Saigerhütte Grünthal

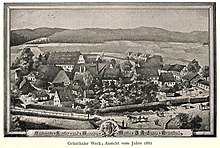

The Saigerhütte Grünthal is a historic ironworks about 2.5 kilometers southeast of the city center of Olbernhau in the Saxon Ore Mountains . Because of its closed and still largely preserved inventory of 22 functionally interconnected individual monuments , it is considered a globally unique ensemble monument for ore smelting in the Saiger process .

Originally built for smelting silver from black copper, the factory, which was initially founded by merchants in 1537, soon developed into the center of copper processing in the Electorate of Saxony . The Grünthaler roof copper , which was also used in many buildings far beyond the Saxon borders, achieved particular fame . In 1567 the Saxon state took over the hut. In 1873 the entrepreneur Adolph Lange bought it and ran the works under the name Sächsische Kupfer- und Messingwerke F. A. Lange in Kupferhammer-Grünthalfurther. After the Second World War, in 1947 the historical building stock was transferred to the newly founded Saxon Blechwalzwerke Olbernhau, later known as VEB Blechwalzwerk Olbernhau.

Between 1958 and 1960, it was redesigned into a technical display system. Today's museum complex is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Ore Mountains Mining Region .

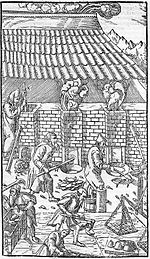

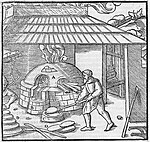

(= fusing of silver-containing black copper with lead and / or black lead )

(= heating the lead-copper-silver alloy to the melt at lower temperatures lead-silver alloy dripped out (saigerte), remained resistant copper-Erzkuchen)

(= "driving out" of the lead from the lead-silver melt)

(= annealing of copper)

(= removal of remaining alloy constituents for obtaining Garkupfer)

History 1537-1945

Founding and operation as a private steelworks 1537–1567

Founding by the Annaberg mountain master Hans Leonhardt

From 1530 to 1533, a certain Hans Leonhardt, as Bergmeister von Annaberg, was the top technical director of what was then the richest silver mining area in Saxony. Leonhardt must have had a considerable fortune, since he acted as chief surety for Heinrich von Elterlein , who had to provide a guarantee of 6000 guilders for his office as tithing of the sovereign . Von Elterlein was relieved of his office in 1533 on charges of poor management, and the guarantee became due. Leonhardt made his payment and in return had Elterlein, who owned the Saiger trade in the Annaberg mountain district, cede half of this trade. In the following years, both operated the Saiger trade, under which the smelting and trade in black and copper and lead was combined, and thus made a profit.

Leonhardt's motive for building a Saigerhütte was his participation in the Saiger trade and the great need for the smelting of silver-bearing copper ores from the Ore Mountains.

The increasing energy and material requirements of the Annaberg mining industry made charcoal and firewood more expensive and the water needed for stamping works and smelters was scarce . Leonhardt's choice of location for the Saigerhütte therefore fell on "a room above Olbernhau an Ilgen Grundigs purely to the Bemische grenntz ..." with sufficient usable water power and forest wealth, as the lending agreement of June 24, 1537 with the von Berbisdorfs attests. Although this resulted in greater expenses for the delivery of copper and lead, the abundance of wood outweighed this disadvantage. The smelter was put into operation in 1538 and in the first few years obtained its black copper from Schlema , Geyer , Annaberg, the nearby Katharinaberg , Freiberg and Ehrenfriedersdorf as well as from metal dealers in Breslau . Across the border, Leonhardt acquired three Hufen land with adjacent forest in 1538 from the landlord there, Sebastian von Weitmühl, in the triangle between Flöha and Natzschung .

Formation of a Saiger trading company

Although the construction costs of the smelter remained relatively low at 2061 guilders until the end of 1538, the advances for the delivery of copper and lead supplies exceeded Leonhardt's financial means. For the time being, among other things, Heinrich von Elterlein with 6000 guilders. At the autumn fair in Leipzig in 1538 , Leonhardt met a servant of the Nuremberg merchant Caspar Nitzold. The meeting was mediated by a certain Kilian Moler, whom Leonhardt had involved in his company. At the meeting, the partners agreed that Nitzold would participate in the Saiger trade in Grünthal with a larger sum. After this meeting, Moler traveled to Nuremberg to make further arrangements. Moler had a letter with Nitzold's suggestions about the manner in which he was involved secretly copied. He passed the copy to the Nuremberg businessman Conrad Weber, who got in touch with his brother-in-law Georg Österreicher from Augsburg . Österreicher decided to invest capital in Grünthal and for this purpose joined forces with the Augsburg metal wholesaler Matthias Manlich. Together with Conrad Weber and one of Manlich's servants, Austrians traveled to Grünthal and negotiated with Leonhardt about their own entry into the Saiger trade. In a conversation with Leonhardt, Weber succeeded in ousting Nitzold from the Saiger trade he was aiming for. After an inventory of December 18, 1538, there was a social contract between Leonhardt and Weber and his “co-relatives”, as the actual donors, Austrians and Manlich, were referred to anonymously in the contract text. The financial participation of wholesalers through intermediaries illustrates the efforts of the metal trade to gain influence over production in order to dominate the market and, if necessary, to monopolize it.

Efforts by the co-shareholders to expel Leonhardt

According to the partnership agreement, Leonhardt had to make a contribution of 15,000 guilders. Since he could not raise this amount on his own, he again borrowed a total of 5,000 guilders from Nuremberg merchants, including the Heurig brothers. The partnership agreement regulated the responsibilities of Leonhardt and Austrians: the former continued to manage the company, while the latter took care of the supply of black copper. Austrians were interested in expanding production and therefore tried to open up new delivery options in Austria and Hungary - until then, deliveries had only come from neighboring mountain areas in the Saxon and Bohemian Ore Mountains. However, it turned out that the company's capital was insufficient for further acquisitions of larger quantities from abroad. Austrians therefore suggested doubling the contribution on both sides in order to increase the capital of the Saigerhütte to 60,000 guilders. Leonhardt obtained the share he owed through further loans. At the same time, there were production difficulties due to the use of inferior raw materials, as well as inexperience of workers and a lack of skills in managing the smelting process. The official contract partner Conrad Weber used Leonhardt's increased absence during his raw material purchases as well as the complaints of the buyers of the cookware to press for Leonhardt's removal from the management of the Saiger trade and to claim the management himself. In order to avoid the accusation of having caused damage to the common trade, Leonhardt agreed to it. He was paid 1200 guilders to buy a house in Freiberg and to move there.

Trial for the exclusion of Leonhardt from the Saiger trade

The main blow against Leonhardt was carried out through accounting. Due to his limited experience in accounting matters, he had to rely on his employee Kilian Moler, which the co-partners in the background took advantage of. Leonhardt doubted the correctness of the first statement, which was presented in 1540. The third settlement, initiated in 1543, confirmed his doubts. Accordingly, he should have withdrawn or lost 9,526 guilders, 3 groschen. Leonhardt protested against this billing and demanded that all bills be checked from the start. After all attempts by Austria to persuade Leonhardt to give in had failed, he was granted an objection period until the Leipzig Easter Fair in 1544, but he could not argue against the accounting tricks of his partners. While Leonhardt was traveling, Austrians, Weber and, as a representative of Manlich, Silvester Rodt met at the Easter fair in Leipzig. Since Leonhardt had not appeared, they declared him fugitive and stated that he owed them over 20,000 guilders. With this demand, they had the Saigerhütte and all its supplies confiscated.

As a result of a 1544 trial about the disguised mismanagement of the plant, the arbitration tribunal that met in Freiberg reached a compromise: Leonhardt was to be excluded from the Saiger trade, he had to surrender all copper, silver, trading books and bonds. His house in Freiberg was confiscated. In return, Austrians were supposed to pay out 10,000 guilders to Leonhardt, with which he had to settle all debts - Leonhardt was practically bankrupt.

