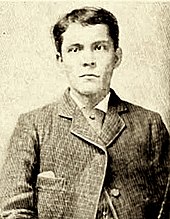

George Appo

George Washington Appo (born July 4, 1856 in New Haven , Connecticut , † May 17, 1930 in New York City ) was an American criminal of Chinese - Irish descent. After a "career" as a pickpocket , con artist and in drug trafficking as well as numerous prison sentences, he was the key witness of a commission of inquiry into police corruption in New York. After that, Appo, who continued to work as a criminal, was simultaneously supervised protégé and undercover investigator of the Society for the Prevention of Crime (SPC). Due to his public notoriety, he later played himself on Broadway . Impoverished and forgotten, he died at the age of 73.

Life

Origin and childhood

George Appo's father was Lee Ah Bow alias Quimbo Appo (approx. 1825-1912). He came from the Chinese province of Zhejiang , came to San Francisco in 1847 and was one of the first Chinese in this city. In 1849 Quimbo tried his hand at prospecting for gold and then went to the east coast of the United States , where he stayed in Boston , New York and New Haven and in 1854 married the Dublin- born Irishwoman Catherine Fitzpatrick. In 1856, a few weeks after the birth of their child George, the family moved to Manhattan in the Five Points slum , which was then ruled by feuding ethnic groups and controlled by the corrupt Tammany Hall . Quimbo worked there as a tea merchant.

In 1859, when George was not even three years old, his father got into a fight with his drunken wife, killed the landlady who had been added and injured two other residents. Quimbo Appo was initially sentenced to death. In a second trial, the sentence was reduced to ten years. When he was released early after four years, his wife had fled to California with George's little sister and died in a shipwreck. George had been left alone in New York.

After two more murders, numerous other acts of violence and several long prison sentences, Quimbo Appo had become the most famous Chinese in the city and was generally known as "Chinese Devil Man" and "Devil Appo". He eventually ended up in the madhouse Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane , where he died mentally deranged in 1912.

George Appo grew up without his family in the slum of Five Points. In Donovan's Lane, now defunct, called "Mördergasse", the shabbiest street in the Five Points, he stayed with a strange family for the next few years. "I wasn't raised, I was beaten," Appo later said. He never went to school. He acquired his limited reading and writing skills during later prison stays from fellow inmates.

Criminal "career"

As soon as he was able to do so, George Appo made a living as a newsboy. At an early age he joined a street gang with a friend, the Irishman George Dolan, and became active as a pickpocket. As Appo later described, pickpocketing was a kind of addiction to him. “If you're looking for a thrill, just try pulling the thick flap out of a man's inside pocket. It's unique - there the thing is already there and you have your fingers on it, but this brief moment in which it moves skillfully and safely in your direction, that is the moment in which there is such a mad feeling; Fire runs up and down your back. "

He drank from a very early age and became addicted to opium as a teenager . In addition to his thefts, he also earned extra income as a “tracer” (customer smuggler) of the Chinese opium dens in New York's Chinatown .

According to an Appo biographer, Appo must have acted quite skillfully as a pickpocket, because it took several years for his first arrest. In 1872 he was caught for the first time and admitted to a floating educational institution, the ship “Mercury”, where he experienced severe discipline, lax training and sexual assault. After 14 months he was released early for good conduct - he had saved a comrade from drowning. He immediately resumed his old job. In April 1874 he was arrested again for pickpocketing and this time sentenced to two and a half years of forced labor by the New York City Judge John K. Hackett . Since Appo was so small and skinny, a prison gown had to be made especially for him.

Released in April 1876, a month later he was followed and shot by a man from whom he had just stolen money. He only escaped arrest because a family friend hid him under the mattress of their bed. Eight months later he was caught stealing by a patrol officer. For this he was sentenced again to two and a half years of forced labor by Judge Henry A. Gildersleeve in January 1877 . He was serving that sentence in Clinton Prison , where he was mistreated by drunken guards. Appo suffered particularly from drug rehab while in prison. A prison doctor later described in detail how Appo's withdrawal attacked the whole organism and how his screaming kept the other prisoners awake.

In January 1879, 22-year-old Appo, as he himself described, was released as a "physical wreck" and "injured for life" and went public. In August 1880 he was arrested for seriously injuring a cardsharp with a knife in the stomach. He was charged with attempted murder, but the court found himself in self-defense and acquitted him. In March 1882 Appo was arrested again (the police officer shot himself in the hand) and in April sentenced by city magistrate Frederick Smyth to three and a half years for aggravated theft. Sent to Sing Sing Prison, the guards also mistreated him and knocked out his front teeth with a shovel. He then tried to commit suicide using tincture of opium . Meanwhile, a committee of inquiry into the conditions in the New York prisons was set up, to which Appo testified in early 1883. Then the worst grievances were remedied.

