Miner figure

A miner's figure is a traditional Christmas decoration that is made today by the Erzgebirge handicrafts . As miners' candlesticks on altars, they are a regional specialty of liturgical candlesticks , which only developed in the Ore Mountains and the surrounding area.

history

Miner figures in churches

Altar candlesticks have been part of the furnishings in the churches of the Ore Mountains since the 13th century. The holders, mostly made of silver or bronze and often designed with tripods, remained part of the now Protestant churches even after the Reformation .

Miners and mining motifs also found their way into the furnishings of the Ore Mountains churches and religious rituals at an early stage. In the 15th century , miners from Freiberg carried candles during processions . The best-known example of the connection between church furnishings and mining in the Ore Mountains is the mountain altar , consecrated in 1521, in the Annaberg Annenkirche . The tulip pulpit in Freiberg Cathedral also shows a squire. In the Marienberg Church of St. Mary , to the left and right of the chancel, there are man-sized miner's figures made of wood. They are dated to the year 1687.

The original altar candlesticks were often the victims of marauding troops during the Thirty Years' War . After the end of the war, in the second half of the 17th century, large miners cast out of pewter prevailed as holders of altar candles. The town church in Zöblitz was a role model . Here, in 1672, three mining entrepreneurs from the mine uf der Weintraube in Pobershau donated two miner's candlesticks made in the Saigerhütte Grünthal . This initiated the spread. Examples of other pewter miner's chandeliers can be found as fittings in the churches in:

- Bockau (made in 1677, foundation of the climber Samuel Enderlein),

- Sosa (made 1678),

- Schellerhau (manufactured in 1685),

- Geising (manufactured in 1685),

- Crandorf .

Artisanal use

Craftsmanship also took place in the form of genre representation - as a cabinet piece for the court, a tribute gift - briefly for representational purposes. Ivory works and porcelain miner figures were also created for the same reason. Porcelain master Johann Joachim Kellers (1706–1775) created depictions of miners from porcelain around 1750, which are still preserved. This group of figures is reminiscent of the Saturnus Festival in 1719 near Dresden , where around 1500 miners marched in specially made uniforms and displayed lots of lights .

The candlesticks in the churches, some more than 60 centimeters high, had a representative effect on the churchgoers and were occasionally carved out of wood or later turned for private use since the end of the 18th century .

"The man-making is as old as the mountain cries" - popular saying

- Miner motif in the Erzgebirge arts and crafts for Christmas

Carved individual figures, today a symbol of the Erzgebirge Christmas art, have spread quite late. The first written mentions appear in the middle of the 19th century, e.g. B. writes EW Richter of "wooden risers" that were set up on Christmas Eve to the delight of the family. (1846, "Description of the Kingdom of Saxony")

There are only a few figures from this period, but as the product of naive folk art, these show a rather rigid form, a clear symmetrical structure, little wealth of detail. Arms and feet are often attached, sometimes also shaped as a sculptable mass. The costume was put on in the form of buttons and braids made of cardboard.

A pyramid from 1870 in the Schneeberger Museum of Mining Folk Art shows miners as light figures, representing the representatives of the various mining activities.

When carving associations were founded in numerous places in the Ore Mountains towards the end of the 19th century, numerous carved miners came into being as light-bearers. Figures from this period show z. Sometimes very detailed how the miners were dressed in their various activities and hierarchical levels such as mountain boy, mountain companion - servant -, housekeeper and steiger, where the necessary work equipment was attached to the clothing or was worn, and they show at least parts of how it works Has developed a professional or permanent habit.

The light is especially important for the development of the light miner - the light was indispensable for the work underground. First wood chips, tallow candles or oil lamps were used as pit lights , and later frog lamps; from the 18th century onwards the blind lantern ( cover ), which can also be found on many carvings.