Leonhardt appealed against this judgment, but only managed to get Duke Moritz assigned an accountant who began checking the accounts. This was able to prove that the accounting of 1539/40 was wrong - instead of a loss, a profit was stated. A second audit of February 4, 1546, which also included the other accounts, came to similar results. Based on this, Leonhardt succeeded in resuming the proceedings in Leipzig. Due to the siege of Leipzig in the course of the Schmalkaldic War , the proceedings in Freiberg had to be continued from January 1547. On March 11, 1547 the judgment was passed. In this, the final invoice, which the Austrians had arranged at the end of 1543, was confirmed with a correction of 968 guilders at the latter's expense. The assets of the Saiger trade were determined to be 10,978 guilders, 6 pfennigs and should be divided between both parties after the settlement. However, Leonhardt's legal costs far exceeded the compensation. With the confirmation of the judgment by the supreme court lord, Duke Moritz, on March 20, 1547, no further legal remedies arose against this judgment.

Leonhardt tried, however, to continue to challenge what he believed to be an unjust judgment. Because of this, he was arrested on October 13, 1547 for resisting the ruler's ruling. He was released on bail. With the loss of the Saiger trade, through which Leonhardt had lost a large part of his fortune, another process began. In this, the Heurig brothers from Nuremberg demanded money back from Leonhardt. In the course of this process Leonhardt probably died in November 1548, because on December 7, 1548 the electoral chancellery caused the council of the city of Freiberg to release his assets for his heirs and creditors.

Acquisition by the Uthmann family

Christoph Uthmann acquired the facilities around 1550 . He successfully invested his fortune in various mines and thus became one of the financially strongest mining entrepreneurs in Annaberg. He had the Elector August issue him a privilege , according to which silver-containing copper had to be delivered to him from all copper mines in the country at a fixed price - this was a good basis for business and all competition was ruled out. Uthmann died in 1553 at the age of 46. His legacy was the 39-year-old widow Barbara and her twelve children, of whom Lucas, Paul, Jacob, Heinrich and Hans dedicated themselves to the Saiger trade. Daughter Barbara married the Dresden mint master Hans Bienert in 1555. It is not known whether Barbara Uthmann took care of the business herself or whether her sons Heinrich and Paul, possibly also her son-in-law Hans Bienert, took over the management.

On February 19, 1554, Barbara Uthmann and her children obtained from the von Berbisdorfs the fiefdom of the property in fiefdom from Hans Leonhardt. Even Sebastian of Weitmühl confirmed the deed of gift for the Czech territory. On July 24, 1554, the elector left her to buy copper for only one year, which, however, did not provide any security for a planned management. On August 22, 1555, at Uthmann's insistence, the elector promised an extension of three years, but with the restriction that the price was now based on the silver content. The elector regulated the price of silver and copper through annual rescripts . After this period had expired, the elector had the serious intention of taking back the copper purchase - the smelting of the metals was a lucrative business. Uthmann, on the other hand, achieved with petitions and plausible justifications that on August 1, 1559, she was given the copper monopoly for eight years, since she and her husband had promoted mining "for the common good". The elector tied the further transfer of the monopoly to the annual payment of 5000 guilders to the electoral silver chamber.

In the 1560s there was a lot of construction activity in the steelworks, the most important buildings of which were erected during this period. Under the leadership of the Uthmanns, the area with the most important buildings was provided with a wooden enclosure, which later gave way to wooden palisades. The Lange Hütte was rebuilt in 1562 as a central production site, whereupon among other things. the year 1562 indicated in the sandstone portal on the gable side. This shows that the previous building from 1537 must have been worn out. Another new building was the cooking house , with which the refining processes , ie the cooking and drying of the copper, could be outsourced from the Lange Hütte. This started to distribute the entire production process to different buildings. Furthermore, they had the new house built , which later became the trading post and the mansion in which the family lived.

Existence and operation as a state ironworks 1567–1873

Acquisition by the Electorate of Saxony

Repeated complaints from mine owners to the elector about the copper monopoly of the Saigerhütte met the economic interests of the sovereign, who did not extend the Uthmanns' privilege of 1559 despite their request. They were therefore forced to offer the facilities to the elector for sale, and on August 6, 1567, the purchase contract was concluded.

According to the historian Hanns-Heinz Kasper , of the required 13,665 guilders, using his position of power, the elector only paid 8,000 guilders for the facilities and 1,680 guilders, 16 groschen and 11 pfennigs for the metal stocks. The local researcher Bernd Lahl , referring to the original purchase letter, names a different purchase price of 13,239 guilders, 5 groschen and 5 pfennigs for systems and stocks.

With the purchase, the electorate, as the smelter, secured the significant income from silver mining through the Saiger process for the state treasury.

Electoral administrative structures

Now in state ownership, the iron and steel works were affiliated to the Annaberg Mining Authority and later directly subordinated to the Upper Mining Authority. A request made by the miners of the ironworkers for the preservation of the working and living conditions granted by the Uthmann family became the basis of the first electoral work order. The management of the hut was entrusted to a factor, the top supervision was given in the first two decades of the tenth of the mining authority Annaberg.

According to the electoral work order, the hut factor had to take care of the administrative, economic and production areas in particular. Every month he had to prepare a situation report, to keep buildings in structural condition, to assign servants to rooms and chambers and also to make sure that they maintained these and their inventory at their own expense. He continued to take care of the bookkeeping, for which he could hire a clerk or accountant at his own expense. The bookkeeping related to money movements as well as the development of stocks and inventories. He instructed the payment of wages, materials, transport and storage of supplies. In his supervisory role, he was only allowed to leave the plant for a longer period with the approval of the mining authorities. Furthermore, his technical knowledge of production was required. This included trying the ores and metals and determining the additions and quantities for the smelting processes. He had to organize the purchase of the black copper in the individual mountain areas and the transport to Grünthal - this also applied to lead from Freiberg. The metals were to be kept safe and stocks of wood, coal, ash, etc. To create resources in order to achieve the most continuous production possible. In the first few years, molten cooked copper and silver had to be delivered to the tenth in Annaberg, or to be sent to specified recipients.

The social position of the hut factor in the territory of the Saigerhütte and in the mountain state was far higher than the work order states. The privileges granted to the previously private owners passed to him. He was the judge of all residents and visitors to the territory, and he was also entitled to patronage over the church and school. He was the representative of the authorities for both the work and the municipality. The position in the Saxon state was comparable to that of the miner , even if the first factor was still subordinate to the Annaberg Mining Authority. The reward for the factor also corresponded to that of a mountain master. His life was very different from the inhabitants of the territory. Although he lived in the center of the factory, the factory, in terms of standard of living he was able to keep up with the nobility.

Interim shutdown and recommissioning

One focus of the government activity of the new Elector August von Sachsen was an active economic policy. He devoted the greatest attention to mining and metallurgy, which he saw as important foundations for the political power of the Wettin ruling house.

The elector had a personal preference for metallurgical and manual work. When he took office, he had a smelting house built for demonstration purposes of new technologies in order to spread them in the country if necessary. He expected a higher yield and a decrease in the use of raw materials, which should ultimately improve government revenues. By order of the Elector, the Neue Hütte (a Saigerhütte) was built on the Weißeritz near Dresden in 1583 . It was decided to shut down the Saigerhütte Grünthal, the workers should continue to be employed at the new location, the factor Paul Uthmann, who was appointed to Grünthal in 1579, took over the management of the new hut. After the death of his father, the son and new elector Christian I revised this decision - he did not like the annoyance associated with the ironworks. He commissioned the bailiff of Lauterstein, Hans Heintze, with the examination of the reopening of the Grünthaler Saigerhütte. Heintze's suggestions in this regard were accepted and in 1586 he was appointed to the factor of the hut. The new beginning was connected with extensive reconstruction work of the facilities with partial conversions and new constructions. Production started again from 1587. The Dresden stocks of black copper were transferred to Grünthal and processed.

The regulations issued to maintain the monopoly are important, such as the Grünthal Saigerhüttenordnung of February 8, 1612, the Grünthal Saigerhütten-ore purchase patent of June 3, 1619 as well as other regulations “against troublemakers and domestic traders with copper traveling around in the country”, e.g. B. the patents of January 26, 1613 and August 10, 1611.

