Dreyse needle gun

| Dreyse needle gun | |

|---|---|

|

|

| general information | |

| Country of operation: | Prussia |

| Developer / Manufacturer: | Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse |

| Production time: | since 1840 |

| Weapon Category: | Breech-loading rifle |

| Technical specifications | |

| Caliber : | 15.43 mm |

| Ammunition supply : | Single loader |

| Fire types: | Single shot |

| Closure : | Cylinder lock |

| Lists on the subject | |

: paper cartridge 15.43 mm Dreyse

m .: paper cartridge 11 mm Chassepot right

: metal cartridge .56-56 Spencer

The needle gun is a rifle developed by Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse from 1827 in Sömmerda with then new types of needle cartridges that contained the ignition element in addition to the projectile and propellant charge . The rifle was produced the first mass and for military use suitable breech-loading rifle . After a long development period, mass production began in 1840. The rifle was used in various variants mainly in the Prussian army from 1848 to 1876 . The Prussian successes in the German War of 1866 led to a change in infantry armament in other countries as well. The principle of ignition needle ignition was mainly adopted by France as a Chassepot rifle . In addition, the principle of rear loading of the needle gun, the cylinder lock, shaped weapon technology for decades.

history

development

In 1810, the gunsmith Samuel Johann Pauli developed a breech-loading rifle based on a tender from Napoleon Bonaparte , in which a new type of cartridge was ignited with the help of a firing pin . The cartridge contained the projectile, propellant charge and, in a metal base, the detonator made of the then new kind of mercury . The system was very advanced but suffered from practical problems; the explosive squib was dangerous because it was unprotected. In addition, the gun was not gas-tight because of the ignition hole in the bottom. Pauli was not granted success, his student Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse was all the more successful decades later. Dreyses wandering years 1809-1814 took him after completing his training as a locksmith from the Prussian Sömmerda to Paris and there among other things in Pauli's workshop.

Dreyse returned to his father's company in Sömmerda in 1814. He was able to develop an improved manufacturing process for primers and found a successful primer factory on the patent of 1824. Dreyse discovered in 1827 that the detonators used at the time could not only be ignited by blow but also by stabbing, and from this he developed the idea for a new type of ignition mechanism.

Dreyse then designed his "unit cartridge" and the corresponding rifle prototype, initially as a muzzle loader . After initial rejection by the Prussian military authorities, to whom he had submitted his design, he was able to win advocates and developed several improved prototypes. One of his advocates was the then Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm IV , to whom Dreyse was allowed to personally present the rifle in 1829. In 1833 he was finally able to convince with the grape rifle, so called because of the tube end in the form of a grape, and secure an order for 1,100 pieces. Two battalions were equipped with these rifles for extensive testing. Since the grape rifle was rejected as unsuitable, Dreyse designed the cylinder rifle in 1835, in which the ignition device was housed in a cylinder, the little castle.

While the cartridge and ignition device were basically completely developed, the design of the muzzle loader proved dangerous when the cartridge was loaded, as unwanted ignitions occurred again and again. In one such incident, Dreyse injured his hand. For this reason, Dreyse developed a movable bolt in 1836 - the pioneering chamber or cylinder bolt through which the weapon could be loaded from behind. His sniper rifle named resulting design was in principle the later production model, but still had to go through some improvement loops in order to be recognized as mature.

Mass production and use

After successful trials by the Prussian army, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, as King of Prussia, placed an order for 60,000 rifles in 1840. In order to be able to manufacture the weapon in large quantities, Dreyse built a factory in Sömmerda with the help of state loans . Production started slowly; the rifles were stored in the Berlin armory. The name "light percussion rifle M / 41" was chosen for camouflage. In the March Revolution of 1848, rebellious Berliners conquered the armory, which resulted in a number of needle guns falling into their hands. In the period that followed, some rifles made their way abroad. In 1848 the needle gun was first given to a Prussian fusilier battalion . The first use took place in 1849 when the uprisings during the German Revolution were put down, first in Dresden , then in the Palatinate and Baden as well as in the Schleswig-Holstein War . The weapon thus proved its practical capability and Friedrich Wilhelm IV ordered its introduction to the entire army. Since the factory in Sömmerda was unable to meet the high demand (only 45,000 rifles were manufactured by 1848), Dreyse agreed that state factories should also manufacture the needle guns. This happened for the first time in 1853 in the Royal Prussian Rifle Factory in Spandau , then also in Danzig , Saarn and Erfurt . Production became more industrial and efficient over the years using modern means such as lathe and milling machine , which allowed an increase in production. In Spandau, for example, 12,000 weapons were initially produced annually, which was increased to 48,000 in 1867. In 1855 the rifle was officially called the fuse needle rifle . In the course of time, different versions of the needle gun were developed for different applications such as hunters or cavalry . The weapon was also procured from various small German states that were under Prussia's sphere of influence.

