Silkwormbird

| Silkwormbird | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Male silkwormbird ( Molothrus bonariensis ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Molothrus bonariensis | ||||||||||||

| ( Gmelin, JF , 1789) |

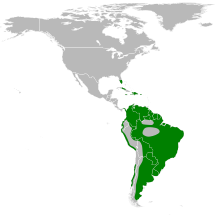

The Seidenkuhstärling ( Molothrus bonariensis ), sometimes also Glanzkuhstärling , is a small songbirds from the genus of Cowbird . The species, which is widespread in large parts of South America and the Caribbean , was first described scientifically in 1789 by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin . Like all representatives of its genus, the silkwormbird is a brood parasite that leaves the rearing of its own young to other species. Furthermore, it is a cultural follower that benefits from human changes in its habitat, such as the deforestation of forests.

features

Silkwormbird are rather small birds, their size depending on the subspecies between 18 ( M. b. Minimus ) and 22 cm ( M. b. Cabanisii ). Likewise, the weight varies considerably between the subspecies and can range from 31 to 65 g. The blackish-gray beak is conical in shape and of medium length. The relatively thin legs are similarly colored and end in long claws. The iris of the eye is dark brown or lead in color. The species has a significant sexual dimorphism . The plumage of the male is shiny black all over its body. It shimmers greenish blue on the wings and tail, while the rest of the body shines more in shades of purple, blue and purple. The females are much less conspicuous in color, their plumage shows olive-brown tones on the head and back, which sometimes merge into gray. On the torso and the contour feathers , the gray tones increasingly dominate, while the chest and stomach are kept in brown. The tail and wings show a darker, blackish brown.

The dimorphism of the species is already evident in almost all subspecies after the first complete moult , when the juvenile silkwormbird shed the uniform gray down of the nestling stage. Among all cowbirds, this is only the case with this species. While male juveniles can still be easily distinguished from adults , it can be difficult for females to separate them from adult specimens after the second moult.

Male silkwormbirds resemble a number of other songbirds with which they share their habitat, but almost all of these species lack pronounced sexual dimorphism. It can be particularly difficult to differentiate between silk- black cowbird and red-axed cowbird , whereby in addition to the song, the shape of the beak, the sheen of the plumage and the color of the iris can be used as separating features. In particular, due to the similar glossy effect of the plumage, it can also be confused with different Grackeln , but they are all significantly larger. Furthermore, the purple blackbird (rather greenish shiny plumage and lighter iris), the red-eyed cowbird (among other things larger, reddish iris) and the brown-headed cowbird (larger and bronze luster) are candidates for possible confusion.

behavior

The blackbird is an extremely social species that can form swarms of usually around 30, but sometimes up to 200 individuals for feeding and during rest phases. Resting places and rich feeding places are often shared with representatives of other starch species . Blackbird react aggressively to perceived threats, including people who get too close to the birds. Here they take a threatening posture with their beaks stretched vertically upwards and wings spread wide. Especially during the mating season, this behavior can also be observed in relation to representatives of the own species and the respective own gender. Apparently, this is a time-limited territorial behavior that cannot be observed outside of the breeding season. While foraging for food, the birds often cover several kilometers a day. Silkwormbirds - sometimes together with individuals of other species - actively attack birds of prey and try to chase them away if they get too close to a flock. The species is partially migratory : While populations native to tropical climates are considered to be resident birds , blackbird migrate from temperate areas to warmer regions during the winter months. Here, too, however, it can happen that individual individuals do not participate in the migration.

nutrition

Silkworms are not picky about their food sources and opportunistically accept almost anything edible they can find. Depending on the seasonal availability, arthropods and smaller seeds such as sorghum and millet millet represent a main component of the diet. As a culture successor, silk cowbird are also regularly sighted at artificial feeding places for birds or ingest rice grains, breadcrumbs or grain left by humans. The creation of feed depots is not known of the species. Some representatives of the species seem to have specialized in following cattle herds while grazing and eating frightened insects by them.

Vocalizations

The type is generally considered to be very vocal, the most frequently heard singing is described as a sequence of three to four deep, guttural sounds that are supposed to sound roughly like purr , followed by an ascending pe - tss - tseeee . Gender-specific chants also exist: while only males emit a clear, thin whistle in flight, females give a quick, repetitive chatter, especially when taking off. A short, harsh chuck is also used by both sexes as a contact call. This is also used in an even shorter form and repeated in quick succession during threatening gestures and arguments. Due to its melodic song, the silkybird was a popular pet for a long time , especially in the West Indies, and was kept in cages there.