During the Thirty Years War

The first years of the war did not result in any direct damage to the facilities, but had an impact on production and the situation of the ironworkers. The general economic decline at the beginning of the 17th century had also affected Electoral Saxony. Silver imports from overseas had a heavy influence on Saxon ore mining; in addition, the abundant deposits in the mining towns had been used up. While in 1568/78 the Saxon mountain districts still supplied around 40 percent of the Saigerhütte's black copper requirements, this proportion fell to just 9 percent by 1618. In 1626, the Saxon mining industry no longer even delivered 35 quintals (around 1799 kg) to Grünthal.

In 1610, the elector had proclaimed a privilege that allowed and promoted the further processing of slag that had been dumped without taxes. The hut factor at the time, Michael Rothe, recognized the advantages for the Saigerhütte and ensured that the hut was granted this privilege in 1619.

During the tipper and wipper era , the Grünthal mint was set up in the Althammer in 1621 as a branch of the Dresden mint . After the end of the tipper time and the return to imperial coinage was made in 1623 to close the Kippermünzstätte . The processing of canceled coins brought the smelter, and thus the elector, a high profit. The Saigerhüttenknappschaft commissioned a trophy in 1625 , which was made for the high sum of 104 thalers.

After the death of his father in 1623 August Rothe took over the position of the factor. He tried to obtain the privilege of erecting a wire works on the Natzschung from the Elector , which he finally succeeded in on June 26, 1626. The Rothenthal refugee settlement developed around this wire hut .

The war situation worsened in 1632. By order of the elector, every tenth man was mobilized from the neighboring offices, manors and towns and ordered to guard the hut and the border immediately behind it. However, the conscripts showed little willingness for military service - some contingents did not appear at all, others left the position due to a lack of food and pay. At the beginning of September General Heinrich von Holk reached the Saigerhütte with 5500 men and took it without resistance. The workers had fled into the woods, and the factor and his family had come to safety in Freiberg. The workers could not return until the end of November. In 1643, Swedish troops had again occupied large parts of Saxony and the Saigerhütte was extorted several times for protection money. On January 3, 1646, 300 Swedish horsemen coming from Bohemia attacked the Saiger hut. On January 5, 1646, another 500 Swedish riders came. They looted here and in Olbernhau for twelve days, burning down the gatehouse, schoolhouse and room house. After the troops had withdrawn, the Rothe factor returned to Grünthal and set about putting the hut back into operation as soon as possible. He also got through that wooden palisades were built to protect against further attacks. No further damage was reported until the peace treaty in 1648.

After the Thirty Years War

The raids by Swedish troops had badly damaged the facilities. The buildings were restored with the reconstruction of the gatehouse, school and room house in 1651, but there was a shortage of skilled workers; it was not until 1654 that there was again a demand for cookware. With the exception of the Freiberg mining area, ore mining in the Ore Mountains did not recover after the end of the war. An attempt was made to create incentives for reopening the pits with special concessions. These discounts also related to the Saigerhütte in order to utilize its production capacities. However, the request mostly did not succeed. A stone curtain wall with gates was built in 1656 to fortify and protect the residents and facilities .

In 1651 the hammer mills only achieved a capacity utilization of 60 percent. In 1656, the Saigerhütte applied to the Elector to close other copper hammers in the country in order to improve profitability. The three hammer mills had a total capacity of 21 quintals (around 1079 kg) of cookware per week. The hammer in Wilkau was prohibited from processing copper in 1665, in the same year the state bought the hammer in Dresden in front of the Wilsdruffer Tor and handed it over to the administration of the Saigerhütte.

A significant change occurred in 1669 in the purchasing of black copper. After the end of the war, almost exclusively black copper from the Freiberg mining area was processed, and extensive deliveries from the Mansfeld region were now taken over. In some cases, these accounted for up to 40 percent of the quantity delivered.

In the period from 1648 to 1693, production continuity was restored, but full utilization of the facilities remained unmatched.

Existence and operation until 1763

When Elector August the Strong took over government in 1694, the policy of the Electorate changed fundamentally. In this phase, in 1701, a private lease of the Saigerhütte was considered. The chief miner Abraham von Schönberg intervened in the relevant negotiations . In a detailed report, he came to the conclusion that the proposed lease was ultimately disadvantageous for the state. The elector loses the right to influence production and price policy. The damage to the mining industry is considerable and destroys traditional shelf rights. The lessee's profits, on the other hand, are high and escape the state. In 1710, the elector had the state smelting works grouped together in the general smelting administration - Grünthal and the state blue paint works remained unaffected by this. The main supplier for black copper and lead was henceforth the general smelter administration. On the one hand, the state orders ensured a continuous supply of raw materials, on the other hand, prices were dictated and the selling prices for deliveries to state institutions were sometimes below cost , which impaired profitability.

In July 1710, the son of the Russian tsar, Alexei , traveled to Karlsbad in preparation for his father's cure . He visited the Grünthal plant on July 10th to observe the Saiger process for silver separation from copper ores. a During the two Silesian Wars , the Saigerhütte remained free of war damage, but the billeting of Saxon troops at the beginning of 1741 as well as forays by Hungarian hussars and Pandours resulted in burdens. In 1741 the smelter was instructed to strike tombac in order to mint coins to pay for Saxon regiments in Poland. These were given the designation Grenadier coins . The Grünthal mint also revived during this period and a second minting period began.

During the Seven Years' War , the facilities were idle because the Prussian occupying forces significantly impeded the transport of materials and only made exceptions when they needed it. During an attack by the Prussian military in February 1757, the plant and metal supplies remained untouched. A year later, however, on February 7, 1758, Austrian hussars and Croats transported 293 hundredweight of copper to Prague . After the end of the war, the requisition was compensated with 3,203 thalers.

The factor Carl Friedrich Rothe left the Saigerhütte in 1741 after a dispute with the senior mining authority, which ended the more than 120-year-old management and administration tradition of this family. The elector pursued a different policy towards the state and private hammer mills. The outstanding position of Grünthal in the non-ferrous metallurgy sector should be preserved and furthermore expanded. In the years 1729/30 work had to be done in the hammers from 2 a.m. to 6 p.m. in order to process the orders. As a result, the Großhammer was built below the Saigerhütte on a site on the right-hand side of the Flöha in 1732 . The Kupferhammer on the Weißeritz, leased from the Saigerhütte, was sold in 1700. In addition to purchasing Grünthaler Garkupfers, he was allowed to accept and process scrap copper from coppersmiths. In addition to this, a copper hammer worked at Bautzen from 1755 , and another worked in Neustadt an der Orla from 1776 . As early as 1713, Christian Mäder received a concession to build a hammer mill in Brüderwiese . However, he was forbidden to use copper in his new hammer. His further application to build a new copper hammer on the Schweinitz was rejected by the state authorities in 1717.

For the period from 1694 to 1763, a strengthening of the position of the Saigerhütte within Saxony can be seen, which related in particular to the development of the manufacturing sector. In contrast, the extraction of silver and baked copper declined in the same period, but the income from copper extraction and processing increased, which was ultimately based on price increases. The economic importance for the Saxon state budget decreased. Around the middle of the century, Grünthal was one of the leading companies in copper metallurgy. This is also reflected in the most important publications on metallurgy at the time, which cite examples from Grünthal.

Economic crisis after 1763

A serious crisis began from 1764/65. Coppersmiths in Leipzig and Zwickau bought their copper in Saalfeld , Graefenthal and Schönberg because of the lower prices . The mill management then lowered prices by 12.5 percent and at the same time considered increasing the number of copper hammers in order to broaden the range. However, the sales opportunities were too uncertain and the buildings were not built. An attempt was made to counteract the decline with personnel changes. Head of the hut, Mätzel from Freiberg, was employed as a factor and Friedrich August Boese from Hettstedt was won over as the clerk, who took many initiatives to improve the Saiger work according to Mansfeld's findings and to improve the existing Saiger, drying, cooking and driving ovens. Severe floods of 1771 intensified the decline: on June 3 and 4 and then on June 22, 23 and 28, 1771, the worst damage in the plant's history occurred, after the plants had already been in operation in 1723, 1748 and 1750 Had been affected. Both rivers overflowed their banks after several days of rain. The water dammed up man-high in the hammers. The flea bridge was partially torn away. The repair of the damage caused took several years and cost around 900 thalers.

