Commentariolus

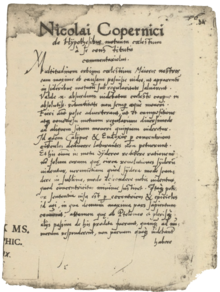

Commentariolus ( Latin for small comment ) is the short name of a manuscript that was only found again in 1877 , the text of which is attributed to Nicolaus Copernicus . It bears the full title Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus (for example: Nikolaus Copernicus' little commentary on the hypotheses of the movements of the heavenly bodies, which were put forward by himself ). The existence of the Commentariolus was previously only known through a brief remark by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in one of his works. It was written well before the publication of Copernicus' main work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium . In it, Copernicus already designed his heliocentric view of the world , in which all planets, including the earth, move around the sun without, however, substantiating it mathematically.

At present, three copies of the Commentariolus are known, which differ from each other in the way they were copied , and which were found in libraries in Vienna , Stockholm and Aberdeen . An autograph that goes back to Copernicus has not yet been discovered. The exact time when Copernicus wrote the Commentariolus is not known. It was probably written before May 1514. It is usually assumed that the Commentariolus was written around 1509, i.e. towards the end of Copernicus' stay in Heilsberg . Nothing certain is known about the contemporary distribution and reception of the Commentariolus .

Find history

The first copy of the Commentariolus was discovered in 1877 by Maximilian Curtze in the Vienna Court Library . He found it in a under the order number 10530 registered quarto , which consisted of 45 pages. This copy was bound in a cardboard volume with a parchment spine and a green-marbled paper cover, together with a front and a back sheet , and contained two manuscripts . The sheets, which were 215 millimeters high and 170 millimeters wide, had two different numbers . An older numbering starts with sheet 26 and ends with sheet 67. The sheet with the number 60 is missing. The newer numbering is continuous and includes page numbers 1 to 45. Pages 26 to 55 contain a treatise on the comet from 1590 by Tycho Brahe's assistant Longomontanus , which Longomontanus dedicated to his friend Johannes Eriksen. The dedication is dated July 18, 1600. The second manuscript is titled Nicolai Copernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus and includes pages 56 to 67. In 1878 Curtze published a briefly commented copy of the text in the first issue of the communications of the Coppernicus Association for Science and Art in Thorn .

A missing section of text, which contains most of Copernicus' lunar theory, was supplemented three years later by another manuscript find in Stockholm . A complete copy was discovered in 1881 in the library of the Stockholm Observatory , which is part of the Kungliga Biblioteket . It was bound with the Basel edition of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium and belonged to Johannes Hevelius . It has no signature .

In the early 1960s, William Persehouse Delisle Wightman (1899–1983) sifted through the 16th century scholarly writings that were kept in the library of the University of Aberdeen . In the second volume of the bibliography of these writings that he created and commented on, published in 1962, he noted a single page belonging to the Commentariolus . The sheet was contained in a volume from Duncan Liddels estate and was located between the pages of a Basel edition of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium with the signature "pi f521 Cop 2²" owned by King's College . Based on research by Jerzy Dobrzycki, it became clear three years later that this volume contained a third copy of the Commentariolus .

content

In his brief foreword , Copernicus first paid tribute to the theory of the homocentric spheres created by Eudoxus of Knidos and further developed by Callippos of Kyzikos , which made it possible to describe the irregular movements of the planets observed in the sky by means of regular circular movements . At the same time, however, he complained about their insufficient agreement with the observation results. The epicycle of Claudius Ptolemy certified Copernicus Although a good prediction of the position of the planets in the sky, but disagreed with the task of the regularity of planetary motion.

Copernicus based his considerations on how a perfectly uniform circular motion of the planets could be saved to the following "principles" listed after the preface:

- For all heavenly circles or spheres there is not just one center.

- The center of the earth is not the center of the world, but only that of gravity and the lunar orbit circle.

- All orbits surround the sun as if it were in the middle, and therefore the center of the world is close to the sun.

- The ratio of the distance between the sun and the earth to the height of the sky of the fixed stars is smaller than that of the radius of the earth to the distance to the sun, so that this is imperceptible compared to the height of the sky of the fixed stars.

- Everything that is visible in terms of movement in the fixed star sky is not seen in this way, but seen from the earth. The earth, with the elements adjacent to it, rotates once every day around its unchangeable poles. The fixed star sky remains immobile as the outermost sky.

- Everything that is visible to us in terms of movements in the sun is not created by itself, but by the earth and our orbit, with which we rotate around the sun like any other planet. And so the earth is carried there by multiple movements.