Appo used his last sentence to study. He also dealt with moral and religious questions for the first time. Dismissed in December 1884 for good conduct, Appo tried to hire a ship on a ship with a letter of recommendation from the “prisoner's aid”, then he worked briefly in a hat factory. According to his own account, however, he quit the job when he was falsely accused of theft.

Later he had to serve several prison terms, including eleven months for jewelry theft in Philadelphia , which he served in solitary confinement in Eastern State Penitentiary until 1887 , and in 1889 for pickpocketing in New York. He was once arrested in an opium den for illegally possessing weapons, but was able to evade detention by bribing the police detective.

A "good fella"

Speaking of the ideal of a person he aspired to throughout his life, was that of a “good fella” (“good fellow”), a “good guy”. Today this term, which arose in the criminal gang milieu, is equated with “Mafia gangster”. Appo, on the other hand, understood this term in its original meaning: that one is seen by his companions as clever, but also as trustworthy and generous. Appo himself described it like this: "In the eyes and in the opinion of the underworld, a 'good guy' is a brazen crook ('nervy crook'), someone who finds money and then spends it." A "good guy" was brave and discreet : “I have been attacked many times by would-be brutalists and have had to defend myself. And I never yelled for the police to take revenge in court, even if I got most of it in the fight, ”Appo later wrote. More than once he woke up in the hospital with his head bandaged, just took his things and left without denouncing anyone.

The historian and Appo biographer Timothy J. Gilfoyle describes him as a crook who used cunning and intelligence to make a living, but was generous to others. Contemporaries praised his soft and versatile voice, his pleasant pronunciation and his polite manners. When he was not under intoxicants, Appo was considered self-confident, but at the same time humble and helpful, even to strangers. When the doctor Harry H. Kane carried out one of the first scientific studies into drug abuse in New York, Appo served him as a contact person and helper in his research. A senior representative of the Society for the Prevention of Crime later described him as "loyal to the core" and one of the most fearless people he had ever seen.

It is noticeable that Appo only ever committed acts of violence under the influence of heavy alcohol. As a rule, he then emphasized during his interrogations that he could not remember his "freaking out".

In the “green stuff” shop

Through an acquaintance from the drug milieu, the 27-year-old Appo came into contact with a ring of commercial fraudsters in early 1884 and first learned the so-called flim flam game , a currency exchange trick known in German as the " vicissitudes ". He quickly expanded his skills to playing card games with dice and marked cards ("short carts").

In the drug milieu Appo also met a fraud group active in the "green stuff" business around the opium dealer Barney McGuire, for whom he initially worked. After he had retired from the business, he worked for the gang of Frederick Hadlick and then switched to the opium dealer and New York "king of the green business" James McNally . Appo had known McNally since the mid-1870s from the drug scene.

The “green stuff scam” was a combination of advance fraud and vicissitudes, closely related to the supposed money copier (“Romanian box”) known by Graf Lustig , and as widespread in the 19th century as the so-called “ Nigeria scam ” today . The cover story put forward by the fraudsters was the following: They claimed to be in possession of stolen printing plates from the American printing press and were therefore able to print duplicates of real dollar bills ("green stuff"). These alleged bills have now been offered for 10% of their market value by mailing wealthy provincials whose names the gang took from local address books. Once the buyer had paid with real money, an exchange trick was used to give them a box of worthless paper strips. The fraudsters assumed that the majority of those duped would not turn to the police.

Appo was very sober: “What chance do you have, in a strange place and in a strange game? Most are vain enough to shut up after being gutted. That is the whole philosophy of the business. Of course, some are just stupid. And they are easy prey. We have to scare the others. "

The “green stuff” gangs were tightly organized and proceeded according to a strict division of labor: the “backer”, also known as the “capitalist”, provided the sums of money necessary to carry out the fraud; the "writer" wrote and sent the letters used as bait; the "picker" or "decoy" ("Bunco Steerer") prepared the sale, brought the victim to a controlled location ("turning point") and monitored the business; the "Old Man", a harmless and dignified-looking person, was present as a distraction during the cheating; the "Wender" ("Turner") played the son of the "Old Man" and handled the business; the “fraudster” (“wrestler”) exchanged the money package at the right moment; and the "tailer", a type of thug, intervened in the event of problems, often in the role of a police officer.

According to a later report by a state commission of inquiry, the 35-strong gang around McNally sent between 10,000 and 15,000 letters a day in the early 1890s to attract victims. These letters were not written individually, but printed in large numbers. A newspaper tear was enclosed with them as a "receipt", also a fully printed forgery. Further contact then took place by telegram, with a number of post and telegraph employees working with the gang. Appo, who worked as a "steerer", received 10% of the fraudulent amount, but half of which was withheld as a bribe by McNally. He handled up to six “customers” every day. Appo used various aliases during these years, including George Leon and George Wilson. His buddies called him "Little George".

