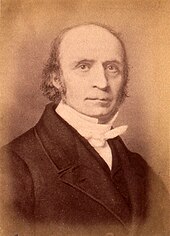

Franz Härter

Franz Härter (born August 1, 1797 in Strasbourg ; † August 5, 1874 in Strasbourg), with full name Franz Heinrich Härter , also known as François-Henri Haerter in French , was an Alsatian pastor.

Life

youth

Franz Heinrich Härter's father was a baker and confectioner and was called Franz Härter. His mother's maiden name was Luise Friederike Rhein. The father's business successes were moderate. This meant that the son had to support the father as an assistant after the death of his mother. Nevertheless, he was able to attend high school. Originally he wanted to study engineering afterwards.

Education

However, his father influenced him to the extent that he studied theology in his hometown from 1813 to 1819 in order to secure his pension. The course there was strongly shaped by rationalism . He was particularly influenced by Friedrich Karl Timotheus Emmerich (1786-1820), who taught him in ancient languages and encouraged him to read the Bible. On the same day that the son took the exam, the father who had previously been cared for by his son passed away.

In 1817 it was not possible to evangelically occupy the Strasbourg Citizens Hospital and place it under the supervision of Protestant Christians.

In 1820 Franz Heinrich Härter fell ill himself and went to Bad Hub for a cure. The bathroom was run by the Kampmann family based in Strasbourg. One daughter of this family was Henriette Elise (1799–1828), whom Härter met during his cure and who became engaged to her. Härter earned his living by teaching in Strasbourg, which was common for young theologians at the time.

In the same year, the Strasbourg magistrate, together with the pastors, was looking for two Protestant women to take over part of the nursing for the Protestant population. Since these were not found, the nursing of the sick was transferred exclusively to the Roman Catholic Vincentine Sisters. Härter discussed this with his pastor Kreiß. These events around the Bürger-Hospital in 1817 and 1820 were likely to be the first trigger that would later lead to Härter's establishment of the Strasbourg deaconess house.

In 1821, Härter toured northern France and Germany .

From autumn 1821 to early summer 1822 he was in Halle (Saale) . There he studied with Julius August Ludwig Wegscheider (1771–1849), whose theology was also rationalistic.

In the summer of 1822 he went to Jean Paul (1763-1825) in Bayreuth .

Franz Heinrich Härter was ordained in 1823. In the same year, the Alsatian branch of the Vincentian Sisters moved its headquarters from Zabern to Strasbourg. From there, the Vincentians opened up new fields of work in the following years and set up new branches in Alsace, south-west Germany and Austria .

Parish office in Ittenheim

In March 1823, Härter received his first pastor in Ittenheim . In the late summer of the same year he married Elise Kampmann. After the death of her mother, his wife took part in running the bathroom. Now she took care of the house and garden and looked after Franz Härter's grandmother. She also cared for other sick people in her husband's ward and gave handicraft lessons to young girls and women. Franz Härter tried to improve the schools and achieved that his church services were well attended, also took on medical tasks, tried to achieve a stricter, more spiritual morality in his congregation and ensured weak congregation members. His form of popular education combined elements of the Enlightenment and the revival movement . His role model was Johann Friedrich Oberlin (1740–1826), who had also proceeded in the Steintal valley, which Härter also visited several times. The pedagogical impulses that shaped Härter came from rationalism and also influenced the emerging movement of awakening.

His wife died of an infection on April 4, 1828, which affected Härter very much. She left behind two children, Sophie (1824–1869) and Gustav (1826–1903). This death plunged Härter into a ten-month crisis and also contributed to his turning more and more to the revival movement. In a funeral sermon that he wrote for himself, he confessed that he had rejected the core of the evangelical doctrine, namely the reconciliation through Christ's death on the cross, because he had considered this to be irrational. He now regretted this attitude, to which he had also led others, and after overcoming his life crisis he regarded himself as newly born.