- What appears as retreat and advancement in the moving stars is not in itself like that, but seen from the earth. Their movement alone is sufficient for so many different appearances in the sky.

- Fritz Roßmann: The Commentariolus by Nicolaus Copernicus . 1947.

The first three principles give up the assumption of a common center of a circle for the description of the planetary revolutions , as it was demanded by the Greeks Eudoxus and Callippus, in favor of centers located near the sun. The assumption in principle number four explains why no changes can be perceived in the starry sky due to the annual Earth orbit - at that time no star parallax was measurable. Principles five through seven relate to the apparent movements caused by the movement of the earth .

The following main part consists of the following seven sections:

- De ordine orbium

on the arrangement of orbital circles - De motibus, qui circa Solem apparent

About the movements that are visible in the sun - Quod aequalitas motuum non ad aequinoctia, sed stellas fixas referatur

That the equality of movements does not have to be related to the equinoxes, but to the fixed stars - De Luna

Over the moon - De tribus superioribus, Saturno, Iove et Marte

About the three superiors: Saturn, Jupiter and Mars - De Venere

About Venus - De Mercurio

About Mercury

In it, Copernicus dealt with two basic subject areas. In the first three sections he described his views on the structure of the solar system , in particular the arrangement of the planetary orbits and the movements of the earth. In the remaining sections, Copernicus presented the main features of his planetary theory, but without going into mathematical details. He only worked this out in his major work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium , published in 1543 .

In About the arrangement of the orbit circles , Copernicus described the structure of the heavenly vault from the individual spheres. The most distant sphere is immobile and carries the fixed star sky. It encloses all other spheres. The spheres with Saturn , Jupiter , Mars , Earth and the orbiting Moon , Venus and Mercury follow from the outside in . The further out a planetary sphere is, the greater its orbital period . In the section on the movements that are visible in the sun , Copernicus explained the movement of the earth, which is composed of three components:

- The annual orbit around the sun.

- The daily rotation of the earth around its axis.

- The shift in the vernal equinox caused by the movement of the earth's axis .

The chapter That the equality of motions has to be related not to the equinoxes but to the fixed stars began by Copernicus with a comparison of the length of the determined by the astronomers Hipparchus of Nicea , al-Battānī , Claudius Ptolemaeus and Alfonso de Córdoba (1458? -?) tropical year . He attributed the different year lengths they determined to irregularities in the shift in the equinoxes over time. The description of the evenness of the duration of an earth's orbit should therefore be better based on the measurement of fixed star positions, since the orbital time thus determined is independent of the earth's precession . Copernicus proved the constancy of the sidereal year determined in this way by using the star Spica in the constellation Virgo to determine a duration of 365 days, 6 hours and about 10 minutes, as was already found in ancient Egypt. He recommended using this principle to determine the orbital times of the planets.

Copernicus offered the following explanations for the deviations of the observed planetary motion in relation to an assumed uniform circular motion of the planets, the so-called inequalities. The "first inequality", i.e. H. Copernicus explained the different speeds of movement of the planets on different orbital sections using two epicycles that move on the deferent sphere of the respective planet. The first epicyclic rotates in the opposite direction to the deferent sphere. The second epicyclic, moving on the first epicyclic, rotates in the same direction as the deferent sphere. In his main work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium , Copernicus replaced this double-epicyclic description with a mathematically equivalent description in which the epicyclic is eccentrically shifted from the center. Copernicus was able to easily deduce the "second inequality", which refers to the fact that planets carry out loop movements, during which standstills, reversals and fluctuations in brightness occur, from the arrangement of the spheres and their rotational speeds, in which the faster planet overtakes the slower one. To explain further observation results, such as the change in the ecliptical latitude of a planet, Copernicus had to introduce further uniformly rotating auxiliary circles.

At the end of the Commentariolus , Copernicus summarized what he had achieved:

“According to this, the orbit of Mercury needs a combination of seven circles, Venus needs five, Earth three and the moon orbiting around it four, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn finally five each. So 34 circles are enough to explain the whole structure of the world, the whole round dance of the stars! "

distribution

Nothing certain is known about the spread of the Commentariolus during Copernicus' lifetime and its influence on contemporary astronomy. The Copernicus researcher Owen Gingerich takes the view that copies of the Commentariolus circulated among a few confidants of Copernicus. The circulating copies of the Commentariolus may have contributed to Copernicus being invited to express his opinion on the upcoming calendar reform at the Fifth Lateran Council .