In 1774, copper sales came to a complete standstill. Officials and blacksmiths were sent on business trips to investigate production and prices in other hammer mills and to pay attention to new production processes. In this situation, the Oberbergamt therefore suggested in 1777 that the Saichtung in Grünthal be stopped and relocated to Freiberg. With detailed proposed solutions for continued operation, the factor at the time succeeded in circumventing this variant.

The plant suffered severe damage during the War of the Bavarian Succession . On September 20, 1778, Austrian troops advanced after a battle near Marienberg via Rübenau to the Saigerhütte, occupied it with 300 men, demanded money and the delivery of the metal supplies. Both had been brought to safety beforehand, which is why the occupiers demolished ovens and started fires in several places. After an hour, the Austrians withdrew and the fire fighting began. It took years for the plant to recover somewhat from the war damage.

With the construction of the first amalgamation plant in Halsbrücke in 1790, a considerable part of the ores containing silver went there through the general smelting administration. However, the Saiger process remained the basis of the melting process, although other processes were already more productive at the time.

In the 19th century

By 1802 the Zaine for the production of copper coins for the Electorate of Saxony had been delivered from Grünthal to Dresden. The considerable transport costs meant not only rolling the copper plates in the Saigerhütte, but also the minting itself. Very good results in the trial minting resulted in the entire copper minting of the Dresden mint being relocated to Grünthal in 1804. The Grünthal pfennig coin had to cease operations in 1825 for technical reasons.

After the defeat of Prussia in the double battle at Jena and Auerstedt , Saxony took the side of the Rhine Confederation , which the conqueror honored with the dignity of Saxony's ruler. From 1807, the plant was therefore called the Royal Saxon Saigerhütte . Favored by the continental block imposed by Napoleon Bonaparte , the import of English competing products was prevented, which allowed the mining production of Saxony to increase; The Saigerhütte also benefited from it.

Since around 1800 the raw material copper had lost importance compared to the growing use of iron. Grünthal worked continuously to improve the technologies, but the basic process of melting out metals through different temperature levels remained identical. Further processing in the hammers also remained unchanged for a long time. With the brass works Niederauerbach the first rolling mill was built in Saxony in 1817. After a copper rolling mill went into operation in Rothenburg, the construction of a rolling mill was discussed in 1818. At the same time, the relocation of the Saigern to Muldenhütten was considered. The cost analysis showed no advantage in the result. The Saiger process was not relocated and the rolling mill - for an estimated cost of 12,000 Reichstaler - was not built.

The transition to the decimal system in 1843 and the gradual harmonization of weights and measures affected the economy. From 1841 the Reichstaler became the single currency.

From 1839 the project of a rolling mill was pursued again, the machine director Christian Friedrich Brendel pushed it forward in 1841. After two days of on-site consultation, the decision was made on July 13, 1846 for a rolling mill, which was completed in 1850. It is noteworthy that the Saigerhütte was able to finance the new building from its own resources.

Saigern in Grünthal was discontinued around 1846/47 - the processing of silver-containing black copper had been declining for decades, and Muldenhütten took over the processing using the extraction process . Other smelting actions, such as the smelting of slag for the production of nickel food , allowed smelter-like production until around 1856.

From 1848 the plant was called the Royal Saxon Copper Hammer Grünthal . Due to financial difficulties of the general smelting administration, the Saigern in Grünthal was briefly resumed in 1850. In order to get the means of payment again, larger stocks of material had to be processed quickly, which the shutdown facilities in Grünthal were able to do. In a year and a half, the stocks were smelted, albeit at a loss. In the first quarter of 1853 the last saigert was made in Grünthal. As a substitute for Saigern, copper refining was developed from 1853 onwards. The cooking house was converted for this purpose and equipped with a refining oven.

Good operating results of the rolling mill and increased demand towards the middle of the century led to considerations in 1855 to build a second rolling mill. The new rolling mill was handed over on July 20, 1859; the equipment was supplied by the Richard Hartmann machine factory from Chemnitz. With the necessary construction work, the costs amounted to 37,140 Reichstaler; once again the hut was able to bear the costs itself. With the introduction of rolling mill technology, an average of 7422 quintals (= 371.1 t) of raw material was processed per year - seven times the performance of the hammers.

The new rolling technology and copper refining made it possible to expand the range. Measured in terms of production, the Grünthal plant gained a share of more than five percent in Germany's copper processing industry. The period of transition from hammer to rolling mill technology was accompanied by extensive structural changes, whereby the focus was not on new construction, but on renovations and extensions. In addition to other buildings, this affected the central Saigerhütte, the cooking house, the greenhouse and the individual hammers.

As early as 1862, the growing demand and an increasing number of orders gave rise to the idea of a third rolling mill. The calculations for the planned new building were available in 1864, and art master Schwamkrug was commissioned with detailed calculations. However, in view of the privatization considerations, the project was postponed from 1864.

On March 5, 1870, the Saxon state parliament decided to sell the steelworks. The decision was based on the view of the MPs that the state should renounce its commercial enterprises: “Because not only that it does not appear economically justified for the state to carry out such industrial enterprises on its own account, it is also financially advisable to do so Approve sale. ”- On June 14, 1871, the Landtag Oberbergrat commissioned Maximilian Edler von Planitz with the sales negotiations.

Sale of the work to Franz Adolph Lange in 1873

Existence and operation until 1918

Three interested parties responded to the tender by the Ministry of Finance. The entrepreneur Franz Adolph Lange , who works in Aue , was auctioned off on January 14, 1873, for 135,000 thalers . At the same time he committed himself to preserving and cultivating the existing tradition of the work. Dated April 1, 1873, the Royal Saxon Hammer Administration announced that the work was transferred to Lange with effect from this date, and from then on it was known as the Saxon Copper and Brass Works F. A. Lange in Kupferhammer-Grünthal .

Lange used the time of the start-up crisis that began in autumn 1873 to invest in the renewal of machines and systems as well as the introduction of steam power as an energy supplier. He also bought several pieces of land in order to be able to gradually expand the plant. An important factor for the further development and expansion of the plant was the opening of the Pockau – Olbernhau railway line in 1875 and, in particular, the opening of the nearby Grünthal station with the continuation of the line to Neuhausen in 1895. This enabled the procurement of raw materials and shipping of products facilitated and accelerated. The number of employees rose from the beginning of 60 to 190 in 1883. At the beginning of the 1880s, the Great Depression followed the start-up crisis. Once again, Lange used the location to expand his company by purchasing the former Schweinitzmühle ( ⊙ ) in Böhmisch Grünthal in 1883 and setting up a rolling mill and wire drawing shop here.

In 1895, the expansion of the Grünthal plant was largely completed; the number of employees, including those in Böhmisch Grünthal, was around 800, and sales in 1884 amounted to 1.45 million marks (today around 11,000,000 euros). In 1907, a three-kilometer aerial cableway to the Grünthal train station was built to transport anthracite coal from Böhmisch Grünthal, and the plant also obtained the fuel for its production processes. Franz Adolph Lange retired from the company in 1885 and left it to his son Gustav Albert Lange .

When many workers were called up for military service in World War I , the number of employees fell to less than 500, and civil production was almost ceased. Difficulties caused inter alia. the supply of food to the workforce. After the end of the war, the company management took stock of the development since the takeover by the Saxon state and came to the conclusion that research and development had been neglected compared to the economic results. Compared to its competitors, the hut had fallen behind in this regard.

Existence and operation after the First World War until 1931

There were significant changes near the border: Czechoslovakia had emerged as a new neighboring state. The plant there was converted into F. A. Lange GmbH Grünthal and a branch was set up in Prague. After the end of the war, the company's investments initially concentrated on the rolling mills and their electrification.

With the onset of the upswing after the inflation of 1923 , several building projects were started. Rolling mill I from 1849 was completely renewed, and new rolling mills, annealing furnaces and generators were procured. A turbine house and a transformer station were built on Neuhammer from 1925 to 1928. In 1926 a locksmith's shop was added, which was expanded again in 1928. The hammer frame as well as the forge equipment remained in place; however, this area of the building was only used as a repair shop. The global economic crisis put an abrupt end to the renovation measures. Between 1919 and 1931 the number of employees decreased to 188, in 1924 it was 965.