Reproduction

Silkwormbirds do not form monogamous pairs; instead, the females are mated by several males during one breeding season. During courtship , the male birds try to win over potential partners by bowing on the ground, loud chants and conspicuous flight maneuvers. If copulation occurs, it only takes place once. After mating, the birds do not start building nests, as is customary with most species, instead they are brood parasites that rely on other species for the incubation of their eggs and the subsequent rearing of the young birds. Correspondingly, the development of a breeding spot in the female is missing , which is otherwise common in many species. The time of the breeding season is adapted to that of the selected host species. A large number of species can be used for this, with hosts that are slightly larger than silkwormbird and have similar eating habits tending to be preferred. Among the approximately 250 host species observed, the following species were parasitized most frequently: morning bunting ( Zonotrichia capensis ), blue - tipped bunting ( Diuca diuca ), fork-tailed king tyrant ( Tyrannus savana ), rust potter ( Funarius rufus ), white- banded mockingbird ( Mimus triurus ), brown potato ( Chrysomus ruficapillus ) and house wren ( Troglodytes aedon ). A host species preferred in one area can only play a subordinate role in another area despite its similar availability. The reasons for this selection are not conclusively known, but research suggests that individual females have a high level of specialization in a particular host. Female silkwormbirds use various methods to find suitable nests, including quietly and inconspicuously observing an area over a long period of time and actively shooing away birds that are busy building their nests. For this purpose, short flights are made through a possible nesting area with loud singing in order to be able to find the location of nests by flying birds. If an appropriate nest has been selected, it is usually flown to in the early morning hours before sunrise, but no later than noon. It seems to be irrelevant here whether the host birds have already laid their own eggs. While the eggs are being laid, the host birds are not necessarily absent, the whole process only takes about 30 seconds. It happens that the same nest is parasitized by several females, nests with more than 20, in extreme cases well over 30, blackbird eggs have already been observed. In order to increase their own breeding success, eggs found by the hosts are regularly punctured or pushed out of the nest.

The size and mass of the oval-shaped eggs depend on the subspecies, on average it is around 20 × 15 mm and around 4 g. There are also two color variations, in addition to a “flawless” white shape, there is also a much rarer “speckled” variant with bluish and brownish spots. If the eggs are successfully accepted and incubated, it takes about ten to eleven days for the young birds to hatch, which is shorter than the offspring of almost all preferred host species need. Immediately after hatching, the young are still naked and helpless, their average weight is 2.5 to 3.5 g. After four to five days, their eyes open, shortly afterwards mouse-gray down begins to form. During the nestling phase , silk cowbird show extremely aggressive and persistent begging behavior, with which they are often able to outdo the host's own offspring in competition for food. This behavior is not restricted to the “parents”, but is applied to everything that approaches the nest. After 12 to 14 days, the young fledglings and leave the nest, but also remain near the parents for a period of about three weeks and are provided with food by them. The young birds themselves reach sexual maturity after just one year.

A number of potential host species have adapted to the reproduction strategy of the blackbird in the course of time, in many cases the foreign offspring is recognized and not taken care of, which leads to death or ignores the eggs and does not incubate them. The success rate of the blackbird varies greatly with the hosts chosen, it is highest with Hispaniolatrupial with about 77%, while it is lowest with only about 7% with the morning hammer.

The parasitic breeding behavior of the blackbird was already observed and described in 1802 by the Spanish South American researcher Félix de Azara in Argentina and Paraguay. It is the oldest description of such behavior in a bird that does not belong to the cuckoo family .

Spread and endangerment

The blackbird is historically distributed on the South American continent, where the species inhabits almost all habitats. Only dense forests and areas over 2000 m altitude are generally avoided, with local evidence available up to 3500 m. Around 1900, the species began to gradually spread northward from Venezuela across the Caribbean, where it is found everywhere except on a few islands between Anguilla and Guadeloupe . At the moment the Bahamas and the south of Florida represent the northernmost extensions of the range, a further extension in the future is assumed. This development is mainly made possible by the increasing deforestation of the forests and the spread of agricultural land in the region, which create new suitable habitats for the blackbird. On the basis of this development, the IUCN lists the species as not endangered (status least concern ) and notes a sustained positive population development. In parts of its extended range, the species is considered invasive and threatens the continued existence of some songbird species that have not been affected by breeding parasitism in the past and have accordingly developed no or insufficient defense strategies against this behavior. Active measures are therefore being taken to control the blackbird populations on some Caribbean islands. In Puerto Rico, for example, the birds are hunted with traps and then killed. In the course of this, the population of the endemic and endangered yellow-shouldered blackbird was able to recover from just 300 to 800 animals. Since it eats human-produced grain, if available, the silkybird is regionally considered an agricultural pest and is controlled accordingly. The cowbird's natural predators include the great falcon , merline and gold dust mongoose .

