al-Fārābī

Abū Nasr Muhammad al-Fārābī ( Arabic أبو نصر محمد الفارابي, DMG Abū Naṣr Muḥammad al-Fārābī , short Farabi , al-Farabi or Alfarabi , Latinized Alpharabius or Avenassar ; born probably around 872 in Otrar , Siebenstromland ; died 950 between Ashkelon and Damascus , Syria ) was an Islamic philosopher and scholar from Central Asia .

Life

Especially about al-Fārābī's childhood and youth, neither written-documentary nor written-narrative sources offer any clear facts. As the son of a general, his place of birth was possibly Wāsij, a small fortress in the Fārāb district on the northern border of Transoxania or the Faryab region in present-day Afghanistan . The biographical sources, which are much later and largely not directly reliable, contain various information about his ethnic origin from Central Asia . a. an Iranian , Turkestan or Turkish ancestry, although the research literature largely considers the latter to be more likely or a conclusive judgment to be unfounded. Al-Fārābī states that one of his philosophical teachers was the Nestorian Christian and follower of the Alexandrian school Yuḥanna ibn Ḥaylān (died around 920). Since he moved to Baghdad in 908 , it is assumed that al-Fārābī also stayed there from this point in time at the latest. Furthermore, al-Fārābī had connections to Abū Bišr Mattā ibn Yūnus, a translator and commentator of the Baghdad school of Christian Aristotelian . From 942 al-Fārābī then lived mostly in Aleppo in the allegiance of the later Hamdanid prince Saif ad-Daula . In the year 950 he is said to have been killed by road robbers as a companion of Saif ad-Daula on the way between Damascus and Asqalān, according to the legendary depiction of al-Bayhaqīs (approx. 1097–1169).

Little is known about al-Fārābī's life in Baghdad. There are many anecdotes in general about his life that present him as an unworldly scholar. For example B. an account of al-Fārābī's alleged night watchman activity in a Baghdad garden, since he found the necessary peace and quiet to think about during the night. Anecdotes about his appearances as a musician portray him as a musical seducer of groups of people who were “enchanted” by al-Fārābī; B. played to sleep against their will etc. The truthfulness of these anecdotes is to be viewed rather critically, although certain points may have corresponded to reality. This cannot be verified, however, since al-Fārābī, in contrast to other prominent contemporaries, did not write an autobiography and neither did his students report about his life.

plant

He dealt with logic , ethics , politics , mathematics , philosophy and music . Among other things , he was familiar with philosophical works by Aristotle (along with some important commentaries) and Plato , which he already had in Persian or Arabic translations, and he also promoted the translation of other texts.

He was of the opinion that philosophy had now found its new home in the Islamic world. He considered philosophical truths to be universally valid and regarded the philosophers as prophets who had come to their knowledge through divine inspiration (Arabic waḥy ).

Musicology

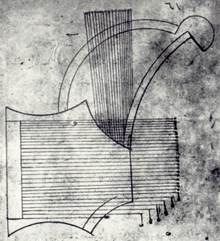

His Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr (Great Book of Music) is considered to be the most comprehensive and fundamental work of the “Iranian-Arabo-Turkish” music theory and music systematics. In his writings on music he combined detailed knowledge as a practicing musician close to Sufism and objective precision as a scientist with the logic of philosophy. The musical instruments he describes include the zither-like string instrument šāh-rūd and the long-necked lute tanbur ( ṭunbūr al-baghdādī and ṭunbūr al-chorassānī ), with which he uses drawings to describe characteristic features of keys, modes and intervals. The short-necked lute ʿūd was central to al-Fārābī . Al-Fārābī himself is reported to have often played these lutes at ceremonial events. There are some anecdotes about this, but they are difficult to prove.

Al-Fārābī began his most important music theoretical treatise, the Kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr , on the occasion that the traditional Greek works were in his opinion of inferior quality. He attributed this to incorrect translations. He also found views among Arab music theorists that either were not applicable to the conditions of Arab music or lacked a theoretical background. So had z. B. al-Kindī transferred Greek theory to Arabic music. Al-Kindī himself lacked practical knowledge of music in order to be able to determine the lack of applicability of Greek music theory to the Near East. He adopted a large part of Greek vocabulary from a wide range of scientific disciplines, but set certain points between Greek music theory and the music of the Orient.

