Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( Irish Éirí Amach na Cásca , English Easter Rising ) of 1916 was an attempt by militant Irish Republicans to force the independence of Ireland from Great Britain . Although it failed militarily, it is considered a turning point in the history of Ireland , which ultimately led to independence as an Irish Free State in 1922 .

overview

The uprising took place from Easter Monday, April 24-29, 1916. Part of the Irish Volunteers under Patrick Pearse and the much smaller group of the Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly seized several buildings in Dublin and proclaimed the independent Irish Republic. At the same time, the various resistance groups were merged to form the Irish Republican Army . Although it failed, this armed uprising is considered a turning point on the way to Irish independence, because it created a direct split between the violent Republicans and the more passive nationalists under John Redmond and "his" Irish Parliamentary Party , which through democratic parliamentary work the Approval of the (3rd) Home Rule .

Politically, the uprising only became a success through the decision of the Commander General of the British Forces in Ireland, Sir John Grenfell Maxwell , who had the captured commanders of the Irish Republican Army executed. As soon as the executions became known, the sympathy of the Irish people swung to the side of the Republicans.

Planning the uprising

While the Easter Rising was mainly carried out by the Irish Volunteers (IV), it was planned by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) together with its sister organization in the USA , the Clan-na-Gael . Shortly after the beginning of the First World War on August 4, 1914, the highest-ranking members of the IRB met under the maxim "England's difficulties are Ireland's opportunities" and decided to carry out actions before the end of the war. To this end, the IRB treasurer Thomas James Clarke formed a military committee (originally Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt and Joseph Plunkett ; Seán Mac Diarmada and himself joined shortly afterwards ) to plan the uprising. Each of these people were members of the IRB and, with the exception of Clarke, the Irish Volunteers. The IRB had sought control of the Volunteers since the Irish Volunteers was founded in 1913 by promoting IRB members whenever possible. This resulted in much of the volunteer leadership being violent and devoted Republicans by 1916. An important exception, however, was founder and chief of staff Eoin MacNeill , who was against any high-risk rebellion. The IRB therefore hoped to either pull him on its side (if necessary through fraudulent intent) or to be able to simply bypass him. The IRB had little success with either plan.

The plan for an insurrection took the first major hurdle when the socialist James Connolly, head of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) and completely unaware of the IRB's plans, threatened with an "own" insurrection if other groups did not support independence would fight. Since the ICA was barely more than 200 men strong, any independent uprising would be doomed to failure from the outset, which would also have greatly reduced the chances of an uprising by the volunteers. So the IRB leaders met with Connolly and convinced him to join them. They agreed to work together on the coming Easter.

In an attempt to deceive informants and of course the actual leader of the volunteers, Pearse ordered three-day “maneuvers and parades” of the volunteers from Easter Sunday at the beginning of April. The time was chosen deliberately, since solemn parades on high Christian holidays were by no means unusual and aroused no suspicion. While the real Republicans within the volunteers knew exactly what the real background of the parades was, it was hoped that MacNeill or the British forces at Dublin Castle would take this announcement literally. But MacNeill got wind of the matter. He threatened to do everything possible to prevent this uprising. When MacNeill learned from Mac Diarmada, however, that Germany had promised, Irish-British prisoners of war who had agreed to transport to Ireland and about 40,000 French and Russian booty rifles with an auxiliary ship with the code name Aud in cooperation with SM U 19 am Landing Good Friday in Ireland ( County Kerry ), MacNeill was ready to consent to the uprising. This agreement with Germany was engineered by Sir Roger Casement and the IRB. But this melodious announcement was only half the story. Casement's plans to form a so-called Irish Legion out of Irish prisoners of war with a republican conviction , which were to be trained for partisan warfare in Ireland with the help of German instructors and weapons , had failed miserably. The supply of arms was only granted by the German side to enable at least a brief uprising in Ireland and thus weaken the British home front. A large-scale revolt against British rule was not expected on the German side either. But the landing of the weapons transport also failed because the time and place were poorly coordinated. When MacNeill found out about this, he went back to his original attitude and worked with “friendly” colleagues, including a. Bulmer Hobson and The O'Rahilly , a revocation to all volunteers with the cancellation of all actions on Sunday. Although this led to a greatly reduced number of volunteers in the uprising (approx. 1000), it could not prevent it, but only postpone it by one day. Regardless of the failure of the Libau enterprise, the Imperial Navy led to the support of the uprising on 24/25. April 1916 a bombardment of Lowestoft and Great Yarmouth , in which naval airships were also used against English cities. The planned bombing of London failed due to bad weather conditions.

