The adventures of the Oijamitza

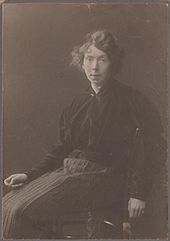

The Adventures of Oijamitza is a novella by the writer Elisabeth Siewert (1867–1930). The story takes place in the writer's West Prussian homeland in the last quarter of the 19th century.

The novella, published in 1928, is about the 16-year-old landowner's daughter Luise - later called Oijamitza - and the girl's attempt to break out of the conventions of upper-class rural life, which are perceived as rigid and restrictive . She hopes to find the longed-for freedom at the side of the robber Baßling, who is drawn to some extent as the idealized "noble robber" of the robber novel . Luise experiences some adventures at Baßling's side and falls in love with the honest bird of prey . Even if the term “adventure” is the title, Siewert is not interested in an exciting description - the adventures remain rather harmless and are sometimes only touched upon. Rather, Siewert is concerned with the description of the characters and their failure. The real adventure is the girl's breakout and her failed love affair. Failure is accomplished in the plot with the shooting of the robber, but ultimately Siewert leaves Luise-Oijamitza to herself (broken to herself) , her poetic view of life and her inability, reality and dream, convention and desire for freedom, life and self-realization To bring harmony fail.

The novella shows a multitude of parallels to other texts by Siewert, whose novels and stories always revolve around her memories of childhood and the landscape in West Prussia and reflect contemporary reality . In addition, like many other Siewert texts, the text has clear autobiographical features.

Publication and division

The novella is one of Siewert's last published works. It appeared in 1928 in the anthology Der Sumbuddawald published by Der Ring , the official organ of the young conservative German gentlemen's club . In addition to The Adventures of Oijamitza , the book contained the Siewert novellas The Sumbuddawald (pp. 119–168) and The sevenfold life of the shepherd Mathias. (Pp. 169-239) . The 111-page novella The Adventures of Oijamitza begins on page 7. From page 31, Elisabeth Siewert has provided the novella with five subheadings:

- The ride (p. 31)

- First adventure (p. 40)

- Second adventure (p. 49)

- Third adventure (p. 62)

- Return (p. 81)

The following summary presentation of the content deviates from Siewert's classification for better, more comprehensive clarification.

content

Scandal on the estate: I want a robber

For the 16th birthday of the beautiful landowner's daughter Luise - later called Oijamitza - the parents hold a big party. Pressed by her younger sisters, who tease her, which nobleman or officer she wants to marry, to the horror of the embarrassed company and above all of the mother, she only says: "A robber".

“Luise explains in a dry, empty voice, while she stared at her cup and a cold fire rushed through her: 'I want a robber, right. I will be happy as a robber woman. I will cook soup the beggar-style and caraway-seed food the scoundrel style. Right now I like a tight budget. So today, different tomorrow ... The robber is not allowed to touch me, but he will love and adore me and listen to what I tell him. '"

Desperate, Luise locks herself in her room and lets off steam, crying, a being angry with the desire for freedom and hunger for eternal bread . (P. 17) Only Wina, the down-to-earth widow of a former gardener, understands her and finds access to her. Bassling, Niklas Karlmann, bad Lothar , that would be one for them. (P. 21) “Nobody else strokes me. I don't know what a hand is and can ", Luise grumbled. "The groom's hand will be the right one," Wina remarked casually. (P. 23) The child plunged into poverty is confronted by the cold, convention-minded mother “created for her territory”, who secretly forged marriage plans for Luise with the heir of a majorate . At Luise's admission, I have cause, however, to behave much worse and yet my mother refuses to do so, horrified, said a young girl from a noble family who lives in abundance. Luise answers: O abundance, I sin for want . The mother throws at her head that she is impertinent and that she does not make sense of her (p. 25f). I see your way, thought the angry mother. Let a man watch him deal with this overstrained thing. (P. 27)

Escape with the robber bassling

In the next scene Wilma packs Luise's bundle and Luise finds herself on a single horse next to the robber Niklas Baßling . The writer leaves open whether Luise is dreaming of the adventure, possibly already into the scene with Wina, locked in her room, or even into her "slip" at the party. There is no farewell to the estate, it is not mentioned whether the parents know about the trip, so that a secret escape can be assumed. In addition to bassling, who could be called a guide for the blind or underage (p. 31), Luise breathes the scent of freedom.

“ How much ransom will your father throw out for his daughter? asked Niklas Baßling.

