Corporate social responsibility

The term Corporate Social Responsibility ( CSR ) or Corporate Social Responsibility (often referred to as Corporate Social Responsibility called) describes the voluntary contribution of business to sustainable development , which goes beyond the legal requirements. CSR stands for responsible entrepreneurial action in actual business activity (market), through ecologically relevant aspects (environment) to relationships with employees (workplace) and the exchange with the relevant stakeholders .

Definition and facets of CSR

definition

There is no generally accepted definition of the term Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Especially in Anglo-American usage, but increasingly also in German-speaking countries, related terms such as corporate responsibility or corporate citizenship are also used in the discussion about the role and responsibility of companies in society . While the terms CSR and Corporate Citizenship (CC) are often used synonymously in business practice, a clear position on the relationship between the two concepts has emerged in German-language literature:

- Corporate Citizenship (CC) therefore only represents a part of the social responsibility of companies and describes the commitment of companies to the solution of social problems in the local environment of the company, which goes beyond the actual business activity. Thus, CC is essentially reduced to sponsoring , donations and foundations.

- In Europe, the CSR definition anchored in the European Commission's Green Paper has established itself as a common understanding:

"Concept that serves as a basis for companies to voluntarily integrate social and environmental concerns into their business activities and into their interactions with stakeholders."

The European Commission's definition names social and environmental concerns as two central points for CSR. If you expand this to include economic issues, you get the three dimensions of sustainability (see also the three-pillar model ). In a more recent document (COM (2011) 681 final) the CSR definition is shortened somewhat:

"The responsibility of companies for their impact on society"

and should now be more in line with international definitions.

In the modern understanding of CSR is increasingly seen as a holistic construed, all dimensions of sustainability integrating corporate concept that all "social, environmental and economic contributions of a company for voluntary assumption of social responsibility, the legal on compliance with regulations (compliance) go." Includes.

To justify the need to implement CSR in companies, a basic distinction is made between two approaches: the normative and the economically motivated approach. The normative approach regards the company as part of society and is therefore also called the corporate citizenship approach. The company claims non-monetary services from society, such as B. Infrastructure, security, education and social systems. In return, companies are expected to take social responsibility in return. The normative approach thus justifies the regulatory pressure from governments and transnational institutions to demand social responsibility from companies.

The economically motivated approach, on the other hand, tries to justify the motivation to implement CSR intrinsically. The aim is to prove that a voluntary, non-normative implementation is associated with an increase in benefits for the company itself. This increase in benefit is justified with the creation and evaluation of intangible assets , such as B. Reputation , trust , employee motivation and customer satisfaction .

However, the principle of voluntariness also raises the question of the real motives for CSR. In most cases it can be assumed that companies are not acting out of altruism alone - they are also pursuing economic goals - such as increasing sales and profits. The increased focus on CSR is supported by the knowledge that corporate responsibility contributes to increasing corporate success in the medium and long term (business case). The possibility to use CSR as an advertising measure and to present oneself as a socially committed company appears to be an important motivation. This is considered legitimate as long as the actual sustainability performance is in line with the communicated commitment. However, if excessive exaggerations, half-truths or individual aspects beyond an unsustainable core business are publicly highlighted (often with a lot of PR effort ), this is called greenwashing, for example .

After a five-year process, the ISO standard 26000 “Guidance on Social Responsibility” was adopted in September 2010 . The non-certifiable standard is a guideline to raise awareness of social responsibility and to promote uniform terminology. The guideline incorporates already existing approaches to ecological and social responsibility ( ILO core labor standards, GRI ( Global Reporting Initiative ), Global Compact etc.) and contains many examples of good CSR practice ( best practices ).

Structuring according to areas of responsibility

CSR activities can be structured in different ways. According to Hiß, a possible assignment takes place via the various areas of responsibility of a company.

