Chapey dang veng

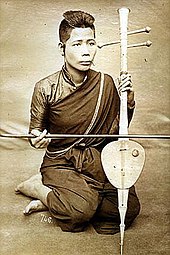

Chapey dang veng , also chapay dang veng, chapei dong veng ( Khmer ចាប៉ី ដង វែង ), chapei veng , chapey ( ចាប៉ី ) for short , is a long-necked lute with two or four strings and a large rounded body that is played in Cambodian traditional music in Thailand corresponds to krajappi ( Thai กระจับปี่ ), which became rare around the middle of the 20th century . The chapey dang veng is used for song accompaniment ( chrieng chapey ), in wedding music ensembles ( phleng kar ) and in rural areas in ceremonial ensembles ( phleng arak ) that perform in necromancy rituals . The instrument name chapey comes from India and goes back to Sanskrit kacchapi ("turtle"), the shape is related to the "moon sounds" occurring in East Asia and Vietnam , which are so called because of their circular, flat body. In 2016 that was Chapey dang veng by the UNESCO in the list of urgent conservation need of the Intangible Cultural Heritage added.

Origin and Distribution

From the middle of the 1st millennium, the area of today's Cambodia, which at that time belonged to the Chenla State Union and from the beginning of the 9th century to the Khmer Empire , was under the influence of Indian culture. The Hindu and Buddhist temples, especially in the medieval capital Angkor, bear witness to Indian culture . On some temple reliefs there are depictions of Indian bow harps ( vina ), which were in use in India up to the 7th century, and staff zither of a simple type that has practically disappeared in India and is now only in a retreat in East India with the name tuila , in Cambodia as kse diev and in Thailand as phin nam tao . A relief on the bayon shows a vertical lute with a small round body, which however has nothing to do with the shape of the chapey . In written sources of the high culture of the Khmer some names for stringed instruments are handed down, but they can hardly be assigned to one type of instrument. Long-necked lutes with a slender, pear-shaped body and three to five strings, as found on reliefs on the Indian stupas of Amaravati (2nd century AD) and Nagarjunakonda (around 4th century AD), are for medieval Cambodia not established. Likewise , no corresponding long-necked sounds are known in Indonesia , which was visited by Indian traders and missionaries from the first centuries AD. Of the long-necked boat sounds of the sape type that are common on some Southeast Asian islands , some in the Philippines have names derived from the Sanskrit word kacchapi for an ancient Indian long-necked sound (such as kutiyapi ), but this type of instrument is unknown in India.

Overall, the influence of Indian music on Southeast Asia was rather small and is not recognizable even with the chapey , after all, like krajappi in Thai, her name goes back to Sanskrit kacchapi . It is not uncommon for an instrument name to disappear in one region and reappear elsewhere for another type of instrument. The two-stringed Indonesian spiked fiddle , rebab , for example, shares its name from the Arabic root r – b – b (often vocalized as rabāb ) with various oriental string and plucked instruments and after sitar for an Indian long-necked lute, a variant of the box zither celempung is named in West Java with siter . The term kacchapi for a stringed instrument is first mentioned in Bharata Muni's work on the performing arts Natyashastra at the turn of the times, when the Gandhara Empire in northwest India was under Greek influence . Curt Sachs (1923) reflects the assumption that the word kacchapi , which means "turtle" in Sanskrit and Pali , could be analogous to the Greek word cheloni for a plucked instrument with a turtle shell as a resonator, which is derived from chelys ("turtle"), have been transferred to an Indian string instrument. This transfer of meaning would have to have taken place regardless of the shape, for stringed instruments with turtle shells never appeared in India, unless an illustration of Gandhara art with a simple, early type of a three-stringed short-necked lute is considered to be a turtle shape. A practical derivation of the name takes into account that kacchapi can also refer to the tree Cedrela tuna (family of the mahogany plants ), the wood of which is still used today for the construction of the sitar .

