Dolaucothi gold mines

Coordinates: 52 ° 2 '28.7 " N , 3 ° 57' 8.1" W.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines , also known as the Ogofau Gold Mines , are Roman mining facilities above and below ground located in the Cothi Valley , near Pumpsaint in Carmarthenshire , Wales .

They are the only mines for Welsh gold outside of the so-called Dolgellau gold belt and have the official status of a designated archaeological monument ( Scheduled Ancient Monument ). They are also the only known Roman gold mines in Great Britain , although the possibility cannot be ruled out that the Romans also exploited other sources such as Devon , North Wales and Scotland . The facility is significant as it provides a glimpse into the sophisticated technology of Roman mining methods.

History of gold mining

Archaeological research suggests that gold mining probably began at this point in the Bronze Age , possibly by washing the gold-bearing gravels of the Cothi River, the most basic method of gold prospecting .

Roman gold mining

Sextus Iulius Frontinus was sent to Roman England in 74 AD to replace Quintus Petilius Cerialis as governor . He subjugated the Silurians , Demeter and other hostile tribes in Roman Wales and built a new military base in Caerleon for the Legio II Augusta as well as a network of small Roman forts 15 to 20 kilometers apart and used to support Roman auxiliary forces. During his tenure, he probably had the Pumsaint Fort built in West Wales, primarily to exploit the Dolaucothi gold deposits. After his tenure, he later directed the restoration of the aqueducts of Rome . The Romans probably used slaves for much of the work, although the Roman army was probably also directly involved in the mining activities, mainly due to the engineering knowledge in the planning and construction of aqueducts, reservoirs and water basins or cisterns .

The duration of the occupation of the fort ( Luentinum according to details in Claudius Ptolemaeus ) and the associated vicus show that the Romans operated the mine during the entire 1st and 2nd centuries (from about 78 AD to about 125 AD). Various pottery items - including terra sigillata recovered from the Melin-y-Milwyr reservoir within the mine complex - show that the mine was in operation until at least the late 3rd century. After the end of the military occupation, the mine may have been operated by Roman-British civilian contractors, although the mine’s later history has yet to be clarified.

Later history of the mines

After the Romans withdrew from England in the 5th century, the mine was abandoned for centuries. The fact that gold was found in this area only became generally known in the 18th century with the discovery of a Roman gold treasure, which among other things contained the Dolaucothi gold wheel shown above. Other items in this gold treasure were snake bracelets, which, due to the softness of the gold, could be easily wound around the arm. These items are in the British Museum and are on display in the Roman-British Department. A piece of gold ore, which was found in 1844 by Henry Thomas de la Bèche in the area of the gold mine, proved the existence of gold deposits there.

Mining resumed and attempts were made to turn gold mining into a profitable business in the early 20th century, but they were abandoned before the First World War . In the 1930s a 130 meter deep shaft was sunk to find new gold veins. Due to neglect and the flooding of the deeper areas, the mine was finally closed in 1938.

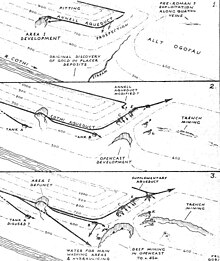

During this last period the ancient underground structures and the remains of the old drainage systems were discovered. The extensive remains of the system on the earth's surface, especially those of the extraction by means of water power, were only discovered in the 1970s through thorough field work and survey. While no other such facility has been found in England, it is likely that other mines can be found by following the remains of the aqueducts and reservoirs. They are often discovered because they cast clear shadows when the light hits them at an angle. For example, water basin A was first observed when morning light fell diagonally on the Allt Cwmhenog hill on which the structure lies.

Roman mining methods

The Romans made extensive use of water, brought in by means of aqueducts and moats (the longest of which was about seven miles from its source in a ravine of the river to the mine) to exploit the gold veins that were underground on the slopes above today's Pumpsaint village. Small watercourses on the slopes of Mynydd Mallaen, Annell and Gwenlais were initially used to provide water for mining. Several basins to hold the water are still visible above an isolated open pit dug into the side of the hill north of the main quarry. The large aqueduct descending from the Cothi River crosses the opencast mine and thus proves that it was built afterwards.