Inner area of responsibility

The internal area of responsibility describes the company's obligations towards the market (profitability) and towards the law. This area can only be assigned to CSR if it is also voluntary. This is the case, for example, when laws are strictly adhered to, although they are usually not enforced in a production country, or when relocation would be easy. The company's profit making also falls under this area of responsibility. In the public debate, the opinion is often expressed that CSR implies a general renunciation of corporate profits. This is countered by the fact that companies in competition cannot afford to generally forego profits in the name of CSR and thus accept competitive disadvantages. There are of course ways of making profit that are incompatible with CSR (such as neglecting safety standards, exploiting employees or violating human rights). Accordingly, the question of the relationship between CSR and profit making must be viewed in a differentiated manner. First of all, it should be noted that entrepreneurial profit is necessary and socially desirable in the market economy system. However, a distinction must be made between responsible and irresponsible profit making. Companies have a responsibility to refrain from making short-term profits at the expense of third parties. Such a waiver is in the enlightened self-interest of companies, as it allows certain assets (such as integrity or credibility) to be built up that are important for entrepreneurial cooperation and social acceptance ("license to operate"). This shows that such a waiver of short-term profit generation at the expense of third parties is an investment in the conditions of long-term business success. On the one hand, CSR requires investments, but on the other hand it has economic effects on success (increase in financial performance, cost reduction) and non-economic effects on success (development of a positive reputation, risk avoidance, product and process innovations).

Medium area of responsibility

The middle area of responsibility comprises the company's value chain. Self-commitments with regard to compliance with labor and environmental standards, but also supply chain management , fall into this area. The stakeholder dialogue appears to be essential for successful CSR. Stakeholders are people or institutions who have a legitimate interest in the activities of a company or are affected by its actions. Important stakeholders are equity and debt capital providers, employees and trade unions, customers and suppliers, local residents, consumer and environmental protection associations, government organizations, the media and the general public.

In the context of CSR, the dialogue with stakeholders is so important because they are the ones to whom corporate responsibility must relate. In the case of larger, listed companies in particular, CSR has become an important prerequisite for good rating results and access to certain funds or capital market segments.

External responsibility

All activities that are not covered by the two aforementioned areas of responsibility are located at this level. This includes the much-noticed aspects of CSR such as donations ( corporate giving ), sponsoring or the release of employees for social activities ( corporate volunteering ). The external area of responsibility corresponds to the understanding of corporate citizenship .

Models of CSR

Carroll's four-step pyramid

Archie B. Carroll divides corporate social responsibility into four levels:

- Economic responsibility states that a company must at least cover its costs.

- Legal responsibility states that a company must not engage in illegal activities and must comply with the law.

- Ethical responsibility describes the requirement on the company to act fairly and ethically beyond the existing laws

- The fourth level is called philanthropic responsibility, it describes charitable social engagement that goes beyond social expectations.

A company has to adhere to the first two levels, apart from exceptional cases, in order to survive (socially challenged). The third level of moral action is necessary in order to be socially accepted, but it is not absolutely necessary (socially expected). The fourth level is purely voluntary, but socially desirable. In principle, CSR encompasses all four levels. However, the four-step pyramid does not differentiate according to ecological or social aspects; there is also the problem of being able to derive common expectations from a modern society.

Two dimensions according to Quazi and O'Brien

Quazi and O'Brien characterize four perspectives of CSR, which are plotted in a two-dimensional diagram (see illustration). The following statements are approximately consistent:

- The classic view corresponds to Carroll's economic level.

- The socio-economic level corresponds to a mixture of the legal and the ethical level according to Carroll.

- The modern view corresponds to the ethical level according to Carroll with influences of the stakeholder theory.

- The philanthropic perspectives from both models also correspond.

Core areas according to Carroll and Schwartz

Another model comes from Archie B. Carroll and Mark S. Schwartz. Here, CSR is divided into three core areas: economic, ethical and legal responsibility. These core areas intersect with each other, resulting in seven possible categories of CSR (see figure). In this presentation, the ecological dimension is classified under the ethical one.

