ...", stage dance in Hamburg since 1900 . Museum of Arts and Crafts, Hamburg 1989.

- Gunhild Oberzaucher-Schüller , Alfred Oberzaucher , Thomas Steiert: Expressive dance: a Central European movement of the first half of the 20th century . Florian Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1992.

- Silke Garms: dance women in the avant-garde. Life politics and choreographic development in eight portraits. Rosenholz, Kiel / Berlin 1998. ISBN 3-931665-11-9 / ISBN 978-3-931665-11-1 .

- Claudia Fleischle-Braun: The modern dance. History and communication concepts . Afra, Butzbach-Griedel 2000, 2001. ISBN 3-932079-31-0 .

- Frank-Manuel Peter : What is expressive dance? , in: Ders .: Between expressive dance and postmodern dance. Dore Hoyer's contribution to the advancement of modern dance in the 1930s. Dissertation. Free University of Berlin 2004, pp. 35–62.

- Amelie Soyka (Ed.): Dancing and dancing and nothing but dancing. Modern dancers from Josephine Baker to Mary Wigman . Aviva, Berlin 2004. ISBN 3-932338-22-7 .

- Rosita Boisseau: Panoram de la Danse Contemporaine. 90 Chorégraphes. Les Édition Textuel, Paris 2006. ISBN 2-84597-188-5 .

- Alexandra Kolb: Performing Femininity. Dance and Literature in German Modernism. Oxford: Peter Lang 2009. ISBN 978-3-03911-351-4 .

- Simon Baur: expressive dance in Switzerland . Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 2010. ISBN 3-7959-0922-8 .

- Hubertus Adam, Sally Schöne (Ed.): Expressive dance and Bauhaus stage . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-7319-0852-4 .

pedagogy

- Rudolf von Laban: The modern expressive dance in education. An introduction to creative dance movement as a means of developing one's personality. With the collaboration of Lisa Ullmann. Translated from English by Karin Vial. Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1981, ISBN 3-7959-0320-3 .

- Silke Garms: TanzBalance. Expressive dance for women. Rosenholz, Kiel / Berlin 1999. ISBN 978-3-931665-01-2 .

Literature on the individual dancers is listed in their entries (linked here).

Movie

In the documentary Tanz mit der Zeit (2007), Trevor Peters shows how the choreographer Heike Hennig brings modern dance history to life in the contemporary dance pieces Zeit - Tanz since 1927 and Zeitsprung at the Leipzig Opera, by Ursula Cain (Wigman student and member of Group from Dore Hoyer) to the Palucca student Siegfried Prölß .

For the layman, Karoline Herfurth offers an instructive insight into today's expressive dance in the final scenes of the film Im Winter ein Jahr (2008).

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Frank-Manuel Peter: What is meant by "expressive dance"? In: Ders .: Between expressive dance and postmodern dance. Dore Hoyer's contribution to the advancement of modern dance in the 1930s. Dissertation. Freie Universität Berlin 2004, pp. 35–62, here pp. 35ff .; Horst Koegler and Helmut Günther: Reclams Ballettlexikon . Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1984, p. 27.

- ↑ 27 forms of culture included in the German directory of intangible cultural heritage

- ^ Modern dance , Georg Müller, Munich, 3rd edition 1921, p. 4

- ↑ Meyers Lexikon , 7th ed., 11th volume, Leipzig 1929, keyword dance , esp. Sp. 1294f.

- ↑ Order No. 48 of the President of the Reich Theater Chamber regarding examination regulations for dancers and teachers of artistic dance , in: Singchor und Tanz , H. 7/8 1935, Amtl. Garnish; also in: Der Tanz , September 1935, p. 8f.

- ↑ Hedwig Müller: The foundation of expressive dance by Mary Wigman. Phil.-Diss., Cologne 1986, p. 6.

- ↑ Hedwig Müller, Frank-Manuel Peter, Garnet Schuldt: Dore Hoyer. Dancer. Hentrich, Berlin 1992. ISBN 3-89468-012-1 , p. 59.

- ↑ Winter 42/43 ( memento of January 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), documentary, broadcast by ARD on January 7, 2013, 41st minute, accessed on January 8, 2013