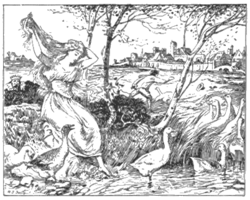

The goosemaid

The goose girl is a fairy tale ( ATU 533). It is in the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm at position 89 (KHM 89).

content

A queen, whose husband died long ago, sends her only daughter far away to marry a king's son. She gives her a maid, a talking horse named Falada and, as a travel talisman, a cloth with three drops of her blood. The daughter loses this cloth when she has to bend over a stream because the maid refuses to give her water with the golden cup. The maid even forces the princess to swap horses and clothes and then makes her swear not to tell anyone about it. The princess humbly tolerates all of this. When they arrive at the castle in reversed roles, the prince receives the maid as his bride, and the old king sends the king's daughter and a little boy named Kürdchen to look after the goose. The false bride has the head of the horse Falada chopped off because she is afraid of being betrayed by him, but at the request of the king's daughter the butcher nails her head over the gate through which she and Kürdchen go daily with the geese. There, the princess talks to the horse's head every time she walks past, which she calls "maiden queen". On the goose meadow she opens her shiny golden hair in order to braid it again, and Kürdchen tries to pull out some of her hair. But she speaks a spell with which she causes a gust of wind that blows the little hat off the head. He has to run after him and by the time he comes back she will have done the hairstyle. Kürdchen complains to the king, and he secretly observes the two of them the following day, and finds everything, as reported by Kürdchen. In the evening he takes the king's daughter aside and demands an explanation. But she refuses to speak with reference to the oath she had taken. Then the king lets her complain of her suffering to the stove and overhears her unnoticed. The prince learns the truth. The king lets the false bride speak her own judgment, and she is dragged to death in a nailed barrel. A magnificent wedding is celebrated.

Stylistic peculiarities

In this fairy tale, the three talking drops of blood appear supernaturally and then the talking horse's head, whereupon the king's daughter herself unfolds magical influence on the wind with a saying. The drops of blood only speak twice: “If your mother only knew that, her heart would burst” before falling into the water. The other two formulas are repeated three times each:

- "O you Falada, since you are hanging"

- "O you maiden queen, since you walk,

- if your mother only knew

- her heart would burst. "

The address with "O you" and the rhyme with the dark 'a' give the first two lines their dignified, melancholy character. In the other two lines, Falada speaks like a drop of blood, but the addition “in the body” is missing . The wind poem after that sounds brisk and bright:

- "Woe, woe, diaper,

- take Kurdchen's hat,

- and let yourself be hunted

- until I braided myself and chatted,

- and put it back on. "

Only when she complains in the oven does the princess close herself this time with the text of the drops of blood: "If my mother only knew that, her heart would burst" (from 1843, cf. KHM 6 , 56 , 166 ).

interpretation

A "snitch" is a topknot that was tied around the head from two plaited braids to form a bun, and the hood was placed on top. The text clearly identifies itself as a fairy tale by describing magical processes as a matter of course, without any surprise among those involved. As in many fairy tales, the heroine has to pass a test of her steadfastness and tolerance. She succeeds in doing this by clinging to her broken ties to her homeland, for which the severed head of the horse and the mother's blood stand as pars pro toto . The story is understood as a development fairy tale. Despite her dignity, the princess lacks strength, in contrast to the selfish and unscrupulous maid. The conflict begins at the stream with the mother's (liquid) drops of blood and then ends in the father-in-law's (hard) iron furnace. Both symbols express the warmth of the heart, with a simultaneous contrast between the elements water and fire. In between, the horse's head hung high, the hair care and the wind express a head-heavy and coolness. Like the river before, the gate also indicates a transition. Her father-in-law instructed her to walk with the geese (cf. The goose-girl at the fountain ), while at the beginning the mother of the fatherless girl dominated. The harsh punishment of the maid tolerated by the mother also fits this contrast.