Mining with hydropower

The water was collected in the water basins and then drained off at once to wash away the top layer of soil, exposing the bedrock underneath and the gold veins that may have been contained in it. Pliny the Elder describes this method of hydraulic prospecting in a dramatic way in his Naturalis historia , probably after his experiences in Spain. The method was later called hushing , flushing or booming in England and survived as a mining method into the 17th century. A not dissimilar method is used today to break down soaps such as alluvial tin ( hydraulic breakdown ). A smaller version of this mining method is panning for gold , and both versions of the methods could have been used to mine alluvial gold near the cothi itself. This is indicated by a large aqueduct, which taps the river almost two kilometers upstream and reaches the facility at a lower level than the other aqueducts.

The water brought in by the aqueducts has also been used to wash crushed gold ore and possibly also to power tamper mills to crush the gold ore (Lewis and Jones, 1969).

The Dolaucothi Aqueducts

One of the first aqueducts was built high on the eastern slope of Allt Cwmhenog and was connected to a small stream about three kilometers away. At the point where it swings from the front of the hill to the west side of the hill, there is a large pool of water at its end. A large gold vein must have been discovered here, as there is a large opencast mine below the basin. Later the large aqueduct, which taps the Cothi about 11 kilometers northeast, was led across the open pit with a gradient of 1 to 800 and must therefore - as already mentioned above - be younger than the open pit. The construction of the mining sites and water basins is connected to the aqueduct system and thus goes back to the Romans. Radiocarbon dates classify the aqueducts as the oldest remnants of mining activities.

In contrast to this open-cast mine, the prospect for gold using several water basins that were found in the area of the plant found no gold vein and the basins were abandoned. The water basin A (see photo above and the development scheme of the mines in Roman times for the location) near the northern open-cast mine was probably intended to explore the end of the gold deposits that were exploited in the large open-cast mine. It obviously did not encounter the gold deposit and was abandoned. The water supply was probably ensured by a small moat that branched off from a small stream upstream in the valley of the Cothi before the large aqueduct was built.

The open pit

The exploration in the area of the open pit was successful, and various open excavation sites are visible along the aqueduct below the large water basins. The only exception is the last and very large water basin, under which there are two reservoirs. This complex was probably used to wash out finely ground ore to extract gold dust. Other moats and water basins are on the line of the great aqueduct, some of which are shown on the map above.

They encircle the edge of the very large open pit mine, and water basin C in the photo is one that was built on top of the main aqueduct. A vein of gold was found here, assuming mining below it. The basin was later modified to feed a vanity, which was placed on its left side (near the person in the photo) and was probably used to wash out the ore extracted here. The Romans created similar pools of water when they followed the great gold vein further down the slope to the road and to the main mining area. The Carreg Pumsaint (see below) was later built directly on the street itself in the open space next to a large mound of earth, which is interpreted as a deposit of dead rock .

The ponds on the back road from Pumsaint to Caeo were probably part of a cascade for washing. The upper water basin has supplied a large amount of Roman pottery dated from 78 to at least 300 AD (Lewis 1977; Burnham 2004). This upper pond is known as Melin-y-Milwyr (Soldiers Mill), an intriguing name that could suggest the use of watermills in Roman times.

A large mill complex is known with the Mills of Barbegal in the south of France , in which no fewer than 16 mills (in two rows of eight mills each) were built into the side of a hill and supplied with water from a single aqueduct. In the two rows of overshot waterwheels , the higher water wheel fed its water to the one below. The mill supplied the region with flour. Similar systems with a series of overshot water wheels were also used by the Romans to drain mines . The sequence of the water wheels allowed mine water to be transported over great heights. A large drainage system from 16 water wheels was discovered in the 1920s in old Roman mines on the Río Tinto in the 1920s. The water wheels were arranged in pairs and could lift the water over almost 25 meters. In Dolaucothi, the remains of a water wheel that could be part of such a facility were discovered when mining activities resumed in the 1930s.

Melin-y-Milwyr

The water basin at the head of the narrow road from Pumsaint to Caeo was thought to be modern because it still contains water. However, when the water level was particularly low in 1970, a large amount of Roman pottery was found in it. This find proves the Roman origin of the basin and its construction during the Roman mining activities in the mine.