Parish office in Strasbourg

In May 1829 Härter became the fourth pastor at the Lutheran New Church , the main Protestant church in Strasbourg.

Oberlin's influence had strengthened the revival movement in the city either directly or through people oriented towards him, also through family relationships. In the 1830s, numerous associations were founded in connection with the revival movement.

In March 1830, Härter married Friederike Dorothea Rausch (1799–1842), the daughter of a businessman and childhood friend of his late first wife. She gave birth to a son, who died shortly after birth, and the daughters Elise and Marie.

On Trinity 1831, that is, on May 29th, after a long hesitation in front of his congregation, he confessed to pietism by declaring that man would be redeemed only through Christ . He had thus publicly joined the revival movement, which he now supported in numerous associated associations. At that time the congregation tended towards rationalism, so that Härter's confession aroused opposition and the church leadership (consistory) took action against him. The strict Lutherans who opposed rationalism also rejected Härter. They bothered that he was teaching Bible studies. Furthermore, he lived and taught a practical Christianity that they were also suspicious of. Some colleagues and the theological faculty also disliked the turn of the most popular Strasbourg preacher towards pietism, which they rejected.

Harder was active in numerous clubs. From 1831 to 1839 he was on the board of the Neuhof-Anstalt, a school facility for both sexes that included elementary school, industrial school and agricultural school. The board also included Härter's friend, theology professor Karl Christian Leopold Cuvier (1798–1881).

Foundations

In 1834, Härter founded the Strasbourg Evangelical Society , also inspired by the Paris Evangelical Society. Cuvier was also involved here. In the same year, the so-called “Chapelle” was built as the central meeting room for the Strasbourg revival movement. It was a hall that was attached to a house in Rue de l'Ail that belonged to the Keck brothers.

In 1835, Härter helped found the Evangelical Mission Society in Strasbourg. He was also a member of the Society of Friends of Israel, which served the mission of the Jews, and worked in the administration of the Strasbourg Bible Society and the private poor institution.

On October 27, 1835, Theodor Fliedner wrote a letter to Franz Härter asking for a contribution to the Karlshulder sermon collection. At least since then, Fliedner Härter was known.

From Härter's pastoral work and from meetings with his confirmands, virgins and youth clubs developed. On May 11th, 1836, on his initiative, the “Virgins Association for the Promotion of the Kingdom of God our Savior” met for the first time. Its aim was to represent the cause of God among the people and to support those in need. A little later, Härter suggested the establishment of an association for poor women. The women serving the poor especially visited impoverished women, who were often older. The care of these widows and single people was previously inadequate. The voluntary work of the poor servants was initially carried out on Sundays, later, at their own request, also on weekdays.

The work of the poor women was not without criticism. They were accused of bringing people "nourishment for the souls from God's words", that is, they also dealt with biblical interpretation and missionary "soul care", as a circular from Härters to the servants of November 17, 1838 shows. But this was seen as a matter for the pastor. Härter vigorously rejected the criticism and encouraged the servants to continue their spiritual duties.

Development phase of the deaconess house

Härter had more concrete ideas for the form of a possible deaconess house after a visit to Kaiserswerth in 1839, where the first deaconess institute was founded on Theodor Fliedner's initiative.

On December 15, 1839, through prayer and the laying on of hands, he ordained ten women, previously called "servants", to be deaconesses . Given the success of the Vincentian Sisters with their seat in Strasbourg, Härter spoke of wanting to introduce "Evangelical Sisters of Mercy". This showed that in the early days he was more oriented towards the Roman Catholic Sisters of Mercy than the Kaiserswerther Diakonie.

From the beginning of 1842, efforts to found a Strasbourg deaconess house accelerated. In January, Härter noted in his diary that he had completed the first draft for such a facility. In February, Härter rented a small house (No. 5) on Rue du Ciel. The Administrative Committee met for the first time in March. Emma Passavant was entrusted with the administration as cashier, Henriette Rausch as supervisor for the school branch and Mina Ehrmann as secretary. To raise funds, Härter traveled to Upper Alsace and Switzerland .