Appo wasted his money in night clubs and on drugs. He was repeatedly involved in fights and knife fights. With his partner and possibly his wife, Sarah Jane Miller (according to other sources Lena Miller), he lived so excessively that Miller was picked up on the street in July 1889 and had to be temporarily hospitalized because of mental disorders.

Shootout in Poughkeepsie

The "green stuff business" was not without its dangers. Appo had been stabbed once before by a provincial marshal posing as a customer. In December 1892 he was shot in the stomach and in early February 1893 he was stabbed by a knife in New Jersey .

On February 11, 1893, a hotel in the town of Poughkeepsie suffered a disaster for the now 36-year-old Appo. Two “customers” from the small town of Greenville , South Carolina , whom Appo was supposed to accompany from Poughkeepsie to New York, had become suspicious. One of them drew a revolver and shot him at close range. The bullet pierced his right eye and got stuck in his head. Appo was taken to the hospital, where he was initially accessible but could not remember that he had been shot. His eye could not be saved, the bullet was never removed.

All three involved were arrested and charged. Appo, who was bleeding profusely, was questioned the next day. He lied and asked for an opium pipe because of his pain. Just a week later, on February 18, he was brought to court with a half-bandaged face. His lawyer asked for the proceedings to be postponed because Appo's face was paralyzed and he was therefore unable to speak to his client. The request was rejected. At the beginning of March Appo was transferred from the hospital to pre-trial detention, where the prison guard took over the task of changing dressings.

Attempts by Appos accomplices to keep the two "customers" from making a statement failed. But the local police chief also failed when attempting to obtain documents about Appo from the corrupt New York police. The officers, bribed by McNally, said they didn't know Appo at all. At the end of March, McNally finally managed to get Appo out of custody on bail.

At the trial in April 1893, it wasn't the shooter who was convicted, but Appo. The grand jury , chaired by Judge Joseph Morchauser, imposed a prison sentence of 3 years and 2 months. When Appo, a drug addict, was about to be returned to Clinton Prison to serve his sentence in June 1893, he again attempted suicide with a potato knife from the prison kitchen. With the help of his “good fellows”, Appo went before the appeals court that same year , which overturned the judgment. He was released from custody after ten months.

Testimony before the investigative committee

Since his release from prison in 1893, Appo wanted to change his life. He slowly realized, as he wrote in his autobiography, “what a fool I was to take up the opium pipe again after being away from it for so long.” And he asked himself the question: “If I could do it so easily and I've managed to get away from opium so often, why not have the courage to break away from criminal life? ”In practice, however, the implementation of these resolutions turned out to be more difficult than expected and brought Appo into difficulties several times. All his attempts to give up drinking and smoking opium were unsuccessful.

In 1894, the Lexow Committee, named after New York Senator Clarence Lexow , began investigating corruption within the New York police force. The results of the commission of inquiry, published in 5 volumes in 1895, comprise more than 10,000 pages and contributed significantly to the defeat of Tammany Hall in the New York elections of 1894 and the election of reform mayor William Lafayette Strong .

One of the commission's main witnesses was George Appo, who was released from prison. Drug-free since entering prison, Appo behaved so unruly and nervous before his testimony that the investigators gave him his opium ration. In his testimony, Appo, who has meanwhile become gray-haired, provided a detailed description of the processes in the "green stuff business" and named places and people behind them. When asked about friends and “good fellows”, he refused to testify. Nor did he name a police officer, but did describe the protection the gang received by bribing the New York police.

Appo told investigators less than he knew, but the public reporting made his former cronies and corrupt police nervous. McNally set out on a trip to Europe in a rush. Therefore, Appo and the investigative authority expected acts of revenge. According to a newspaper report, bets were supposedly even accepted that he would not live to see the year 1895. As early as the end of June 1894 there were rumors that Appo had been abducted. In reality, Appo, who felt he was being persecuted by his old cronies, was being watched by agents of the investigative committee to protect him and keep him away from the opium for any further testimony.

In September 1894 Appo was attacked by a man whom he pursued to the elevated train station at City Hall . There a police officer let the man escape. At the end of September, Appo, bleeding from a neck wound, was taken to a New York police station. He looked badly drunk. Appo testified that he was drugged with knockout pills and that Mike Riordan, the bartender and brother of an alleged "green stuff man", tried to murder him. The police, on the other hand, assumed a suicide attempt and sent Appo to the detention center at Bellevue Hospital . The doctors first diagnosed delirium tremens and fixed him. On the other hand, John W. Goff , chief investigator of the Lexow Committee, stated that he believed that Appos' information was correct. Appo repeatedly refused to testify in court. A police officer - with numerous internal cases of drunk and brutality in office and at least three convictions - appeared who claimed Appo confessed to attempting suicide. Riordan was then acquitted.