Language related in Indonesia are kacapi for a board zither in West Java and hasapi for a narrow two-string plucked lute on the island of Sumatra , the sape in Borneo also belongs to this much larger word context, which, according to Walter Kaudern (1927), predates the Hindu period which spread Islamization in the Malay Archipelago in the 13th century in North Sumatra and in the early 15th century on Java . Kaudern sees the geographical distribution of the word kacchapi as being linked to the maximum extent of the last Hindu empire Majapahit . The size and outline of the chapey body can be related to a turtle, but the association with the other string instruments mentioned in Southeast Asia does not fit.

The collapse of the Khmer Empire in Cambodia was followed by Siamese coming to power in the 15th century , which now culturally influenced an area in which music was practically only practiced on a village level until the 19th century. Most Cambodian musical instruments therefore have Thai equivalents, which at best differ from one another in terms of shape and playing style. The Thai counterpart to the chapey dang veng and the link to its further origin and distribution is the three-stringed long-necked lute krajappi , which was played in the classical Thai music genre mahori - corresponding to the Cambodian mohori - and in the khrung sai ensemble until the 19th century . The latter is today, as the name suggests, a "string instrument ensemble". Other stringed instruments in mahori are the three-stringed tubular spear violin sor sam sai (in Cambodia tro khmer ) and the two-stringed sor u (in Cambodia tro ou ). In addition, in a complete younger mahori ensemble, there are two xylophones that are close to the Cambodian roneat , ranat ek and ranat thom (high and low tuned), the two hump gong circles khong wong lek and khong wong yai (high and low tuned), the hand cymbals ching as well as the drum pair thon and rammana.

The only Thai wall painting on which such an ensemble with string instruments, xylophones and drums can be seen is on the outer wall of the gallery in Wat Phra Keo (Bangkok, School of Rattanakosin , second quarter of the 19th century, restored several times from 1880). All the musicians are asleep on the floor. A smaller, making music mahori ensemble with a sitting in the middle krajappi -Spielerin is Wat Suwandararam in Ayutthaya from the time of Rama I see (reg. 1782 to 1809) and in the Buddhaisawan Chapel, the National Museum Bangkok belongs . The oldest wall paintings in the state capital can be found in the chapel, which was built in 1795. This music scene represents an older form of a mahori ensemble only occupied by women with sor sam sai, krajappi , bamboo flute khlui , beaker drum thon and occasionally the flat drum rammana, rattle krap phuang and ching . Another scene in the Buddhaisawan Chapel shows the god Indra and his companion Pancasikha, which only occurs in the Buddhist tradition, as both descend from heaven in flight. Pancasikha belongs to the heavenly musicians ( Gandharvas ) and is usually depicted with an arch harp, but here with a krajappi . He holds the krajappi , on which three strings and five pegs can be recognized, in the usual lute position with two hands at an angle in front of the upper body and shakes small hourglass drums ( damaru ) with two other hands at head height . The krajappi has largely disappeared since the middle of the 20th century and is only occasionally played as a soloist.

The plucked long-necked lute was the rarest of the three Thai stringed instrument types. The best-known type is the three-string zither chakhe , which corresponds to the Cambodian krapeu and the Burmese mí-gyaùng and, because of their shape, is counted among the “crocodile zithers ”. It probably comes from India, where a number of zoomorphic zithers are known, such as the peacock-shaped mayuri vina . The oldest of the stringed sounds in Thailand under the collective name sor come from China. Since the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) they have had the name huquin (about "fiddle of the foreigners in the north"), which refers to the origin of the spiked fiddle among the steppe nomads in Mongolia . Such a distant origin of krajappi and chapey dang veng cannot be identified.