Even Patrick Pearse was aware that the Easter Rising was tantamount to a suicide command. Some time beforehand he said to his mother: "The day will come when I will be shot and my comrades with me". When his mother asked about her other son, William, also an extreme nationalist, Pearse is said to have replied, “Willie? Shot like the others. We're all shot. "James Connolly is reported to have once remarked:" The odds against us are 1 in 1000. "

The riot

The plan, largely devised by Plunkett (but also very similar to Connolly's independent plan), was to occupy junctions and strategic buildings within Dublin in order to cordon off the city and prepare for the inevitable counterattack by the British Army. Then, it was hoped, one of three scenarios should arise: The Irish nation also rises and supports the attack; the British realize the impossibility of continuing to rule Ireland and withdraw; or - as a last hope - the Germans would somehow come to the aid of the rebels.

Easter Monday

The operation started at noon, and since it was a public holiday, there were larger crowds on the streets to see the smaller groups of volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army marching armed to their locations.

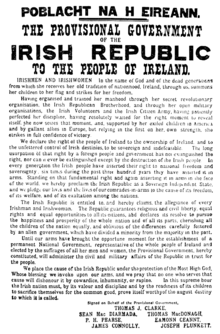

This was followed by the reading of the Easter proclamation outside of the main post office in Dublin on Sackville Street (today: O'Connell Street ), Dublin's main street and the world's widest Georgian avenue . This marked the very beginning of the uprising. After the reading, which was greeted with amazement and a little mockery by people passing by, Pearse and other leaders went to the main post office, took control of it and set up their headquarters there.

Basically, the whole operation went smoothly: five larger buildings or complexes of buildings north of the River Liffey , nine south of it, and some railway stations were occupied.

The Volunteers' Dublin Division was divided into four battalions - each under the command of a loyal IRB commander. A makeshift 5th Battalion was formed from parts of the others and with the help of the Irish Citizen Army. It was this battalion that occupied the Central Post Office in Dublin (GPO). Those included the President and Commanding Officer of the IRB, Patrick Pearse, the Commander of the Dublin Division and Leader of the ICA James Connolly, Thomas James Clarke , Seán Mac Diarmada, Joseph Plunkett and a young captain named Michael Collins . In the meantime, the 1st Battalion under Ned Daly had besieged the Four Courts courthouse and areas in the northwest; the 2nd Battalion under Thomas MacDonagh occupied Jacobs Biscuit Factory south of downtown; to the east, Éamon de Valera commanded Boland's Bakery, and the 4th Battalion under Éamonn Ceannt captured the South Dublin Union building in the southwest. ICA members also occupied St. Stephen's Green and Dublin City Hall under Michael Mallin and Constance Markiewicz , the only woman in leadership positions in the uprising .

The attempt to capture Dublin Castle failed. Another attempt to steal large quantities of guns and ammunition from an arsenal in Phoenix Park was also unsuccessful - only a few weapons were captured. In contrast, the rebels managed to cut telephone lines, so that Dublin Castle was almost isolated for some time.

Since the revocation of MacNeill meant that the uprising took place almost exclusively in Dublin, the command of all rebels involved passed to Connolly, who also had the best tactical understanding of the group. Connolly was badly wounded during the riot, but continued to command his people by letting himself be carried around in a bed. His biggest misjudgment, however, was the assumption that a capitalist government would never use artillery against its own property (read: buildings); within 48 hours the British had convinced him otherwise. Two British gunboats fired at each other, assuming that the impacting grenades came from the rebels.

However, the British took slow action against the rebels, unsure of how many insurgents they were dealing with. They called in troops from the Curragh military camp and other locations outside Dublin, as well as assistance from London . There Lord French, an Irishman and avid Unionist, was in command and sent no fewer than four divisions to Ireland. British politics were turned upside down at the time. The policy of appeasing Ireland was forgotten, it was only a matter of quickly and completely annihilating the rebels. But not only the British were groping in the dark - the rebels had no radio links between their occupied positions either. The rebels (around 1,000 Irish Volunteers and around 200 members of the ICA) faced around 4,500 British soldiers and 1,000 police forces.

