Canine anaplasmosis

The Canine anaplasmosis is a by tick borne infectious disease of the dog by, bacteria of the genus Anaplasma is caused. It is one of the vector-based dog diseases . The disease caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum was formerly known as "granulocytic Ehrlichiosis". A. phagocytophilum also affects other mammals and humans (→ human granulocytic anaplasmosis ), so the disease is a zoonosis . However, the (rare) human infections caused by this pathogen only come about through infection via ticks, transmission from dog to human is unlikely, but theoretically possible with direct blood contact.

In most cases, the infection is silent in the dog , so there are no symptoms of the disease. Strongly disease-causing strains of the pathogen can also cause severe forms. Typical symptoms are fever, punctiform bleeding and nosebleeds. Treatment is usually done with doxycycline .

Pathogen and occurrence

Anaplasmas are Gram- negative proteobacteria from the order of the Rickettsiales . The causative agent of canine anaplasmosis is Anaplasma phagocytophilum . It is an exclusively intracellular (obligate intracellular) bacterium that attacks a subgroup of white blood cells called granulocytes . Since the pathogen was previously included in the Ehrlichia genus , the disease is referred to in the older literature as " Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis ".

In addition to dogs, A. phagocytophilum is also disease-causing in other mammals, including humans. The common wood tick ( Ixodes ricinus ), a common type of tick in Europe , acts as a vector . In Northern Europe the taiga tick ( Ixodes persulcatus ) also plays a role, in North America the pathogen is spread by the deer tick ( Ixodes scapularis ). The infection with A. phagocytophilum occurs all over Northern and Central Europe and is also common in Germany , in contrast to canine Ehrlichiosis, which only occurs in the Mediterranean area . The pathogen is transmitted during the suction act after 24 to 48 hours.

In the past, the disease was mainly observed in Switzerland ("Swiss Ehrlichiosis"). More recent studies have also shown a relatively frequent occurrence in Germany. The seroprevalence in dogs in Germany fluctuated between 19 and 50% in current studies and, like in Switzerland, around one percent of the wood tucks are carriers of the pathogen. According to the current state of knowledge, the pathogen is not eliminated after the disease has been overcome or the treatment has been successful, i.e. once infected animals remain carriers of the pathogen for life.

A second type of Anaplasma that causes disease in dogs is Anaplasma platys . It actually comes from America , but now there are natural herds in the extreme south of Europe. A. platys is transmitted by the brown dog tick and causes canine cyclic thrombocytopenia .

Symptoms

The incubation period is 2 to 20 days. The consequences of an infection vary widely, but the majority of dogs show no symptoms. However, depending on the disease-causing potency of the pathogen strain and the immune system of the animal, serious clinical pictures can also occur.

A clinically manifest disease caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum usually results in fatigue, fever and unwillingness to eat. Typical is a decrease in blood platelets ( thrombocytopenia ) with a tendency to bleeding, which occurs in 80% of cases. Nosebleeds, punctiform bleeding of the mucous membranes and organ bleeding are therefore observed very frequently . The inflammatory reactions triggered by the organ bleeding can, depending on the organ system affected, lead to coughing, increased drinking, gastrointestinal symptoms and neurological disorders such as seizures, ataxia and proprioceptive deficits.

In addition, muscle hardening, polyarthritis with joint pain, joint swelling and lameness, and weight loss can occur. In the case of a simultaneous infection with Borrelia (→ Borreliosis ), which are also transmitted by the Holzbock, the symptoms are usually more pronounced.

In addition to thrombocytopenia, the blood count often shows a decrease in the lymphocytes, which are also part of the white blood cells ( lymphopenia ), anemia without sufficient blood regeneration but with normal blood pigment content (non-regenerative normochromic anemia ), a deficiency in blood protein albumin ( hypoalbuminemia ), and an increase in Detect defensive proteins in the blood ( hyperglobulinemia ) as well as an increase in alkaline phosphatase and C-reactive protein .

