Dry Creek explosives store

The Dry Creek explosives store was a hazardous material store near Port Adelaide in Australia . Operated from 1903 to 1995, it stored civilian explosives primarily for mining and construction . Several storage sheds and a jetty belonged to the camp . The jetty and the storage shed were connected to the long-distance railway network via a narrow-gauge railway . The camp is a witness to the economic history as well as the transport system in South Australia and became the 1994 cultural monument appointed.

prehistory

The government of South Australia saw the control of explosives as a sovereign task . This also included the storage of large quantities of explosives.

The storage of explosives in the port of Adelaide took place from 1858 in the North Arm Magazine on Magazine Creek near Gillman , south of the North Arm of the Port River under the responsibility of the transport authority of South Australia, the Marine Board. It replaced the previous deposit on the LeFevre Peninsula. From the start, North Arm Magazine has been criticized for its proximity to docks and residential buildings, and therefore a potential hazard. In the late 19th century the volume of explosives multiplied; the reason was mainly the growing mining in Broken Hill . Additional storage space has been created on Hulks in Port Gawler , approximately 20 km north of Port Adelaide . This measure was unpopular with the explosives dealers, since the transport for loading was expensive and tedious because of the tide changes . Years of debates followed about the shape (on land or water) and the location of a future explosives store. Finally, in 1899, the Marine Board decided to move to the remote location on Dry Creek, 6 km east of the port, to build a warehouse with increased capacity. North Arm Magazine was demolished in 1916.

camp

Storage area and storage shed

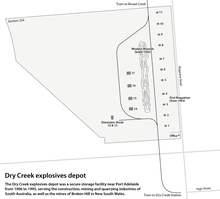

The camp site originally covered 124 hectares and was inland of a mangrove swamp between Dry Creek and Port Adelaide, on Broad Creek, which branches off from the North Arm and leads in the direction of the village of Dry Creek.

The first buildings, eight explosives storage sheds (No. 1 to 8) with a capacity of 20 t each , were completed on November 25, 1903. In the following year, a double shed (No. 12 & 13), which was dismantled by the North Arm Magazine, for the storage of detonators and two more explosives storage sheds (No. 9 & 10) were built. Earth walls surrounded the storage sheds on three sides. You should protect neighboring scales if one of the scales should explode. The budget by then was £ 6,000 to £ 7,000. Additional buildings were added in the years that followed: an examination shed in 1907 (No. 11), two 30-ton warehouses (No. 14 & 15) in 1915 and two 20-ton warehouses (No. 16 & 17) in 1919. There was an office building at the entrance to the camp.

The construction of the storage shed probably goes back to the explosives company Nobel Industries from Ardeer (Scotland) . A similar explosives warehouse was built in Robb Jetty near Perth as early as 1900.

At the end of the 19th century, the principle of storing explosives was to offer as little resistance as possible to an explosion ( containment ). The storage sheds were therefore built using lightweight construction. Care was taken to protect the explosives from heat, moisture and dust. The basic form was one-story with a double hipped roof with a large overhang ; the buildings were built on a foundation of Jarrah piles. The structure consisted of a wooden frame . The walls were made of two layers of galvanized corrugated iron with an air space in between; On the inner corrugated iron, wooden plank cladding was attached by means of battens, so that there was also an air space there. The triple wall construction, each with an air space in between, and the shape of the roof ensured good thermal insulation . The sheds were naturally ventilated . A large ventilation shaft led from a prominent lantern through the double roof into the interior; There were also ten ventilation shafts in the floor . This allowed cool air to be drawn in from below the building. The ventilation shafts and ducts were covered with metal grids to keep out dust and sparks. The outer walls of the storage shed were whitewashed. Originally there were rainwater tanks in front of the storage shed, but these were removed when the narrow-gauge railway was relocated.

6,000 trees, mainly tamarisks , were planted on the camp grounds . They should provide shade and thereby improve the microclimate and, as additional protection, weaken a detonation wave.