From the light of the miners to today's custom of lighting windows

For the time around 1710, Karl-Ewald Fritzsch and Friedrich Sieber report on the importance of the light. The miners refused to have it provided by the mine owners. Otherwise the material used is unsuitable, "the shift supervisors buy old and stinking sleds and pull off the weight" . The miners preferred to buy the fuel for the pit light themselves, although in 1727 the Freiberg miners complained that wages had been the same for 60 years, and in 1724 they described their living conditions as follows:

- “We have to be satisfied when we with our wife and children can spare the dry bread, a so-called mountain chicken at the most, nothing other than a soup made from boiled water mixed with salt, in which a piece of oat bread can be cut. In this way our way of life is even more miserable and pitiful than that of a musketeer ... "

The mines worked three shifts. In the case of a dispute over working hours in 1709, these shift times applied: early shift 4 a.m. to 12 p.m., midday shift 12 p.m. to 8 p.m. and night shift 8 p.m. to 4 a.m. Saturdays were off work, but the miners still had to go to the Bergamtshaus every Saturday to collect their weekly wages.

In the Western Ore Mountains, mines and soaping plants were often far away from the miners' homes, for example in Eibenstock , Bockau and Sosa . They could therefore only be reached by walking there and back for hours and were extremely difficult in bad weather conditions, especially in winter. Therefore, there was also the practice that miners lived in the colliery houses all week and only went home on Saturdays, the non-working wage day. The working time model according to the Bergordnung für Eibenstock of March 15, 1534 took this into account:

- “Steiger and workers go to work in the forest on Mondays at 9 or 10 am. They work 4 hours on this day, 10 hours each on the other days. They go home on Saturday morning. "

In 1716 Christian Meltzer describes the Christmas mass on Christmas Day in the town of Schneeberg as follows:

"Before that time, however, sothane Christ-Metten was celebrated in such a way that the miners went to church with their burning pit lights, but kept these lights burning and well-stoked up on the upstairs church, just as the women people also put their lights in had their chairs […]. The vain youth, who loved all kinds of illumination, probably built up pyramids of lots of lights. Which then all causes that people from distant places and from the neighborhood have visited these Metten for their solemnity. "

In his Interesting Hikes through the Saxon Upper Ore Mountains, published in 1809, Christian Gottlob Wild describes his impressions from the surroundings of the Christmas mountain town of Schneeberg:

“But Christmas Eve itself, how illuminated it is celebrated. At that time I liked it very much in Schneeberg, where in the evening on the so-called mountains behind Neustädtel and on the Mühlenberge you can see almost all the houses brightly lit by the windows, which falls very nicely in the eyes in the dark of night.

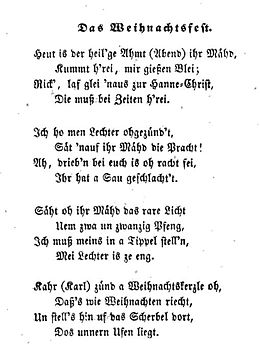

These reports show that Christmas was an outstanding festival in the life of miners. The light was of particular importance. This is understandable given the work in the mine in perpetual darkness. The darkness in the shaft was only faintly illuminated by the miner's glow. For most of the year, the miners came home in the dark for days, depending on their shift, or had to leave for work when it was dark. The longing for light should have been inherent in every miner. The described economic situation of the miners makes it appear doubtful that there was already a custom in the 18th and early 19th centuries to put lights in the windows during Advent and Christmas. The material for lighting was prohibitively expensive. How precious a light was in the first half of the 19th century becomes clear in the Holy Ombudsman (by Amalie von Elterlein , probably around 1830), the third stanza of which reads as follows:

"Sows, you mowing, the rare light / At twenty and twenty Pfeng, / I have to put mine in a Tippel, / Mei Lechter is ze tight."

Rare, so rare light, only one and only on Christmas Eve, this is what this stanza expresses.

Even in the second half of the 19th century, the majority of the inhabitants of the Ore Mountains lived extremely modestly. Alwin Gerisch describes his childhood in Morgenröthe-Rautenkranz around 1860/75 in Erzgebirge People - Memories : Very cramped living conditions with up to three families in a single room, there were no double windows,

"... in the persistent cold, the window panes were covered with a thick layer of ice for weeks and months, the window sashes swollen and frozen over."

Elderly people who were no longer able to work were admitted to the homes of families by the community for 14 days, thereby exacerbating the cramped living conditions.