Systematics

Johann Friedrich Gmelin described the species for the first time under the scientific name Tanagra bonariensis and initially placed it among the Schillertangaren . Investigations on mitochondrial DNA indicate that the individual species within the genus Molothrus form a monophyletic group. Furthermore, there are apparently particularly close relationships between the blackbird and the red-eyed cowbird ( M. aeneus ) and the brown-headed cowbird ( M. ater ). In addition to the nominate form M. b. bonariensis , six other subspecies are currently considered valid. These differ mainly in terms of their size and color, whereby the unambiguous identification of female individuals is usually easier, as they usually have more distinct differences in their color than the males. The geographical distribution of some subspecies partially overlaps.

- M. b. bonariensis ( Gmelin, JF , 1789) - Eastern and southern Brazil, eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina up to the level of the province of Chubut . Introduced in some regions of Chile.

- M. b. cabanisii Cassin , 1866 - Eastern Panama and tropical regions of Colombia, where there is overlap with M. b. bonariensis can come. This is the largest subspecies. Males resemble the nominate form, while females are generally paler in color.

- M. b. venezuelensis Stone , 1891 - Eastern Colombia, Northern Venezuela, Amazonia to Bolívar in Bolivia. Males have a more pronounced purple sheen on their plumage, while females are generally darker.

- M. b. occidentalis by Berlepsch & Stolzmann , 1892 - Western Peru and the extreme southwest of Ecuador. Males resemble M. b. venezuelensis , while females have paler upper surfaces, very pale and striped undersides, and dark streaks behind the eyes.

- M. b. minimus Dalmas , 1900 - Extreme northern Brazil and Guyana, Caribbean Islands and southernmost Florida. This is the smallest of the seven subspecies, the males of which closely resemble the nominate form. Females have a darker forehead and hood as well as striking stripes on the shoulder feathers.

- M. b. aequatorialis Chapman , 1915 - Southwestern Colombia and western Ecuador. One of the larger subspecies. Males shimmer more purple and less bluish, while females are generally darker in color and have no stripes behind the eyes.

- M. b. riparius Griscom & Greenway , 1937 - Eastern Peru and parts of Amazonia. Males correspond to the nominate form, while females are blacker on the top and paler on the underside.

Web links

- Recordings of vocalizations at xeno-canto.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Appearance. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 9, 2020 (English).

- ^ A b c Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Behavior. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 11, 2020 (English).

- ^ A b c Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Distribution. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 9, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Diet and Foraging. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 10, 2020 (English).

- ^ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Sounds and Vocal Behavior. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 11, 2020 (English).

- ^ A b Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Conservation. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 12, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Ricardo López-Ortiz, Eduardo A. Ventosa-Febles, Katsí R. Ramos-Álvarez, Roseanne Medina-Miranda, Alexander Cruz: Reduction in host use suggests host specificity in individual shiny cowbirds (Molothrus bonariensis) . In: Ornitologia Neotropical . tape 17 , 2006, p. 259-269 .

- ↑ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Breeding. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 13, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Demography and Populations. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 13, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Nick B. Davies: Cuckoos, Cowbirds and Other Cheats . T & AD Poyser, London 2000, ISBN 978-1-4081-3666-9 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Shiny Cowbird. In: BirdLife International. iucnredlist.org, 2018, accessed March 9, 2020 .

- ↑ Alexander Cruz, Ricardo López-Ortiz, Eduardo A. Ventosa-Febles, James W. Wiley, Tammie K. Nakamura, Katsi R. Ramos-Alvarez, William Post: Ecology and Management of Shiny Cowbirds (Molothrus bonariensis) and Endangered Yellow- Shouldered Blackbirds (Agelaius xanthomus) in Puerto Rico . In: Ornithological Monographs . tape 78 , no. 57 , 2005, p. 38-44 , doi : 10.2307 / 40166813 .

- ^ Molothrus bonariensis (Gmelin, 1789). In: gbif.org. Retrieved March 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Peter E. Lowther: Shiny Cowbird Molothrus bonariensis - Systematics. In: cornell.edu. TS Schulenburg, 2011, accessed on March 3, 2020 (English).