According to Hedwig von Beit's deep psychological interpretation, the light of consciousness is expressed in the golden hair (see Der Eisenhans ), framed by the still playful shepherd boy and the father-image of the old king. The horse is an image of the Great Mother , who increasingly breaks up into opposing women on the way to consciousness. The red and white blood flap as the physical preliminary stage of the self unifying the opposites ensures both reconnection and orientation. His loss in the face of the thirst for life is followed by passivity and revaluation (horse and clothing exchange). Three is also the number of the initiative. Like many others, the fairy tale has three sections, with a fourth as the end. Other authors find the ambivalent interpretation of the mother exaggerated here because there is no symbolic connection to the maid and the horse swap rather parallels the bridegroom's transition. Bruno Bettelheim sees an Oedipus conflict in two opposing aspects: a child thinks that the same-sex parent has cheated out of the affection of the other and later realizes that it is the usurper himself. The fairy tale illuminates the dangers of long-term clinging to childish dependence. The heroine transfers her dependence on her mother to the maid and is thus again a young, unmarried girl. Herding with a little boy emphasizes immaturity. But she defends her golden hair, unlike the gold cup. She learns to be herself and keeps the oath once taken. The false bride, on the other hand, wants to appear as someone she is not. The punishment is important, it gives a child security. The white bridal horse is appropriately avenged by white horses. Bettelheim compares Roswal and Lillian , to the bloody white linen as a symbol of sexual maturity also the cloth with the three drops of blood .

Heinz-Peter Röhr diagnoses a dependent personality disorder in the princess, who is spoiled by her mother and ultimately devalued as a maid. Conversely, this corresponds to a narcissism in the maid and helm. Wilhelm Salber observes that conscious and unconscious activities are kept separate in order to avoid conflicts. Such people are busy trying to avoid the betrayal they are secretly seeking. The psychotherapist Jobst Finke describes the course of therapy for a civil servant with agoraphobia and panic attacks . She felt constrained in her marriage and would have wished for such an intimate connection to her mother, a father figure who understood without her involvement and a listening friend like Falada, also enjoyed the princess' flirting with the shepherd boy.

Origin and Distribution

The fairy tale is known from the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm , where it is included in position 89 from the second part of the first edition in 1815 (since no.3). Since then, only minor changes have been made to the wording. According to Jacob Grimm, he followed an oral story he recorded by Dorothea Viehmann , an innkeeper from a Huguenot family in Niederzwehren (in Hesse , near Kassel ). As always, the Grimms tried to connect elements of the fairy tale, especially with regard to the role of the horse, with old Germanic mythology (see also KHM 126 Ferenand Tru and Ferenand ungetrü , KHM 136 Der Eisenhans ). The horse in Roland's song is called Veillantif ( Valentich , Valentin , Velentin ), and that of Willehalm is called Volatin ( Valatin , Valantin ).

Hans-Jörg Uther finds the French Bertasage and Le doje pizzelle from Giambattista Basiles Pentameron (IV, 7) as precursors . According to Lutz Röhrich , the horse was considered to be mind-sighted in popular belief . He also finds examples of the importance of the drops of blood. In KHM 56 The Dearest Roland , they answer instead of the slain daughter. In popular French versions, a voice warns Little Red Riding Hood when she is supposed to drink her grandmother's blood: You are drinking my blood . Also in KHM 88 The Singing, Jumping Lion's Neck , drops of blood lead to a relative on the other side. In Genesis 4:10, God said to Cain : The voice of your brother's blood cries out to me from the earth . Sayings of the voice of the blood or the bonds of blood exist to this day.

Ruth Bottigheimer from the Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales finds many oral versions of the fairy tale almost worldwide. Apparently the common thread remains quite stable even when mixed with others. Instead of the horse's head, which is common in the German-speaking area, other animals ( donkey , dog , birds ) can appear. The drops of blood can be replaced by tears or golden hair from the mother, a brooch, a cloth or a golden apple. The marriage trip is less often modified as a family visit or the like. Similar fairy tales are those of the good and bad girl (KHM 11 Little Brother and Sister , KHM 13 The Three Little Men in the Forest , KHM 135 The White and Black Bride ). The false rival also appears in various fairy tales towards the end (KHM 21 , 65 , 88 , 113 , 126 , 127 , 186 , 193 ). Cf. in Giambattista Basiles Pentameron I, 2 The Little Myrtle and IV, 7 The Two Little Cakes .