In Tycho Brahe's work Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata (German: Introduction to Renewed Astronomy ) , published in 1602, there is a brief reference to the Commentariolus : “... or you can relate this to the annual cycle of the sun in the same way as Copernicus did in his little treatise on the hypotheses he has put forward. This was given to me as a manuscript from his time in Regensburg by the highly esteemed Doctor Thaddeus Hagecius, who is a close friend of mine. I myself later told some other German mathematicians what I am bringing to mind here so that those into whose hands this document has come will know where it originated from. "(" ... Copernicus in Tractatulo quodam de Hypothesibus a se constitutis, quem mihi Ratisbonae aliquando manuscriptum impertijt Clarissimus vir D. Thaddaeus Hagecius… ego vero eundem postea alijs quibusdam in Germania Mathematicis communicaui… ".)

Tycho Brahe received his copy in 1575 as a gift from Thaddaeus Hagecius on the occasion of the coronation celebrations of Rudolf II in Regensburg . Hagecius' copy possibly goes back to Georg Joachim Rheticus , as Rheticus left parts of his library to him. When Longomontanus said goodbye to Tycho Brahe in Benátky nad Jizerou , he gave his friend Johannes Eriksen a copy of the Commentariolus . This finally came to the Viennese court library with Brahe's estate.

One of the copies made by Brahe and sent to Germany went to Heinrich Brucaeus in Rostock , with whom Brahe studied from 1566 to 1568. Duncan Liddel was enrolled in Rostock in 1585, who on November 2, 1585 completed his copy of the Commentariolus , which was later found in Aberdeen. Although the copy found in Stockholm is similar to Liddel's copy, it is still unclear how it got to Stockholm.

Dating

Maximilian Curtze dates the Commentariolus in his publication from 1878 to the beginning of the 1530s. In the early 1920s, the Polish Copernicus researcher Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer (1855–1929) was able to better pinpoint the time. In the Kraków Jagiellonian Library he found a library directory under manuscript number 5572, which the Kraków geographer and historian Matthias von Miechow (1457–1523) had created on May 1, 1514. In it Miechow wrote: "Likewise a Sexternus of the theory, which says that the earth moves, but the sun rests." ("Item sexternus theorice asserentis terram moveri, Solem vero quiescere".) This six-layer folio font (Sexternus) is used by the Research interpreted as a reference to the Commentariolus . When he published his find in 1924, Birkenmajer suspected that Copernicus gave a copy of his Commentariolus to his friend, the Cracow Canon Bernard Wapowski , in 1509 , who later passed the copy on to Matthias von Miechow.

In 1973, Noel Swerdlow investigated whether the Commentariolus could be dated from Copernicus by means of documented astronomical observations, but had to deny this. The American Copernicus researcher Edward Rosen (1906–1985), who shortly before his death translated the third volume of Copernicus' works published by the Polish Academy of Sciences into English, concluded from the available findings that the Commentariolus was written in the second half of 1508 at the earliest and in early 1514 at the latest. The German Kopernikus biographer and collaborator on the Nicolaus Copernicus Complete Edition , the philosopher Jürgen Hamel , sees the time of Copernicus' stay in Heilsberg from the beginning of 1504 to mid-1510 as the period for the development of the ideas written down in the Commentariolus and the writing down itself . Martin Carrier mentions the most likely point in time as the end of Copernicus' life in Heilsberg, i.e. around 1509.

Modern reception

After the publication of the original Latin text of the second manuscript, Maximilian Curtze published a text comparison of the two previously known manuscripts in 1882 . Leopold Prowe used this text comparison and both manuscripts in 1884 for the Latin text printed in the second volume of his Copernicus biography. The first translation from Latin was published in 1899 by Adolf Müller in the magazine for the history and antiquity of Warmia . Edward Rosen wrote the first English translation, first published in Osiris magazine in 1937 and reprinted two years later in his book Three Copernican Treatises . Several unaltered reprints of this translation followed. A second German translation based on the original manuscripts was made in 1948 by Fritz Rossmann. A reprint appeared in 1966.

Noel Swerdlow's English translation from 1973 is extensively commented on and provided with numerous explanatory illustrations. A critical edition of the Latin text combined with a new German translation appeared in the fourth volume of the Nicolaus Copernicus Complete Edition in 2019 .

proof

literature

Facsimiles

- [ Facsimile of the Aberdeen manuscript ]: In: Pawel Czartoryski (Ed.): Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 4: The Manuscripts of Nicholas Copernicus' Minor Works Facsimiles. Warsaw / Krakau 1992, ISBN 83-01-10562-3 , pp. 208-217.

- [ Facsimile of the Stockholm manuscript ]: In: Pawel Czartoryski (Ed.): Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 4: The Manuscripts of Nicholas Copernicus' Minor Works Facsimiles. Warsaw / Krakau 1992, ISBN 83-01-10562-3 , pp. 218-233.