Tuesday

From a military point of view, Tuesday was comparatively calm. The British carefully approached the positions to secure the areas and isolate the chiefs in the main post office. Artillery was deployed at Trinity College . Looting by the population began. Tensions within the two groups involved increased when a volunteer officer gave the order to shoot marauders - an order that was angrily revoked by James Connolly. The martial law was imposed on Dublin and the British reinforcements arrived Kingstown. The atrocities of the uprising began when a British officer named Bowen-Colthurst shot and killed three harmless journalists "while on the run".

Wednesday

On Wednesday morning, the rebels were outnumbered 20 to 1 and the British, in turn, began to attack seriously. The first foray was at Liberty Hall . The building, headquarters of the Labor Party and the union, was destroyed by the bombing of the gunboat "Helga". Since the rebels had foreseen this, the building was already empty at that time. The British shelling was very imprecise, so that various other buildings were hit and many civilians were killed. The army now also used artillery, sometimes even against individual snipers. In many places in Dublin there were fire and the Dublin population went hungry due to the lack of food supplies. By this point the insurrection had turned into a real war, with no attempt made to protect civilians and avoid casualties among them. The British support from Kingstown was ambushed by the De Valeras division on their march into the city, suffered heavy losses, but was able to fight their way into the city due to their numerical superiority. There were no more rebels in St. Stephen's Green at that time. The park occupation turned out to be unwise when part of the British Army took up positions at the Shelbourne Hotel, on the northeast corner of the park, from which they could overlook the whole park and even shoot into the trenches. The rebels withdrew to the Royal College of Surgeons and re-established their position there.

Thursday

On the fourth day of the uprising, the new British Commander-in-Chief, Sir John Maxwell, arrived in Ireland. Although he was closely related to Countess Markiewicz , he had no knowledge of the current political situation in Ireland, and so it happened that he (ignorantly) did more to undermine British rule in Ireland than any rebel doer made it together. His order - given by British Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith - was to end the rebellion as quickly as possible. In the end he did - regardless of the political consequences.

Support from England, mostly inexperienced men (many others fought for Great Britain in World War I), was now on duty. When they discovered that many of the men in the Irish Republican Army (as they were to be called from now on) were not wearing uniforms, they began shooting dead civilians they encountered on suspicion.

That day began the attacks on Boland's bakery and the bombing of the main post office, which burned down completely. The Volunteer Division in South Dublin Union lost ground. Connolly was wounded twice that day - the first wound he was able to hide from his men, the second wound, one of his feet was crushed, was too serious for that. But under morphine he continued to command as best he could. Due to the constant bombardment in the streets and the often interrupted water supply, the fires in Dublin combined to form major fires that could no longer be controlled. On Thursday none of the rebel positions had surrendered.

Friday

On Friday Connolly ordered the women among the rebels to leave the main post office, which was now completely isolated and on fire. Later that day, he and the remaining rebels were able to leave the building, which was burning and almost collapsing almost everywhere, unnoticed. They found shelter in a nearby house while the British continued to bomb the empty post office. One last major battle took place on King's Street. It took 5000 British soldiers, armed with armored vehicles and artillery, 28 hours to advance 150 meters against 200 rebels. In this fight, the British South Staffordshire Regiment stabbed civilians and shot people hiding in cellars.

Saturday

On the morning of April 29, the uprising ended. Pearse and Connolly ordered unconditional surrender from their new base on Moore Street after realizing that all that could be accomplished now was the death of more civilians.

Consequences

The victims of the uprising are difficult to gauge. It is believed that around 500 British soldiers lost their lives. The Irish (including civilians) were likely to have twice as many casualties. The material damage within the largely destroyed city was put at 2,500,000 pounds.

At that time, the rebels had little popular support - this was only to change through the reprisals of the British. When the captured rebels were transferred from one prison to another on Sunday, they were led through Dublin on foot, where they were mocked and cursed, especially in the poor areas. A total of 3,000 "suspects" were arrested. Many of them ended up in internment camps in Wales .