The rifle was used in the German-Danish War in 1864, the assessment remained inconsistent. This was due to the fact that only minor skirmishes were conducted in the open field in this war , as most of the fighting was in defense or storming of fortifications. It also happened that some Prussian units had wasted their ammunition in skirmishes . The critics of the needle gun repeatedly warned against this problem. Given their numerical superiority, the Prussians were able to replace these units with ammunitioned ones; with an equal opponent, however, that would not have been so easy.

Only the Prussian successes in the German war - especially in the decisive battle of Königgrätz - in 1866 against the Austrians convinced other states of the advantages of rifles with rear loading. In this war the needle gun acquired its special reputation. However, the technology was only part of the success, because the Prussian Field Marshal Moltke converted the properties of the needle gun into a new tactical concept. Instead of an assault with bayonets attached , the attack should be carried out with rapid rifle fire. The solid, tightly packed formations were given up in favor of a more relaxed formation of smaller units. This reduced the risk of shooting one's own comrade in the back. In addition to the usual salvo , in which the soldiers of a unit fired at the same time, there was also the "rapid fire", in which each individual soldier had to shoot as fast as he could load. The new tactic has been criticized as dishonorable by conservative militaries like Friedrich von Wrangel, as it avoided face-to-face combat. Prussia also invested significantly more in the training of every soldier. The shooters learned to use the sight in order to compensate for the little rapid trajectory of the projectiles (a negative property of the needle gun). The Austrians could not adapt to the needle gun and the tactics of the Prussians. Ultimately, not only the armament, but also the educational, organizational and tactical inferiority of the Austrians were decisive for the outcome of the war.

In France, Italy and Russia and other countries, the ignition needle principle was tested and improved through independent solutions. The Prussians tried to reduce the deficiencies of their technically outdated weapon in order to bridge the time for the planned next generation of rifles. From 1869 an adaptation was started after the proposal of foreman Johannes Beck of the Royal Prussian Rifle Factory in Spandau in order to get the inadequate gas tightness under control (see adaptation according to Beck ). A modified paper cartridge was part of the conversion. At the beginning of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, however, only a few units were equipped with the modified needle guns. Due to the uniform ammunition equipment with the old ammunition, these units had to exchange the retrofitted weapons again. During the course of the war, the needle gun proved to be inferior to the French Chassepot rifle, also a gun with needle ignition, which was constructed over 20 years later. The Chassepot rifle had a longer range than the Prussian needle gun. This enabled the French to inflict heavy losses on the German troops from a great distance. The Germans were forced to approach the French lines under fire until the difference in range was evened out. This increased the importance of the German artillery , which was superior to the French, in preparing for the infantry attack.

After the war, the modification was resumed and the needle guns remained in service until 1876, before the M / 71 rifle , a breech-loader with a single metal cartridge, was issued to the entire force. The cylinder lock of the needle gun was further developed and remained the prevailing locking system for decades until the self-loading rifle appeared .

Working principle

The Dreyse needle rifle contains three major innovations in weapon technology at the time:

- The cartridge contains projectile, propellant and primer as a unit. The lead bullet (2 in the picture) sits in a cardboard sabot (3). The ignition means (4) is located below the sabot, the black powder propellant charge (5) is below it. The components of the cartridge are held together by a strong paper sleeve (1).