None at all, because I won't be back.

So, so . Niklas Baßling laughed a little.

I want life the way it is.

How is it, Miss?

Like the ride. Unsure, unknown, treacherous, dangerous, blissful. And something else. But the horse is the magician who gets through. I admire the horse.

Everything the horse and nothing the guy. "

Baßling explains that he will call Luise Oijamitza , which is right for Luise. In conversation, Oijamitza and the robber quickly discover that they are connected with each other. Both reject the churches because they don't enjoy being locked up and don't like fossils . (P. 36) Bassling, of whom it is said elsewhere that he only made it to the upper tertia (p. 79), is characterized as follows:

“Bassling had to think of the horrors of his high school days. Of his colossal dreams and the constant snipping and sticking and sticking with thumbscrews that had been done on him. [...] This freak of an uncle who had denied him, the orphaned boy, what little was nourishing for him. This philistine from an aunt who had tried to sober him up early in the morning and destroy him with her coffee and her garbage. O, oh, world-shaking lust of the noise, when the fearful, crutched, rubbish, marrow-free and salt-free world of the small town went to pieces, from his point of view, and he, like a fresh and flawlessly feathered bird of prey, had come up to start his apprenticeship on his own account. An honest bird of prey cannot fall into the role of a domestic cock, breeder pel, or Christmas turkey and lie. "

The adventures with the robber bassling

First adventure, ghost

In the robber's hut deep in the forest, bassling entrusts Oijamitza with the tasks of fetching water from the river and plucking pigeons . A memory seized her; a deep and hot erupting joy of life sprang from her, overflowing her feelings. Baßling watched her sunken, indulgent smile and how she began to manipulate as if it were the most delicious, most important thing in the world. (P. 45) Baßling orders her to disguise herself as a ghost and to frighten and drive away the pitch burners, along with women and children who had come dangerously close to the robber's hut while doing their work. After she passed her first adventure with flying colors, she lies contentedly in bed in the evening and says: With this dull, bluish-white evening sky, which vaults high over the misery and miracles, I am overflowing with a real, great, staggering, sweet joy of death breastfed. (P. 48f.)

Second and third adventure, horse robbery

Oijamitza and Baßling take up the theme of religion again and, in great agreement, draw a real temple , a sanctuary with gods and demons (pp. 50–53). At a foundation festival of the fire brigade, at which the robber is not recognized, Baßling ponders the bass . The tones of the instrument correspond to his attitude towards life. Bassling fell in love with this bass; [...]. "That was once a way of life, something that expressed will, this bass," he said to himself. (P. 55f) In the robber's hut, one of Baßling's two lads stammered that he had fallen in love with Oijamitza. Thereupon Bassling chases the youth away forever, but allows him to kiss Oijamitza's hand in parting. Oijamitza had got up, driven by a movement that was completely new to her, for she had never in her life had the feeling or even the pleasure that a young man had felt affection for her. Far more likely she believed that she was shy, even fearful. The youth snapped roughly at her hand and began to kiss her like a slanderer. Oijamitza disliked this greatly. (P. 60f)

The actual "adventure", a horse stealing, is mentioned in the opening paragraph, but then only taken up again without further description in the section Third Adventure with the mention that the robbery was a splendid success (p. 62); Oijamitza was not involved, she stayed in the hut. Since gendarmes are on their trail, the robber couple rides deeper into the forest to a new hiding place. Oijamitza is allowed to ride the stolen white horse that expresses her longing for white purity and is blessed. Baßling describes Oijamitza as an overstretched doll and grumbles that everything is poetry for her (pp. 63–68). Wilma appears in the hut and wants to bring Oijamitza back. The estate would not be for the best (p. 69f). After a few days of hesitation, in which she is torn to find her soul (p. 79), Oijamitza decides to return.

Interlude: temporary return to the estate

Without further subtitles, Elisabeth Siewert subsumes the remainder of the novella from page 81 under the heading Return . This is possibly deliberately ambiguous, because Oijamitza returns several times. First to the estate, then back to the robber Baßling and at the end she follows Baßling either to death or returns to the estate again.