Jetty

The jetty was built on Broad Creek, 2 km north of the camp. Because of the changing tides, there were various mooring options at low and mean tide . In 1917 a Hulk was aground there to stabilize the pier. At first it was used as an additional storage area, but from 1938 it was increasingly demolished for replacement material. The remains are still visible today.

During the highest flood ever registered up to July 1917, the pier, which was 3.6 m above the low water level, was washed away. In 1934, parts of the jetty, which had been severely weakened by shipworm infestation and neglected maintenance, had to be repaired.

Horse train

In 1906 a field railway with a gauge of 762 mm (2 feet 6 inches ) was built. It ran along the storage shed and connected it on the one hand over a distance of 2 km (1 ¼ miles) to the ship landing and on the other hand over a distance of 800 m (½ mile) to the Dry Creek train station. Six specially constructed narrow-gauge trucks, each holding 1 ¼ t, were available. They were drawn by horses. Until then, the explosives had been brought across the street from the dock on the North Arm to the storage sheds, which was not only expensive but also dangerous.

To make it easier for the horses to move forward, the spaces between the railway sleepers were initially filled with local shell sand. This, however, was of sheep to keep, which were allowed to graze in the area around the grass low and thus the wildfire danger to lower trampled to dust. The shell sand was then replaced with slag , a by-product of the purification of steam locomotives at Dry Creek Station and nearby industrial facilities.

The horse-drawn railway operated until 1965 when a truck was purchased to replace it . The rails in the warehouse and to Dry Creek station were dismantled. The lorries were donated to the Illawarra Light Railway Museum in 1978 , where they are on display today.

business

The camp started operations in December 1903. Explosives from North Arm Magazine and Port Gawler were transported here. This was initially done by land, and from January 1906 on with the narrow-gauge railway. That month, the first cargo was picked up via the Broad Creek pier.

Seagoing vessels loaded with explosives were unloaded in the Gulf Saint Vincent before they were allowed to enter Port Adelaide . The explosives were on Easy transhipped, these were from motor launches drawn to Broad Creek. The camp had several of its own barges. Again and again it happened that the storage capacity was insufficient, so the explosives were temporarily stored on the barges on Broad Creek.

Strict safety regulations should prevent catastrophic explosions. They were particularly aimed at preventing the formation of sparks , which can be triggered by the friction of metals and some types of rock. So either special shoes without nailed soles or overshoes had to be worn and care was taken that as little sand as possible got into the storage sheds.

The Chairman of the Marine Board, Arthur Searcy , inspected the newly constructed explosives store on June 19, 1906. Each shed could actually store 40 tons of explosives, but at the time of the inspection the maximum amount was limited to 20 tons. The inspection found that the arrangements for transporting and storing the explosives had been improved compared to before. The necessary precautions to prevent explosions were in place, and printouts of the guidelines were pinned to the front doors.

The camp personnel were also responsible for destroying unsafe explosives. It happened by burning or dumping in the ocean.

Much effort was required for the maintenance of the facilities because the swamp was flooded regularly. The narrow-gauge railway line from the landing stage to the warehouses was damaged several times by the flooding and had to be lifted and repaired again and again. In August 1917 there was an extraordinarily high flood that washed away all of the workers' equipment.

Other types of flooding were also uncomfortable for the camp workers. A sewer ran adjacent to the property and flowed into North Arm Creek. The canal put in tons of foul-smelling debris. In 1922, a dam to the sewer was built on the site of the explosives storage facility. The situation only improved over the years through improved sewage treatment plants .

Decline

From the end of 1925, the explosives from Victoria were delivered less frequently but in larger batches. This reduced the need for deliveries via the jetty, and the day laborers paid less and less needed.