Al-Fārābī distinguishes the philosophical theory of music from acoustics. He divides the craft of music into 3 arts (fann) Sawa, the first art is the knowledge of theory such as the acoustics of the interval theory of melody and rhythm. In his opinion, the Greeks limited themselves to this art. The second art, according to al-Fārābī, is the knowledge of instruments and the making of tones on them, i.e. learning to play an instrument, the connection between theory and practice. Al-Fārābī makes special reference to short-necked and long-necked lutes, flute ( nay ), oboe ( mizmar ) and harp ( tschang ) as well as a few other instruments. The third art deals with the theory of composition itself. Here al-Fārābī goes into consonance and dissonance and deals with melody and rhythm. The part of his work that deals with the melody is difficult to understand. According to al-Fārābī, the rhythm represents the length and expansion of the notes. Al-Fārābī uses borrowings from Euclid's geometry for a more detailed description of tones. Analogous to human language, music exists both in rhythmic, “poetic”, and non-rhythmic form. The latter is characterized by the fact that the individual notes do not have a fixed length.

medicine

In the medical field, a core point of the Farabian structure of thought reveals itself again, namely the recourse to a central, all-regulating element, also known as monarchism . Farabi counted as natural science only knowledge of body parts, types of health and types of disease. He placed the other four parts (diagnosis, knowledge of medicines and foods, prophylaxis and therapy) on the same level as cooking or blacksmithing. Al-Fārābī's views on medicine are based on a defense of Aristotelian teaching against Galen’s teaching. Al-Fārābī's aim here was to strictly separate philosophy from medicine, since, from al-Fārābī's point of view, the latter did not meet the high standards of philosophy and logic. Galen, on the other hand, viewed medicine as inseparable from philosophy. In his criticism of Galen , al-Fārābī rejects his assumption that there are several organs that control the body. According to al-Fārābī's analogy between the structure of the universe and the structure of the details, there can only be one ruling organ that regulates the body's circulation. For al-Fārābī, this organ corresponds to the heart, since the heart supplies the body with nutrients via the arteries. Likewise, the spiritual interaction with the body is brought about through the heart, because the heart, following Aristotle, is the seat of the soul, whereas the brain is irrelevant according to Aristotelian ideas.

With regard to medicine, al-Fārābī rejects the path of empirical knowledge in order to arrive at a new understanding of the body. He rejects the dissection of corpses with reference to the logic of the first and second analytics of the Organon Aristotle, like Galen, also argued that different nerve cords lead to the brain. Aristotle saw here a meaning that governed the five senses he postulated. However, this was not received by al-Fārābī.

cosmology

Al-Fārābī's system of the universe is firmly rooted in the intellectual doctrine of Neoplatonism , which at that time had already established itself in Islamic philosophy. An important precursor here was al-Kindī, although al-Fārābī's kinematic model as a synthesis of Aristotle, the Ptolemaic worldview and Neoplatonism, had no forerunners in Arabic or Greek history. The key point here is the geocentric view of the world based on the knowledge of ancient astronomy, which moves the earth into the center of the universe and makes the planets and celestial bodies orbit the earth. The celestial bodies move in spheres that interact with each other. For example, the planets of the solar system are each assigned to a sphere. Aristotle was of the opinion that the spheres were moved by movers, in Islamic philosophy the term mover was replaced by that of the intellect. Since Aristotle, God is the first motionless mover who sets all other spheres in motion.

Al-Fārābī's doctrine of the intellect is a variant of the Neo-Platonic doctrine of emanation , which proceeds from the outflow of the divine into the lower spheres. The intellect emerges from God, who is thought of as a pure spirit being, and through the self-knowledge of God a further sphere arises in a kind of mirroring process. Through the further outflow of the divine into lower spheres, the celestial sphere, which itself contains no stars, and the other spheres arise. This is followed by the sphere of the fixed stars, which al-Fārābī regards as fixed in their position in heaven. The spheres of the planets of the solar system descend, starting with Saturn, towards the earth, with the moon being assigned its own sphere. The moon represents the dividing line between heavenly and earthly world. Below the moon the elements (fire, water, etc.) can be found in their pure form. All of these spheres each correspond to an intellect and are hierarchically ordered according to their sublimity. The difference to Aristotle is that Aristotle assumes two "movers" per sphere, one for the star itself and one for the movement of the sphere, whereas al-Fārābī only assumes one intellect per sphere. Al-Fārābī's explanation of the movement of the individual spheres is unclear.