Various measures to reduce costs, such as the administrative amalgamation with the plant in Auerhammer and the approval of a loan by the city of Olbernhau, did not stop the economic decline. After both factories lost millions for the 1930 financial year, the Saxon Ministry of Economic Affairs reached an agreement to liquidate both factories and convert them into a stock corporation. On July 2, 1931, the F. A. Lange Metallwerke AG Aue was founded in Leipzig , which included both plants in Auerhammer and Grünthal.

Existence and operation within the stock corporation

From 1933 onwards, the economic situation of the plant improved again with the appointment of a new operations director and armaments contracts . However, during the global economic crisis, investments in the renovation of buildings as well as the machinery and equipment were neglected, which had a negative effect on the now increasing production. The buildings in the complex around the former Saigerhütte were particularly affected. The problems were aggravated by the destruction of a strong flood on January 3rd and 4th, 1932: The old hammer was devastated, a workers' house was partially torn away by ice drift. In 1937 the Grünthal plant had 32 employees, 287 workers and 19 apprentices. 14 roll stands, eight flame furnaces, two drop hammers , a steam engine, six turbines and 110 electric motors were used.

In 1936 negotiations were held for the sale of the Schweinitzmühle located on Czechoslovakian territory . As a result, operations went to the Czechoslovak Arms Factory AG based in Brno on January 1, 1938 . After the Munich Agreement of October 29, 1938, the ČSR had to cede significant parts of the area, which in turn affected the conditions of the Schweinitzmühle. After a temporary standstill, production was resumed there on October 5, 1938 with 138 employees.

Second World War, dismantling and transfer to public property

With the transition to the war economy, the manufacture of consumer goods gradually faded into the background. In 1942, two new strip rolling mills went into operation. From 1943 to 1945 investments were made in machines and systems despite the war . Linked to this were expected increases in sales of RM 4.5 million . The workforce increased from 231 to 307, in the Schweinitzmühle from 176 in 1942 to 266 the following year.

The city of Olbernhau, the factories in Grünthal and the Schweinitzmühle were spared from bomb damage. On May 8, 1945, the Soviet Army moved into Olbernhau. In accordance with the provisions of the Allied Control Council , the plants of F. A. Lange Metallwerke AG were placed under sequestration and then dismantled. The plant in Schweinitzmühle - now again on Czechoslovakian territory - was liquidated.

The history of metallurgy at the Grünthal site, which had been going on since 1537, did not end there. In 1947, the Sächsische Blechwalzwerke Olbernhau , later VEB Blechwalzwerk Olbernhau , was founded with the existing facilities .

Products, sales and key figures 1537–1945

General trend development

Originally built for smelting silver from black copper, the plant later developed into the center of copper processing in the Electorate of Saxony . From the second half of the 18th century, the production profile shifted primarily to processing copper into intermediate and finished products.

Products and key figures

No production figures are known until 1568. From 1568 to 1578, 35,872 marks (approx. 8398 kg) silver were extracted from black copper; In the period from 1566 to 1578 the company produced 18,039 ct. (approx. 927 t) of cookware. For the period from 1586 - recommissioning after temporary shutdown - the invoice books received provide precise information on production.

Silver production declined at the beginning of the 17th century and fell enormously during the Thirty Years' War. In addition to the extraction of black copper, scrap copper from the country's coppersmiths, who are obliged to deliver, was also used to produce cooked copper. With the beginning of these inputs, copper scrap became increasingly important for production. Garkupfer was delivered as grained, cast or forged copper as well as in the form of sheets and plates. The increase in production capacities for hammered sheet metal resulted in a proportional increase from around a third in 1579 to almost the entire amount of copper sold in the 17th century.

After the end of the Thirty Years War, old coins that were melted down here were another important raw material. Polish shillings were bought up from 1668, and from 1681 Spanish copper coins that had been brokered via England were also processed. From 1659, the factory supplied copper wire in the form of rings. The consumption of copper goods was encouraged by the sovereign forbidding the iron hammers to make furnace pots and boxes out of iron. This was reserved for the coppersmiths.

In the period from 1648 to 1789, a total of 208,663 marks (approx. 48,848 kg) of silver were extracted and 117,210 ct. (Approx. 6024 t) of cooked copper were produced. As a result of the Seven Years' War , inferior coins issued during wartime were melted down again, which is why higher amounts of silver appear in the books after 1763. If these smelting campaigns were neglected, the amount of silver produced tended to decline and after 1784 it sank to less than 1000 marks (approx. 234 kg) per year. The invoices show the use of cooked copper produced in Grünthal, among other things. as cooking utensils, bells, cannons, copper for casting purposes, granular copper for the coins and roofing sheets. Sales to state institutions played a significant role for the plant. The recipients here were the coins, the stuff and casting house and the court smithy. In addition, at the beginning of the 17th century, the hut benefited from the construction of numerous new buildings in the Electorate, which were given a roof made of Grünthal roof copper .

| year | 1828 | 1829 | 1830 | 1831 | 1832 | 1833 | 1834 | 1835 | 1836 | 1837 | 1838 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black copper delivered | 32,805.27 | 33,372.33 | 39,014 | 38,225.84 | 46,293.68 | 32,407.56 | 29,614.64 | 47,364.15 | 37,427.63 | 33,373.03 | 43,844.15 |

| Black copper fails 1 | 27,848.04 | 28,329.84 | 32,698.16 | 42,282.77 | 63,552.63 | 63,719.58 | 28,638.19 | 27,777.38 | 31,940.13 | 34,278.46 | 39,777.41 |

| Fine silver brought out | 117.51 | 115.7 | 158.99 | 177.88 | 271.32 | 140.36 | 78.19 | 127.65 | 130 | 129.29 | 143.49 |

| Cook copper applied | 22,782.77 | 26,031.22 | 25,875.64 | 27,288.45 | 26,878.02 | 34,624.43 | 26,357.79 | 20,950.42 | 27,582.55 | 27,165.23 | 27,277 |

|

1 Versaigerte amount of delivered and available black copper

|

|||||||||||

The Grünthal roof copper was a special product of the plant, some of which can still be found across Europe today. Over 400 structures bear or carried a copper roof skin that was hammered or rolled in the Grünthal hammer and later rolling mills. Emphasize in this respect are religious buildings such as the Frauenkirche , the St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, as well as secular buildings such as the Reichstag Building and Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Reich courthouse and New Town Hall in Leipzig, the town halls of Hamburg and Hanover and locks in Charlottenburg , Dresden and Vienna .

In the period from 1790 to 1830, 16,875 ct. (Approx. 867 t) of cooked copper were produced from black copper and 33,623 ct. (Approx. 1728 t) from copper scrap, and 133,963 marks (approx. 31,361 kg) of silver were extracted. The significant increase in the amount of silver compared to the end of the previous observation period results from recurring smelting campaigns. Copper was increasingly produced from the processing of secondary raw materials. Based on this development, the technical modification and expansion of the plants shifted to the further processing of copper and an improvement of the techniques for secondary production. These were, for example, the smelting of nickel-containing slag and refining processes for raw and slag copper.

| year | 1841 | 1842 | 1843 | 1844 | 1845 | 1846 | 1847 | 1848 | 1849 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivered copper | 63,021.5 | 63,646 | 54,173.75 | 43,696.25 | 38.904 | 41,342.5 | 41,617.81 | 41,499.06 | 64,455.13 |

| Copper processed 1 | 63,925 | 60,668.19 | 56,885.5 | 40,437.5 | 39,336 | 44,447.75 | 42,724 | 40,769.75 | 57,614.56 |

| Copper goods made | 62,784.5 | 59,586.5 | 54,671 | 39,716 | 38,843 | 43,298.75 | 41,365.75 | 39,534 | 56,588 |

| Copper goods sold | 62,887.5 | 55,469.5 | 43,668 | 37,708 | 42,252.5 | 43,654.5 | 45,312 | 37,488.5 | 56,956.06 |

|

1 Processed quantity of delivered and in-stock copper

|

|||||||||

From the mid-1850s onwards, in addition to the non-ferrous metals that had prevailed until then, iron was also used as a material, which was used to supply almost all machine factories in Germany, especially the aspiring locomotive builders .