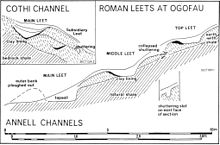

The above cross-section shows that it was connected to a smaller water basin directly below today's road via an underground, dry-walled water pipe. The lower basin still has water today, but it is already very silted up. Among the fragments, in addition to Terra Sigillata, there was also utility ceramics from a total of over 100 different pots that fell into the basin when the mine was in full operation. An analysis of the fragments shows a distribution of the fragments from the late 1st to the end of the 4th century. Since the large and small fort under today's village of Pumsaint were abandoned in the middle of the 2nd century, operations must have continued for a long time after the withdrawal of the Roman military. This suggests that there must be a large mining settlement in the vicinity of the village of Pumsaint that has yet to be found.

The actual function of the cascade is related to the methods of extracting the last remnants of gold from the broken ore. There were probably washstands between the two water basins so that a gentle stream of water could be used to wash the ore on the rough surfaces so that the fine gold particles could collect in the depressions and be picked up there after the process was complete. The cascade may have been built towards the end of the first century when mining switched from open pit mining to underground.

Carreg Pumsaint

The Dolaucothi mining facility provides one of the earliest records of the Romans using water-powered hammer mills to crush ore (Burnham 1997). The ore was likely quarried on the famous Carreg Pumsaint, a stone erected many years ago after the Romans left. There are parallels with similar stones in other ancient Roman mines in Europe, and the indentations in the stone were caused by a hammer mill, probably powered by a water wheel. Such a hammer was moved at regular intervals as soon as the indentations on the stone serving as an anvil became too deep. This created a series of overlapping indentations on the surfaces of the stone. The hammer must have been of considerable size, considering the dimensions of the indentations shown in the picture above. The stone is the only one of its kind found in the area of the complex, but is not unique as such, as Burnham refers to other stones of similar shape from Spain. If one side of the stone was too worn, it was simply turned so that the other side was facing up so that the stone could be reused several times. When the stone was found many years after the Romans left in the Dark Ages , it gave rise to the legend of the five saints who left the imprint of their heads in the stone when they were surprised asleep by the devil.

Underground mining

The miners followed the underground ore veins with shafts and tunnels, some of which are still preserved in the area of the plant. Remnants of Roman water art were found in the 1930s when the mine was briefly reopened. The most interesting discovery was that of an overshot return wheel , which now in the National Museum of Wales is. It was found with charred logs, suggesting that the technique of setting fire was used to break open the hard quartz that contained the gold. A similar but larger wheel was rediscovered during mining operations near the Río Tinto in Spain and is now on display in the British Museum in the Roman section in a prominent place. The Spanish installation consisted of no fewer than 16 water wheels, each of which passed its water on to the next in succession. Each waterwheel was operated like a treadmill , from the side rather than from above. This was a hard and lonely job for the miners who operated the wheels to lift water from the bottom of the mine.

Since the remains of the water wheel in Dolaucothi was found almost 25 meters below all known tunnels or excavation caves, it must have been part of a device similar to the one in Spain. The gold mining of Dolaucothi was technologically advanced and sophisticated, which suggests that the Roman army themselves promoted the exploitation of the mine. The construction of such drainage machines and their widespread use for irrigation and lifting water in thermal baths was described by Vitruvius as early as 25 AD.

Elsewhere in the mine, at Pen-lan-wen, water must have been scarce. A culvert could have brought water from the main aqueduct or one of its water basins, but this has not yet been proven. The ore vein stretches along the hill for a long distance and was exploited by means of a trench. This method was used by digging the gold vein to depth while keeping the trench open to the top. In this case, ventilating the trench will have become increasingly problematic, especially if the method of setting fire was used. For this reason, three long ventilation tunnels were driven north from the hillside. They are much wider than normal tunnels, so their use as a means of extracting air from the trench and providing safe ventilation during the setting of the fire seems likely. The upper two ventilation tunnels still have a connection to the ditch, the third is currently blocked.

Further processing of the gold

There is evidence that at least some of the gold was still processed on site, as suggested, among other things, by the fully completed Dolaucothi gold wheel brooch pictured above. The manufacture of workpieces such as the partially completed gemstone found nearby requires considerable expertise that only trained workers have, not slaves . No relevant workshops or furnaces have been found so far, but it is likely that they existed at the facility.