effect

Heinrich Heine became related to verses 29 to 48 in Germany through the fairy tale that his wet nurse told him as a child . A winter fairy tale (Caput XIV) and perhaps also inspired the poem Die Lore-Ley . The writer Rudolf Wilhelm Friedrich Ditzen chose his pseudonym Hans Fallada after Hans im Glück and the horse Falada from The Goose Girl . Bertolt Brecht's poem A Horse Accuses has the subtitle Oh Falladah, you hang! . It was set to music by Hanns Eisler . The fairy tale had a particularly intense and differentiated reception history in English-speaking countries (see The Goose Girl in English-language Wikipedia) and, since the 1980s, in Italy too. Numerous fantasy novels took fairy tales as their plot template. Margaret Mahy uses the fairy tale phrase "If you don't want to tell me anything, complain to the iron stove for your suffering" in her youth book The Other Side of Silence about a girl who refuses to speak , who last wrote a book and burned it in the stove. The goose girl is also a character in the second volume of the Manga Ludwig Revolution by the Japanese comic artist Kaori Yuki , inspired by Grimm's children's and house fairy tales ; there, however, the original narrative is completely dissolved.

Film adaptations

- 1957: The Goose Girl , feature film , West Germany , 73 min, director: Fritz Genschow

- 1977: The Goose Girl , feature film, Switzerland, 25 min, director: Rudolf Jugert

- 1986: The Goose Girl , animation film , GDR , DEFA film, 11 min, director: Horst Tappert

- 1988: The story of the goose princess and her faithful horse Falada , feature film, GDR , DEFA film, 80 min, director: Konrad Petzold

- SimsalaGrimm , German cartoon series 1999 , season 2, episode 26: The goose girl

- 2009: The Goose Girl , fairy tale film from the 2nd season of the ARD series Eight in One Stroke , Germany, 60 min, director: Sibylle Tafel

literature

Primary literature

- Grimm, Brothers: Children's and Household Tales . Complete edition. With 184 illustrations by contemporary artists and an afterword by Heinz Rölleke. Pp. 443-453. 19th edition, Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf and Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-538-06943-3 .

- Grimm, Brothers: Children's and Household Tales. Last hand edition with the original notes by the Brothers Grimm. With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin, not published in all editions, published by Heinz Rölleke. Volume 3: Original Notes, Guarantees of Origin, Afterword. Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition, Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-15-003193-1 , pp. 168–170, 481.

Secondary literature

- Bottigheimer, Ruth: Horse head: The talking horse head. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 10. pp. 937-941. Berlin, New York, 2002.

- Henkel, Nikolaus: lizard. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3. p. 1152. Berlin, New York, 1979.

- Moser-Ruth, Elfriede: Eideslist. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3. P. 1155. Berlin, New York, 1979.

- Alvey, Gerald: Iron. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 3. pp. 1294-1300. Berlin, New York, 1979.

- Röhrich, Lutz: Fairy Tales and Reality. Wiesbaden, second expanded edition 1964. pp. 66, 82.

- Rusch-Feja, Diann: The Portrayal of the Maturation Process of Girl Figures in Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm. European Publishing House of Science, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-631-47837-2 , pp. 102-118.

- Bluhm, Lothar and Rölleke, Heinz: "People's sayings that I always listen to". Fairy tale - proverb - saying. On the folk-poetic design of children's and house fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. New edition, S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-7776-0733-9 , pp. 107-108.

- Wilkes, Johannes: The influence of fairy tales on the life and work of Heinrich Heine. An investigation on the occasion of the poet's 200th birthday. In: fairytale mirror. Journal for international fairy tale research and fairy tale care. February 1997. pp. 9-12. ( ISSN 0946-1140 )

- Uther, Hans-Jörg: Handbook to the children's and house fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm. Origin - Effect - Interpretation. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , pp. 203-206.