In the spring of 1842, Härter visited Paris to collect money for the deaconess house and to get to know Pastor Vermeils' newly founded deaconess institution there. The costumes, seals and other details of the Strasbourg deaconess house were more like the Parisian than the Kaiserswerth model. This was shown by a correspondence between Franz Härters and Caroline Malvesin and the minutes of the administration of the Strasbourg deaconess house on November 10, 1842.

Härter adopted the rules for deaconesses from the Port Royal des Champs monastery . It was a Cistercian convent that had been founded in 1204 and gained in importance after reforms in the 17th century. During this time the poor and sick care as well as the educational work of the monastery had been intensified. The need to sanctify the individual nun was also emphasized. Franz Härter regarded Jean Duvergier de Hauranne , the abbot of St. Cyran, as a personal role model . He played a decisive role in shaping the monastery as a pastor. Härter thus followed the tradition of Jansenism . This Roman Catholic movement was fiercely opposed by the Jesuits from the middle of the 17th century, emphasizing the need for grace and rejecting purely work-based justice . Jansenism was thus closer to the Protestant faith with its basic principle of sola gratia than other Roman Catholic movements and could be considered as a model for Härter's work.

Furthermore, Härter often heard from Protestant women the desire to belong to a sisterhood based on the Roman Catholic model, up to and including the idea of converting. Wilhelmine Zimmermann wrote to him in her application for the new deaconess house on June 28, 1842: “I would like to go to a monastery.” Outwardly and with regard to the community aspect, the Roman Catholic role models were very attractive to Protestant women, like that Example of Amalie Sieveking had shown.

In terms of content and especially theological, Härter distinguished himself from these models. With this he defended himself against the accusation “the foundation of the deaconess work is a step backwards to the Roman church”, as he put it in his writing “About the difference between the sisterhood of deaconesses and a sisterhood of the Roman church”. So he judged that in the Roman Catholic sororities fairness to work, the externality of orders and meaningless obedience prevail without free development, while "in the Protestant Church faith causes voluntary obedience".

Strasbourg deaconess house

At the beginning of July 1842, the housemother and the first five sisters moved into the house. The deaconess house began to operate before it was officially founded. The sisters formed a provisional "inner council", which included the housemother, the teachers 'overseer and the nurses' head nurse. This council met for the first time on July 21.

The first patient was admitted on August 19. She suffered from nerve fever.

The influence of a Roman Catholic movement can be seen, for example, in the fact that Härter introduced the individual confessions of the deaconesses before the Lord's Supper, as a diary entry of the deaconess institution of September 3, 1842 shows.

The trial and training period for the first sisters was three months. At the end of September 1842, Härter blessed the first six sisters who then, at a meeting on September 29th, elected the deaconess Henriette Keck as head sister in a secret ballot. At this meeting the motto of the house was chosen, namely Phil 1,21 LUT : "Christ is my life, and death is my gain." Härter's numerous experiences with illness and death, which probably also contributed to his commitment to diakonia, were probably a reason for this selection.

On October 31, 1842, the day of the Reformation, after the organization had progressed enough, the foundation ceremony of the Strasbourg deaconess house took place in Himmelreichsgässchen, which ensured sick care in a large area and emerged from the parish diaconal youth work described above, in particular the parish-related poor servants' association. The date of the foundation made the evangelical character of the house clear, but is otherwise not associated with any special event in the continuous development of the facility. In addition to the six deaconesses in their traditional costumes, Härter, Professor Boegner, who interpreted the motto, and around 150 guests were present at the ceremony. The establishment of the Diakonissenhaus is considered to be Härter's greatest work, but at the time the foundation received little attention, only a short press release was found in the "Journal d´Alsace". The deaconess house is one of the foundations of the Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine .