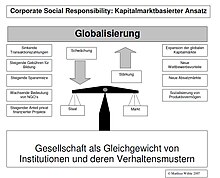

Wühle capital market model

According to Wühle, the reasons for the growing importance of corporate social responsibility lie in the social and socio-economic changes in recent years, which have led to distortions in the balance of power between government, civil society and the market. The growing inability of the state to provide social benefits meets a capital market that makes it interesting for companies to offer these benefits. Because globalization is changing the balance between state and market to the disadvantage of the state, there is increasing market demand for social services, such as B. education, culture or security, whereby the state withdraws more and more from the supply side and leaves this to the market. Corporate social responsibility thus becomes a product of the capital market.

Historical background

Even the ancient authors dealt with the question of sustainable management. Aristotle already established in the first book of politics (Πολιτικά) that economic activity is not a proper and in itself purposeful sphere, but a means to a good and right life:

"[...] Now it is clear that the activity of property management ( οἰκονομία ) directs its efforts to a greater degree on people than on inanimate property and more on virtue ( ἀρετή ) of people than on the accumulation of property."

The model of the honorable merchant has existed in Europe since the Middle Ages, imposing the observance of certain behavioral norms on individual merchants, which among other things served the social balance in the cities. An outstanding example of socially committed entrepreneurship from the time of early capitalism is the Fuggerei in Augsburg , which still exists today . In the industrialization of the 18th century, the honorable merchants of the European bourgeoisie became entrepreneurs, for whom social engagement was also a matter of course. They acted as patrons and donors and took care of improving the working and living conditions of their employees, for example by building houses.

The concept of entrepreneurial social commitment has received sharp criticism from the Marxist- oriented labor movement since the 19th century. It can be summed up with a line from the German version of the second stanza of the battle song Die Internationale : "Empty word: the rich man's duty!"

The term sustainability comes from forestry and was first formulated in 1713 by the Saxon chief miner Hans Carl von Carlowitz .

The scientific study of the topic of CSR has its roots in the USA, where a discussion about the content and scope of corporate responsibility has apparently only been taking place since the 1950s. One of the first publications on the subject was Howard R. Bowen's Social Responsibilities of the Businessman (1953). In it he took the view that corporate social responsibility should be based on social expectations and values. Since the companies are making use of social rights, they also have to assume corresponding obligations. From the 1970s, the company was viewed as an actor. It was now of the opinion that companies should not only respond to society's expectations, but also actively shape their commitment. From the 1970s onwards, it was increasingly recognized that stakeholders, as those affected by corporate activities, on the one hand play an indispensable role for the existence of companies and on the other hand benefit relationships exist between stakeholders and companies (cf. Cyert and March 1963). The inclusion of the stakeholder approach in strategic management is to be seen as a reaction to the prevailing shareholder value idea and laid the foundation for today's CSR concepts.

The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 and commissioned the report The Limits to Growth , which was published in 1972 with great media impact. Since 1969, the UN and its Secretary General U Thant have also turned their attention to the critical tendencies of the globalized economy and called for a new form of responsible management. The idea of environmental protection has been developing since the 1970s, from which the idea of sustainable development emerged . Since the 1990s, both ideas - CSR and environmental protection / sustainability - have merged into a single unit and a holistic understanding of CSR.

In Europe, however, the CSR discussion only developed later. This was probably due, on the one hand, to the more pronounced social security systems compared to the USA, and, on the other hand, to the traditional anchoring of a sense of responsibility in European companies.

In 2001 the Green Paper European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility was published in the European Union , in which the European Union first dealt with the subject. In 2002 the “ European Multi-Stakeholder Forum on CSR ” (EMS Forum) was founded. In the years 2011 to 2014, as part of the implementation of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategy 2011–2014, the European Commission showed what had been achieved and what still needs to be done in the future for implementation and beyond. The function and role of the European Commission in implementation and support is shown. There is also a public consultation launched by the European Commission on the subject of The European Commission's strategy on CSR 2011–2014: achievements, shortcomings and future challenges , which until August 15, 2014, invited EU citizens to participate in discussions and contributions. This CSR strategy is intended to strengthen the implementation of the principles of corporate social responsibility in the European Union. The consultation covers eight areas. The results of the consultation will be compiled in a report by the European Commission. These results and those of a “multi-stakeholder forum” will be evaluated by November 2014 and then form the basis for the European Commission's CSR policy after 2014. On April 16, 2013, the European Commission presented a proposal for a directive. As a result, companies in the public interest are to be obliged from 2017 to largely disclose their corporate social responsibility (CSR) concepts. The Council of Ministers approved on 29 September 2014, a compromise text on the draft directive COM (2013) 207 of 16 April, 2013.