The mother had killed a heartbeat . The small children have a fever, their bodies are covered with rashes, and their father is sick too. The “regiment” in the house has taken over the capable, noble Elgone (p. 83), who quickly replaces the mother, is soon admired and adored by the father for her energy and, like Oijamitza, now Luise again, speculates and you directly too says, will probably get married soon (p. 95f). For the time being, Elgone does not let Luise see the small children or the father and assigns her tasks with which she can make herself useful until everyone has recovered. In the domestic chores it works for the time being. When Elgone finally lets her go to the almost recovered, the father finds it difficult to forgive her and he only offers her hand at Elgone's pressure. When everything was fine again on the estate and the servants returned, Luise noticed again that she was out of place in the tightness of the conventions of the estate, which in her view was merely "outer", adapted functioning in the kingdom of the Elgone ( Pp. 83-96).

“And Elgone grasped the unknown, eerily and strongly vibrating with forces with Luisen's hand. I feel it to you, you don't really root yourself in your circle , she said uncertainly. Roots ? Asked Luise with a frown. In my circle? You mean in yours, because I don't have one. I mourn to heaven like our poorest wildest landscape and would like to understand how to sing the praise and the song that I owe to the Creator in the bliss of being there. "

Return to Bassling and the Robber's Death

Again, she lets the (supposed) semblance of life behind, storms out of the house and submits to the already waiting robber's arms, it was up to him like a blazing fire on succulent mighty tree trunk and shouted, losing itself in the difficult landscape of his face [: ] “Apparent death over, tetanus, fool fight over. I now always go with you. " (P. 96f) In a passionate love she says:

“We both want to get Heaven to give us voice and words, even sayings, with and without rhyme. [...] With humility and pride we must express what is necessary. [...]; great feeling and consciousness of pride because of participation in that glory, world size, infinity, power. The best of life is its unreality, so wind the wreaths out of star eternity. "

Oijamitza is also responsible for fetching water in the new robber's hut. Intoxicated by the landscape, the aromatic air and her happiness, the water collector says hopefully: That's how it is when you are alive. [...] That's how it is when you have time to be yourself. [...] It is sublime to be the girl who is seized by man's love, who takes hold of the man, who finds the world and herself. (Pp. 105, 107) After awakening, the happy mood gives way more and more to the anxious waiting for Bassling who had left the hut. Of jealousy fantasies plagued she imagines could drive with which women are Baßling grade. Chased by the gendarmes, the exhausted bassling comes into the hut. The couple only have minutes that are filled with intimate expressions of love. A gendarme shoots the robber (pp. 108–115).

A gypsy, whose hints had previously suggested that she was Bassling's lover, assured the girl that Bassling wanted Oijamitza's love even now, in heaven. "Then I want to sleep to meet him," says Oijamitza, looking gloomily around. In the final image of the story, she puts her head in the gypsy's mother's lap and it remains to be seen whether she will follow Bassling to death (p. 118).

Place and time of the action

Like almost all of Siewert's stories, this story also takes place in her West Prussian homeland. There are few indications of the specific location of the event. Several times only Wirthy (as Klein-Wirthy ) is mentioned, which is located northwest of the Budda estate , where the writer was born and grew up. The Königliche Forst Wirthy on Bordzichower See formed the northeastern branch of the Tucheler Heide . The Arboretum Wirty , founded in 1875, emerged from the forests and possibly already existed when Oijamitza and Baßling roamed the forests. Siewert lets the couple watch a pageant of the forest society and describes the tasteful facilities of Klein-Wirthy (p. 76ff). Due to the strong autobiographical references and the complete works of Siewert, it is obvious that the plot is to be set in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Embedding in the complete works of Siewert

The novella contains many parallels to other texts by Siewert and contains autobiographical traits. Elisabeth Siewert, like her character Luise-Oijamitza, grew up as a landowner's daughter with several sisters.

Period of origin

Although the novella is one of Siewert's last published works (1928), at least the idea for the story is likely to be much earlier. The Siewert sisters thought up stories as early as they were children. The art historian Roman Zieglgänsberger points to an ink and pen drawing by his sister, the painter Clara Siewert , from around 1905 , with the very similar title The Adventure of Oljamizza and therefore suspects that the basis of the text - as in the novel Die Geckin by 1928 - developed together by the sisters in their youth. Also the scene in which Luise locks herself in her room ( lay again, her little head in the confused mass of her ash-blonde hair as if on an extra pillow on the white pillow. […] She was now […] an honestly stupid cradle-child , without any responsibility, without abnormal conditions and terrible experiences. p. 20) corresponds to a picture of Claras: The picture Mother at the bed of her sick child (1902) shows a worried mother who looks down at her child helplessly and with a sad, understanding look lying curled up on the sofa, feeble and afraid.