- [ Facsimile of the Vienna manuscript ]: In: Pawel Czartoryski (Ed.): Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 4: The Manuscripts of Nicholas Copernicus' Minor Works Facsimiles. Warsaw / Krakau 1992, ISBN 83-01-10562-3 , pp. 234-252.

Latin text editions

- Maximilian Curtze: The "Commentariolus" of Coppernicus on his book "De revolutionibus" . In: Communications of the Coppernicus Association for Science and Art in Thorn . Issue 1, Leipzig 1878, pp. 1–17.

- Arvid Lindhagen: Nicolai Coppernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus: Manuscriptum Stockholmiense, in Bibliotheca Reg. Acad. Scient. Suec. servatum . In: Bihang till Kungliga Svenska Vetenskaps-Akademiens Handlingar . Volume 6, Part 12, Stockholm 1881, pp. 1-16, online .

- Leopold Prowe : Nicolaus Coppernicus . Volume 2, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1884, pp. 184-202, online .

Translations

- Pawel Czartoryski (ed.): Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 3: Minor Works. Warsaw / Krakau 1985, ISBN 83-01-06320-3 , pp. 75–126.

- Adolf Müller: Nicolai Coppernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus . In: Journal for the history and antiquity of Warmia . Volume 12, 1899, pp. 359-382.

- Edward Rosen : The Commentariolus of Copernicus . In: Osiris . Volume 3, 1937, pp. 123-141, JSTOR 301584 .

- Edward Rosen: Three Copernican Treatises . New York 1939. (Mineola 2004 reissue, ISBN 0-486-43605-5 , pp. 55-90.)

- Fritz Roßmann: The Commentariolus by Nicolaus Copernicus . In: Natural Sciences . Volume 34, number 3, 1947, pp. 65-69, doi: 10.1007 / BF00663113 .

- Fritz Rossmann (Hrsg.): First draft of his world system as well as a discussion between Johannes Kepler and Aristotle about the movement of the earth . Rinn, Munich 1948 (reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1986).

- Noel M. Swerdlow: The Derivation and First Draft of Copernicus's Planetary Theory: A Translation of the Commentariolus with Commentary . In: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society . Volume 117, Number 6, 1973, pp. 423-512, JSTOR 986461 .

Others

- Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer: Stromata Copernicana: Studja, poszukiwania i materjały biograficzne . Polska Akademia Umiejętności, Kraków 1924, pp. 201–205.

- Martin Carrier : Nicolaus Copernicus. Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-47577-9 , pp. 67-74.

- Walter Salvator Contro, Johannes Feitzinger , Rolf Hartmann, Friedrich W. Ihloff, Hans-Georg Märtl, Friedemann Rex, Matthias Schramm, Horst Zehe: On the kinematics of planetary motion in Copernicus' Commentariolus . In: Archive for History of Exact Sciences . Volume 6, number 5, 1970, pp. 360-371, doi: 10.1007 / BF00329817 .

- Maximilian Curtze: Supplements to the Inedita Coppernicana in the first booklet of these "communications" . In: Communications of the Coppernicus Association for Science and Art in Thorn . Issue 1, Thorn 1882, pp. 3-9.

- Jerzy Dobrzycki: The Aberdeen Copy of Copernicus's Commentariolus . In: Journal for the History of Astronomy . Volume 4, 1973, pp. 124-127, bibcode : 1973JHA ..... 4..124D Online.

- Jerzy Dobrzycki, William Persehouse Delisle Wightman: The Commentariolus of Copernicus . In: Nature . Volume 208, 1965, p. 1263, doi: 10.1038 / 2081263b0 .

- Jerzy Dobrzycki, Lech Szczucki: On the Transmission of Copernicus' Commentariolus in the Sixteenth Century . In: Journal for the History of Astronomy . Volume 20, Number 1, 1989, pp. 25-28, bibcode : 1989JHA .... 20 ... 25D Online.

- Jürgen Hamel : Nicolaus Copernicus. Life, work and effect . Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-86025-307-7 , pp. 144-157.

- Leopold Prowe: Nicolaus Coppernicus . Volume 1, Part 2, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1883, pp. 282-292, online .

- Alfred Romer: The Welcoming of Copernicus's De revolutionibus: The Commentariolus and its Reception . In: Physics in Perspective . Volume 1, Number 2, 1999, pp. 157-183, doi: 10.1007 / s000160050014

- Edward Rosen: Copernicus' Axioms . In: Centaurus . Volume 20, Number 1, 1976, pp. 44-49, doi: 10.1111 / j.1600-0498.1976.tb00216.x .