Assessments

Härter is considered to be a pioneer in the development and implementation of parish diaconal concepts and in this also surpassed Theodor Fliedner. The fact that it was a form of diakonia that was created from the community for the community was particularly evident in Härter's two lectures on "The lay diaconate in the Protestant church in general and in the Protestant communities of Strasbourg in particular" (printed by Friedrich Carl Heitz) and on “The Office of Deaconesses in the Protestant Church, with a special relationship to the Deaconess Institution in Strasbourg” (printed by Berger-Levrault, Strasbourg 1842). The institute was founded only for training purposes and for social security for working and single women. Furthermore, Härter attached great importance to the community among the deaconesses. In his opinion, the sisters could complement each other with their different abilities, the elderly could pass on their experiences to the younger ones and the prayer community could support the individual and serve the "expansion of the kingdom of God".

Härter received suggestions for the foundation from various other institutions. He regarded the nursing services of the Sisters of Charity in the Strasbourg Citizens' Hospital as exemplary. Other role models were the Oberlins Toddler School and the Diakonie im Steintal. Härter also knew the Diakonissenanstalt in Kaiserswerth, which gave him important impulses for the design of the Strasbourg Deaconess House.

As a result, historiography in Germany generally did not perceive the Strasbourg institution as an independent project. Eduard von der Goltz judged that the beginnings were independent, but the permanent form arose from Fliedner's example. Arnd Götzelmann, on the other hand, showed in a more recent study the influence of Fliedner on Härter's foundation, but took the view that the importance of the Strasbourg house had been underestimated so far. Jutta Schmidt (see web links) also came to the conclusion that the influence from Kaiserswerth had so far been overestimated. If Härter himself pointed out this influence, Schmidt thought it was more of a justification. According to Schmidt, the Roman Catholic organizations and Oberlin were at least as influential for Härter.

The Diakonissenanstalt was near the border, in other words in the bilingual area. It belonged to France, a state with a Roman Catholic majority. Against this background, Härter emphasized the evangelical character of the institution. He rejected a split from the Lutheran Church or in a free church direction. The institute was, however, an independent Christian association and internal evangelical confessional differences played no role for Härter in practice.

Image of women and men

A special feature of the Diakonissenanstalt was the leadership by a female board. Theodor Schäfer called this a “female democracy”, Gerhard Uhlhorn a “real cooperative”. While Fliedner had placed his own office as head of the institution over the female offices of his institution and had given male bodies the main decision-making authority, Härter's institution was dominated by women. A purely female committee of the deaconess administration held the most important decision-making and management powers in the Strasbourg house, followed by the superior and then the leading sisters. But the sisterhood also had important say, for example in the choice of superiors and the admission of new sisters.

Härter, however, seemed to believe in a divinely willed division of tasks between man and woman: The seed-scattering man should "call out the sinful world from the sleep of death with enthusiastic speech", while the woman should tend and nourish the plants growing from the seeds. Particularly called women could fulfill this task in the diakonia. He compared their work with that of a missionary, also with regard to the organizational separation from the church. The man, on the other hand, works “more in general” in Härter's opinion.

tasks

The sketched picture of Härter's different tasks of the sexes corresponded to his own activity. He saw himself as a pioneer for the work of the deaconesses; the "care for the individual" is their business. He also considered it unnecessary to monitor the deaconesses' decisions in detail; he gave them full freedom of action and decision-making. Härter himself, like Vermeil in Paris, limited himself in the deaconess house to a function as pastor, theological advisor, teacher, confessor and administrator of the Lord's Supper; He did not want to exercise power in the institution. He had "a seat and vote, as often as he is appointed ... but he cannot introduce any changes in the existing order without the approval of the administration", as stated in a draft of the statutes of June 23, 1842. He attended all meetings of the internal council, but had no right of objection. He was also not considered the “father” of the house, the draft statutes only mentioned his religious activity as a “spiritual leader”, and his powers were officially kept small.