- The cartridge is loaded into the barrel from behind ; the gun is a breech loader. The movable chamber is pressed firmly against the pipe and thus sealed gas-tight to the rear.

- Unlike the externally mounted stone - or percussion lock , is the castle within the weapon (internal ignition). The ignition takes place with an ignition needle, which is driven into the cartridge by a tensioned coil spring when the trigger is pulled. The long firing needle must first pierce the paper sleeve and the propellant in order to get to the primer.

technology

The firing needle rifle consists of the main parts barrel, unloading stick, lock and stock . The outer shape largely corresponds to the state of weapon technology at that time.

The shaft is made of walnut or maple wood . The union of the barrel and shaft is achieved by brass rings. A bayonet can be attached to most variants. The steel unloading stick is attached below the barrel. It is used to push a cartridge out of the chamber - for example after a failure in ignition - and serves as a cleaning stick when cleaning the rifle .

Run

The barrel was initially made from the wrought iron customary at the time . Later, the then modern cast steel , which was of a higher quality , was used for the first time in the manufacture of military weapons . In both cases, the barrel was forged from semi-finished products such as sheet metal or billets and then drilled out (see barrel manufacture ). It consists of the chamber and the rifled part. Four trains with a twist angle of 3 ° 45 'are cut into the drawn part of the barrel. There is a thread around the chamber, with which the barrel is firmly connected to the chamber case. At the end of the chamber is the conically shaped mouthpiece, which leans against the sliding chamber and thereby closes the barrel towards the rear.

lock

The technical innovation of the needle gun was the lock that closes the barrel to the rear and houses the internal mechanism for igniting the cartridge. The basis of the construction are three hollow cylinders pushed into one another, the chamber sleeve, the chamber and the lock.

Chamber sleeve

The chamber sleeve (No. 2 in the illustration) accommodates all lock parts and provides the connection with the barrel (1) and the shaft. In its front part is the internal thread for the barrel, behind it the cartridge insert. The cutouts on the top of the chamber sleeve guide the chamber stem (4) of the chamber (3). First, a slightly inclined incision ensures that the chamber is pressed against the barrel when the chamber stem is pressed down, then the incision follows up to the so-called knee, which stops the backward movement of the chamber stem during the loading process, and then to the incision to pull the chamber out completely.

chamber

The chamber (3) closes the barrel and accommodates the inner lock parts. The screwed-in needle tube (11) always guides the ignition needle (7) in the direction of the core axis. There is a free space around the front part of the needle tube called the air chamber. This should promote the combustion of the paper core and absorb combustion residues, but was disadvantageous and unnecessary overall. The front part of the chamber closes the barrel with the chamber mouth. The chamber stem is attached to the chamber and the chamber can be moved by the shooter via this in the chamber case. The rear part takes the lock (6).

Castle

The lock (6) is used to hold some lock parts, to guide the movements of the pin bolt (7) and in interaction with the locking spring (5) and the chamber to cock and relax the rifle. It consists of two main cylindrical parts; In the front the needle bolt moves limited by the two needle bolt heads, in the rear the coil spring (8) is compressed during tensioning. The coil spring causes the ignition needle to jump forward. The hole for the needle head is in the bottom of the castle. The ignition needle can thus be replaced without having to dismantle the lock. The locking spring (5) holds the needle bolt with the helical spring in the lock through the shoulder and the lock in the chamber through its tension and the two lugs. With the help of the locking spring handle, it can be pressed down and disengaged to release the gun. The needle bolt takes the ignition needle. In the rear part is the nut thread for the ignition needle, in front the leather plate bearing. The two needle bolt heads serve to guide the movement of the needle bolt together with the ignition needle. The leather plate blocks the powder gases from the inner lock parts. The ignition needle causes the ignition pill to ignite by pricking it. It consists of the needle, the shaft and the head with thread, through which it is attached to the needle bolt. The needle is made of steel and is soldered into the shaft and this also into the head; the shaft and head are made of brass.

Deduction group

The trigger spring (10) is used to hold and push the lock. The trigger tongue (9) moves the trigger spring. This goes into the pressure piece with the three pressure noses. The shot is released by cocking the trigger. When the trigger tongue is fully depressed, the chamber is unlocked and pulled out of the chamber sleeve.