The Austrian Standards Institute ( Austrian Standards ) is a pioneer in the German-speaking area with regard to standardization around the topic. There is a set of rules (ONR 192500: 2011) regarding the social responsibility of organizations. This set of rules is not only aimed at economically managed companies, but also refers generally to “organizations” and also includes NGOs and other organizations. In addition, there is a standard that relates to services from the management consulting area. This concerns the S2502: 2009 - Consulting services on the social responsibility of organizations. Here, too, not only with regard to business companies, but all kinds of organizations.

Implementation by the company

Due to changed framework conditions (improved information and communication technology, growing number of critical non-governmental organizations and thus possibly changing attitudes among consumers and the general public), companies are increasingly dealing with CSR. Otherwise, they would run the risk of losing the society's required “authority to act”. As a reaction to the problem, the number of specialized consulting agencies and CSR departments is growing. While charitable activities used to be more dependent on the inclinations of the management staff, today they are increasingly the subject of strategic planning and are more closely coordinated with other public relations activities .

Corresponding concepts are:

- Integration into the core business: In the medium term, it appears indispensable for credible CSR to achieve the actual strategic anchoring in the core business and the realignment of the business model instead of selective activities and secondary projects. This would e.g. For a bank, for example, this means looking at the sustainability effects of financial products or developing microfinance services that enable disadvantaged sections of the population to develop self-sustaining economic developments.

- In order to find a common approach to the topic of CSR, companies form networks . Examples of well-known networks are: econsense, companies: Aktiv im Gemeinwesen, CSR Europe and the UN Global Compact .

- Base of the Pyramid : This concept (the base of the pyramid, based on the income pyramid) describes the inclusion of the poorest parts of the population in the regular economic cycle. When combined with CSR concepts, both entrepreneurial value creation and long-term poverty reduction should be promoted. Possible starting points here is a code of conduct with social standards, a ban on child labor, minimum wages and the like. This can also be passed on to the supplier companies via sustainable supply chain management .

- Cultural diversity: Increasing globalization is increasingly ensuring that production sites are relocated to emerging and developing countries. In these, the social legislation and social standards are generally lower than in the industrialized nations. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and interested consumer groups, however, expect multinational corporations to produce according to a relatively uniform social standard worldwide. It may therefore be necessary to pursue CSR activities that go beyond national legislation and are tailored to the cultural characteristics of the country in question. But also within a state, aspects of cultural diversity, e.g. B. promote through diversity management.

- To increase the credibility and legitimacy of companies, they can create and use binding quality seals, environmental and social standards. Examples of this are the EMAS regulation , SA 8000 , ISO 14001 or quality seals such as FSC , MSC or the Blue Angel .

- Cooperation with stakeholders, especially with non-governmental organizations , can be an important support for companies in the planning and execution of CSR activities and can also increase their credibility.

- The introduction of binding design guidelines to reduce material and energy requirements and to avoid waste and emissions can improve the environmental balance.

- Corporate volunteering : Describes a concept in which employees are released for part of their working hours in order to pursue a social or ecological commitment. On the one hand, this activity should have a social benefit and, on the other hand, it should promote the development of social skills among employees and their ties to the company. The narrow majority of a sample of companies surveyed by Apriori Business Solutions 2009 at least implicitly expects their executives to be socially committed in associations, foundations, etc. This should manifest themselves in social competence and a sense of responsibility, especially among employees in management careers. At the same time, the companies hope that this will have a positive effect on their own company.

In order to simultaneously promote the motivation of the employees, CSR programs are preferably carried out at the locations of the respective company.