| year | 1850 | 1851 | 1852 | 1853 | 1854 | 1855 | 1856 | 1857 | 1858 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper processed | 104,089 | 130,038.31 | 216,026.44 | 180,125.44 | 213,527.44 | 230,423.06 | 289.365.25 | 306,315.81 | 314,197.38 |

| Copper goods made | 102,203.25 | 127,813.25 | 213,504.38 | 163,520 | 194,342 | 228,961.13 | 184,103.75 | 300,583.25 | 310,304.63 |

| year | 1859 | 1860 | 1861 | 1862 | 1863 | 1864 | 1865 | 1866 | 1867 |

| Copper processed | 290,859.65 | 281,988.5 | 330,330.2 | 398,460.39 | 387,626.65 | 479,695.63 | 486,757.55 | 425,505.35 | 392,562.45 |

| Copper goods made | 286,689.35 | 277,706 | 324,849.4 | 393,314.65 | 382,004.2 | 466,869.63 | 476,623.58 | 415,331.8 | 385,008.5 |

At the beginning of the 20th century there was a progressive development to improve the rolling mill technology, which the company in Grünthal did not avoid. With the construction of a third rolling mill, this technology became a leader compared to other production processes in the company.

During the First World War, civilian production was quasi stopped, the level of armaments production increased to 215 percent during this time compared to the pre-war period. On the other hand, there was a rapid decline in production in 1918, which was due to a lack of raw materials and a refusal to work. After 1920, the production of metals - with the exception of alloys - no longer had a share in the operating result; their production was taken over by the state ironworks near Freiberg. Grünthal specialized in the manufacture of semi-finished products.

| year | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| quantity | 685.5 | 655.9 | 922 | 1,564.4 |

The plant in Auerhammer received orders from the military from 1933, which were initially implemented with copper sheets from the Grünthal plant. Armaments production itself took place later in Grünthal. With the transition to the war economy, the manufacture of consumer goods gradually faded into the background. The focus of arms production was on disks and pans for ammunition factories , the manufacture of light metal semi-finished products and, from 1942, ammunition disks for anti-aircraft guns . The Schweinitzmühle was converted to the production of iron powder and iron guide rings.

paragraph

Various paths were taken to sell the products. In some cases, production was left to an individual or a group of metal dealers as a privilege against the obligation to supply the factory with lead. After the Uthmanns had not been extended their privilege to sell the cookware after the factory was sold, metal wholesalers applied to the State Chancellery for one. It was only briefly awarded to wholesale merchants from Nuremberg in 1568. They had to request an extension every year. The state tried to tighten the conditions for this privilege steadily, whereupon the merchants waived in 1571. From the following year, the electoral treasurer took over the copper produced on his own account. At the top of the sale, the demand from the electoral foundry and armory and the coins were met. In the former, guns were ostensibly cast and utensils and jewelry were made. This was followed by the country's coppersmiths. Metal wholesalers and electoral officials such as Hans Harrer applied for the remaining quantities .

Sales to coppersmiths in the electorate were promoted in two ways. In addition to their obligation to purchase copper produced in Grünthal, the state's iron hammers were forbidden to make cooking utensils if they could be made of copper. From 1772 to 1775 there were also major sales difficulties for copper goods as a result of the Seven Years' War, which led to overcapacities and thus to production restrictions. To counteract this, hammered copper products were increasingly used. When the Saigern smelting processes, which had been in operation since the founding, were discontinued in 1853, no more silver was put on the market.

From the end of the 19th century, deliveries to the Saxon state took a back seat. To potential buyers to provide incentives for the purchase of copper goods from Grünthal, were Commission bearing set, which accounted for some transportation costs and the products could be offered in accordance cheaper. The first direct product advertising began in 1831. After 1840, the sales-promoting means of presenting Grünthal products at exhibitions were also increasingly used.

With the acquisition of the former Schweinitzmühle in Böhmisch Grünthal in 1883 and its expansion into an economically independent branch in what was then Austria-Hungary , local markets were opened up.

Due to the effects of the global economic crisis, the company joined the Central Association of the German Metal Rolling Mills and Metallurgical Industry in 1930. The management hoped this would protect itself from falling prices. However, in order to secure the existence of the company, the company was forced to become a member of the copper sheet syndicate and the brass pact in 1930 and of the German copper wire association in 1931 . V. The sales volumes of the respective product categories were regulated through these associations and the companies were allocated corresponding quotas.

From 1933 onwards there was an upturn in production, but this was based on orders from the military. The company worked in a non-ferrous metallurgy export group. Company representatives existed in 29 countries worldwide. With the transition to a war economy, civilian production gradually took a back seat, production losses of goods for the world market were overcompensated by armaments orders.

economics

The accounting books from 1586 onwards reveal a continuous profit up to 1648. Even the effects of the Thirty Years' War have only marginally diminished. The silver price remained constant in the aforementioned period, while the copper price tended to rise.

Between 1763 and 1789 the economy was characterized by severe sales difficulties for cookware; In contrast, in 1784 the factory had achieved an undisputed top position among the country's copper hammers. With 900 quintals (around 46.25 t), the four hammers sold almost twice as much as all the other hammer mills in the country put together. Even for the period up to 1789, surpluses are consistently reported, the increasing tendency of which is due partly to the smelting campaigns and partly to the considerably increased share of the further processing of copper produced in our own hammer mills.

The industrial revolution that progressed rapidly in Saxony after 1830 and the bourgeois reforms that began at the same time brought about drastic changes. Furthermore, the market became the determining factor for profitability. A quick reaction to the relatively rapidly changing boundary conditions was not possible due to the cumbersome procedures in the Saxon state economy. The prevailing principle of direction led to a loss of time compared to the up-and-coming competitors. Only when the new rolling mills went into operation did the situation gradually ease, as the product range could now be expanded significantly from an economic point of view.

Despite the general conditions that changed to a large extent after 1830, a continuous, albeit strongly fluctuating, surplus was reported for the period from 1790 to 1873.

The start-up crisis in autumn 1873 caused the upswing in production to stall. Inventories could not be sold, claims could not be collected due to the insolvency of customers. In addition, the new entry into the copper industry caused difficulties due to a lack of experience, and planned operating results did not materialize.

After the First World War, bottlenecks in the fuel supply turned out to be problematic. Two of the three rolling mills had to be shut down temporarily due to a lack of fuel. The loss of armaments-oriented production during the war was partially offset by the increased need for civilian products.

For cost reasons, the management of the plants in Auerhammer and Grünthal in Aue was merged from July 1930. The company also applied for loans from the cities of Aue and Olbernhau . The city of Olbernhau approved 25,000 Reichsmarks . However, these measures could not stop the economic downtrend. The losses at the Grünthal and Auerhammer plants amounted to 2.7 million RM according to the closing balance for 1930. With the help of the Saxon Ministry of Economics, a settlement was reached: liquidation of both plants and transfer to a stock corporation. The original owners retained a share of 100,000 RM (today around 372,000 euros) in ordinary shares , and all properties were brought into a company in liquidation for the purpose of being sold. On July 2, 1931, the stock corporation was founded in Leipzig.

From 1933 onwards, the economic situation improved thanks to orders for the military. The export turnover increased from 730,000 RM in 1933 to 1,644,000 RM in 1938.

Community and community of Kupferhammer-Grünthal

Emergence

Located at a relatively large distance from the nearest town of Olbernhau, the iron and steel works was probably already an independent community when it was founded, at the latest under the leadership of the Uthmanns. When the plant was founded, eight residential buildings were built for the workers and employees due to the remote location.

Privilege for self-sufficiency and appropriate facilities

One of the privileges granted to the plant was the right to self-sufficiency for the workforce and residents. The existence of a grinding mill was of vital importance. Although the Hüttenmühle is only mentioned in a document in the purchase contract between the elector and Uthmann's heirs dated August 6, 1567, it is most likely that it was built 30 years earlier when the factory was built. The grinding mill was given up in 1882, after the requirement to cover the needs of the ironworkers via the local grinding mill had expired.