Language and style: no tension despite adventure

In 1914, wrote Austrian literary historian , writer and feminist Christine Touaillon in a review , voltage lies Siewerts art infinitely remote . Instead of a dramatic escalation, the events slipped into one another as in reality. Although the term " adventure " in the plural form gives the title in this novella, the adventures are comparatively unspectacular (playing ghosts) or are only told in fragments like the horse robbery, of which at the beginning of the third adventure it is only - almost laconic - is called him was brilliantly successful. In this novel, too, Siewert is not concerned with building up a tension arc and adventurous stories like in the classic adventure novel . The adventures are only a means of showing what feelings the transgression of conventional boundaries arouses in the protagonists, especially in Luise / Oijamitza.

Work parallels and autobiographical references

Breaking from the conventions

In a 1911 review, the women's rights activist Gertrud Bäumer stated that the sketches collected by Siewert in Kinder und Menschen (1906) were a ceaseless struggle to break out of the barren and cramped country life, out of the ordinary, out of poverty and cold. Luise-Oijamitza also tries to break out of the conventions, which are felt to be constricting and frozen, and sees the robber Baßling as the embodiment of the longed for freedom. Baßling plays the role of the idealized “noble robber” of the robber novel , who took up the bourgeois protest attitude and the pathos of freedom in the German Sturm und Drang . The Siewert sisters did not go the traditional way either, but moved to Berlin to realize themselves artistically and remained in search of themselves all their lives.

Similar to Baßling, in the novella Van Braakel (1909), the cabin boy from a reading book for the little girls from an estate stood as a metaphor for everything that was free, idiosyncratic, bold, despising of death and exhausting life ; who, even by force, wanted to break through the orderly, boring security, the civil equilibrium and is looking for connections . Life, perceived as restrictive, condenses in the drawing of the mother and later of the noble Elgone. Siewert characterizes the decent, contented mother, created for her area, as rather cold and frozen, who is uncomprehending about the longings of her daughter and who really only has in mind to marry her off advantageously. She considers her daughter to be impertinent and exaggerated (p. 25f), a term that Baßling later takes up with the phrase exaggerated doll (p. 67). The father remains largely in the background and is rather proud of his daughter, who is once again the focus and outshines everyone. He comments slightly ironically on his wife's marriage plans with a hot, bearded face : She should go up, higher, and even higher, he laughed furtively (p. 14).

Religions

Another aspect that runs through many of Siewert's works is her often clear criticism of the religions , which, in accordance with upper-class life as a whole, she also characterizes as frozen:

“'Are you happy about the Protestant church or the Catholic one?' asked Bassling. ,What makes you think that? I don't enjoy being locked up. ' ,Neither do I.' Baßling laughed extremely well […]. 'Then maybe the synagogue makes you happy?' 'I haven't seen any and don't like to see any. I don't like fossils. ' [...] "(p. 36)" It was always like this: when religion was mentioned, her senses melted away, her eye turned inward, her ear became deaf. "

Already in the novella of 1909, the title character “Van Braakel” was given no answers by the Bible and the “black square devotional books” and instead of “divine being” the boy demanded “the simplest thing [...] from the adults, the observations of a single, simple day set forth with sincerity ”a. Christine Touaillon wrote in her 1913 review of Siewert's 1913 novel Lipskis Sohn from 1913 on the figure of the imaginative widow Felsken: "Her father's Catholicism and mother's Protestantism put her in a skeptical position about everything that means religion."

Search for the lost childhood

A central theme in Siewert's texts is the longing for a lost childhood. She herself never felt at home in Berlin and longed for her childhood days on the estate. According to Zieglgänsberger's portrayal, Siewert sees childhood as the only happy and carefree time in a person's life and repeatedly explores the question in her texts […] of how it was possible that this childhood heaven was lost. In Das Himmlisches Kind 1916 Siewert emphasized in the form of a self-talk how much she draws her strength and wealth from happy memories. She glorified her childhood with the words I cling to the little child, I adore it, I pull it out of the twilight and look at it with stunned delight. And Oijamitza, too, travels back to her happy childhood while performing the simple tasks that her bassling had assigned: a memory seized her; a deep and hot erupting joy of life sprang from her, overflowing her feelings. (P. 45) As she fell asleep blissfully according to Baßling's testimonies of love, she reached the perfection of her divine childhood, where she had and enjoyed everything, where she lived in the love hut and called the magic brother. (P. 107)

Impracticability of the poetic view of life, reality and dream

With a slight growl, but with a friendly mood, bassling presents Luise in one scene:

“And you, for thunderstorm, only mean poetry, always and always from morning to evening, it seems to me. Everything that is not for you makes you sick, you young girl from a noble home. - From one point of view you see everything and if it is not correct, you pass over. "

As early as 16 years before this novella was published, Lou Andreas-Salomé had determined that the same problem was encountered in Siewert's works in ever new interpretations: the beauty and impracticability of the poetic view of life. The oppressive toil of those who do moral work in the sweat of their brow runs through almost all the stories, while they prefer to think back to the paradise from which they have been driven since childhood. Christine Touaillon had also stated in 1914 that Siewert was always concerned with the question of how people can come to terms with life, how can they come to terms with it. The heroes of their stories did not feel comfortable in their existence. They lived in a narrow, sometimes self-made, pressure was on them. They feel an unclear longing for a distant life. Often they cannot say what they want themselves, but they have to get out of this captivity or they perish because of it.

In this novella, too, Siewert lets the main character fail because of her inability to reconcile reality and dream, convention and thirst for freedom, life and self-realization. Just me, […] broken on myself, languishing and sick in my surroundings, lets her say Oijamitza once (p. 67). Siewert also adds something egoistic to the girl's dream life (everything that is not for you makes you sick) , inconsiderate and irresponsible. The writer and art critic Paul Fechter spoke of Siewert's inner two- tier structure and of her struggle for the balance between the worlds : In the strangely real fairytale-like character of the “Adventures of Oijamitza” of 1928, she opposes reality with her no, but cannot prevent it in the end, in the shape of the gendarmes, she breaks hard into the dream world of the girl who goes to her robber chief in search of life. Beyond this Fechter's note, only a short review is known of the novella in the Baltic monthly sheets , which merely states: We know the shy tenderness with which [Siewert] the unfamiliar and yet so down-to-earth German of her Kashubian homeland for the common people of the Landes puts it in his mouth without any trace of parody, and we also understand why the landlord's daughter who chased after a robber captain, as the inner German Raabe might be able to see, is no longer called Luise, but Oijamitza.

The love adventure

Behind the girl's longing and her search for life is ultimately the search for love, so that the eponymous adventure can be classified under a great adventure, the love adventure. “Nobody else strokes me. I don't know what a hand is and can ", Luise grumbled. "The groom's hand will be the right one," Wina remarked casually. (P. 23) In the scene with Bassling's boys, she was driven by a movement that was completely new to her, because in her life she had never had the feeling or even the pleasure that a young man had felt affection for her. (P. 60f) At first there were no even the smallest touches: Baßling wanted to run his index finger over her nose. But this nose was built so delicate, noble and innocent, [...] that he refrained from it out of respect. (P. 52), after returning to Baßling after the interlude on the estate, she lost herself blissfully in the heavy landscape of his face and Baßling held Oijamitza close to himself. (P. 97). It is sublime to be the girl who is seized by man's love, who takes hold of the man, the world and herself. (P. 107)

But Luise-Oijamitza, whose conflict is already expressed in the double naming, cannot live in the conventions, in reality, but only in her dream world. In the forest scene while watching the parade in Klein-Wirty, Siewert lets the girl feel her inadequacy, her failure in herself. Full of longing, Oijamitza looks at the slender, delicate-faced bride who - unlike her - has managed to find fulfillment and love in the so-called orderly relationships at the hand of the extremely pleasant, intelligent and fresh-looking forest officer, next to whom she is so soulful walked . (P. 77f) Baßling senses Oijamitza's turmoil and is amused: Has the fire burned down? [...] Are you attracted by the salon, the fine gesture, the smooth conversation? […] Strange, even on the bush island over there is a white bench, intended for civilized lovers who do not prefer to lie on the womb of the earth to find their destiny. (P. 76, 78) With Baßling's death, love also failed. Siewert also makes it clear that in the end the orderly conditions prevail despite all their supposed constriction and paralysis, by attributing the leadership of the group of persecutors who led the robbers to the handsome young forest official (that forest official and groom from the parade in Klein-Wirthy) and finally shot in front of the girl's eyes (p. 114ff).