In December 1894, Appo was knocked down once and twice attempted to abduct him.

Failed rehabilitation

According to his testimony, chief investigator Goff employed George Appo in the investigation department of the Lexow Committee, for which, among other things, he took on the not unproblematic task of delivering subpoenas. Appo later worked as an investigator for his long-time supervisor and friend Frank Moss of the Society for the Prevention of Crime (SPC) .

In the mid-1890s, Appo hit the New York stages. From December 1894 he played himself at the Broadway People's Theater in the gangster melodrama "In the Tenderloin ", a desolate story about the famous gangster Theodore "The" Davis. He had worked in the same trade as Appo and was shot in Texas in 1885 . Appo had been approached on the street by the play's author, Edmund E. Price, a gangster lawyer and former boxer. As a performer, he was quickly recognized by the audience and influenced his own image in public through his gangster roles. During the subsequent theater tour, Appo went to the local police authorities and asked that his picture be removed from the police investigation files because of his work for the committee and the SPC.

In April 1895, Appo was arrested in New York for "improper conduct" and "assault on a police officer". At the police station he met McNally, who had just returned from Europe, who abused and threatened him. Appo declared it to be a McNally-instigated conspiracy. He then toured Canada with the Derby Mascot Theater Company in violation of his bail conditions . After he attacked a man with a cane in a saloon in Toronto , he had to leave the city and returned with the troop to the United States. In August 1895, Appo was arrested again in Buffalo for the April incident in New York. In October he was sentenced to six months in prison.

After his release, Appo was no longer employed by the Society for the Prevention of Crime . As a result, he tried to make a living by lecturing on crime prevention and criminal law reform, but his efforts met with opposition from local authorities almost everywhere in the country.

In July 1896, Appo was arrested again for stabbing a reporter while he was drunk. When he attacked a second man, he was knocked down by him. Back in custody, Appo was examined in October 1896 for "acute mania " on his mental state, as there was a risk of injuring himself or others. The doctor diagnosed, among other things, tuberculous meningitis . In December 1896 Appo was insane without trial from custody to the prison madhouse Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane transferred, where he met his father Quimbo, who was detained as incurable there since 1878, and between a paranoid fear of Fenians and megalomania towards and staggered.

Only after two and a half years, in June 1899, was George Appo released as "cured". He was brought back to New York in handcuffs to be tried for the July 1896 knife attack. As a multiple offender, this time he was threatened with a life sentence. But the trial broke because the witness who brought the case could no longer be found. Appo was free.

Last years

From the turn of the century, things slowly fell silent around George Appo. Gradually his double-edged public reputation faded. A new committee of inquiry, the so-called Mazet Committee , is now investigating the political perpetrators of the corruption in Tammany Hall . While still in detention center, Appo said he was ready to testify before the investigative committee and could give names. But the Commission was not interested.

In October 1900, Appo was temporarily arrested again with a friend: The two had moved "in a questionable manner" in a crowd that was watching a large fire. The police apparently suspected Appo was again a pickpocket. In 1901 he finally accepted the position of assistant church servant at a New York congregation for a monthly salary of $ 15 and free accommodation, which at the time was about the income of an unskilled laborer. Appo received help from the socially committed general widow Rebecca Salome Foster, who campaigned for the rehabilitation of prisoners and was known as "Tombs' Angel" ("Angel of the Crypts"). She had already visited Appo in prison and brought him books. After his release he worked for Foster and in difficult cases took over the research in the "Milieu". When Rebecca Foster died in a hotel fire in 1902, Appo was among the mourners at the Calvary Episcopal Church and donated a dollar from his low salary so that a memorial could be erected to his benefactress.

Appo started giving lectures and interviews again, mostly on pickpocketing. He warned of the dangers, but at the same time described in glowing words the charm he had felt. In 1916, despite the lack of school education, Appo wrote an autobiography of almost a hundred pages without outside help . Preparatory work for this has been handed down from the 1890s, to which Appo was encouraged by Frank Moss. Due to his feeling for drama , speed and the narrative, Appo turned out to be a good writer, according to modern judgments, despite weaknesses in expression.