Härter's second wife died in autumn 1842, after which he remained unmarried. This also meant that his family had no influence on the deaconess institution that would not have met his expectations. From then on he rented a house and only ran a small household. Informally, however, he had a great influence on the house through his constant contact with the administration and the sisters and through his participation in the administration meetings. He was also in constant correspondence with the sisters who worked outside the home. All the sisters received Bible lessons from him, initially six hours a week.

The duties of the house were nursing and education. It initially had ten beds, ten nurses and a school for about 50 students.

further activities

In 1852, the facility also took over the “city maintenance” in the industrial city of Mulhouse in Upper Alsace. The care here was carried out by seven deaconesses. The project implemented the theoretical approaches that Härter had outlined in his lectures on the lay diaconate and the office of deaconesses mentioned above. The work done here in particular became a model in other communities.

In their early years, Härter gave several speeches in the Riehen Diakonissenanstalt . He carried out the idea of diakonia . In this way he shaped the diaconal understanding of the house. At the inauguration of this institution, he gave the ceremonial address on November 11, 1852. He pointed out the connection between prayer and diakonia: “The Diakonissen-Anstalt should become a standing article of your prayer, so that it can be a fountain from which a brook flows, through which infinite blessings can grow, yes, peace and true joy in heaven Mr. It is a delight to be able to pray and give. "

He gave another speech there at the annual festival of 1853 about the complete devotion of the deaconess to God: “If a soul decides to truly follow Christ and to serve the Lord in His work of salvation, then it must go according to the proverb: either entirely mine, or let it be! ”He was of the opinion that one can only really serve God and one's neighbor if one has given oneself completely to God beforehand. On other occasions, he expressed this with the terms humility and self-denial. But the reward of self-denial is life in abundance . (Compare Mt 10.39 LUT , Mt 16.25 LUT and Mk 8.35 LUT .)

Franz Härter's son Gustav, who was also a pastor in Strasbourg, also influenced the Riehener Anstalt, for example through his celebratory speech in 1854. Both mentioned the love of God, which precedes all human love, but emphasized the action of the deaconesses in the service of Christ.

It cannot be ruled out that individual deaconesses were thereby led to work righteousness and, contrary to evangelical teaching, assumed that they had to earn the love of God and people through their work. In general, however, the Protestant Church assumes that human love quickly reaches its limits if it is not preceded by the acceptance of God's love. This is likely to have been Pastor Respinger's motivation when he tried to counteract the tendencies mentioned at the annual celebration of 1855 by pointing out that one must first learn to serve with Jesus and be served by him if one wants to serve.

In 1859, the “city maintenance” in Mulhouse resulted in a nationwide community health care system.

Problems

Even after a deaconess married, strong bonds often remained with her fellow sisters and also with Franz Härter. This contributed to the fact that Härter's projects in Strasbourg were not undisputed during his lifetime.

The house struggled with a constant shortage of staff. Härter attributed this to opposition from the Strasbourg clergy. The few applicants were often of little education, which had to be compensated for by the training.

motto

Franz Härter's motto was Hebrews 13.8 LUT : "Jesus Christ yesterday and today and the same forever." In French, in the choice of words that can be found in the Louis Segond Bible , this verse is also on his tombstone in the deaconess cemetery in Königshofen (today in Strasbourg): "Jésus Christ est le même here, aujourd'huit et éternellement."

Works

Issued before 1840

- Stephen the Martyr: a sermon , Strasbourg 1832, printed by FC Heitz ( digitized version ).

- Give us today our daily bread: a sermon , Strasbourg 1834, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- The unknown with Jesus: a sermon given on the fourth Sunday of Advent 1834 , Strasbourg 1834, printed by FC Heitz ( digitized version ).

- Easter: a sermon delivered on Easter Sunday 1835 , Strasbourg 1835, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- The Last Judgment : A Contemplation for Christians in Search , Strasbourg 1835, printed by FC Heitz ( digitized version ).

- The Julius Celebration and the King's Festival: two speeches , Strasbourg 1836, print by FC Heitz ( digitized version ).