One of the earliest mentions of the krajappi in European literature is a report by the English ethnologist and orientalist John Crawfurt, who describes the krajappi as a "guitar with four strings" and is one of the ten instruments that, in addition to two gong circles ( khong wong yai ) , a three-string fiddle, a four-string boat-shaped instrument ( takhe , crocodile zither) and a flute ( khlui ) made up a Siamese orchestra. In the description of the Siamese musical instruments by the English traveler Frederick Arthur Neale (1852), the krajappi is a banjo that consists entirely of a "long-necked pumpkin" covered with parchment and is strung with four to six strings. Other descriptions from the second half of the 19th century confirm the krajappi sound box made from a calabash . In the last known historical mention of the krajappi , a travel report by Maxwell Sommerville from 1897, an astonishingly large orchestra is presented - if the information is correct - with ten krajappi , trough xylophones ( ranat ), humpback gong circles ( khong wong ), crocodile zithers ( takhe ) and single-headed drums ( rammana ).

The geographically closest long-necked lute are the somewhat smaller, two- to four-string phin in northeastern Thailand ( Isan ) and Laos, and the four-string sueng in northern Thailand . More closely related are the East Asian and Vietnamese "lunar lutes", whose name refers to their circular, large and flat body. These include the four-string Chinese yueqin with a short neck (in Japan, gekkin ) and the Chinese ruan , which is said to be very old. The chapey dang veng connects the shape of the body with the lunar sounds , while the neck was probably elongated under the influence of the regional spiked fiddle .

The Chinese three-stringed sanxian , whose name was already known in the Tang dynasty (618–907) and is depicted on Chinese rock paintings of the 12th century, has a smaller body, but a very long, thin neck corresponding to the Cambodian lute . In Japan it is called shamisen . The rare Vietnamese nichtàn đáy , which is a combination of the two-string Vietnamese lunar lute đàn nguyệt and the long three-string skewer lute đàn tam with a rounded small one, has a not round, but trapezoid-edged, flat body with an equally slender neck Represents corpus. The đàn nguyệt with two strings made of silk or nylon, described by the Belgian musicologist and composer Gaston Knosp (1907) as a “four-string guitar with a circular sound box” because it was apparently equipped with double strings made of silk around 1900, has a longer neck than other lunar lutes , a size ratio between body and neck that is more similar to the chapey dang veng .

Design

Chapey dang veng means "lute with a round fingerboard"; an old name is chapey thom ("big lute"). The thick-walled body ( snauk ), carved from a piece of wood, is as big as the lunar lute, approximately round or square with strongly rounded corners. At the base of the neck, a solid wood protruding about ten centimeters into the interior of the body remains, to which the long, slim neck ( dang ) is glued. The glued, flat, thin wooden ceiling ( santeah ) has no sound hole or a small circular hole ( run santeah ) in the middle. The strings run from a tailpiece attached to the edge of the body over a bridge ( kingkuok ) located in the lower third of the top to long lateral vertebrae, above which the neck ends in an elegant curve to the rear. The lute is covered with two single strings or two double strings made of twisted silk or, with today's instruments, made of nylon. The strings are tuned to quarters apart and are usually plucked with an animal horn plectrum. They lead over 12 or 13 high on the neck, glued with black wax frets made of hardwood or bone. The position of the frets can be changed with the removable wax. The melody is played almost exclusively on the high string ( khse aek ), while the low string ( khse ko ) serves as a drone .

The types of wood used for the individual components must be carefully selected because the sound should not only be pleasing to the audience in the ritual music but also to the spirits. That is why different woods are used for the body, neck, top and bridge. Jaques Brunet (1979) gives a total length of 130 to 170 centimeters, depending on the design of the neck end. A measured specimen has a total length of 140 centimeters, a neck length of 105 centimeters, a body measuring 30 × 34 centimeters, the height of which is 6 centimeters and a freely vibrating string length of 85 centimeters.