Accessories and spare parts

The most important accessories are chamber and needle tube cleaners. These also serve as tools, for example for changing the ignition needle. Ignition needles, coil springs and leather plates are important spare parts . These were carried by the soldiers in action.

cartridge

The unit cartridge had a 31 gram pointed bullet ("long lead"), which was provided with three grooves. The connection to the cartridge case was made by a cotton thread which was tied around one of the grooves. The charge consisted of 4.9 to 5 grams of black powder. The total weight was 40 g.

Charging process

The loading process with the necessary movements of the shooter takes place as follows:

1. Relaxing the castle

- The thumb presses the locking spring handle down, thereby the rear lug of the locking spring comes out of the chamber detent and it is possible to pull back the lock with the thumb stud. This movement brings the rear needle bolt head to the trigger spring cleat, which is forced to give way by a slight increase in the applied force. If the rear needle bolt head is pulled over the trigger spring cleat, the latter re-enters the interior of the castle. A complete pulling out of the lock, for example for cleaning, is prevented by the front nose of the locking spring. By pulling back the lock, the needle goes back so far that only its tip protrudes from the mouth of the needle tube.

2. Open the chamber

- A blow of the right hand on the button from below leads the bolt stem from the inclined surface into the case slot and turns the bolt so that the trigger spring cleat comes into its length slot. By pulling the bolt back to the knee, the barrel is opened and the cartridge insert is free.

3. Insert the cartridge

- The cartridge is pushed into the chamber through the cartridge insert. The cartridge must be pushed all the way forward into the chamber with the thumb to prevent it from jamming when the chamber is closed later.

4. Close the chamber

- The chamber is pushed forward with its end face up to the end face of the barrel by means of the chamber stem and the chamber stem is turned into an inclined surface. With a strong blow on the chamber stem, it is pressed onto the inclined surface. This has the effect that the two end faces of the chamber and the barrel are pressed together and thus close the barrel towards the rear.

5. Tensioning the castle

- The lock is pushed into the chamber by pressing on the rear surface of the thumb stud until the rear locking spring nose engages in the chamber catch. The needle bolt - with its rear head supported against the trigger spring cleat - remains standing, so it emerges with the needle head and the rear end of its shaft from the hole in the bottom of the castle. The coil spring is pressed through the bottom of the lock onto the fixed rear pin head and thus tensioned.

Launch process

To fire, the index finger pulls the trigger tongue back until the trigger spring stud is pulled out of the lock so that the rear pin head is no longer blocked. The tensioned coil spring relaxes and drives the needle bolt, which is no longer held up by the trigger spring cleat, with its front head up to the rear end of the needle tube. As a result, the needle slides through the needle tube and its tip pierces first the paper shell of the cartridge, then the propellant powder, in order to finally penetrate the squib and ignite it. The squib then ignites the propellant powder and the combustion gases drive the sabot and the projectile out of the barrel.

Evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages

The needle gun was introduced around the same time as rifled muzzle-loaders, often the Minié system , from the middle of the 19th century. The advantages and disadvantages of the needle gun as a breech loader compared to the rifled muzzle loader were discussed by the military experts.

advantages

Traditional military officials saw a great advantage in the easier cleaning of the barrel with access from both sides. The muzzle-loaders of the time became so encrusted after 25 to 30 shots that loading was no longer possible. However, the problem was no longer so serious with towed muzzle-loaders with the Minié system.

With a breech-loader, the risk of accidental multiple or incorrect loading was much lower than with a muzzle-loader. This occurred again and again with muzzle-loaders in combat under stress and could be fatal for the shooter. Other minor advantages were the protection of the trains while they were running, since no plugging with an iron ramrod was required, and they were less sensitive to wet weather.

The decisive advantages, however, were the possibility of reloading while lying down and the higher firing frequency. Due to the reloading while lying down, the shooter equipped with the needle rifle offered a significantly smaller target area than the shooter with a muzzle loader. With a muzzle loader, the shooter had to stand or at least kneel. The firing frequency of the needle rifle was around three to five rounds per minute under combat conditions - depending on whether volley fire or free firefight - and on the firing range even up to twelve rounds per minute. This means that it is roughly three times higher than that of a Minié muzzle loader.