Diagnosis

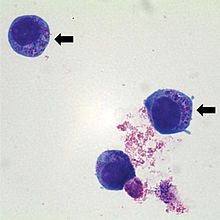

The detection of 2–5 µm large, mulberry-like inclusions ("morulae") within the neutrophil granulocytes in the colored blood smear is a simple method for the detection of pathogens. These "morulae" arise from the multiplication of bacteria within vacuoles of the cytoplasm , which creates so-called elementary bodies which aggregate to form inclusion bodies . However, only positive evidence is conclusive, as some diseases proceed without the formation of morula. There is also a rapid test for the detection of a surface protein (p44 / MSP2), with which the C6 peptide of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and thus a co-infection with Borrelia can also be detected.

About 10 to 14 days after infection or two to five days after the appearance of morulae, antibodies against A. phagocytophilum can be detected by means of an indirect immunofluorescence test (IFAT). The titers increase in the first two to three weeks and can fall below the detection limit again after seven months. The problem is that about 40% of the dogs are still seronegative at the time of the disease and due to the long persistence of the antibodies, an acute case of the disease does not have to be related to the A. phagocytophilum infection. Antibody detection is therefore not suitable for diagnosing acute anaplasmosis.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enables direct detection of the pathogen's DNA and differentiation between A. phagocytophilum and A. platys , between which there is cross-reactivity in the serological tests . PCR detection is possible about a week before the morulae appear. PCR detection in the blood is possible from the second day after infection up to a period of three to six weeks. Despite the suspected persistence of the pathogen, this evidence is therefore suitable for the detection of an acute infection. Since many dogs go through a silent infection, a positive PCR is no proof that the disease is actually anaplasmosis.

Since none of the procedures allows a reliable diagnosis, three main criteria must be met for a definitive diagnosis:

- positive direct pathogen detection (PCR or morulae)

- Thrombocytopenia

- Platelet count increase within a few days of treatment with doxycycline

Treatment and prevention

Therapy takes place with antibiotics such as doxycycline , tetracycline and oxytetracycline for two to four weeks. Treatment should only be carried out when clinical symptoms are present, i.e. not when the infection is silent. The platelet count should be monitored to control therapy. There is no preventive vaccination. However , an infection can be prevented by regular monitoring and immediate removal of ticks or by using active ingredients that repel ticks (e.g. permethrin or deltamethrin ).

literature

- Peter F. Suter: Ehrlichiosis, anaplasmoses, neorickettsioses (Rickettsiales infections, dog rickettsiosis, canine rickettsiosis) . In: Peter F. Suter and Barbara Kohn (eds.): Internship at the dog clinic . 10th edition. Paul Parey, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-8304-4141-0 , pp. 299-302 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Michèle Bergmann and Katrin Hartmann: Anaplasmosis in dogs - infection common, disease rare . In: small animal specifically . tape 18 , no. 5 , 2015, p. 3-7 , doi : 10.1055 / s-0035-1558509 .

- ↑ Rolf Bauerfeind: Zoonoses: infectious diseases that can be transmitted from animal to human . Deutscher Ärzteverlag, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-7691-1293-1 , p. 213 .

- ↑ a b c Barbara Kohn: Anaplasma phagozytophilum: New studies on prevalence, clinical features and prophylaxis . In: Small Animal Medicine . No. 3/4 , 2010, p. 98-106 .

- ↑ Stefan Pachnicke: Vector prophylaxis : Indirect reduction of the risk of transmission for CVBD pathogens. In: The practical veterinarian . tape 97 , no. 5 , 2016, p. 468-469 .

- ↑ D. Schaarschmidt-Kiener and W. Müller: Laboratory Diagnostic and Clinical Aspects of Canine Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis . In: Tierärtl. Practice . tape 35 , 2007, p. 129-136 .

- ↑ a b c d e Nikola Panchev: Canine granulocytic anaplasmosis in dogs - Part 2: Diagnostics, therapy and prophylaxis . In: Tierärztl. Journal . tape 2 , 2010, p. 132-133 .

- ↑ Rolf Bauerfeind: Zoonoses: infectious diseases that can be transmitted from animal to human . Deutscher Ärzteverlag, Cologne 2013, ISBN 978-3-7691-1293-1 , p. 211 .