The owner of the hut had also been granted brewing and licensing rights for his territory. He was not allowed to serve in surrounding places. The brewing right was initially not exercised for almost three decades. It was not until 1586 that the Kleine Hammer was decommissioned and converted into a brewery. The licensing right was transferred to the shift supervisor in 1587, who from then on exercised it in the new shift supervisor's house. After the licensing law was reorganized in 1612 and a tavern was named, the term hut tavern appeared in the documents for the first time in the same year . Brewing and licensing law not only had the advantage of being close to the ironworkers, but also of being exempt from drinking tax . The relatively low capacity and the necessary supervision by the trade office made the own beer production in the 19th century unprofitable for the now private company management, so that the operation was finally stopped soon after the purchase of the factory equipment. The licensing rights were now held by the new factory owners, who from then on were also allowed to sell to non-residents.

With the bars in the was room house based Fleischbank connected. Around 1900, the Lange family expanded agriculture on their own lands into a branch of their own. Meat products and other products such as potatoes, milk, etc. were sold to the workforce at a discount. After the school moved out of the old factory, the vacant rooms were converted into a goods delivery point and a consumer association was founded for the workforce. The purchase was pre-financed by the factory, and the profit was split at Christmas time.

Medical supplies

A survey from the 18th century states that a Physicus is said to have been installed soon after it was acquired by the Electorate in 1567 . However, this can only be proven after 1611, after which the Bergphysicus from Freiberg treated in Grünthal. This was subordinate to the Oberbergamt and had to go to Grünthal immediately if necessary and at the request of the smelter factor. While the Physicus predominantly diagnosed and checked, the mostly settled - and therefore quickly accessible - surgeon took over the treatment of the patients in Olbernhau .

In 1811 the office of Bergphysicus was separated from the Physicus of the Saigerhütte. This was the first time that a doctor was employed in the iron and steel works. By a law of July 10, 1836, the health system was broken from feudal ties and district doctors were installed in the Kingdom of Saxony.

jurisdiction

The lower jurisdiction was associated with the enfeoffment of land for the iron and steel works . It related to the property of the plant and its residents, labor law, conflicts between residents and legal representation in cooperation with other courts and offices. If disputes could not be settled, initially the tenth from Annaberg and later the Oberbergamt in Freiberg were the next higher instance.

The Saxon rural community ordinance issued on November 7, 1838 abolished the communities' own jurisdictions, but at the same time left these administrative rights to the landlords. The patrimonial legislation was abolished on the basis of the Courts Constitution Act of August 11, 1855. Since Grünthal was a municipality, the Zöblitz office lifted its jurisdiction in 1859.

After feudal ties had already been removed by the Trade Act in 1861, it was not until the General Mining Act of June 16, 1868 that the feudal mining legislation was finally broken away. Although the law on shelf mining of May 22, 1851 had replaced all previous legal provisions and thus the mining regulations of Elector Christian of June 12, 1589, at the time it still adhered to the principle of management .

School system

The plant management's interest in school education resulted from the work tasks of the ironworkers, which required knowledge of arithmetic, reading and writing. The earliest known news about a school dates from 1589. The rights of the hut factor included patronage over the school and the attitude of the teacher. The fact that school fees were not levied helped to encourage regular school attendance - which, according to the church and school regulations of 1580, was not an obligation, but a recommendation. The work took over the costs of teaching and maintaining the school house. The school building is noted in 1606 as "the old cattle house where the teacher lives". In the old cattle house at the Unteren Tor , a room had been converted for teaching and a teacher's apartment had been set up.

With the School Act for the Kingdom of Saxony enacted on June 6, 1835 , the school system was henceforth a public affair and fell under the jurisdiction of the municipality, which was responsible for the accommodation and remuneration of teachers and the maintenance of the school building. Regular school attendance became compulsory from 6 to 14 years of age. Due to the special position of the district of Grünthal, the patronage right of the hut factor remained unaffected, but he exercised it as a member of the school board. After the local school inspector had characterized the premises as dilapidated and untenable in 1848, the move took place the following year. In the old trading post, two classrooms were set up on the ground floor and the teacher's apartment above. The plant reluctantly maintained the rooms. As a result of the lower number of pupils, the Mining Authority considered closing the school in 1853, which it hoped would save costs. A subsequent increase in the number of pupils - in addition to Grünthal, there were also pupils from Oberneuschönberg, Olbernhau, Hirschberg , Leinitzdörfel (= Dörfel, today a district within the city of Olbernhau), Niederseiffenbach , Kleinneuschönberg and Rothenthal - made it necessary to build a new school. After the site of the former brickworks became vacant, the factory management at the time made it available as a building site. The new building, erected in 1884 and 1885, was inaugurated on February 1, 1886. The majority of the students came from Olbernhau as early as the mid-1920s. Even after the patronage over the school had long since expired, the company appeared until the mid-1920s with foundations and gifts to schools and students. Students from the community of Kupferhammer-Grünthal also enjoyed freedom from learning materials . Due to the poor state of local finances in the years of the Great Depression of 1931, the learning material were canceled for children full employee and the supplement for teaching and learning aids of 450 reduced to 250 RM. On December 23, 1936, the school district of Kupferhammer-Grünthal was incorporated into the city of Olbernhau, breaking all ties between the plant and the school.

Municipality of Kupferhammer-Grünthal

When the first Saxon constitution of 1831 came into force , there were significant changes for the Saigerhütte: Feudal orders and legal conceptions were successively eliminated, which resulted in, among other things. reflected in labor law, community code and jurisdiction. The local structure was reorganized with the Heimatgesetz of 1834. Grünthal pushed through the establishment of an independent home district. Its development and management was closely linked to the iron and steel works right up until the end.

| year | 1834 | 1871 | 1875 | 1890 | 1905 | 1910 | 1925 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| population | 162 | 167 | 189 | 279 | 483 | 496 | 458 |

The onset of the global economic crisis led to a deteriorating economy and caused great problems for the company. In order to stop the threatened bankruptcy, it requested financial support from the city of Olbernhau, in return the union of the municipality with the city was offered. However, the residents of Grünthal did not agree, they rejected this proposal at a residents' meeting on July 11, 1931. Another attempt to incorporate it into Olbernhau was made in 1935 on the instructions of the governor in Marienberg. In this case, F. A. Lange Metallwerke AG Aue resisted. She had reached the profitability zone again and saw economic advantages in the continued existence of the community. On October 28, 1936, the NSDAP Gauleiter of Saxony, Martin Mutschmann, ordered the incorporation into Olbernhau on April 1, 1937. The negotiations on this led to unsatisfactory results, which is why Mutschmann then took the opportunity offered by the municipal code: He forced the merger. The contract was concluded, and Kupferhammer-Grünthal brought its municipal assets to the city of Olbernhau.

Today Grünthal is a district within the city of Olbernhau.

List of functionally connected buildings in the hut complex

![]() Map with all coordinates of the listed buildings: OSM

Map with all coordinates of the listed buildings: OSM

| Illustration | description | Location | Story / remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old trading post | 50 ° 38 '59.16 " N , 13 ° 22' 3.9" E | The building was erected in 1604 as a residential building for Factor Eymer, which gave it the name of a trading post and later an old trading post.