At the beginning, however, the high rate of fire was seen as a risk of wasting ammunition. With the rapid rate of fire, a soldier could use his entire supply of 60 cartridges in about twelve minutes.

disadvantage

A major disadvantage of the needle gun was its poorer hit performance and range compared to other rifled rifles. Against mass targets , the range was around 600 meters, whereas individual targets could only be hit up to around 200 meters with a high degree of probability. For example, the Austrian towed muzzle loaders of the Lorenz type had a range of around 750–900 m. The French Chassepot rifle - a drawn breech-loader - even had a range of 1200 meters.

Several design flaws were responsible for the poorer shooting performance:

The not very tight closure let some of the powder gases escape. The air chamber collected combustion residues, but led to an unfavorable relationship between the amount of powder and the combustion chamber; thus no high gas pressure was achieved. Holding on to the traditionally large caliber proved to be a disadvantage, although a reduction in the caliber was recommended at that time. Due to the sabot, the lower caliber bullet did not have the barrel caliber of 15.43 mm, but 13.6 mm was still ballistically disadvantageous. The caliber of the French Chassepot rifle , constructed around 20 years later, was only 11 millimeters.

The complicated and therefore error-prone production of the unit cartridge also had a negative effect on the accuracy and range. In about 10% of the cartridges, the bullet was not precisely aligned in the sabot. With some cartridges, the projectile and sabot were separated too late or not at all. Both led to staggering movements and slowed trajectories.

The slide was stiff, especially when the gun was hot. To open and close it, a strong blow of the hand on the stem of the chamber was necessary, which caused pain after several repetitions. So it sometimes happened in combat that stones picked up were used for striking, which in turn could damage the rifle.

The squib was in the middle of the cartridge, which on the one hand minimized the risk of accidental ignition. On the other hand, therefore, the ignition needle had to be long and thin and, after ignition, it was located in the middle of the hot explosion gases. This led to rapid material fatigue and thus to bending or breaking of the ignition needle.

The more complicated production compared to muzzle-loaders was also seen as a disadvantage.

The construction defects persisted until the end of production; only optimizations to the ammunition and a shortening of the air chamber in later models were made. Only at the end of the product life cycle was the Beck adaptation (see below ) carried out, which corrected some defects.

variants

- M / 41 needle gun

- Original model, which served as the basis for other variants. The sighting device has been adapted for the improved M / 47 and M / 55 cartridges.

- Ignition needle sleeve M / 49

- The clasp has been shortened from 25.3 cm to 15 cm. The air chamber was cut in half and now called the compression chamber. The locking surfaces were shaped differently, but this was of no advantage, as powder gases escaping were no longer deflected from the shooter's face. The sights were also changed. The weapon was introduced in small numbers to the Guard Rifle Battalion and Guard Jäger Battalion in order to subject various changes to a troop test.

- Ignition needle barrel (pike barrel) M / 54

- From this model onwards, the barrel was made of cast steel. The closure was shortened to 17 cm. The unloading stick could be extended and locked and served as a triangular pike bayonet. For the first time on a Prussian rifle, the sights were labeled with distance numbers. Introduced into Jäger Battalions and the Prussian Navy .

- Ignition needle carabiner M / 55 and M / 57

- Much shortened to be used as a carbine by cavalry units , the dragoons and hussars . There was no bayonet mount. The cartridge was different from other needle guns; it was shorter and thus contained a smaller amount of propellant charge to make the recoil more controllable. The two variants M / 55 and M / 57 differ only in the barrel. The barrel of the earlier variant M / 55 is made of cast steel, the barrel of the later variant M / 57 is made of steel.

- M / 60 fusilier rifle

- Barrel shortened by 12 cm compared to M / 41. There were two shafts that differed in length by 2 cm. Introduced to fusilier regiments including the guard fusilier regiment

- M / 62 needle gun

- The M / 62 needle rifle replaced the M / 41 as the standard rifle. Compared to the M / 41 it differed in a barrel shortened by 6.5 cm, an improved sighting device and two stock versions like the M / 60 fusilier rifle.