With the same range of variation in forms, Cambodian sounds can hardly be distinguished from the Thai models. A typical krajappi is up to 180 centimeters long and has a 138 centimeter long neck, its body measures 44 centimeters in length, 40 centimeters in width and 7 centimeters in depth. At first the krajappi was covered with gut strings, later with strings made of silk or nylon. The strings are adjusted to the accompanying instruments on g – d (for the interplay with the sor duang ) or on the fifth c 1 –g 1 (for the sor u , corresponding to the Khmer fiddle tro ou ).

The chapey tauch ( chapey toch, "higher", "smaller" chapey ) with a short neck like Chinese moon sounds has disappeared. Around 1900 this smaller lute seems to have been played by women of the royal palace, apparently it was given up because of the low tone and the poor sound quality.

Style of play

The Thai krajappi was used until the end of the 19th century in the old mahori ensemble ( mahori boran ), which consisted of at least four instruments: krajappi , three-stringed fiddle sor sam sai , beaker drum thon and the krap phuang (one of six to ten existing wooden slats between two more rigid wooden rods Klapper ).

In addition to the originally courtly Khmer orchestra pin peat (in Thailand pi phat ), which is dominated by xylophones and gong circles and which today accompanies courtly dance styles, some forms of theater, the shadow play sbek thom and monastic ceremonies, there are a number of other ensembles that are specifically at occur on certain occasions. The mohori has no ceremonial function, it is used for general entertainment and to accompany folk dances. By 1900 it was Mohori according Gaston Knosp against the pi phat male musicians "more tender woman orchestra" with some of the pin peat acquired percussion instruments as well as the spike fiddle tro ou (he with " ravanastron translated") and the "big" ( Chapey thom , meant chapey dang veng ) and the "small" long-necked lute ( chapey toch ).

Chrieng chapey

Folk music includes the narrative style of singing chrieng chapey, which is often performed at village weddings accompanied by chapey dang veng . In chrieng chapey , a mostly male singer plays the lute himself ( chrieng , "to sing", so "to sing the lute"). Street singers delivered part of the Cambodian folk tales by going from village to village and performing in the evenings in front of a crowd that had gathered in front of the Buddhist monastery. The performances could last half a night or all night. In the meantime it was important to keep the audience happy with exciting or funny stories, including improvised stories about current events. Before the start of the reign of terror by the Khmer Rouge in 1975, the focus was on fantastic-mythical folk tales such as Preah Chinavung, Hang Yunn and Preah Chan Korup , which are popular alongside the Reamker , the Cambodian adaptation of the Indian epic Ramayana . Since the complete social and cultural new beginning in 1979, the old legends have been supplemented by descriptions of the reign of terror and current topics. With chrieng names used in the Thai region of Isan from the mouth organ is khaen accompanied vocal style chariang .

Phleng kar

The vung phleng kar , traditional wedding music, is the most popular folk music ensemble among Cambodians. The old “original” wedding music ensemble , which is one of the oldest Khmer music genres and existed until the middle of the 20th century, is the phleng kar boran . Another name is krom phleng Khmer . Its instrumentation consists of the cylindrical double reed instrument pey prabauh with an approximately 30 centimeter long playing tube made of wood or bamboo (related to the Korean piri , the Chinese guan and the Japanese hichiriki ), according to whose pitch the stringed instruments are tuned, the single-stringed zither kse diev ( also khse Muoy ), the three-stringed sting violin tro khmer (also tro KSAE in similar to the Javanese Rebab ), the Chapey dang veng , two beaten with hands cup drums skor arak , hand cymbals ching from brass, consisting of a folded sheet free Mirliton slekk and a singing voice neak chrieng.

Today's wedding music ensemble, called phleng kar kondal ("semi-traditional wedding music"), is composed, according to Kathey M. McKinley (1999), in addition to a singer and a female singer of four instrumentalists who play a two-stringed spiked violin with a cylindrical resonator tro sao ( in Thailand sor u ), a crocodile zither takhe , a trapezoidal dulcimer khim (m) with 14 three-horned strings ( derived from the Chinese yangqin ) and the beaker drum skor arak . This ensemble can be expanded to include another beaker drum, a two-string fiddle and cymbals played by one of the singers.