- Noel Swerdlow : A Summary of the Derivation of the Parameters in the Commentariolus from the Alfonsine Tables with an Appendix on the Length of the Tropical Year in Abraham Zacuto's Almanach Perpetuum . In: Centaurus . Volume 21, Numbers 3-4, 1977, pp. 201-213, doi: 10.1111 / j.1600-0498.1977.tb00353.x

- William Persehouse Delisle Wightman: Science and the Renaissance: An annotated bibliography of the 16th-century books relating to the sciences in the library of the University of Aberdeen . Volume 2, Edinburgh 1962, p. 67.

Individual evidence

- ^ Maximilian Curtze: The "Commentariolus" of Coppernicus on his book "De revolutionibus" . 1878, pp. 1-2.

- ^ Jerzy Dobrzycki: The Aberdeen Copy of Copernicus's Commentariolus . 1973, p. 124.

- ^ Arvid Lindhagen: Nicolai Coppernici de hypothesibus motuum coelestium a se constitutis commentariolus: Manuscriptum Stockholmiense, in Bibliotheca Reg. Acad. Scient. Suec. servatum . 1881, pp. 1-16.

- ↑ William Persehouse Delisle Wightman: Science and the Renaissance: An annotated bibliography of the 16th-century books Relating to the sciences in the library of the University of Aberdeen . Volume 2, Edinburgh 1962, p. 67.

- ↑ Jerzy Dobrzycki, William Persehouse Delisle Wightman: The Commentariolus of Copernicus . 1965, p. 1263.

- ^ Jerzy Dobrzycki: The Aberdeen Copy of Copernicus's Commentariolus . 1973.

- ^ Noel M. Swerdlow: The Derivation and first draft of Copernicus's Planetary Theory, a translation of the Commentariolus with commentary . 1973.

- ^ Fritz Roßmann: The Commentariolus by Nikolaus Kopernikus . 1947, p. 66.

- ↑ Jose Chabas: Astronomy for the Court in the Early Sixteenth Century . In: Archive for History of Exact Sciences . Volume 58, Number 3, pp. 183-217, doi: 10.1007 / s00407-003-0073-2 .

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Nicolaus Copernicus. Life, work and effect . 1994, p. 145.

- ^ Leopold Prowe: Nicolaus Coppernicus . Volume 1, Part 2, 1883, p. 292.

- ^ Owen Gingerich: The book nobody read: Chasing the revolutions of Nicolaus Copernicus . William Heinemann, 2004, ISBN 0-434-01315-3 , p. 31.

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Nicolaus Copernicus. Life, work and effect . 1994, p. 148.

- ^ Fritz Roßmann: The Commentariolus by Nikolaus Kopernikus . 1947, p. 68

- ^ Johan Ludvig Emil Dreyer (Ed.): Tycho Brahe: Opera omnia . Volume 2, 1913, p. 428, line 34, online .

- ^ Johan Ludvig Emil Dreyer: Tycho Brahe: A picture of scientific life and work in the sixteenth century . Adam & Charles Black, Edinburgh 1890, p. 83, online .

- ↑ Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 3, p. 78.

- ↑ Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 3. p. 77.

- ↑ Jerzy Dobrzycki, Lech Szczucki: On the Transmission of Copernicus' Commentariolus in the Sixteenth Century . 1989, p. 25

- ^ Maximilian Curtze: The "Commentariolus" of Coppernicus on his book "De revolutionibus" . 1878, p. 4.

- ↑ Nicolaus Copernicus Complete Edition . Volume 6, Part 2, p. 138.

- ^ Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer: Stromata Copernicana , 1924, p. 201.

- ^ Ludwik Antoni Birkenmajer: Stromata Copernicana . 1924, pp. 201-205.

- ^ Noel M. Swerdlow: The Derivation and First Draft of Copernicus's Planetary Theory: A Translation of the Commentariolus with Commentary . 1973, pp. 429-431.

- ↑ Nicholas Copernicus. Complete Works . Volume 3, p. 80.

- ↑ Jürgen Hamel: Nicolaus Copernicus. Life, work and effect . 1994, p. 146.

- ↑ Martin Carrier: Nikolaus Kopernikus. 2001, p. 67.

- ↑ Maximilian Curtze: Supplements to the Inedita Coppernicana in the first booklet of these "communications" . 1882, pp. 3-9.

- ^ Leopold Prowe: Nicolaus Coppernicus . Volume 2, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1884, pp. 184-202.

- ^ Noel M. Swerdlow: The Derivation and First Draft of Copernicus's Planetary Theory: A Translation of the Commentariolus with Commentary . 1973, pp. 431-433.