There are several possible models, which are either based on Aristotle with two movers per sphere or assume only one mover. Janos assumes that al-Fārābī starts from one intellect per sphere, which sets the movement of the sphere in motion through emanation. The circular movements of the individual spheres cause the creation of matter. The tenth intellect determines the design of the earth itself. It is to be equated with the active intellect of Aristotle, with which man is able to establish contact. What is new about al-Fārābī is that matter is seen as a necessary condition for realizing the intellect in the lower world. In contrast to al-Kindī, for example, matter is not regarded as something evil that has to be overcome. According to al-Fārābī, the idea of matter is already contained in God and thus cannot itself be evil, since God himself is understood as unreservedly good.

Al-Fārābī combines his cosmological teaching with the interpretation of religiously transmitted miracle events. He sees the cause of miracles in the world of the spheres. This causes even individual miracles, a person who has established contact with this world, a prophet, but can also use her powers for himself and work miracles.

Human thought and science

It is fundamentally possible for humans to establish contact with the tenth intellect, but al-Fārābī assumes that this is reserved for a few gifted people, the philosophers or the prophets, who are nevertheless considered an ideal for the rest of humanity to emulate. Al-Fārābī divides the human mind according to the intellect theory. From al-Kindī he takes over the potential intellect, which corresponds to the possibility of thinking. Al-Fārābī complements the current intellect, the thinker capable of abstraction and familiar with science, and the acquired intellect, which is able to recognize the existence of the heavenly intellects. Finally, the active intellect corresponds to the tenth cosmic intellect. This intellect also represents the possibility of human happiness. Al-Fārābī's views on science, like his other ideas about recourse to hierarchical elements, are pervaded by them.

Central authority for al-Fārābī in the field of philosophy is the teaching of Athenian philosophy with its founders and central figures Plato and Aristotle, whose doctrine for al-Fārābī is authoritative on all central questions. Al-Fārābī sees in Athenian philosophy the starting point of the philosophical movement, which for him always remains a movement. He considers a breakdown into schools with different doctrines to be inadmissible. In terms of philosophy and history, philosophy passed from the ancient Greeks to the Arabs according to al-Fārābī. Al-Fārābī's judgment on the individual subject areas of human knowledge and the possibility of gaining knowledge in these areas is also strongly influenced by Aristotle. Al-Fārābī develops its own theory of human "reflection". According to this, people agree to designate certain objects with a repeatedly used term. This is how human language arises. The person then begins to differentiate between poetry and prose, then makes a distinction between normal prose and rhetoric and also differentiates both from grammar. The grammar serves to establish a system of order in the language. In the further development the human being is able to develop mathematical and physical conclusions. Al-Fārābī regards the logic of philosophy, particularly Aristotle Organon, as the culmination of human thought. Here is the opportunity to prove a point of view.

For al-Fārābī, the category theory of the Organon represents the basis of human thought. The various syllogistic final forms of the Organon each correspond to a science for al-Fārābī. Each type of conclusion is assigned a certain level of truthfulness. The demonstrative end is that of philosophy, which enables man to recognize the world through his own understanding, the dialectical end of that of theology, legal theory and linguistics. Since this is only ever recognized by some cultures, it no longer corresponds to the high standards of philosophy. The rhetorical ending and the poetic ending added by al-Fārābī are no longer even scientific, but serve religion, which pursues the goal of using descriptive parables to bring truths closer to incomprehensible people, which would otherwise not be accessible to them due to their lack of understanding. With regard to the Islamic religion itself, al-Fārābī pleads in many places for a symbolic or allegorical interpretation of the Koran. So he sees z. B. the otherworldly sanctioning of this worldly behavior as a matter only concerning the spirit, since only the spirit is capable of feeling.

Al-Fārābī's model state

Based on Plato's Politeia , al-Fārābī designed his own utopian state model, al-madīna al-fadila, the ideal city. In contrast to Plato, this is not to be understood as a specific city, like the Greek polis, but rather a political unit comprising several such communities. In analogy to his cosmic principle of order, which God envisages as the ruler of the world, al-Fārābī's ideal state is supposed to be directed by a philosopher-king, who at the same time acts as a prophet in order to be able to convey known truths in the form of parables that would otherwise remain incomprehensible.