In the early 1930s, rail and road transport replaced domestic Australian transport via seaports. From 1934 the explosives were delivered from the factory in Deer Park by rail, which became increasingly popular. When the volume of shipments decreased, Broad Creek was no longer regularly dredged. In the 1950s only urgent repairs were carried out on the jetty, but it was not renewed. The last ship delivery of explosives took place in 1970. In 1976 the pier was demolished.

The once remote location was increasingly harassed by civilization. On the initiative of the government to accelerate industrialization , Imperial Chemical Industries installed large salt pans in the north and west of the explosives store from 1936 . The western part of the explosives store, a large part of the camp site including four storage sheds, was leased to the company in this context and separated from the warehouse. In 1936 the blasting capsule shed and in the later 1930s the leased storage sheds were demolished. In 1950, for safety reasons, a long earth wall was built in front of the western side of the storage shed. The growing salt flats were joined by a radio transmitter , power lines and a highway to the south.

From 1978 onwards, ammonium nitrate became an important component of explosives (e.g. ANC explosives ), so that these could be produced on site and, with the improvement of safety regulations, the inspection and storage that was previously necessary became increasingly superfluous.

Cessation of operations

Operations ceased in October 1995 after the warehouse had been underutilized for about 20 years. Eleven of the historic buildings built between 1903 and 1907, ten 20-tonne magazines and an examination shed are present with their earth walls on the shrunk to 20 hectares and were already registered in 1994 under No. 14521 in the Register of State Heritage Items. In 2000 they were in a stable condition, but the steel reinforcement of the concrete piles, which were installed instead of the wooden piles in the 1960s, increasingly rusted in the salty subsoil. Remains of the pier and the narrow-gauge railway are still visible on the seaward side of the salt production plant; the embankment between the camp and the pier is still there but flooded.

Since there was still a need for an explosives store after the closure, mobile containers were first made available on the site of a sewage treatment plant. In 2008 , the modern Pine Lea Explosives Reserve was built near Swan Reach , about 100 km east of Adelaide .

See also

Web links

literature

- Bridget Jolly: A Significant Site: the Former Dry Creek Explosives Reserve in: Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia, No. 29, 2001, ISSN 0312-9640 , pp. 70-84.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Bridget Jolly: High And Dry By The Mangroves? South Australia's Dry Creek Explosives Magazine. First presented at the Fifth Australian Urban History Planning History Conference, University of South Australia, 13. – 15. April 2000 and published in the Conference Proceedings, edited by Christine Garnaut and Stephen Hamnett, University of South Australia, Adelaide 2000, pp. 222-232.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, pp. 71-73.

- ↑ a b c d The Dry Creek Explosives Depot. An official visit. The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1889-1931), Wednesday June 20, 1906.

- ↑ a b c Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, p. 82.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, pp. 75-76, 78.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, pp. 73, 77, 79.

- ^ Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics: Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, No. 11-1918 . Aust. Bureau of Statistics, 1947, p. 756.

- ^ Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics: Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia, No. 15-1922 . Aust. Bureau of Statistics,, p. 597.

- ↑ a b c Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, p. 78.

- ^ A b Ray Clifford: Explosive Storage. EPP & CIE 2012. ( Memento of April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Lecture by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of South Australia, SafeWork SA, on the storage of explosives, presumably presented at the 12th International Conference of Chief Inspector of Explosives on 10-12. May 2012 in Berlin.

- ^ Illawarra Light Railway Museum: Horse-drawn explosives carrying wagons of the Dry Creek Explosive Magazine in South Australia .

- ^ The Dry Creek explosives magazines. The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA: 1889-1931), Wednesday December 30, 1903.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, p. 77.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, p. 80.

- ↑ Jolly: A Significant Site, 2001, p. 70.

- ↑ Chapter 15: Public Service Facilities. In: Report on the Metropolitan Area of Adelaide - 1962 ( PDF file with 22.7 MB ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )), p. 188.

- ↑ Peter Carter: Notes on the Torrens Island and Environs map.

Coordinates: 34 ° 49 ′ 42.9 ″ S , 138 ° 34 ′ 47.5 ″ E