- Ignition needle sleeve M / 65

- The variant for the hunter forces had an extra set trigger with adjustable trigger weight . The trigger should lead to more precision with an aimed shot.

- Ignition needle pioneer rifle U / M (modified model)

- This variant for the pioneers was created by modifying the M / 54 firing needle barrel in 1865. The integrated bayonet was removed, a bayonet holder was attached and the barrel was shortened.

- Ignition needle pioneer rifle M / 69

- New production based on the model of the U / M ignition needle pioneer rifle with only minor differences.

| model | bayonet | Visor up (step (m)) |

Length (m) | Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firing needle rifle M / 41 (for cartridge M / 47) | Socket bayonet M / 41 | 600 (452) | 1.43 | 4.9 |

| Firing needle rifle M / 41 (for cartridge M / 55) | 700 (527) | |||

| Ignition needle sleeve M / 49 | Deer catcher M / 49 | 600 (452) | 1.25 | 4.7 |

| Ignition needle sleeve M / 54 | integrated | 800 (603) | 1.25 | 4.5 |

| Ignition needle carabiner M / 57 | - | 300 (226) | 0.81 | 2.9 |

| M / 60 fusilier rifle | Fusilier side rifle M / 60 | 800 (603) | 1.31 | 4.7 |

| M / 62 needle gun | Nozzle bayonet M / 62 | 700 (527) | 1.34 | 4.8 |

| Ignition needle sleeve M / 65 | Deer catcher M / 65 | 900 (678) | 1.25 | 4.6 |

| Ignition needle pioneer rifle U / M | Pioneer fascine knife M / 65 | 300 (226) | 1.10 | 3.7 |

| Ignition needle pioneer rifle M / 69 | Pioneer fascine knife M / 69 | 300 (226) | 1.11 | 3.9 |

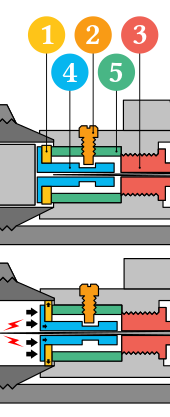

Adaptation to Beck

The M / 60 firing needle rifle, M / 62 firing needle rifle, M / 65 firing needle rifle and M / 69 firing needle rifle were adapted to the Beck system from 1869 . This was suggested by foreman Johannes Beck to the Royal Prussian Rifle Factory in Spandau in order to improve the gas seal. The Chassepot rifle, from which the principle of sealing was adopted, served as a model. The rigid, protruding needle tube (3 in figure) was shortened, a hollow cylinder (5) was inserted into the air chamber and a new, somewhat movable, punch-like needle tube (4) was installed. There is a rubber ring (1) behind the metal plate of the needle tube. When fired, the gas pressure pushes the needle tube backwards against the hollow cylinder and compresses the rubber ring, which widens and seals the chamber. At the same time, handling has been improved. On the one hand, there was no need to manually push the cartridge into the chamber, as the new needle tube does this automatically when the chamber is closed. On the other hand, the ramp-like surface on the chamber sleeve, which caused the closure to be tightened firmly, was no longer required and so the chamber can be opened and closed much more easily; the previously required blow with the ball of the hand on the bolt handle could be omitted. The new ammunition had a 10 grams lighter, ballistically cheaper projectile with a diameter of 12 instead of 13.6 mm; the powder load of 4.9 to 5 g remained the same. The changes resulted in a doubling of the range to around 1200 m, which corresponded to the performance of the Chassepot rifle. In addition, every man could be given 95 cartridges instead of the previously possible 75 cartridges.