- The mysteries of the grave in the light of the resurrection of Jesus Christ: a sermon delivered on Easter Sunday 1836 , Strasbourg 1836, print by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- The parable of the Pharisee and tax collector : a sermon , Strasbourg 1836, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- Missionary sermon on the feast of the Holy Trinity, held May 29th 1836 , Strasbourg 1837, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- The right way of raising children: a school sermon given on the first Sunday after Easter , Strasbourg 1837, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- The Augsburg Confession : with a preliminary report, precisely compared texts and explanatory notes , Strasbourg 1838, Scheurer

- The self-humiliation: a sermon given on the 17th Sunday after Trinity , Strasbourg 1838, printed by FC Heitz ( digitized ).

- The Our Father , clarified in its application , Strasbourg 1839, pressure from FC Heitz ( digitized ).

- Sermon delivered on the Feast of Ascension in 1830 , Strasbourg 1839, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- I and my house want to serve the Lord , Strasbourg 1839, printed by FC Heitz ( digital version ).

Published 1840–1849

- The Sunday Celebration: A Contemplation on God's Commandment: "Remember the Sabbath day, that you keep it holy!" , Strasbourg 1840, printed by FC Heitz ( digital version ).

- The great joy: a sermon on Christmas 1840 , Strasbourg 1841, printed by FC Heitz ( digitized ).

- Following Christ: a sermon on Matt. 16, 21-26 , Strasbourg 1842, printed by FC Heitz ( digital version ).

- Enter through the narrow gate: a sermon on Matt. 7, 13-29 , Strasbourg 1843, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- God's goodness should guide us to repentance: two sermons , Strasbourg 1844, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized version ).

- The good advice for all who ask about eternal life: a sermon on Matt. 19, 16-26 , Strasbourg 1844, print by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- The glory of the Son of God: a sermon held in the Neu-Münsterkirche in Zurich on June 30th 1844 , Strasbourg 1844, printed by FC Heitz ( digital copy ).

- Sermons , multi-volume work, Strasbourg 1845, printed by FC Heitz and others

- The Sunday celebration according to divine and human rights: a sermon on Luke 14, 1-6 , Strasbourg 1845, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- The true confessor of Jesus Christ: a sermon on Matt. 10, 32 and 33 , Strasbourg 1846, print by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- The collection of the people of God: a sermon at Pentecost , Strasbourg 1847, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- The justification: a sermon , Strasbourg 1848, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

Published 1850-1859

- The divine prestige of the Bible: a lecture given at the annual Bible booklet in Strasbourg on November 1st, 1851 , Strasbourg 1852, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- Law and Gospel: a contemplation , Strasbourg 1855, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- The almost Christian and the complete Christian: sermon, delivered on the 24th Sunday after Trinity 1855 , Strasbourg 1855, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- Fear not, just believe !: A sermon , Strasbourg 1857, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- The blessed year: sermon at the harvest and autumn festivals 1857 , Strasbourg 1858, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- Speeches at the funeral of Mrs. Wittwe Keck: House mother of the Strasbourg Deaconess Work , Strasbourg 1859, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

Issued after 1859

- Joy in the service of the Lord: a speech given at the annual celebration of the Strasbourg Diakonissenanstalt in the New Church, on June 22, 1859 , Strasbourg 1860, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- The glorious freedom of the children of God: Sermon , Strasbourg 1860, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized ).

- Pauli's wish that we would all become resolute Christians: a sermon given on the 24th Sunday after Trinity 1861 , Strasbourg 1861, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

- The Lord's Sermon on the Mount and its application according to Matthew 7:12: a sermon , Strasbourg 1861, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digital copy ).

-

Handbook for young and old or Catechism of the Evangelicals. Doctrine of Salvation , Strasbourg 1862, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized version ).