"Rooms in which, because of overcrowding with people, as the saying goes, hardly an apple could touch the ground."

It is inconceivable that under the conditions described by Alwin Gerisch, which applied to over 90% of the population, an exercise practiced by a significant proportion of the population could develop, namely to put candles in the window.

The generally practiced custom of illuminating the windows in the Erzgebirge probably did not arise until the late 20th century when the Schwibbogen with electric lighting came on the market.

A development in the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1960s also contributed to the emergence of the practice of illuminating the windows in particular during the Christmas season: after the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, the Kuratorium Indivisible Germany developed the idea that the people of the Federal Republic should Should put a lighted candle in the window for Christmas to express their solidarity with their compatriots in the GDR. This was practiced almost everywhere - with a burning candle.

More than 200 years passed from the Mettenfeier in the 18th century, when the miners from the Ore Mountains brought their miners' lights with them, to today's custom. Today almost every window in the Ore Mountains is lit during Advent and Christmas. This practice is also widespread in many other regions of Germany, although significantly fewer windows are lit.

Different forms of light miners

In the past, the figures were usually provided with only one light and were therefore intended to be set up in pairs. But nowadays the Steiger only wears one light, because the mountain tick belongs in the right hand.

From the end of the 18th century, the number of symmetrical chandelier figures (that is, carrying lights on both sides) increased; some also had an arc or a yoke with lights (on their heads).

There are also carved figures that carry a pyramid in one hand (e.g. by Wilhelm Neukirchner, Zwönitz, 1890). The candles for operating the pyramid were in spouts on the base plate.

Angels and miners as Christmas figures

After the invention of inexpensive stearin (1818) and paraffin (1830) made it possible to design private Christmas candle celebrations in the 19th century , the production of turned and carved miners' figures as carriers of one or two candles in large numbers for private use prevailed. It was only at this time that the figure of the angel , who also carried lights , developed, for which there is no mining background. In his work Description of the Kingdom of Saxony , published in 1852, Ernst Wilhelm Richter describes Christmas rooms in the Kirchberg area and mentions:

"A miner (Steiger) or angel carved out of wood holds a crude, brightly painted (Christmas Eve) light in a spout."

The Christmas decoration together with the rotating chandelier after the "3rd or Hoh-New Year's Christmas Eve ”, that is, January 6th,“ canceled ”again, that is, put away until the next Christmas.

As a couple, miner and angel symbolize dual principles such as man and woman, as well as the worldly and the spiritual aspect of life.

See also

literature

- Karl-Ewald Fritzsch : Miners and angels as Christmas light bearers , in: Der Anschnitt 6 (1959), pp. 3–9.

- Karl-Ewald Fritsch: Bergmann and Engel , in: Sächsische Heimatblätter 9 (1960), pp. 534-542.

- Claus Leichsenring : On the history of the Erzgebirge miner's chandelier . In: Kulturbund Landesverband Sachsen eV (Ed.): Erzgebirgische Heimatblätter . No. 6/2014 . Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft Marienberg mbH, ISSN 0232-6078 , p. 2-8 .

- Claus Leichsenring: Early miner's chandelier made of wood. In: Calendar Sächsische Heimat. 2015.

- Siegfried Sieber : Miner figures made of tin and wood. In: Sächsische Heimatblätter . 9, 1958, pp. 558-564.

- Rudolf Königschmid: The miner's chandelier in the town church of Graupen . In: Nordwestböhmischer Gebirgsvereins-Verband (Hrsg.): Erzgebirgs-Zeitung. Monthly for folklore and local history of Northwest Bohemia . 5th and 6th issue of the 42nd year, (May – June). Teplitz-Schönau 1921, p. 49-51 ( digitized version ).

- Bernd Sparmann, Fritz Jürgen Obst : miner's chandelier - Saxon pewter in a special form. Husum, Verlag der Kunst 2015, ISBN 978-3-86530-200-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ulrich Lauf: The Saxon miners' union . In: Knappschaft (Hrsg.): Compass - magazine for social insurance in mining . No. 9 , 1987, pp. 6 ( revised version from 2011; PDF, 159 kB [accessed on January 22, 2015]).