Other needle guns from Dreyse

Dreyse was involved in the production of other needle guns. Since Prussia wanted to be prepared for a war with France, at least 80,000 old muzzle-loading rifles, such as captured Lorenz rifles, were converted to the fuse mechanism in the years 1868–1871. The system of needle guns was also used in hunting rifles with the most varied of modifications. However, there were also weapons that were significantly different from rifles. The M65 needle pistol and the needle revolver, introduced in the Prussian army, were produced as handguns. The Dreysesche ignition needle wall rifle M65 also works according to the same principle, but has a significantly larger caliber of 23.5 mm and also differs in the breech and lock.

literature

- Wolfgang Finze, Prussian Zündnadelgewehre: Guide for aspiring collectors and shooters, Books on Demand 2016, ISBN 978-3739201085

- Sebastian Thiem: Traditional with modern. The side guns for the needle gun 1841. In: DWJ (formerly Deutsches Waffen-Journal) 5/2014, pp. 94–99.

- Wolfgang Finze: needle test. Shooting with the needle gun . In: visor . tape 5 , 2014, p. 52-59 .

- Georg Ortenburg: Weapons of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871 . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 2005, ISBN 3-8289-0521-8 .

- John Walter: Rifles of the World . Krause Publications, Iola WI 2006, ISBN 0-89689-241-7 , pp. 102-106 ( online ).

- Werner Eckhardt, Otto Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945 . HG Schulz, Hamburg 1957.

- Heinrich von Löbell : The history of the needle rifle and competitors: Lecture given at the meeting of the military society in Berlin on November 30, 1866 . Mittler-Verlag , Berlin 1867 ( online ).

- Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War: Austria's War with Prussia and Italy in 1866 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, ISBN 0-521-62951-9 ( online ).

- Manfred R. Rosenberger, Katrin Hanné: From powder horn to rocket projectile: the history of small arms ammunition . Motorbuch-Verlag, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-613-01541-2 , p. 71-72 .

- Rolf Wirtgen : The needle gun. A military-technical revolution in the 19th century . Ed .: Defense technology study collection of the Federal Office for Defense Technology and Procurement. Mittler, Herford u. a. 1991, ISBN 3-8132-0378-6 (exhibition catalog).

- Wilhelm von Ploennies : New studies on the rifled firearm of the infantry: The ignition needle rifle: Contributions to the criticism of the rear-loading weapon . Zernin, Darmstadt u. a. 1865 ( online ).

- Needle gun . In: Pierer's Universal Lexicon . tape 19 . HA Pierer, Altenburg 1865, p. 729-730 ( online ).

- Article in Polytechnic Journal .

- Anonymous: The Prussian needle gun. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 123, 1852, pp. 91-103.

- Henry Darapsky: English and American communications about the Prussian needle gun. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 183, 1867, pp. 8-13.

- Anonymous: The adapted needle gun. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 196, 1870, pp. 426-429.

- Anonymous: War weapons at the exhibition in Antwerp and related items. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 294, 1894, pp. 193-199.

- Karl von Helldorff: Buschbeck's Prussisches Feld-Taschenbuch for officers of all weapons for war and peace use . Hempel, Berlin 1869, p. 17-28 ( online ).

Web links

- Board of Trustees for the Promotion of Historical Weapons Collections: Fuse Gun M / 41 , Fuse Gun M / 54 , Fuse Carabiner M / 57 , Fuse Gun M / 62 , Fuse Pioneer Rifle M / 69

- Pike bayonet M54 for Dreyse ignition needle pike rifle M54 at hw-loevenich.de

- Grape rifle 1834 at progun.de

- schmids-zuendnadelseite.de

- Description of the ignition needle system with pictures at feuerwaffen.ch (PDF)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b M. R. Rosenberger, K. Hanné: From the powder horn to the rocket projectile. 1993, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Ploennies: New Studies on the Rifled Firearm of the Infantry. 1865, p. 23.

- ↑ Loebell: The needle gun's history and competitors. 1867, pp. 11-13.

- ↑ Ploennies: New Studies on the Rifled Firearm of the Infantry. 1865, p. 29.

- ↑ Loebell: The needle gun's history and competitors. 1867, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ Ploennies: New Studies on the Rifled Firearm of the Infantry. 1865, p. 32.

- ↑ MR Rosenberger, K. Hanné: From the powder horn to the rocket projectile. 1993, p. 72

- ↑ Ploennies: New Studies on the Rifled Firearm of the Infantry. 1865, pp. 33-35.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Ortenburg: Weapons of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 60.