Gisa Jähnichen (2012) describes a phleng kar ensemble that, including the singing voice, should consist of at least seven musicians. The instruments include the two spiked fiddles tro so tauch (in Thailand sor duang ) and tro ou , the chapey dang veng , the crocodile zither takhe , the dulcimer khim , the bamboo long flute khloy (in Thailand khlui ), the hand cymbals ching , the single-headed flat one Drum skor rumanea (in Thailand rammanea ) and the tumbler drum skor arak .

The singing voice has phonetic improvisation possibilities within a melody framework that is fixed for each piece and makes use of recurring universal phrases. The musical instruments are divided into four groups according to their musical task. The quill fiddles (and the flute) of the first group play the melody line, while the chapei dang veng and the dulcimer khim fill the melody with intermediate notes . The third group consists of the drums used for the rhythmic structure. Finally, the cymbals determine the metric accentuation and dictate the tempo and changes in tempo. Each piece of music opens with a free rhythmic solo of one of the instruments, in which the basic melodic structures are introduced for the other members of the ensemble.

The musicians, who are usually engaged as amateurs, are involved in a detailed sequence of ceremonies during the wedding ( kar ). The main part of the celebration, which begins after breakfast, consists of at least eight activities, including: the bride and groom have their hair cut, the bride washes the groom's feet, the groom presents betel palm flowers to the parents, the bride and groom are tied a cotton thread on their wrists and various spirits and ancestral spirits are summoned. During and between the individual actions, the musicians play a total of 20 to 30 standardized pieces of music from the phleng kar repertoire and, to a small extent, from the entertainment genre mohori . The participants in the wedding do not dance to the music and do not have any influence on it. The main purpose of the music, which must always come from a live band, is to structure the overall process, which also creates a time frame for the individual activities.

Phleng arak

The ensemble phleng arak or vung phleng arakk is specially designed to worship spirits . During the necromancy ceremony ( arak , the ancestral spirits are also collectively called arak or bai sach ), a medium goes into a trance to find out the cause of an illness. The Chinese envoy Zhou Daguan , who visited Angkor from 1296–1297, reported in his travel report that there were magicians who practiced their healing arts on the Cambodians. Herbal medicine and magical practices, which are based on an animistic conception of omnipresent spirits affecting people, are among the healing methods that are in demand to this day, especially in rural areas with inadequate medical care . Disease is therefore caused by angry spirits. Therefore, a magical healer is invited to perform a ceremony called banchaul roup (“enters the body”) or banchaul arak (“the guardian spirit enters”) during his trance . First, however, the expertise of a village elder must be sought in order to find a suitable medium for the individual case. Then the relatives of the sick person engage a phleng arak ensemble and procure the necessary offerings until the ceremony with the sick person , the healer and the musicians takes place on the agreed day and place.

The phleng arak consists of a stick zither kse diev , a spiked fiddle tro khmer , a chapey dang veng , a double reed instrument pey prabauh , a beaker drum skor arak , hand cymbals ching and singers neak chrieng . Not for the music of the ensemble, but for the opening of the ceremony and the invocation of the great teacher ( krou thomm ) named Samdech Preah Krou (a guardian spirit who also participates in the courtly Khmer dance), two other musical instruments used as soloists are required: the single-reed instrument pey pork from a bamboo tube with a brass reed and the animal horn sneng . The opening is followed by the phase of trance with the questioning of the spirits, followed by a final thanksgiving. The music is essential for the success of the ceremony.