After the local school inspector had characterized the classrooms in the Zimmerhaus as dilapidated and untenable, they were moved here in 1850. The school was housed here until the inauguration of a new building on February 1, 1886. After the school moved out, the vacant rooms were converted into a goods delivery point and a consumer association was founded for the workforce. The building is currently used commercially. |

|

| Old hammer | 50 ° 39 '0.36 " N , 13 ° 22' 12.07" E | ||

| Workers' house / "shift master house" | 50 ° 38 '59.22 " N , 13 ° 22' 7.08" E | Since the establishment of the plant, the owners have made it a point to locate their workers in the immediate vicinity. The houses were handed over to the users - mostly one or two families - free of charge in return for the obligation to maintain the interior furnishings. The buildings were usually one-story and were located near the production facilities for reasons of safety and fire protection / fire fighting. The four surviving workers' houses are located in a row of houses from the long hut to the upper gate. A museum is currently housed in the “Seiferthäuschen”. All other buildings are still used today as residential buildings, with an additional shop for handicrafts located in the "shift master's house". | |

| Workers house | 50 ° 38 '59.29 " N , 13 ° 22' 7.82" E | ||

| Workers house | 50 ° 38 '59.53 " N , 13 ° 22' 9.47" O | ||

| Workers' house / "Seiferthäuschen" |

50 ° 38 '59.32 " N , 13 ° 22' 8.59" E | ||

| Brewery | 50 ° 38 '55.95 " N , 13 ° 22' 8.41" O | In 1586 the Kleine Hammer was decommissioned and converted into a brewery. It served as a brewery until the 19th century, later it was used as a carpentry shop. The building is currently unused. | |

| Electric power station | 50 ° 38 '56.07 " N , 13 ° 22' 9.67" O | The building was erected in 1904/1905, inside two Francis turbines with corresponding generators generated electrical energy. The impact water brought about by Rothenthal was fed through a pipe from the light house under the lower pond. A Lanz locomobile was available for times when there was little water . The premises can currently be rented for festivities of various types and sizes. | |

| Forester's House | 50 ° 38 '59.29 " N , 13 ° 22' 12.16" E | The forester's house was built in 1610 for the forester Hans Seidenschwanz. The land belonged to the Lauterstein office , to which rent was paid. The location on the Natzschung in front of the upper gate was chosen because the raft place was in the immediate vicinity. The forester was responsible for overseeing it. The building was used as a residential building until 2010 at the latest, but has been vacant since then. | |

| Cooking house | 50 ° 39 '2.45 " N , 13 ° 22' 7.15" E | The cooking house was built in the 1560s under the leadership of the Uthmanns, which means that the refining processes, ie the cooking and drying of the copper, could be outsourced from the Lange Hütte. Until 1990 the rooms were used as a carpentry shop. The building is currently used as a residential and commercial building for a bicycle shop. | |

| Big cabbage house | 50 ° 38 '58.53 " N , 13 ° 22' 9.09" O | The original building from the 16th century was used to store charcoal and firewood. In 1854 the building was expanded using solid construction. Part of the old curtain wall is contained in the current building fabric. Currently used as a bowling alley. | |

| The courtman's house | 50 ° 38 '59.79 " N , 13 ° 22' 5.97" E | The building was rebuilt in 1587 and was called the new shift master house for a while. Before that, he lived in the hut tavern , which was called this from 1612 onwards

Private individuals expanded the house of the dresser together with the hut tavern until 1997 into the Hotel Saigerhütte . |

|

| House of Judge Lange | 50 ° 39 '0.68 " N , 13 ° 22' 4.52" E | The house was built in 1611 - the year has been preserved to this day in the beams above the entrance door - opposite the old shift foreman house. The then hut judge Christoph Lange moved into it. The term “judge's house” was coined for it, although it did not contain an official apartment and later judges also lived in other buildings. The building is still used today as a residential building. | |

| Hut mill | 50 ° 39 '2.94 " N , 13 ° 22' 8.58" E | Although a grinding mill is only mentioned in a document in the purchase contract between the elector and Uthmann's heirs dated August 6, 1567, it is most likely that it was built 30 years earlier when the plant was built. From 1696 the grinding mill was leased to secure additional income. The building burned down in 1742 and was then rebuilt. The mill was in 1817 in long lease , 1842 since 1827 related leasehold Müller owner was the mill. He now only had to pay the basic interest to the state. The grinding mill was given up in 1882, after the requirement to cover the needs of the ironworkers via the local grinding mill had expired. The miller converted the building into a wood goods factory, which, however, was not in operation for long. The owners of the iron and steel works bought the building in 1894, and after 1945 the building was converted into a residential building and from 1986 into a residential building with a café. The café was closed at the end of 2017. | |

| Hut tavern | 50 ° 38 '59.68 " N , 13 ° 22' 4.57" O | In 1587 the shift supervisor, who had previously lived here, moved to the new shift supervisor's house. From this move on, the building was given the name of the old shift master's house. Only after the pub law was re-regulated in 1612, when a tavern was called and the bar was now being served here, did the term hut tavern appear in the documents for the first time. The hut tavern was leased to a private person from 1857 to 1896, after which it became a works canteen under company management.

Private individuals expanded the hut tavern together with the house of the dresser to become the Hotel Saigerhütte by 1997 . |

|

| Smithy | 50 ° 39 '0.74 " N , 13 ° 22' 9.23" E | The building was erected in the period from the middle to the end of the 16th century as a forge for ironware, and there were other living and utility rooms in the house. In 1765 the building burned down and was later rebuilt. In 1867 the blacksmith's workshop was closed and the building was converted into a house for three families. In the second half of the 20th century, the sheet rolling mill in Olbernhau also used it to store equipment for civil defense . At the end of the 1980s, the building became the property of VEB Hochbau, which traded as Hochbau GmbH after the political change. However, the substance of the building increasingly fell into ruin. In 2004 it was acquired by the owners and operators of the Saigerhütte hotel from the bankruptcy estate of Hochbau GmbH, which went bankrupt in 2000. After several years of preparatory work, the building was finally rebuilt in 2014 with the help of subsidies. The historical foundation walls and barrel vaults inside could be preserved. | |

| Bowling alley | 50 ° 39 '0.89 " N , 13 ° 22' 3.44" E | Built in 1881 for the employees of the Saigerhütte - preferably the civil servants. Remnants of the curtain wall are still present in the fabric of the building. Of the bowling alley, only the meeting room / salon is preserved. The bowling alley adjoining the head building was demolished in 2002. The building is currently used as a warehouse. | |

| Coach house | 50 ° 39 '1.29 " N , 13 ° 22' 6.16" E | Built in 1907 as a stable / residential building for the coachman. Currently used as a residential building. | |

|

|

Long hut | 50 ° 38 '58.38 " N , 13 ° 22' 6.03" E | The Lange Hütte was initially the central production location for all essential process steps. The inventory included, among other things. Fresh and melting furnaces, Saiger and driving hearths, drying and cooking furnaces as well as the laboratory as a separate room with devices and tools for trying out pieces of metal to be processed.

In 1562 the building was rebuilt. the year 1562 indicated in the sandstone portal on the gable side. This shows that the previous building from 1537 must have been worn out. The building was demolished in 1952 because it was in disrepair, the site was filled in and leveled for a parking lot. From 1992 to 1994 the foundations were exposed again and the technology as the Saigerhütte open-air museum was partially reconstructed. The inauguration took place during the 2nd Saigerhüttenfest from June 3rd to 4th, 1994. |

| New trading post | 50 ° 38 '56.56 " N , 13 ° 22' 5.94" E | This is the large multi-storey residential building that towers over the entire area of the Saigerhütte.

The original middle section of the building was erected in the 1560s under Uthmann's leadership. 1586/87 was added to the gable, since then a sandstone relief with the year 1586 and the name of Elector Christian I has been emblazoned above an entrance. Finally, in 1628 another extension was built on the opposite side of the gable, for which, despite the chaos of war, large celebrations, among others. took place with a visit from the Elector Johann Georg I. including the court. Apart from the short-term use of today's old trading post from 1606 to 1628, the building served as a trading post until 1873. In 1802/1803, after the stables on the west gable were demolished, the three-storey extension of the western part with an entrance from the gable took place. The electoral coat of arms with the year 1803 comes from this extension. After a fire in 1967, it was rebuilt as a residential building. In this building there are exhibition rooms in which visitors can see traditional handicrafts from the Erzgebirge such as engraving on glass, bobbin lace, weaving and braiding. |

|

| Neuhammer | 50 ° 39 '3.78 " N , 13 ° 22' 5.11" E | The Neuhammer was built in 1586/87 to replace the small hammer that had been converted into a brewery. The water required for operation was supplied by a ditch that was branched off from the wetland. The hammer mill had two 4,285 Lachter (approx. 8.5 meters) large, undershot water wheels. Two opening and one spreading hammer as well as two bellows for the forge fire were driven by water power. An extension housed the coppersmith's accommodation with three rooms.