Al-Fārābī's treatise shows a clear departure from the orthodox Islam of his time. He does not see Islamic society as the only one capable of achieving the ideal state, but basically allows all peoples to do so. This goes hand in hand with his theory of prophecy, which sees in religious symbolism only parables for those who are incapable of knowing the world through philosophy. Real virtue is in principle possible regardless of religion. Since religious truths are not logically substantiated, they cannot claim the same level of truth for themselves as spiritual cognitions to which the ruler of the philosophers came due to his connection with the active intellect. Ultimately, religious or social norms serve to maintain social stability. But they must always be subject to the control of the philosopher and thus to the control of logic, since only this is able to recognize central truths, which in al-Fārābī z. B. are to be equated with the assumptions that happiness is the goal of life or mathematical truths, such as that 2> 1. Al-Fārābī's model state clearly borrows from Plato. So he also assigns tasks to each individual according to his abilities, but the most honorable task is assigned to the ruler, who must be knowledgeable and fair and in contact with the active intellect. Like Plato, the ruler of the philosophers must be trained in scientific knowledge, but must also have moral and personal qualities. Al-Fārābī also emphasizes that it is almost impossible to find such a person, so in case of doubt it is better to transfer rule to several people.

Al-Fārābī distinguishes between several “ideal types” of a state, with the state structure surrounding the individual having an essential function with regard to his future salvation. Since the happiness of al-Fārābī is tied to knowledge and the inhabitants of the ideal state live under a ruler who has access to divine truth and can convey it, the inhabitants of the ideal state have a greater chance of reaching paradise after their death. Al-Fārābī also comments on the immoral state. This is based to a large extent on the poor morality of the rulers. Its inhabitants are lost to bliss and are more likely to go to hell after their death. In the ignorant state, on the other hand, there is the possibility that souls dissolve after death, since the inhabitants of this state cannot be held responsible for their ignorance and it would therefore be unjust to punish them after death.

reception

In the history of science of Islam, al-Fārābī is seen as the “second teacher” after Aristotle . Along with al-Kindī, ar-Rāzi , Avicenna and al-Ghazali , al-Fārābī is one of the most important representatives of Islamic philosophy . He is one of the most outstanding and comprehensive thinkers of the 10th century and is considered the greatest theoretician in Arab-Persian music history. It was also thanks to him that Greek philosophy found its way to the Orient. His works have been consulted and discussed intensively over the centuries. His epistemological basic work Kitāb Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm (Book on the Classification of the Sciences) had a special effect, also in Hebrew and Latin translations of the 11th and 12th centuries . Moses ibn Tibbon from the translator family Ibn Tibbon translated some of his works into Hebrew. As in similar cases of great scholars, al-Fārābī was occasionally appropriated, e.g. B. concerns the attribution to one's own ethnic group.

Avicenna in particular also referred to him. Avicenna's cosmological model seems to be heavily influenced by al-Fārābī. Likewise, the metaphorical consideration of individual speeches in the Koran by Avicenna (e.g. the metaphor of the divine throne) seems to go back to al-Fārābī's "method" of interpreting the Koran. The Aristotelian organon achieved through Fārābī a dominant status in Islamic theology for centuries. But there are also more far-reaching reception processes of Farabian philosophy, e.g. B. in Shiite mysticism. The Brethren of Basra, influenced by Fārābī's intellect theory, seem to have connected it with a mystical striving for salvation. The direct school of al-Fārābīs consisted mainly of the Arab Christians Yaḥyā ibn ʿAdī, Abū Sulaimān as-Siǧistānī, Yūsuf al-ʿĀmirī and Abū Haiyan at-Tauhidī. The philosopher's critic, al-Ġazālī, included Fārābī in his condemnation of philosophy,

Fonts

Writings on music

-

Kitāb Iḥṣāʾ al-īqāʿāt (Book of Classification of Rhythms)

- Translated by E. Neubauer: The theory of Īqā , I: Translation of the Kitāb al-īqā'āt by Abū Nasr al-Fārābī ', in: Oriens 34 (1994), pp. 103-73.

-

Kitāb fi 'l-īqāʿāt (book on rhythms)

- Translated by E. Neubauer: The theory of Īqā , I: Translation of the Kitāb al-īqā'āt by Abū Nasr al-Fārābī ', in: Oriens 21-22 (1968–9), pp. 196–232.