While the phleng arak ensemble is gradually disappearing, especially in the cities, as a result of improved medical facilities, the phleng kar ensemble has gone beyond its originally purely functional role in the wedding ceremony and is now also performed in concerts and broadcast on television.

literature

- Terry E. Miller: Chapay dang veng. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments . Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 505

- Sam-Ang Sam, Panya Roongruang, Phong T. Nguyễn: The Khmer People . In: Terry E. Miller, Sean Williams (Eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 4: Southeast Asia. Routledge, London 1998, pp. 151-216

Web links

- Khmer Chapei Dong Veng. Youtube video

- Chapey (song) for World Population Day, 11 July 2011 by H. Vongdara (assisted by Wathakna). Youtube video

- Ancient possession music - Phleng arak boran. Youtube video (from left to right: beaker drum skor arak , double reed instrument pey prabauh or pei ar , fiddle tro Khmer , rod zither kse diev and chapey dang veng )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Chapei Dang Veng . UNESCO, December 2016

- ^ Roger Blench: Musical instruments of South Asian origin depicted on the reliefs at Angkor, Cambodia. EURASEAA, Bougon, September 26, 2006, p. 4f

- ↑ See Saveros Pou: Music and Dance in Ancient Cambodia as Evidenced by Old Khmer Epigraphy. In: East and West , Vol. 47, No. 1/4, December 1997, pp. 229-248, here p. 236

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume II. Ancient Music. Delivery 8. Ed. Werner Bachmann. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, p. 36

- ↑ Hans Brandeis: An attempt at a typology of Philippine boat sounds. In: Eszter Fontana , Andreas Michel, Erich Stockmann (eds.): Studia instrumentorum musicae popularis, Volume 12. Janos Stekovics, Halle 2004, pp. 75–108, here p. 104

- ^ Artur Simon : The Terminology of Batak Instrumental Music in Northern Sumatra. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music, Vol. 17, 1985, pp. 113-145, here p. 115

- ^ Curt Sachs : The musical instruments of India and Indonesia . 2nd edition (1923). Reprint Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1983, p. 125

- ↑ Emmie te Nijenhuis: Dattilam. A Compendium of Ancient Indian Music. Ed .: K. Sambasiva Sastri, Trivandrum Sanskrit Series no.102 , Trivandrum 1930, p. 83

- ^ Walter Kaudern: Ethnographical studies in Celebes: Results of the author's expedition to Celebes 1917–1920. III. Musical Instruments in Celebes. Elanders Boktryckeri Aktiebolag, Göteborg 1927. p. 192

- ^ David Morton: The Traditional Music of Thailand. University of California Press, Berkeley 1976, p. 92

- ↑ Terry E. Miller, Sam-ang Sam: The Classical Musics of Cambodia and Thailand: A Study of Distinctions. In: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 39, No. 2, Spring – Summer 1995, pp. 229–243, here pp. 230, 233

- ↑ Terry E. Miller: The Uncertain Musical Evidence in Thailand's Temple Murals . In: Music in Art , Vol. 32, No. 1/2 ( Music in Art: Iconography as a Source for Music History, Vol. 3) Spring – Autumn 2007, pp. 5–32, here p. 10f, illustrations p 19f

- ↑ Monika Zin : Devotional and ornamental paintings . Volume 1. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 155

- ^ Jean Boisselier : Painting in Thailand . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1976, p. 95

- ↑ Krajappi . In: Grove Music Online, February 11, 2013

- ↑ John Crawfurt: Journal of an embassy from the governor-general of India to the courts of Siam and Cochin China; exhibiting a view of the actual state of those kingdoms. Volume 2, 2nd edition, Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, London 1828, p. 37

- ↑ Frederick Arthur Neale: Narrative of a residence at the capital of the Kingdom of Siam, with a description of the manners, customs, and laws of the modern Siamese. Office of the National Illustrated Library, London 1852, pp. 236f

- ↑ Terry E. Miller, Jarernchai Chonpairot: A History of Siamese Music Reconstructed from Western Documents, 1505-1932 . In: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1994, pp. 1–192, here p. 78

- ↑ Curt Sachs, (1923) 1983, p. 133

- ^ Alan R. Trasher: Sanxian . In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ^ Gisa Jähnichen: Uniqueness Re-examined: The Vietnamese Lute Đàn đáy. In: Yearbook for Traditional Music , No. 43, 2011, pp. 26-48