In 1912 the rumor arose that Appo had died in an asylum - a mistake made for his father Quimbo. In reality, Appo lived in a small apartment in New York's Hell's Kitchen neighborhood . In August 1929 he was admitted to Manhattan State Hospital , where he stayed for eight months. At this point, Appo was almost blind and deaf. Forgotten by the public, he died on Wards Island in May 1930 . Howard C. Baker, then head of the Society for the Prevention of Crime and Appo's only remaining friend, prevented him from being buried in a poor grave. George Appo's grave can still be found in Mount Hope Cemetery at Hastings-on-Hudson in Westchester County, New York .

reception

Migrant problem

The story of George Appo and his father Quimbo is a kind of parable for the early history of Chinese migration and the relationship between whites and Asians in America.

Quimbo Appo was considered one of the first Chinese in the USA and is often mentioned as the first Chinese in New York. The public initially regarded him as an “exemplary Chinese”. He spoke good English, was of Roman Catholic faith, was enterprising and was highly regarded by the Chinese community and authorities. Occasionally he even worked as a court interpreter. Marriage to an Irish woman was also not unusual among the Chinese at the time, as the Irish were also considered a marginalized group at the time. About a quarter of the women married to Chinese in New York were from Ireland. The phenomenon was marginal, as at the end of 1856 there were only about 150 Chinese in the city.

As the Chinese population grew, public attitudes changed and became hysterical. The Chinese now complained about the lack of willingness to integrate and spread racist prejudices, which were often justified biologically . As a New York daily newspaper described using the example of Quimbo Appo, which it describes as a “sickly, worthless Mongol”, the “clash of the unrestrained, barbaric nature of the East with the cooler way of life of our Saxon civilization”. This hostile attitude towards the Chinese population group culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prevented the immigration of Chinese (labor) migrants until 1943. From the 1880s there was no longer any newspaper report about George Appo that did not immediately refer to the ancestry of the "half-blood" and his "notorious" father.

Asian-European hybrids were also a new phenomenon in 19th century America. The New York Times , in a benevolent article on Quimbo Appo in 1856, described six-month-old George as "a beautiful, healthy child, very lively, and as white as his mother - a Yankee boy by all appearances ." But public opinion also changed with regard to these hybrids. In the context of an emerging “white Americanism”, mixed marriages were now perceived as “crossing racial boundaries”. As early as 1858 the magazine Yankey Notions argued against the result of Sino-Irish mixed marriages: "And now, Chang-Mike, run home and take Pat-Chow and Rooney-Sing with you." (See picture)

According to contemporary sources, George Appo had completely broken away from his Chinese roots. Only his drug use brought him into contact with the Chinese, for example with the only Chinese New York Deputy Sheriff Tom Lee, who ran a game club and an opium den at the same time. "Professionally", George Appo worked mostly with Irish and German-born criminals such as Barney Maguire, James McNally, Ike Vail and Bill Vosburgh. In his private life he was in a relationship with a white woman who was described as attractive.

The phenomenon was also treated literarily. Thomas S. Denisons stage play from 1895 "Patsy O'Wang" shows the story of a Chinese-Irish hybrid as a farce . George Appo's life, however, turned out to be a tragedy. While O'Wang managed to switch from one identity to another on stage, George Appo led a hybrid existence throughout his life and thus remained a suspiciously eyed outsider. "To be honest," wrote a New York journalist about Appo in 1898, "such a man would be better off dead."

Speaking of gangster jargon

The numerous queries from the members of the Lexow Committee show that in some cases they did not understand what Appo wanted to express in his broad street jargon. The shorthand notes show how hard the recorders tried to bring Appo's formulations into a legible and reasonably understandable form. In fact, the interrelated statements and texts by George Appo are one of the first written sources on New York gangster language. Examples are the use of “dese”, “dem” and “dose”, expressions like “youse guys” (“you guys”), “dead game sport” (“damn brave guy”), “chase yerself” (“slip down my back ”),“ wot t'hell ”(“ What the devil ”) and“ hully gee! ”(“ Holy Jesus! ”).

Appo describes in his jargon the everyday gangster life in which someone works as a “carbuzzer” (“train pickpocket”), first distracting the victim with “stalls” (“a push”) and then giving him his “leathers” or “poke” ( "Wallet") decreases; or is a pimp ("the sucker for her") and lives off the girls ("living off the shame of the girls"); by tapping a "customer" ("knock a guy"), "kicking up" him and then robbing him and eliminating him ("stealing a guy"). Where everything revolves around a bundle of banknotes ("roll" or "wad"), an expression that comes from the gambling milieu ("to shoot one's wad") and has the vulgar connotation of "cum". And where you are happy when you move from pickpocketing to “sure thing graft”, a “sure trickery” like fraud or card games, where the risk of arrest is not that great.

George Appos language and idioms, according to Luc Sante in his 1991 book "Low Life", can be found "word for word in all Warner Brothers B-movies of the 1930s". This is certainly an exaggeration in the order of magnitude intended by Sante, but Appo's information and written records have definitely found their way into common usage and slang lexicons.