- Kitāb Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm (Book on the division of the sciences)

-

Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr (The great book of music;كتاب الموسيقى الكبير)

- ed. GAM Khashaba, Cairo 1967

- Translated by R. d'Erlanger: La musique arabe , Vol. 1, Paris 1930, pp. 1-306 and Vol. 2 (1935), pp. 1-101.

Philosophical and theological writings

- Kitāb Iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm (Book of Classification of Sciences)

- A. González Palencia (ed.): Catálogo de las Ciencias (text edition, Latin and Spanish translation), Madrid: Imprenta y Editorial Maestre 2nd A. 1953.

- Franz Schupp : Al-Farabi: About the sciences. De scientiis . Based on the Latin translation by Gerhard von Cremona, Meiner, Hamburg 2005

- Mabādiʾ ārāʾ ahl al-madīna al-fāḍila

- Richard Walzer (editor and translator): Al-Farabi on the Perfect State, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1985.

- Cleophea Ferrari: The principles of the views of the residents of the excellent city , Stuttgart: Reclam 2009.

- Risala fi'l-ʿaql

- M. Bouyges (Ed.): Epistle on the Intellect, Beirut: Imprimerie Catholique 1938.

- Kitāb al-Ḥurūf

- M. Mahdi (Ed.): The Book of Letters, Beirut: Dar al-Mashriq 1969.

- FW Zimmermann: Al-Farabi's Commentary and Short Treatise on Aristotle's De Interpretatione , Oxford University Press, Oxford 1981.

literature

- EA Beichert: The Science of Music in Al-Fārābī , Regensburg 1931.

- Deborah L. Black: Al-Farabi , in: Seyyed Hossein Nasr , Oliver Leaman (Eds.): History of Islamic Philosophy. 3 volumes. Routledge History of World Philosophies 5/1, Part 1, Routledge, London, New York 1996, pp. 178-197.

- Black, Deborah L .; Muhsin, Mahdi; Sawa, George (1999). Fārābī. In Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Norbert Campagna: Alfarabi - thinker between Orient and Occident. An introduction to his political philosophy , Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-938880-36-4 .

- Majid Fakhry: A history of Islamic philosophy . Studies in Oriental culture 5, Columbia University Press, Longman, New York 1983 ( excerpts ), 6 A. 2004, ISBN 0-231-13221-2 , pp. 111-132 et passim.

- Hendrich, Geert (2005). Arabic-Islamic Philosophy Past and Present. New York: Campus.

- Henry George Farmer : al-Fārābī , in: The music in past and present , Vol. 1 (1952), p. 315f.

- Henry George Farmer: Al-Fārābī's Arabic-Latin Writings on Music , Glasgow 1934.

- M. Galston: Politics and Excellence . The Political Philosophy of Alfarabi, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 1990.

- Rafael Ramón Guerrero: Apuntes biográficos de al-Fârâbî según sus vidas árabes , in: Anaquel de Estudios Árabes 14 (2003), pp. 231-238.

- Dimitri Gutas ( Biography , pp. 208-213), DL Black, TA. Druart, G. Sawa, Muhsin Mahdi : Art. Fārābī , in: Ehsan Yarshater et al. (Eds.): Encyclopaedia Iranica , Vol. 9, New York 1999, pp. 208-229

- Farid Hafez : Islamic-Political Thinkers: An Introduction to the History of Islamic-Political Ideas. Peter Lang, Frankfurt 2014 ISBN 3-631-64335-7 pp. 43–54

- Damien Janos: Method, Structure and Development in al-Fārābī's Cosmology. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2012

- Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian art music: history, musical instruments, structure, execution, characteristics. 2nd revised and expanded edition, Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, pp. 96–99

- Muḥsin Mahdī: Alfarabi and the foundation of Islamic political philosophy , University of Chicago Press , Chicago 2010, ISBN 978-0-226-50187-1 .

- Hossein Nasr : Abū Naṣr Fārābī [Introduction] , in: Ders. / Mehdi Amin Razavi (Ed.): An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia , Vol. 1: From Zoroaster to Umar Khayyam , Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999 (reprinted by IB Tauris, in collaboration with the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London-New York 2008), pp. 134-136.

- Ian R. Netton: Al-Farabi and His School . Arabic Thought and Culture Series, Routledge, London and New York 1992.

- Joshua Parens: An Islamic Philosophy of Virtuous Religions . Introducing Alfarabi, State University of New York Press, Albany 2006.