On direct orders from the Cabinet in London, the punishment was swift, secret and brutal. The 15 leaders (among them all seven signatories of the Easter Proclamation) were brought before a court-martial and executed by shooting from May 3rd to May 12th. Those executed included Willie Pearse (not actually a leader; it is believed that he was also shot because of his famous brother Patrick Pearse), the sick Joseph Plunkett, and the wounded Connolly, who was shot dead in a chair because he was unable to stand on his own could. The executions were only announced after they were carried out. When this became known, it sparked a wave of indignation across Ireland that did not abate even when Asquith defended these measures in the House of Commons, or when he admitted the mistake and dismissed Commander John Maxwell.

Éamon de Valera saved Glück and his American origins from execution (although he was Irish, he was born in America). This resulted in his execution being postponed. When his execution was finally decided and “it was his turn”, the executions were generally stopped due to public opinion (across Europe). Other people involved were merely arrested, including Michael Collins.

The tough measures after the suppression of the Easter Rising forced the anti-British mood.

For the German war opponents, the intervention in the Easter Rising meant a partial success, as the British were forced to station more troops in Ireland. This led to relief on the western front, especially since the British refrained from using soldiers recruited in France in the south of the island. However, the uprising did not lead to the hoped-for destabilization of Great Britain.

In the December 1918 elections, the Sinn Féin independence movement won 73 of the 106 Irish seats in the House of Commons. In January 1919 Irish MPs met in Dublin to a national parliament ( Dáil Éireann ), declared independence and set up a government under Éamon de Valera, which was not recognized by Great Britain. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). With the Government of Ireland Bill (1920), which provided for one parliament each for Northern and Southern Ireland with limited legal autonomy and regarded the British Parliament as the final instance, the British government under Prime Minister Lloyd George sought , with the price of the partition of the island, to meet the demands for independence.

On July 11, 1921, negotiations with de Valera brought about an armistice and resulted in the Anglo-Irish Treaty on December 6, 1921 . After the adoption of the treaty by the majority of the Dáil Éireann on January 7, 1922, the constitution of the " Irish Free State " on December 6, 1922 came into force. The six majority Protestant counties of Ulster declared by referendum that they wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom as " Northern Ireland ". It was not until April 18, 1949 that Ireland became fully independent from Great Britain.

The uprising marked the birth of the IRA . The Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Sinn Féin are still fighting for the unification of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The rebellion became the model of the Bengali Indian Republican Army (Chittagong Branch) (IRA), which unleashed the Chittagong uprising on Good Friday 1930 .

List of executed leaders

- Sir Roger Casement , executed (by hanging) at HM Prison Pentonville on August 3, 1916

- Thomas James Clarke , executed May 3, 1916

- Éamonn Ceannt , executed May 8, 1916

- Cornelius Colbert , executed May 8, 1916

- James Connolly , executed May 12, 1916

- Edward Daly , executed May 4, 1916

- Seán Heuston , executed May 8, 1916

- Thomas Kent , executed May 9, 1916

- John MacBride , executed May 5, 1916

- Seán Mac Diarmada , executed on May 12, 1916

- Thomas MacDonagh , executed May 3, 1916

- Michael Mallin , executed May 8, 1916

- Michael O'Hanrahan , executed May 4, 1916

- Patrick Pearse , executed May 3, 1916

- William Pearse , executed May 4, 1916

- Joseph Plunkett , executed May 4, 1916

In art

Poetry and literature

William Butler Yeats ' poem "Easter 1916" is an early and literarily significant processing , which characterizes the uprising with the succinct oxymoron "a terrible beauty".

The drama The Plow and the Stars by Sean O'Casey , premiered in 1926 at the Abbey Theater in Dublin, has the Easter Rising as a framework, but is from the perspective of simple, poor people in Dublin the tragic impact of the events on their lives.

In the novel On est toujours trop bon avec les femmes, published in Paris in 1947 , Raymond Queneau describes the struggle for the General Post Office as an erotic grotesque : a postwoman who happens to be present begins - as a survival strategy - to seduce the national Irish heroes one after the other, only to then seduce them to accuse the victorious British of sexual assault. James Connolly and his comrades-in-arms die in the hail of bullets from the firing squad, not as freedom heroes, but trivially as molesters.