Literary processing

As early as 1892, Appo was one of the main characters in a somewhat sentimental story from the New York World entitled "Jim Tells His Story", which appeared in several American newspapers and allegedly depicts a real-life drug scene in the early 1880s. Appo's life and statements were also processed in the melodrama “In the Tenderloin” (1894) and the tear-out “A Green Goods Man” (1895), then Appo's favorite piece.

In 1897 Frank Moss published a multi-volume account of New York under the title "The American Metropolis". One chapter is dedicated to George Appo. Moss knew Appo well through his work with the Society for the Prevention of Crime. The text is based on conversations with Appo, the minutes of the Lexow committee and an autobiographical text by Appo, for which Moss had paid him. The following year, 1898, the lurid book by journalist Louis J. Beck called "New York's Chinatown" appeared. The heading of the chapter concerning Appo ("Born for crime") shows the direction of this colporta script .

In 2006 Timothy J. Gilfoyle's presentation “A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York ". The work uses the life of George Appos to scientifically treat numerous societal and social problems in New York in the 19th century. Gilfoyle reproduces large parts of the autobiography written by Appo in 1916. It was precisely these parts that met with a great public response in the USA and led to the stories of George Appo and his father Quimbo coming back into public consciousness.

In 2013 Gilfoyle published George Appo's full autobiography with supporting documents.

Autobiography

- [George Appo]: The urban underworld in late nineteenth-century New York. The autobiography of George Appo with related documents. Ed. V. Timothy J. Gilfoyle. Boston, MA: Bedford / St. Martins, 2013 (The Bedford series in history and culture) ISBN 978-0-312-60762-3

literature

- Ronald H. Bayor, Timothy J. Meagher (Eds.): The New York Irish. Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8018-5764-3 .

- Louis J. Beck: New York's Chinatown. New York: Bohemia, 1898.

- Timothy J. Gilfoyle: A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York: WW Norton, 2006, ISBN 0-393-06190-6 .

- Robert G. Lee: Orientals. Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999, ISBN 1-56639-753-7 .

- [Lexow Committee]: Report and Proceedings of the Senate Committee Appointed to Investigate the Police Department of the City of New York. Vol. II. Albany: Lyon State Printer, 1895. ( digitized version )

- Frank Moss: The American Metropolis. From Knickerbocker Days to the Present Time. New York City Life in All Its Various Phases. Vol. 3. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1897. ( digitized )

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Timothy J. Gilfoyle: A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Article Chinaman in New York. In: New York Times v. December 26, 1856 ( PDF ), in which George Appo's name, date of birth and place of birth are mentioned.

- ↑ a b c d e f John Kuo Wei Tchen: Quimbo Appo's Fear of Fenians. In: Ronald H. Bayor, Timothy J. Meagher (Eds.): The New York Irish. Baltimore, London 1996, pp. 125-152.

- ↑ a b c The New York Times v. December 26, 1856 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b c Robert G. Lee: Orientals. Asian Americans in Popular Culture. Philadelphia 1999, pp. 81f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Frank Moss: George Appo, a Child of the Slums. In: Ders .: The American Metropolis. Vol. 3. New York 1897, pp. 118-141 (based on an autobiographical text by Appo) ( digitized version ).

- ↑ cf. George David Brown: The Opium Smokers of Donovan's Lane. In: Appletons' Journal 10 (1873), pp. 270-273.

- ↑ The New York Times v. October 8, 1894 ( PDF ).

- ↑ a b Timothy J. Gilfoyle: Street Rats and gutter snipes. Child Pickpockets and Street Culture in New York City, 1850-1900. In: Journal of Social History 37 (2004), pp. 853-862.

- ^ Cunning Wiles of the City Pickpocket. In: The St. Louis Republic v. August 9, 1903 ( PDF ) (German translation).

- ^ New York Evening Telegram v. March 31, 1882 ( PDF ).

- ^ A b c Louis J. Beck: George Appo - Born to Crime. In: Ders .: New York's Chinatown. New York 1898, pp. 250-261; St. Paul Daily Globe v. November 13, 1892.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Appos testimony of June 14, 1894, in: Report and Proceedings of the Senate Committee Appointed to Investigate the Police Department of the City of New York. Vol. II. Albany 1895, pp. 1621-1664 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ John Keteltas Hackett (1821–1879).

- ^ Henry Alger Gildersleeve (1840–1923), last judge on the Supreme Court of New York State.

- ↑ The Richmond Planet v. September 19, 1896.

- ^ New York Times v. August 6th ( PDF ), August 7th ( PDF ), August 8th ( PDF ) & September 4, 1880 ( PDF ); The Sun (New York) v. August 9, 1880 .