Implementation along the supply chain

Incidents such as the building collapse in Savar Upazila (2013), the more than 1,000 lives has demanded in the textile sector have the role of the supply chain (supply chain) provided rather than just a single company as a design object of CSR to the fore. Supply chain management approaches are therefore increasingly used to strengthen CSR. Wieland and Handfield (2013) propose three sets of measures to ensure CSR along the supply chain. An auditing of products and suppliers must take place, but this auditing must also include suppliers of suppliers. In addition, transparency must be increased along the entire supply chain, with smart technologies offering new potential. Finally, CSR can be improved through cooperation with local partners, with other companies in the industry and with universities.

Legal implementation

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union issued Directive 2014/95 / EU on October 22, 2014. It is aimed at all member states and calls for their regulations to be implemented in national law by December 6, 2016. In Germany, the implementation was delayed with the CSR Directive Implementation Act that came into force on April 19, 2017 .

criticism

Corporate social responsibility is also exposed to criticism. This is essentially based on the fact that companies (especially listed companies) operate according to the criteria of profit maximization and that social or ecological aspects play no or only a subordinate role for them. Many companies would therefore only pursue corporate social responsibility for economic reasons, and in such a way that they achieve a maximum positive effect for themselves with minimal costs. So there are doubts about the sincerity of the motives for a commitment in terms of CSR. In the opinion of the critics, such companies do not implement CSR activities “for the sake of the matter”, but for one or more of the following reasons:

- Improvement of your own image

- A company implements CSR activities and highlights them (for example in its advertising) as one of its outstanding features. The goal is to improve the company's reputation among the population (and often an associated increase in profits). In such cases, the cost of advertising can exceed the cost of implementing CSR activities many times over. Criticism is especially practiced in such companies, by the CSR activity apart by their other actions environmental or social not sustainable. With regard to ecological sustainability, one speaks of greenwashing in such a context .

- Prevention of the creation of laws

- Due to the increasing global demand for ecologically and socially sustainably produced goods and the growing expectation that society places on companies to conduct business in an ethically correct manner, there is also a growing likelihood that more and more countries will introduce laws that force companies to act in this way. In the opinion of the critics, CSR is therefore implemented by some companies in order to prevent the creation of such laws, as these would involve much higher costs for the companies than if they volunteered. Critics compare this to a sale of indulgences , a message from companies to politicians and citizens: "We take care of it, we don't need any rules and you consumers can shop with us in peace."

- Avoidance of follow-up costs from breakdowns and accidents

- Environmentally and socially unsustainable action can lead to breakdowns, accidents or other misfortunes, the consequences of which are associated with considerable costs for the responsible company, which by far exceed the costs saved. For this reason, CSR activities for such companies also make sense from a financial point of view and, according to the critics, are only carried out for financial reasons. Examples of incidents that resulted in the implementation of CSR are the Exxon Valdez tanker disaster in 1989, or the recall of lead-contaminated toys from Mattel in 2007.

See also

- Social entrepreneurship

- Sustainability management

- Corporate Citizenship

- Corporate volunteering

- Corporate donations

- TRIGOS price

- UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

literature

- Edward Freeman, Alexander Moutchnik : Stakeholder management and CSR: questions and answers. In: UmweltWirtschaftsForum. Springer-Verlag, Volume 21, No. 1, 2013. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00550-013-0266-3

Essays

- Alexander Bassen, Sarah Jastram, Katrin Meyer: Corporate Social Responsibility. An explanation of the term. In: Journal for Economic and Business Ethics. Vol. 6, No. 2, 2005. Rainer Hampp Verlag, Mering, ISSN 1439-880X , pp. 231-236.

- Frank Czymmek, Ines Freier, Charlotte Hesselbarth, Alexandro Kleine: Corporate Social Responsibility. In: Annett Baumast, Jens Pape (Hrsg.): Corporate environmental management in the 21st century. 4th edition. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, pp. 241-254.

- Ursula Hansen, Ulf Schrader: Corporate Social Responsibility as a current topic in business administration. In: Business Administration. Vol. 65, No. 4, pp. 373-395.