- DM Randel: Al-Fārābī and the Role of Arabic Music Theory in the Latin Middle Ages , in: Journal of the American Musicological Association 29/2 (1976), pp. 173-88.

- David C. Reisman: Al-Fārābī and the philosophical curriculum , in: Peter Adamson / Richard C. Taylor (Eds.): The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, pp. 52-71.

- Ulrich Rudolph: Islamic Philosophy. From the beginning to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2008, 3rd edition 2013 ISBN 3-406-50852-9 pp. 29–36.

- William Montgomery Watt : Art. Al-Fārābī , in: Encyclopedia of Philosophy , 2. A. Vol. 1 (article identical to 1. A. of 1967), p. 115f.

- Khella, Karam (2006). Arabic and Islamic Philosophy and its Influence on European Thought. Hamburg: Theory and Practice Publishing House.

- Madkour, Ibrahim (1963). In Sharif, MM (ed.) A History of Muslim Philosophy I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Mubahat Turker-Kuyel: Al-Fârâbî as a Source of the History of Philosophy and of Its Definition .

- Rudolph, Ulrich (2004). Islamic Philosophy From the Beginning to the Present. Munich: CH Beck.

Web links

- Literature by and about Al-Fārābī in the catalog of the German National Library

Primary texts

- Digital copies from the University of Granada

- De Intellectu Et Intellecto (lat.)

- Kitāb iḥṣā 'al-'ulūm / Catálogo de las ciencias , Spanish translation by Ángel González Palencia, Madrid 1953.

- On the origin of the sciences , De ortu scientiarium, a medieval introductory text to the philosophical sciences, ed. Clemens Baeumker , Münster 1916. Digitized at archive.org and gallica.bnf.fr .

- The model state , ed. F. Dieterici , EJ Brill, Leiden 1900.

- State administration , Leiden 1904

- Alfārábī's philosophical treatises , trans. F. Dieterici , EJ Brill, Leiden 1892. Digitized at archive.org : Version 1 , Version 2 , at gallica.bnf.fr: Version 3

- Latin texts on music in the Thesaurus Musicarum Latinarum

- Kitāb al-Ḥurūf , e-text.

literature

- H. Bédoret SJ: Les premières traductions tolédanes de philosophie . OEuvres d'Alfarabi. In: Revue néo-scolastique de philosophie , 41/57 (1938), pp. 80–97.

- Ian R. Netton : al-Farabi . In: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (English)

- Wilfrid Hodges, Therese-Anne Druart: al-Farabi's Philosophy of Logic and Language. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- 'Ammar al-Talbi : Al-Farabi (English; PDF; 80 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ According to the scholar -biographer adh-Dhahabī , Siyar aʿlām an-nubalāʾ , Vol. 15, p. 416 (2nd edition. Beirut 1993), the full name isمحمد بن محمد بن طرخان بن أوزلغ التركي الفارابي, DMG Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ṭarḫān b. Auzlaġ at-Turkī al-Fārābī . In his al-ʿIbar fī ḫabar man ġabar (edited by Fuʾād Sayyid. Kuwait 1961), Volume 2, p. 251, he calls him adh-Dhahabī Abū Naṣr al-Fārābī, Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. Ṭarḫān at-Turkī. So also in the scholar's biography of aṣ-Ṣafadī : The biographical lexicon of Ṣalāḥaddīn Ḫalīl Ibn-Aibak aṣ-Ṣafadī , Stuttgart u. a. 1962, 106, in the text: Abū Naṣr at-Turkī al-Fārābī (line 7); so also al-Maqrīzī : al-muqaffā al-kabīr . Vol. 7, p. 147 (Ed. Muḥammad al-Yaʿlāwī. Beirut 1991) with the explanation: "ḫarḫān ... is a non-Arabic (foreign) name"; "Auzlaġ: is a Turkish name"; Carl Brockelmann : History of Arabic Literature . Volume 1. Brill, Leiden 1943, p. 232; see. also the information in footnote 2. The authenticity of the Nisbe at-Turkī is doubted by Gutas 1999, since it is the earliest evidence in Ibn Challikān : Wafayāt al-aʿyān , Volume 5, p. 153 (Ed. Iḥsān ʿAbbās. Beirut 1968) ; his portrayal was shaped by the endeavor to ascribe al-Fārābī to Turkish ethnicity, which is why he also awarded him this nisbe. The relevant passage in ibn Challikān is e.g. B. quoted and translated by Syed Ameer Ali : Spirit of Islâm , London 2nd edition 1922 (various reprints), p. 485f.