Interpretations

- von Beit, Hedwig: Symbolism of the fairy tale. Pp. 778-789. Bern, 1952. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

- Kast, Verena: Paths out of fear and symbiosis. Fairy tales interpreted psychologically. 1st edition. Walter-Verlag, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-530-42100-6 , pp. 37-61.

- Röhr, Heinz-Peter: Ways out of addiction. Overcoming destructive relationships. 3rd edition, Patmos Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-423-34463-0 .

- Lenz, Friedel: Visual language of fairy tales. 8th edition. Free Spiritual Life and Urachhaus GmbH, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-87838-148-4 , pp. 133-145.

- Bettelheim, Bruno: Children need fairy tales. German by Liselotte Mickel and Brigitte Weitbrecht. 3rd edition, dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-423-01481-4 , pp. 157-165. (American original edition: 'The Uses of Enchantment', 1975)

Web links

- Märchenlexikon.de on The Replaced Bride AaTh 533

- Drawing by Adrian Ludwig Richter for Die Gänsemagd

- Interpretation by Daniela Tax of Die Gänsemagd

- SurLaLuneFairyTales.com: fairy tale text with commentary (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bluhm, Lothar and Rölleke, Heinz: "Speeches of the people, to which I always listen". Fairy tale - proverb - saying. On the folk-poetic design of children's and house fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. New edition, S. Hirzel Verlag, Stuttgart / Leipzig 1997, ISBN 3-7776-0733-9 , pp. 107-108.

- ↑ by Beit, Hedwig: Symbolik des Märchen. Pp. 778-789. Bern, 1952. (A. Francke AG, publisher)

- ^ Rusch-Feja, Diann: The Portrayal of the Maturation Process of Girl Figures in Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm. European Publishing House of Science, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-631-47837-2 , pp. 107-108.

- ↑ Bruno Bettelheim: Children need fairy tales. 31st edition 2012. dtv, Munich 1980, ISBN 978-3-423-35028-0 , pp. 157-165.

- ^ Röhr, Heinz-Peter: Ways out of the dependency. Overcoming destructive relationships. 3rd edition, Patmos Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-423-34463-0 .

- ^ Wilhelm Salber: fairy tale analysis (= work edition Wilhelm Salber. Volume 12). 2nd Edition. Bouvier, Bonn 1999, ISBN 3-416-02899-6 , pp. 106-108.

- ^ Jobst Finke: Dreams, Fairy Tales, Imaginations. Person-centered psychotherapy and counseling with images and symbols. Reinhardt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-497-02371-4 , pp. 157, 178-186, 192, 195, 202, 203.

- ↑ Grimm, Brothers: Children's and Household Tales. Last hand edition with the original notes by the Brothers Grimm. With an appendix of all fairy tales and certificates of origin, not published in all editions, published by Heinz Rölleke. Volume 3: Original Notes, Guarantees of Origin, Afterword. Revised and bibliographically supplemented edition, Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1994. ISBN 3-15-003193-1 , pp. 168–170, 481.

- ↑ Uther, Hans-Jörg: Handbook to the children's and house tales of the Brothers Grimm. Origin - Effect - Interpretation. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-11-019441-8 , p. 204.

- ^ Röhrich, Lutz: Fairy tales and reality. Wiesbaden, second expanded edition 1964. p. 82.

- ^ Röhrich, Lutz: Fairy tales and reality. Wiesbaden, second expanded edition 1964. p. 66.

- ↑ Bottigheimer, Ruth: Horse head: The speaking horse head. In: Encyclopedia of Fairy Tales. Volume 10. pp. 937-941. Berlin, New York, 2002.

- ↑ Wilkes, Johannes: The influence of fairy tales on the life and work of Heinrich Heine. An investigation on the occasion of the poet's 200th birthday. In: fairytale mirror. Journal for international fairy tale research and fairy tale care. February 1997. pp. 9-12. ( ISSN 0946-1140 )

- ↑ Text on erinnerorte.de ( Memento of the original from February 21, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Margaret Mahy: The Other Side of Silence. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-423-70594-9 , p. 263 (translated by Cornelia Krutz-Arnold; New Zealand original edition: The Other Side of Silence ).