- Daniel Klink: The Honorable Merchant - The original model of business administration and individual basis for CSR research. In: Joachim Schwalbach (Ed.): Corporate Social Responsibility. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft - Journal of Business Economics. Special Issue 3. Gabler, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-1044-8 , pp. 57-79.

- Marina Hoffmann, Frank Maaß: Corporate Social Responsibility as a Success Factor in a Stakeholder-Related Management Strategy? Results of an empirical study. In: Institute for SME Research Bonn (Ed.): Yearbook on SME Research 2008 . Gabler, Wiesbaden 2009, ISBN 978-3-8349-1609-9 , pp. 1-51. (Writings on SME Research, No. 116)

Monographs

- Andreas Schneider, Rene Schmidpeter, (Eds.) Corporate Social Responsibility - responsible corporate management in theory and practice, Springer-Gabler-Verlag 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-25398-0 .

- Stefanie Hiß : Why do companies take on social responsibility? A sociological attempt at explanation . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-593-38187-7 .

- Nick Lin-Hi: A Corporate Responsibility Theory: Linking Profit Making and Social Interests. Erich-Schmidt-Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-503-11478-8 .

- Thomas Loew, Kathrin Ankele, Sabine Braun: Significance of the international CSR discussion for sustainability and the resulting requirements for companies with a focus on reporting. Münster / Berlin 2004.

- Lothar Rieth: Global Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility. What influence do the UN Global Compact, the Global Reporting Initiative and the OECD guidelines have on the CSR engagement of German companies? Budrich UniPress, Opladen 2009, ISBN 978-3-940755-31-5 .

- Jan Jonker, Wolfgang Stark, Stefan Tewes: Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development. Introduction, strategy and glossary. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-14688-6 .

Web links

- Corporate values CSR program of the German federal government

- Information on the CSR activities of the Council for Sustainable Development , Council for Sustainable Development

- Corporate Social Responsibility (PDF; 318 kB), documentation of the results of a company survey by the Bertelsmann Foundation from 2005

- UmweltDialog, independent CSR news service since 2003

- Study ( memento of March 12, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) by the Institute for Ecological Economic Research on the CSR discussion and requirements for companies

- CSR and small and medium-sized businesses. ( Memento of January 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) European Commission

- Eurobarometer survey How Businesses Affect Our Society: The Citizens' Perspective (published 2013).

- csrgermany.de ( Companies bear responsibility - initiative of the leading associations BDA , BDI , DIHK , ZDH ) (February 9, 2013)

Footnotes

- ↑ F. Dubielzig, S. Schaltegger : Corporate Social Responsibility. In: M. Althaus, M. Geffken, S. Rawe (eds.): Handlexikon Public Affairs (PDF; 147 kB) Lit Verlag, Münster 2005, pp. 240–243.

- ↑ Thomas Loew, Kathrin Ankele, Sabine Braun: Significance of the international CSR discussion for sustainability and the resulting requirements for companies with a focus on reporting. Münster / Berlin 2004.

- ↑ Green Paper on a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility. (PDF; 198 kB) COM (2001) 366 final, Brussels 2001.

- ↑ Green Paper on a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility. COM (2001) 366 final, Brussels 2001, p. 29 ff.

- ↑ COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS (PDF) .

- ^ Heribert Meffert , Matthias Münstermann : Corporate Social Responsibility in Science and Practice: An Inventory. Working paper No. 186, Scientific Society for Marketing and Management V., Münster 2005, p. 20 f.

- ↑ Oliver Herchen: Corporate Social Responsibility. How companies deal with their ethical responsibility. Norderstedt 2007, ISBN 978-3-8370-0262-1 , p. 25 f.

- ↑ Matthias Wühle: With CSR to corporate success . Social responsibility as a value creation factor. Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-0259-0 , p. 6ff.

- ↑ Matthias Wühle: With CSR to corporate success . Social responsibility as a value creation factor. Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-0259-0 , p. 14ff.

- ↑ ISO 26000: 2010.