Neither Elisabeth Siewert nor her two sisters, with whom she later lived together in Berlin , was granted the transition from a secure childhood, experienced as loving, to an adult, sustainable love affair . All remained unmarried and nothing is known about closer relationships. Like her character, the writer herself failed because of reality. In constant longing for her lost childhood and bitter about her lack of literary breakthrough, she died in mental confusion. The older sister Clara, who survived Elisabeth by fifteen years, also failed with her painting, which the Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg relocated to the rediscovery of her work in 2008 at an exhibition Between Dream and Reality , and died in complete impoverishment.

literature

Mentioned works by Siewert (chronological)

- Children and people . Novellas. Karl Reissner, Dresden 1906, 271 pp.

- Van Braakel . In: Socialist monthly books - International revue of socialism. Ed .: Joseph Bloch . Issue 15 1909. Verlag der Sozialistische Monatshefte, Berlin., Pp. 236–241 ( full text in the online edition of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung library ).

- Lipski's son . Novel. S. Fischer Verlag, Berlin 1913, 247 pp.

- The heavenly child . In: Sozialistische Monatshefte , Issue 22 1916, pp. 43–46 ( full text in the online edition of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung library).

- The Geckin (novella). In: The art warden . Verlag Kunstwart, Dresden and Callwey, Munich, September 1928.

- The Sumbuddawald . Novellas. Ring-Verlag, Berlin 1928. 239 p. (Contains the stories: The adventures of the Oijamitza (p. 7–118), The Sumbuddawald (p. 119–168) and The sevenfold life of the shepherd Mathias. (P. 169–239 ))

Secondary literature (alphabetically by author)

- Lou Andreas-Salomé : Elisabeth Siewert . In: The literary echo . Edited by Ernst Heilborn . 14th year 1911/12, September 15, 1912, Berlin, pp. 1690–1695.

- Gertrud Bäumer : The woman and the spiritual life . CF Amelangs Verlag, Leipzig 1911 (on Elisabeth Siewert see pp. 138–141).

- Paul Fechter : History of German Literature. C. Bertelsmann Verlag , Gütersloh 1952. (Originally: Knaur , Berlin 1941.) Quoted here from the Bertelsmann edition in 1957, on Siewert s. Pp. 723-725.

- Clara Siewert. Between dream and reality. With contributions by Renate Berger, Michael Kotterer and Roman Zieglgänsberger. Ed .: Kunstforum Ostdeutsche Galerie Regensburg, Regensburg 2008; ISBN 978-3-89188-116-3

- Christine Touaillon : Elisabeth Siewert . In: Neues Frauenleben, 16th year, No. 1/2, Vienna 1914, pp. 41–46. ( Full text at ALO = Austrian Literature Online .)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Information from chief forester Marter, reproduced by: L (udwig) Beißner , Bonn-Poppelsdorf: Annual meeting in Danzig and excursions from August 4th to 10th, 1911. In it: Königlicher Forst Wirthy . In: Communications of the German Dendrological Society , 1911, editing: Graf von Schwerin , President of the Society; Submission: L (udwig) Beissner, Royal Garden Inspector, Managing Director of the company. P. 343ff p. 344 online

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger, in: Clara Siewert. Between dream and reality. , Pp. 73, 75, 91, 155 (Fig. 3), 167 (Fig. 73).

- ^ Christine Touaillon: Elisabeth Siewert , 1914, p. 42.

- ↑ Gertrud Bäumer: The woman and the spiritual life , 1911, p. 138ff

- ^ Elisabeth Siewert: Van Braakel . In: Sozialistische Monatshefte , Issue 15 1909, pp. 236–241 ( online text ).

- ^ Elisabeth Siewert: Van Braakel . In: Sozialistische Monatshefte, Issue 15, 1909, pp. 236–241 ( online text ).

- ↑ Christine Touaillon: Elisabeth Siewert, 1914, p. 44.

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger, in: Clara Siewert. Between dream and reality. , P. 117.

- ↑ Elisabeth Siewert: Das Himmlisches Kind , In: Sozialistische Monatshefte , 1916, S. 44 ( online text ).

- ^ Lou Andreas-Salomé: Elisabeth Siewert , 1912, p. 1691 f.

- ^ Christine Touaillon: Elisabeth Siewert , 1914, p. 41f.

- ^ Paul Fechter: History of German Literature. P. 724.

- ↑ HWB: Elisabeth Siewert, Der Sumbuddawald. In: Baltic Monthly . Edited by Woldemar Wulffius, Werner Hasselblatt , Max Hildebert Boehm . 59th year (1928), Verlag der Buchhandlung G. Loeffler, Riga 1928, p. 248.

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger, in: Clara Siewert. Between dream and reality. P. 31f, 185.