- ↑ Trân Quang Hai: Đàn đáy. In: Grove Music Online, September 22, 2015

- ↑ Gaston Knosp: About Annamite Music . In: Anthologies of the International Music Society, Volume 8, Volume 2., 1907, pp. 137–166, here p. 140

- ↑ Alessandro Marazzi Sassoon: My Phnom Penh: Keat Sokim Musician. The Pnom Penh Post, Dec 9, 2016 (Photo of a chapey workshop)

- ↑ Terry E. Miller, 2014, p. 505

- ^ The Music of Cambodia. Volume 3. Solo Instrumental Music Recorded in Phnom Penh. CD produced by David Parsons. Celestial Harmonies, 1994, title 3, 8, 13, text supplement: John Schaefer

- ^ Jacques Brunet: L'Orchestre de Mariage Cambodgien et ses Instruments. In: Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, Vol. 66, 1979, pp. 203-254, here pp. 219-221

- ^ Europeana Collections. (Photo of a krajappi before 1913) - Museum of Fine Arts Boston. (Photo of a krajappi before 1993)

- ↑ Krajappi . In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Vol. 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 213

- ↑ Terry E. Miller: Thailand. In: Terry E. Miller, Sean Williams (Eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music . Volume 4: Southeast Asia . Routledge, London 1998, pp. 237f

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : Musical Instruments: A Comprehensive Dictionary. A complete, authoritative encyclopedia of instruments throughout the world. Country Life Limited, London 1966, p. 89, sv Cha pei toch

- ^ Jacques Brunet, 1979, p. 219

- ^ David Morton: The Traditional Music of Thailand . University of California Press, Berkeley 1976, illustration p. 102

- ↑ Gaston Knosp, 1907, p. 155

- ↑ Man Yahya: Preah Chan Korup . khmerlegends.blogspot.com, April 24, 2014

- ↑ Sam-Ang Sam, Panya Roongruang, Phong T. Nguyễn, 1998, p. 202

- ↑ Sang-Am Sam, Patricia Shehan Campbell: Silent Temples, Songful Hearts: Traditional Music of Cambodia . World Music Press, Danbury 1991, illustration p. 44

- ↑ Sam-Ang Sam, Panya Roongruang, Phong T. Nguyễn, 1998, p. 196

- ↑ Kathey M. McKinley: Tros, Tevodas, and haircuts: Ritual, Music, and Performance in Khmer Wedding Ceremonies. In: Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1999, pp. 47–60, here p. 53

- ^ Gisa Jähnichen: The Spirit's Entrance: Free Metric Solo Introductions as a Complex Memory Tool in Traditional Khmer Wedding Music. In: Gisa Jähnichen, Julia Chieng (Ed.) Music & Memory. ( UPM Book Series for Music Research IV ) UPM Press, Serdang 2012, pp. 51-70, here pp. 53f

- ↑ See Cambodia: Traditional Music, Vol. 1: Instrumental and Vocal Pieces. LP by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings (FW04081), 1975, page 1, track 3: Krom Phleng Khmer ( booklet )

- ↑ Gisa Jähnichen, 2012, pp. 51, 54

- ↑ Kathey M. McKinley, 1999, pp. 54f

- ↑ Eve Monique Zucker: Transcending Time and Terror: The Re-Emergence of “Bon Dalien” after Pol Pot and Thirty Years of Civil War . In: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 37, No. 3, October 2006, pp. 527-546, here p. 540

- ↑ Sam-Ang Sam, Panya Roongruang, Phong T. Nguyễn, 1998, p. 194

- ↑ Francesca Billeri: The Process of Re-Construction and Revival of Musical Heritage in Contemporary Cambodia. In: Moussons - Recherche en sciences humaines sur l'Asie du Sud-Est, No. 30, 2017