- ↑ Rudolf Jockel (ed.): Islamische Geisteswelt: From Mohammed to the present. Drei Lilien Verlag, Wiesbaden 1981, p. 141

- ↑ E.g. Fakhry 2004, 111; Schupp 2005, xi; Black 1996, 178; Watt 1967, 115; Farmer 1952; Netton 1992, 5; Shlomo Pines : Philosophy . In: PM Holt et al. (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 2B, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1970, pp. 780-823, here p. 794: “... a descendant of a Central Asian Turkish family”; Henri Laoust : Les schismes dans l'Islam , Paris 1965, p. 158: "... né dans le Turkestan, à Fārāb, et sans doute d'origine turque, bien que l'iranisme le revendique aussi ...".

- ↑ Gutas 1999; Reisman 2005, 53.

- ↑ Schupp 2005, pp. Xi.xvi.

- ↑ Ẓahīr ad-Dīn al-Bayhaqī: Tatimmat siwān al-ḥikma , ed. M. Shāfiʿ, Lahore 1932, 16ff. According to Abdiïlhak Adnan: Farabi , in: İslâm Ansiklopedisi , Istanbul 1945, Vol. 4, pp. 451–469, here 453, this could be a fictitious takeover from the biography of al-Mutanabbī . Gutas 1999 also considers this plausible.

- ↑ Madkour, p 450

- ↑ Jean During, Zia Mirabdolbaghi, Dariush Safvat: The Art of Persian Music . Translation from French and Persian by Manuchehr Anvar, Mage Publishers, Washington DC 1991, ISBN 0-934211-22-1 , p. 40.

- ↑ Hossein Nasr: Three Muslim Sages. Cambridge / Mass. 1964, p. 16

- ^ Nasser Kanani: Traditional Persian Art Music: History, Musical Instruments, Structure, Execution, Characteristics. 2nd revised and expanded edition, Gardoon Verlag, Berlin 2012, p. 98

- ↑ George (1999). FĀRĀBĪ v. Music In Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ , George (1999). FĀRĀBĪ v. Music In Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ George (1999). FĀRĀBĪ v. Music In Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ In the Age of Al-Farabi: Arabic Philosophy in the Fourth / tenth Century (2008)

- ^ Gotthard Strohmaier : Avicenna. Beck, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-41946-1 , p. 109.

- ↑ In the Age of Al-Farabi: Arabic Philosophy in the Fourth / tenth Century (2008)

- ↑ In the Age of Al-Farabi: Arabic Philosophy in the Fourth / tenth Century (2008)

- ↑ In the Age of Al-Farabi: Arabic Philosophy in the Fourth / tenth Century (2008)

- ↑ Janos, 2012, p. 369

- ↑ Janos, 2012, p. 23

- ↑ See also HA Davidson: Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes on Intellect: Their cosmologies, theories of the active intellect, and theories of human intellect. New York / Oxford 1992.

- ↑ Janos, 2012, p. 120

- ↑ Janos, 2012, p. 356

- ↑ Madkour, p. 456

- ↑ Rudolph, p. 32

- ↑ , p. 467

- ↑ Hendrich, pp. 70-1

- ↑ Hendrich, p. 35

- ↑ Clifford Edmund Bosworth notes: "Great personalities such as al-Fārābī, al-Biruni and ibn Sina were assigned to their own people by overly enthusiastic Turkish researchers". ( Barbarian Incursions: The Coming of the Turks into the Islamic World , in: DS Richards (ed.): Islamic Civilization, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1973, pp. 1–16, here p. 2: “[…] great figures [...] as al-Farabi, al-Biruni, and ibn Sina have been attached by over-enthusiastic Turkish scholars to their race. "). The Ottoman patriotic magazine Hürriyet, for example, writes in its opening article from 1868 that the Turks were a people in whose schools al-Fārābīs, Avicennas, al-Ġazālīs, Zamachsharis cultivated knowledge.

- ↑ Janos, pp. 362-3

- ↑ Madkour, p. 467

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | al-Fārābī |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | al-Fārābī, Abū Nasr Muhḥammad; Alpharabius (Latinized); Alfarabi; El Farati; Avenassar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Muslim scholar and philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 870 |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 950 |

| Place of death | Damascus |