Gold bars are easier to transport than gold dust or nuggets, even if a high-temperature melting furnace is required for their production in order to melt the gold at a melting point of 1064 ° C. Pliny mentions such special ovens in his Naturalis historia . A workshop was essential for the manufacture and maintenance of mining tools such as water wheels, chutes for wash basins, sealing lids for aqueducts, equipment for crushing rock and finally pit wood . Official mints may have produced gold coins.

Other Roman mines

The lead mines of Nantymwyn near the village of Rhandirymwyn, some 12 kilometers north of Dolaucothi, may also have been first exploited by the Romans. An indication of this is given by the aqueducts and water basins for hydraulic prospection, which were identified there in the 1970s through both field work and aerial photographs. They are located on the top of the Pen-cerrig-mwyn mountain and the gold-bearing veins have been accessed by several tunnels that descended to the mining sites. There, the ore veins have been mined and the spoil has been carefully filled into the cleared mining cavity. These mining sites are well above the now-closed modern mine - once the largest lead mine in Wales - and the associated processing plant .

Although no other facility is currently known in England comparable to Dolaucothi in terms of extensive hydraulic systems, many other Roman mines are known, some of which have remains of hydraulic workings, including the extensive remains of the lead mines at Charterhouse in the Mendip Hills , Halkyn in Flintshire and many facilities in the Pennines .

Dolaucothi is perhaps best comparable to the gold mines in the Carpathian Mountains near Roșia Montană in present-day Romania , and to the Roman gold mines in northwestern Spain such as the mines of Las Médulas and Montefurado , where alluvial gold was mined on a much larger scale.

National Trust

The National Trust of the United Kingdoms is since 1941 the owner and operator of the plant. The Universities of Manchester and Cardiff were involved in the exploration of the extensive remains in the 1960s and '70s. The University of Wales with its branch in Lampeter is currently working on the archaeological investigation of the facility. The National Trust organizes guided tours for visitors, showing them the mine and the Roman excavations.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Herbert Bucksch: Dictionary Dictionary Geotechnical Engineering Geotechnical Engineering. Vol. 2, Birkhäuser, 1998, ISBN 3-540-58163-4 , p. 255.

literature

- O. Davies: Roman Mines in Europe. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1935.

- GDB Jones, IJ Blakey, ECF MacPherson: Dolaucothi: the Roman aqueduct. In: Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. Vol. 19, 1960, pp. 71-84 and panels III-V.

- PR Lewis, GDB Jones: The Dolaucothi gold mines, I: the surface evidence. In: The Antiquaries Journal. Vol. 49, 1969, No. 2, pp. 244-72.

- PR Lewis, GDB Jones: Roman gold mining in north-west Spain. In: Journal of Roman Studies . Vol. 60, 1970, pp. 169-85.

- RFJ Jones, DG Bird: Roman gold-mining in north-west Spain, II: Workings on the Rio Duerna. In: Journal of Roman Studies. Vol. 62, 1972, pp. 59-74.

- PR Lewis: The Ogofau Roman gold mines at Dolaucothi. In: The National Trust Year Book 1976-77. 1977.

- A. Annels, BC Burnham: The Dolaucothi Gold Mines. 3rd edition. University of Wales, Cardiff 1995.

- Barry C. Burnham: Roman Mining at Dolaucothi: the Implications of the 1991-3 Excavations near the Carreg Pumsaint. In: Britannia. Vol. 28, 1997, pp. 325-336.

- AT Hodge: Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply. 2nd Edition. Duckworth, London 2001, ISBN 0-7156-2194-7 .

- BC Burnham, H. Burnham: Dolaucothi-Pumsaint: Survey and Excavation at a Roman Gold-mining complex (1987-1999). Oxbow Books, 2004.

See also

Web links

- Dolaucothi Gold Mines, The National Trust

- Description of the facility, Dyfed Archaeological Trust website

- Image of Carreg Pumsaint

- Spanish website on Roman technology, specifically aqueducts and mines

- The Roman gold mine of Bessa, Italy

- Las Médulas (Spain), the largest Roman gold mine