- ↑ Loebell: The needle gun's history and competitors. 1867, p. 42.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Loebell: The needle gun's history and competitors. 1867, p. 48.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War. 1997, pp. 34-35.

- ^ A b Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War. 1997, p. 23.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Wilhelm Riistow : The war around the Rhine border 1870. Schulthess publishing house, 1870.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War. 1997, pp. 22-24.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War. 1997, p. 130.

- ↑ Geoffrey Wawro: The Austro-Prussian War. 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Peter Broucek , Erwin A. Schmidl : Military, History and Political Education. Böhlau, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-205-77117-6 , pp. 331-332.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 61, 65.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 131.

- ^ MR Rosenberger, K. Hanné: From the powder horn to the rocket projectile: the history of small arms ammunition. 1993, p. 74.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 63.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 181, 183, 186.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 131-132.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 57-59.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Pierer's Universal Lexicon. Volume 19, 1865, pp. 729-730.

- ↑ Common name at the time. Not to be confused with modern cast steel .

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 116-117.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 112-114.

- ↑ a b Ortenburg: Weapons of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 59.

- ↑ a b W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of Brandenburg-Prussian-German army from 1640 to 1945 . 1957, p. 114.

- ↑ Anonymous: The aptirte needle gun. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 196, 1870, pp. 426-429.

- ↑ a b W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of Brandenburg-Prussian-German army from 1640 to 1945. 1957, p. 103.

- ^ Author collective: Prometheus, Volume 29. Mückenberger, 1917, p. 158 ( at Google-books )

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 145.

- ↑ a b Ortenburg: Weapons of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 60, 145.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 102

- ↑ Jan Ganschow, Olaf Haselhorst, Maik without time (ed.): The Franco-German War 1870/71. Ares-Verlag, Graz 2009, ISBN 978-3-902475-69-5 , p. 231 ( at Google-books )

- ^ Karl Heinz Metz : Origins of the future: the history of technology in western civilization. F. Schöningh, Paderborn 2006, ISBN 3-506-72962-4 , p. 402 ( on Google books )

- ↑ By Berthold Seewald: Pickelhaube - symbol for Prussian militarism . In the world . dated February 15, 2011, last accessed on September 27, 2014.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 144.

- ^ Theodor Fuchs: History of the European war system. Volume 3, Lehmann, 1972, p. 78 ( on Google books )

- ^ Hans Meier-Welcker : Handbook on German Military History, 1648-1939. Volume 9, Bernard u & Graefe, Freiburg i. Br. 1979, p. 335 ( at Google books )

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 116.

- ↑ a b W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of Brandenburg-Prussian-German army from 1640 to 1945. 1957, p. 107.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 108-109.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 115.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 108, p. 116.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 130.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 118.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 120-121.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 121-122.

- ↑ a b W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of Brandenburg-Prussian-German army from 1640 to 1945. 1957, p. 126.

- ^ Walter: Rifles of the World. 2006, p. 104.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 122-123.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 123.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, p. 124.

- ^ Walter: Rifles of the World. 2006, p. 105.

- ↑ a b W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of Brandenburg-Prussian-German army from 1640 to 1945. 1957, pp. 125-126.

- ^ Walter: Rifles of the World. 2006, pp. 102-105.

- ↑ Anonymous: The aptirte needle gun. In: Polytechnisches Journal . 196, 1870, pp. 426-429.

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, pp. 62-63, 68.

- ^ Reinhold Günther: General history of small arms. Leipzig, 1909, Johann Ambrosius Barth Verlag , p. 64 [1]

- ^ Walter: Rifles of the World. 2006, pp. 105-106.

- ^ Sarah Evans: Henry's Attic: Some Fascinating Gifts to Henry Ford and His Museum. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 1995, ISBN 0-8143-2642-0 , p. 238 ( in Google books )

- ↑ Ortenburg: Arms of the Wars of Unification 1848–1871. 1990, p. 70

- ^ W. Eckhardt, O. Morawietz: The hand weapons of the Brandenburg-Prussian-German army 1640-1945. 1957, pp. 127-130