- ↑ Stefanie Hiß: Why do companies take on social responsibility - a sociological attempt at explanation. Frankfurt am Main 2006: Campus

- ↑ Martin Müller, Stefan Schaltegger: Corporate Social Responsibility: Trend or Fad. Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-86581-053-3 , p. 21 f.

- ↑ Nick Lin-Hi: A Theory of Corporate Responsibility: Linking Profit Making and Societal Interests. Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-503-11478-8 , pp. 87 ff., 112 ff.

- ↑ ibid., P. 118 ff.

- ↑ Ina Bickel: Corporate Social Responsibility: influencing factors, success effects and inclusion in product policy decisions. ISBN 978-3-8366-7829-2 , p. 36 ff.

- ^ Archie B. Carroll: The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility. Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders . Business Horizons, July / August 1991, pp. 39-48.

- ↑ Martin Müller, Stefan Schaltegger: Corporate Social Responsibility - Trend or Fad. Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86581-053-3 , p. 56.

- ↑ Martin Müller, Stefan Schaltegger: Corporate Social Responsibility - Trend or Fad. Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86581-053-3 , p. 58.

- ↑ Matthias Wühle: With CSR to corporate success . Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-0259-0 , p. 32.

- ↑ Matthias Wühle: With CSR to corporate success . Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-8364-0259-0 , p. 29ff.

- ^ Aristoteles: Politik I 13, 1259b, Reinbek 1994, p. 71.

- ↑ Daniel Klink: The Honorable Merchant - The original model of business administration and individual basis for CSR research. In: Joachim Schwalbach (Ed.): Corporate Social Responsibility. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft - Journal of Business Economics. Special Issue 3. Gabler, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8349-1044-8 , pp. 57-79.

- ↑ RM Cyert, JG March: A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs NJ 1963.

- ↑ Oliver Herchen: Corporate Social Responsibility. How companies deal with their ethical responsibility. Norderstedt 2007, ISBN 978-3-8370-0262-1 , p. 19 ff.

- ↑ COM (2011) 681 A New EU Strategy (2011-14) for Corporate Social Responsibility. ( Memento from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The European Commission's strategy on CSR 2011–2014: results, deficits and future challenges, available at: The European Commission's strategy on CSR 2011–2014: achievements, shortcomings and future challenges. ( Memento from March 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Multi-stakeholder Forum on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). ( Memento from April 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL amending Council Directives 78/660 / EEC and 83/349 / EEC with regard to the disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large companies and groups , COM (2013) 207 final / 2013/0110 (COD) . Text also relevant for the EEA.

- ^ Arnold Prentl: Corporate Social Responsibility as a topic of management consulting: taking into account ÖNORM S2502: 2009, ISBN 978-3-639-38498-7 .

- ↑ Andreas Suchanek, Nick Lin-Hi: A concept of corporate responsibility. ( Memento of April 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 756 kB) Discussion paper No. 2006-7 of the Wittenberg Center for Global Ethics.

- ↑ a b Netzwerk Recherche: “There is still light burning in the lobby”, documentation 12. MainzerMedienDisput (PDF; 2.8 MB), pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Martin Müller, Stefan Schaltegger: Corporate Social Responsibility - Trend or Fad. Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86581-053-3 .

- ↑ Apriori Business Solutions: Career models 2010: Influences, developments and success factors. Aschaffenburg 2009.

- ^ Andreas Wieland, Robert B. Handfield: The Socially Responsible Supply Chain: An Imperative for Global Corporations. In: Supply Chain Management Review. Vol. 17, No. 5, 2013, pp. 22-29.

- ↑ Directive 2014/95 / EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 22, 2014 amending Directive 2013/34 / EU with regard to the disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large companies and groups

- ↑ buzer.de: Changes to CSR-RL-UG CSR-Guideline-Implementation Act. Retrieved June 2, 2017 .

- ↑ Greenwashing - The dark side of CSR | Responsibility . In: RESET.to . ( reset.to [accessed June 2, 2017]).

- ↑ Kathrin Hartmann in an interview with SOS Mitmensch ( memento of the original from June 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.