- ↑ Bernd Sparmann, Fritz Jürgen Obst: The altar candlesticks of the town church to Zöblitz . In: Calendar Sächsische Heimat (= Wochenblatt December 9-15, 2013 ). 2013.

- ↑ Miner's chandelier in the Zöblitz town church

- ^ Bockau Evangelical Church

- ↑ M. George Körner: Old and new news from the mountain village of Bockau. Schneeberg 1756

- ↑ Evangelical Lutheran Church Sosa - equipment

- ↑ Schellerhau village church - photo of the two miner's chandeliers

- ^ Geising Protestant town church

- ↑ Lichterbergmann and Lichterengel in the Saxon Ore Mountains ISBN 3-88042-863-8 p. 6 ff.

- ↑ Günter Reinheckel: tin in crafts. In: Manfred Bachmann, Harald Marx, Eberhard Wächtler: Der Silberne Boden. Art and mining in Saxony. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt / Edition Leipzig, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1990, p. 362–374, here: p. 371 ff.

- ^ Karl-Ewald Fritzsch and Friedrich Sieber : Mining costumes of the 18th century in the Ore Mountains and in the Mansfeld region. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1957, p. 8.

- ^ A b Karl-Ewald Fritzsch and Friedrich Sieber : Mining costumes of the 18th century in the Ore Mountains and in the Mansfeld region. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1957, p. 7.

- ^ Karl-Ewald Fritzsch and Friedrich Sieber : Mining costumes of the 18th century in the Ore Mountains and in the Mansfeld region. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1957, p. 11.

- ^ Karl-Ewald Fritzsch and Friedrich Sieber : Mining costumes of the 18th century in the Ore Mountains and in the Mansfeld region. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1957, p. 4.

- ^ A b Siegfried Sieber: Colliery houses in the woodland around the Auersberg. In: Erzgebirge 1974. A yearbook for socialist local history. Stollberg 1973, p. 49.

- ↑ Celebration

- ^ Christian Meltzer: Historia Schneebergensis renovata - Schneebergische Stadt- und Berg-Chronic. 1716, p. 1177 Digital copy of the SLUB Dresden.

- ^ Christian Gottlob Wild: Interesting hikes through the Saxon Upper Ore Mountains. In Commission near Graz and Gerlach, Freyberg 1809, p. 145 digitized in the SLUB Dresden.

- ↑ Manfred Blechschmidt : The 156 stanzas of the well-known Erzgebirge Heiligobndliedes. 2nd Edition. Altis-Verlag, Friedrichsthal 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ In this notation by: Johann Traugott Lindner: Walks through the most interesting areas of the Saxon Upper Ore Mountains. Rudolph and Dieterici Verlag, Annaberg 1848, pp. 52–54 ( digitized in the Google book search).

- ^ Alwin Gerisch: Erzgebirgisches Volk. Vorwärts bookstore, Berlin 1918. Reprint 2008 by SPD local association Waldgebiet-Vogtland. ISBN 978-3-00-024279-3 , p. 13.

- ^ Alwin Gerisch: Erzgebirgisches Volk. Vorwärts bookstore, Berlin 1918. Reprint 2008 by SPD local association Waldgebiet-Vogtland. ISBN 978-3-00-024279-3 , p. 18.

- ^ Alwin Gerisch: Erzgebirgisches Volk. Vorwärts bookstore, Berlin 1918. Reprint 2008 by SPD local association Waldgebiet-Vogtland. ISBN 978-3-00-024279-3 , pp. 48-52.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education , accessed on February 8, 2015.

- ^ Karl-Ewald Fritsch: Bergmann and Engel. In: Sächsische Heimatblätter. 9, pp. 534-542 (1960).

- ↑ Ernst Wilhelm Richter : Description of the Kingdom of Saxony, Second Part containing the Zwickauer Directions District , JG Engelhardt-Verlag, Freiberg 1852, p. 488 digitized in the Dresden State and University Library

- ↑ Ernst Wilhelm Richter: Description of the Kingdom of Saxony, second part containing the Zwickau directions district , JG Engelhardt-Verlag, Freiberg 1852, p. 489 digitized in the Dresden State and University Library