- New edition: Nabu Press 2012, ISBN 1-274-47848-0

- This is what the enemy has done: Or the reformation of the sixteenth century against the apostasy of modern times; Official sermon given on the 23rd Sunday after Trinity 1863 , Strasbourg 1864, printed by Wwe Berger-Levrault

- Words spoken by ... F. Härter at the funeral of ... Jakob Matter, ... , Strasbourg 1864, printed by G. Silbermann

- The divine order of grace in a series of reflections , Strasbourg 1865, print by Wwe Berger-Levrault ( digitized version ).

- Farewell words to his community , Strasbourg 1874

Remembrance day

- August 5th in the Evangelical Name Calendar .

Honors

In the Neuhof district of Strasbourg, a street is named after François Haerter, as Franz Härter is called in French.

literature

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Härter, Franz. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 2, Bautz, Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-032-8 , Sp. 447-453.

- Charles Boegner: Au Service de Dieu. Souvenir du cinquantenaire de l'institution des diaconesses de Strasbourg , Imprimerie Strasbourgeoise, 1893.

- L. Roehrich: Le pasteur F.-H. Hærter , G. Fischbacher, Strasbourg and Paris 1889.

- René Frédéric Voeltzel: Service du Seigneur: la vie et les oeuvres du pasteur François Haerter: 1797–1874 , Strasbourg, Éditions Oberlin 1983.

- Bernard Vogler: Haerter, François Henri . In: Nouveau dictionnaire de biographie alsacienne , Faszikel 14, 1989, p. 1371.

- François-Georges Dreyfus , René Epp, Marc Lienhard (dir.): Catholiques, protestants, juifs en Alsace , Alsatia, Mulhouse, 1992, ISBN 2-7032-0199-0 , p. 132.

- Jean-Paul Haas: Strasbourg, rue du Ciel. L'établissement des Diaconesses de Strasbourg fête ses 150 ans d'existence européenne , Strasbourg, Éditions Oberlin, 1992, p. 26.

- Arnd Götzelmann: The Strasbourg Diakonissenanstalt - its relationships with the mother houses in Kaiserswerth and Paris. In: Udo Sträter (Ed.): Pietism and modern times . Volume 23. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-525-55895-3 , pp. 80-102 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- Jutta Schmidt: Occupation: Sister: Motherhouse diakonia in the 19th century . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-593-35984-7 , pp. 61-83 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- Doris Kellerhals, Lukrezia Seiler , Christine Stuber: Signs of Hope. Sister community on the way. 150 years of the Riehen deaconess house. Friedrich Reinhardt Verlag, Basel 2002, ISBN 3-7245-1208-2 , p. 202 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Inke Wegener: Between Courage And Humility: Female Diakonia Using Elise Averdieck's Example . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89971-121-1 , pp. 85–94 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

Web links

- Works by and about Franz Härter in the German Digital Library

- Franz Härter in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Franz Härter in the Ecumenical Name Calendar

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jutta Schmidt: Profession: Sister: Mother House Diakonie in the 19th Century , Campus Ffm New York 1998, About Franz Härter and his women's mission statement, pp. 61–81 ISBN 978-3-593-35984-7 . Table of contents: Profession sister

- ^ Diaconesses de Strasbourg, Vivre selon François Haerter aujourd'hui , Strasbourg, Éditions du Signe, 1997, 4ème de couverture.

- ↑ Heb 13: 8 in French Bible translations on Saintebible.com

- ^ Strasbourg street directory in French Wikipedia

- ↑ Maurice Moszberger (dir.): Dictionnaire historique des rues de Strasbourg , Le Verger, Barr, 2012 (nouvelle éd. Révisée), ISBN 9782845741393 , p. 388

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Harder, Franz |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Härter, Franz Heinrich; Härter, Franz H .; Härter, Franz; Härter, François; Härter, F .; Haerter, Franz Heinrich; Haerter, Franz; Haerter, François-Henri; Haerter, F. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French Protestant pastor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 1, 1797 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Strasbourg |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 5, 1874 |

| Place of death | Strasbourg |