The novel A Star Called Henry by Roddy Doyle (1999) deals with the uprising in the second third of the book in an interesting way: the protagonist Henry, a clever street boy from the poorest of backgrounds and 14 years old at the time, is the protégé of James Connolly in the GPO and reports the events from his perspective.

music

Countless songs deal with the Easter Rising and its protagonists. Not only traditional Irish music has taken on the subject with pieces such as "The Foggy Dew" by Charles O'Neill or "James Connolly" and "Padraig Pearse" by the Wolfe Tones , modern Irish music is also repeatedly referred to Referenced events of Easter 1916. The song " Zombie " by The Cranberries deals with the long-lasting consequences of the Easter Rising. A controversial interpretation finds allusions to the Easter Rising in the song Sunday, Bloody Sunday by U2 .

Movie

The uprising was also discussed again and again in the film. As early as 1936, John Ford made an adaptation of The Plow and the Stars of the same name . In 1969 the ZDF produced the two-parter The Irish Struggle for Freedom (director: Wolfgang Schleif with Karl Michael Vogler in the role of Éamon de Valera). Both here and in Neil Jordan's film Michael Collins in 1996 and the four-part series of the BBC entitled Rebel Heart from 2001 are even treated both the Easter Rising as the time of the Anglo-Irish War. While Michael Collins was apostrophized by some critics as an uncritical veneration of saints , the BBC series came under criticism from Northern Irish Unionists for allegedly unilateral support of the Republican standpoint. In 2016, RTÉ produced the five-episode series Rebellion, which is about the uprising.

See also

- Bloody Sunday (Ireland 1920)

- History of Northern Ireland

- Catholicism , Protestantism

- terrorism

- Bloody Friday

literature

- Max Caulfield: The Easter Rebellion, Dublin 1916. Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 1995, ISBN 0-7171-2293-X (English).

- Tim P. Coogan: 1916. The Easter Rising. Cassell, London 2001, ISBN 0-304-35902-5 (English).

- Michael Foy, Brian Barton: The Easter Rising. Sutton Publications, Stroud 2000, ISBN 0-7509-2616-3 (English).

- Peter de Rosa : Rebels of Faith. The Irish struggle for freedom 1916–1921. Droemer Knaur, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-426-77081-4 .

- Conor Kostick , Lorcan Collins: The Easter Rising. A Guide to Dublin in 1916. O'Brien Press, Dublin 2001, ISBN 0-86278-638-X (English).

- Dorothy MacCardle: The Irish Republic. A Documented Chronicle of the Anglo-Irish Conflict and the Partioning of Ireland. Wolfhound Press, Dublin 1999, ISBN 0-86327-712-8 (English).

- Fearghal McGarry: The Rising. Ireland. Easter 1916. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. a. 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-280186-9 .

- Francis X. Martin (Ed.): Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising. Dublin 1916. Methuen, London 1967 (English).

- Martin Prieschl: Ireland calls its children to the flag - The Easter Rising in Dublin 1916. In: Austrian military magazine . 45, No. 2, 2007, ISSN 0048-1440 , p. 173 ff.

- Charles Townshend: Easter 1916. The Irish Rebellion. Ivan R. Dee, Chicago IL 2006, ISBN 1-56663-704-X (English).

Web links

- Page from Irish historian Lorcan Collins about the 1916 Easter Rising with a tour of Dublin

Individual evidence

- ↑ Felix Kloke: Weaken from the inside - defeat from the outside. Uprising in enemy territory as an instrument of German warfare in the First World War. AVM, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-86924-166-1 .

- ↑ Herfried Münkler : The Great War. Die Welt 1914 to 1918. 2nd edition. Rowohlt, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-87134-720-7 , p. 555, urn : nbn: de: 101: 1-20140225337 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ^ I. Mallikarjuna Sharma: Easter Rebellion in India. The Chittagong Uprising (= Marxist Study Forum. Publication 16). Marxist Study Forum, Hyderabad 1993 (numerous sources in the appendices, including approx. 100 short biographies of freedom fighters).

- ^ Frederick C. Millett: The Easter Rising and Its Effect on Irish Literature and Music. (PDF; 38 kB) (No longer available online.) In: msu.edu. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007 ; accessed on July 6, 2018 .

- ↑ James MacKillop (Ed.): Contemporary Irish cinema. From the quiet man to dancing at Lughnasa. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse NY 1999, ISBN 0-8156-0568-4 , p. 237.

- ↑ Philip Johnston: Republican writes BBC's Irish drama. In: telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph , December 1, 2000, accessed July 21, 2017.