- ↑ Frederick Smyth (1834–1900), last judge at the Supreme Court of New York State.

- ^ William Grimes, 'A Pickpocket's Tale': A 'Good Fellow' at Play in the Fields of New York Crime (review). In: New York Times v. August 9, 2006; The Sun (New York) v. April 27, 1882 ; New York Times v. April 27, 1882 ( PDF ).

- ↑ s. a. New York Times v. February 17 & 24, 1883.

- ↑ a b Timothy J. Gilfoyle: A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York 2006, pp. 196f.

- ↑ a b Matthew Price: A 'Good Fellow' in Gotham - A Literate Gilded Age Thief. In: The New York Observer v. August 20, 2006 (German translation by user: Tvwatch ).

- ^ Quoted from William Grimes: 'A Pickpocket's Tale': A 'Good Fellow' at Play in the Fields of New York Crime (review). In: New York Times v. August 9, 2006 (German translation by user: Tvwatch ).

- ^ A b William Bryk: A Good Fellow and a Wise Guy (review). In: The New York Sun v. August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Harry H. Kane: Drugs that Enslave. The Opium, Morphine, Chloral and Hashish Habits. Philadelphia 1881; Ders .: Opium Smoking in America and China. New York 1882; Ders .: A Hashish House in New York. In: Harper's Magazine 1883, pp. 944-949.

- ↑ cit. in: Charles Tilly: Credit and Blame. Princeton NJ 2007, pp. 89f.

- ^ The Evening World (NY) v. September 29, 1894 ; The New York Tribune v. September 29, 1894 ; The New York Times v. July 12, 1896 ( PDF ).

- ^ A b c d William Thomas Stead: Satan's Invisible World Displayed. New York 1897, pp. 107-118; Arthur Griffiths: Mysteries of Police and Crime. Vol. 1. London a. loc. cit. [1898], pp. 276-280; John B. Costello: Swindling Exposed. Syracuse NY 1907, pp. 188-201.

- ↑ a b Timothy J. Gilfoyle: Opium Dens and Bohemia (Abridged from the book 'A Pickpocket's Tale'). In: History Magazine February / March 2008, pp. 39–43.

- ^ Marietta Daily Leader (OH) v. February 18, 1899 .

- ↑ The Brooklyn Eagle v. April 25, 1889 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; The Evening World (NY) v. July 22, 1889 ; The Sun (NY) v. July 22, 1889 ( PDF ), December 30, 1889 ( PDF ) & February 13, 1893 ( PDF ); The New York Daily Tribune v. February 14, 1893 ( PDF ).

- ^ The Sun (New York) v. July 22, 1889 ( PDF ); The Evening World (NY) v. July 22, 1889 ; The Evening Telegram (NY) September 29, 1894.

- ^ The New York Daily Tribune v. February 14, 1893 ; Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle v. April 21, 1893 ( PDF ), April 25, 1893 ( PDF1 & PDF2 ) & April 26, 1893; The Sun (NY) v. April 26, 1893 .

- ^ The Sun (NY) & The Evening World (NY) v. July 22, 1889.

- ^ The New York Daily Tribune v. February 14, 1893 .

- ^ The Sun (NY) v. February 13, 1893 ; The New York Daily Tribune v. February 14, 1893 ; The Syracuse Courier v. February 14, 1893.

- ^ The Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle v. February 18 ( PDF ) & March 2, 1893 ( PDF ).

- ↑ The New York Times v. March 20 ( PDF ) & March 29, 1893 ( PDF ); The Sun (NY) v. March 26, 1893 & March 28, 1893 .

- ↑ The New York Times v. June 21, 1893 ( PDF ).

- ↑ cit. n. Jonathan Yardley: How a child of the streets led a life of theft and swindle - before finally reforming. In: The Washington Post v. August 6, 2006 (German translation by user: Tvwatch ).

- ^ The New York Tribune v. February 14, 1893 ( PDF ); The Evening World (NY) v. September 29, 1894; The Richmond Planet v. September 19, 1896.

- ↑ Clarence Lexow (1852-1910), German-American lawyer and later senator.

- ↑ 1827-1900.

- ↑ The New York Times v. September 30, 1894 ( PDF ).

- ^ The New York Tribune v. September 29, 1894 .

- ^ The Auburn Citizen Advertiser (NY) v. October 1, 1931; The New York Times v. September 9, 1894 ( PDF ).

- ^ John William Goff (1848-1924), lawyer and politician.

- ^ The New York Tribune v. September 29, 1894 ; The Evening World (NY) v. September 29, 1894; The New York Times v. September 30, 1894.

- ^ The Evening World (NY) v. October 2, 1894; The Sun (NY) v. October 3, 1894 .

- ^ The Sun (NY) v. December 19, 1894 .

- ^ Frank Moss (1860–1920), lawyer, reformer and author.

- ↑ Brooklyn Daily Eagle v. December 11th, 1894 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Interlopers on stage. In: Metropolitan Magazine 1 (1895), p. 25; Timothy J. Gilfoyle: Staging the Criminal. In the Tenderloin, Freak Drama, and the Criminal Celebrity. In: Prospects 30 (2005), pp. 285-307.

- ^ The Stark County Democrat (OH) v. January 24, 1895.

- ^ The New York Evening Telegram v. April 9, 1895; The Sun (NY) v. April 13, 1895 .

- ↑ The New York Times v. April 17, 1895 ( PDF ); Buffalo Morning Express v. May 20, 1895; New York Times v. May 22, 1895 ( PDF ).

- ^ The Evening Times (Washington DC) v. August 7, 1895; The Brooklyn Daily Eagle v. August 8, 1895 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ The New York Times v. October 4, 1895 ( PDF ) & The Sun (NY) v. October 4, 1895 .

- ↑ The New York Times v. June 17, 1896 ( PDF ); The Monroe County Mail v. June 25, 1896.

- ^ The Sun (NY) v. July 11, 1896 ; The New York Times v. July 12, 1896 ( PDF ); The New York Tribune v. July 12, 1896.

- ^ The Sun (NY) v. October 8, 1896 ; Brooklyn Daily Eagle v. October 11, 1896 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Syracuse Evening Herald v. December 28, 1896.

- ^ The Morning Times (Washington DC) v. October 27, 1898; The New York Tribune v. June 15, 1899.

- ^ The Sun (NY) v. June 15, 1899; The New York Times v. June 17, 1899 ( PDF ).

- ^ The New York Tribune v. June 16, 1899 .

- ^ The New York Evening Post v. October 30, 1900.

- ^ Boston Daily Globe v. October 21, 1901; Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle v. October 23, 1901 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Dates of life: 1848–1902.

- ↑ that is, "Angels of New York Prisons"; s. Timothy J. Gilfoyle, "America's Greatest Criminal Barracks." The Tombs and the Experience of Criminal Justice in New York City, 1838-1897. In: Journal of Urban History 29 (2003), pp. 525-554.

- ↑ The New York Times v. March 2, 1902 ( PDF ).

- ↑ The New York Times v. February 26, 1902 ( PDF ); The New York Tribune v. May 21, 1902 .

- ↑ The St. Louis Republic v. August 9, 1903; The New York Evening Post v. August 8, 1908.

- ^ A b [George Appo]: The urban underworld in late nineteenth-century New York. The autobiography of George Appo with related documents. Ed. V. Timothy J. Gilfoyle. Boston, MA: Bedford / St. Martins, 2013 (The Bedford series in history and culture) .

- ^ New York World v. June 24, 1912; The North Tonawanda Evening News (NY) v. June 27, 1912 ( PDF ).

- ^ Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle v. May 23, 1930 ( PDF ); The Auburn Citizen Advertiser (NY) v. October 1, 1931.

- ↑ Timothy J. Gilfoyle: A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York 2006, pp. 315-324.

- ↑ George Appo in the Find a Grave database . Retrieved July 2, 2018. .

- ↑ The New York Times v. April 12, 1859.

- ↑ Andrew Hsiao: The Chinese Syndrome (review). In: The Village Voice v. November 2, 1999.

- ^ The New York Daily Tribune v. October 23, 1876.

- ↑ John Kuo Wei Tchen: New York's Chinatown before. Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776-1882. Baltimore 1999 pp. 290f.

- ^ Yankey Notions 7 (1858), No. 3, title page.

- ↑ The New York Times v. April 25th, 26th & May 3rd, 4th, 17th 1883 & December 8th, 1884.

- ^ Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle v. April 21, 1893; The Evening World (NY) v. September 29, 1894.

- ↑ Thomas Stewart Denison (1848–1911), editor, author and linguist.

- ↑ a b Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present. Vol. 7. o. O. [London] 1904, pp. 177, 280.

- ↑ cit. n.William Bryk: A Good Fellow and a Wise Guy (review). In: The New York Sun v. August 9, 2006.

- ↑ reprinted in: St. Paul Daily Globe v. November 13, 1892 .

- ^ Johnstown Daily Republican v. February 2, 1895.

- ↑ Timothy J. Gilfoyle: A Pickpocket's Tale. The Underworld of Nineteenth-Century New York. New York 2006.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Appo, George |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Appo, George Washington (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American criminal |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th July 1856 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New Haven , Connecticut |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 17, 1930 |

| Place of death | New York City |