Marriage of Napoleon I to Marie-Louise

The marriage of Napoleon I. with Marie-Louise happened in the year 1810 to the succession problem in the French Empire to solve. At the same time, after the end of the Fifth Coalition War , the marriage connection was supposed to establish an alliance between the Empire of Austria and France.

prehistory

The Succession Problem

The childlessness in Napoléon's first marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais turned out to be increasingly problematic, because the conversion of the French consulate into a hereditary empire necessitated a male heir who could continue the Bonaparte dynasty . However, shortly before Napoléon's coronation, Joséphine was 41 years old, which is why Napoléon's circle of people called for a divorce and a new marriage. For her part, Joséphine used an opportunity presented to her to make a divorce more difficult for Napoléon: on the occasion of his coronation, he wanted to be anointed by Pope Pius VII . Joséphine confessed to the Pope, who was staying in Paris, that she was married to Napoléon without a church blessing. Since their civil marriage was not recognized by the Catholic Church, Pope Napoleon could threaten not to take part in the rite. Napoléon ran the risk of having to postpone the coronation in front of the diplomats who had traveled from all over Europe. On the evening of December 1, 1804 - the day before the coronation - Napoléon and Joséphine were married in a chapel of the Tullerienschloss . The act happened with the knowledge of the Pope, but was kept secret from the public. Since the canon law provided no possibility of a divorce, Joséphine seemed to have secured her position at Napoleon's side.

In other respects, too, Joséphine was initially able to live up to Napoléon's dynastic ambitions: while still at the consulate, she had managed to convince him to marry her daughter Hortense to his brother Louis . In this way, on October 11, 1802, a child was born with Napoléon Charles , whom Napoléon had declared, albeit unofficially, to be his successor and who wanted to adopt him when he came of age. Napoléon Charles connected Joséphine's family to the Napoléons, which should further stabilize their position. The early death of Napoléon Charles on May 5, 1807, however, nullified Joséphine's concept of a dynasty of its own. The problem of succession to the throne became topical again. At the imperial court again voices were heard advising the French emperor to divorce Joséphine. The former French Foreign Minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord and Police Minister Joseph Fouché particularly stood out here.

Napoleon, however, did not listen to this criticism as long as he still assumed that he was sterile himself. Despite his numerous extramarital affairs, for example with Madame Duchatel, Félicie Longroy and Carlotta Gazzani, he initially had no children to show. Joséphine, however, had two children from his first marriage. Even when one of Napoléon's lovers, Éléonore Denuelle , became pregnant, the latter questioned his paternity. He thought Joachim Murat was the real father. However, Léon Denuelle, born on December 15, 1806, showed great physical resemblances to Napoléon.

Divorce from Joséphine

The popular popularity of Joséphine and Napoléon's personal affection for her spoke against the decision for a divorce. On the other hand, the pregnancy of his Polish mistress Maria Walewska in 1809 had shown that he was capable of childbearing, i.e. that he could possibly father an heir to the throne . This time Napoleon also recognized his paternity. Finally, the attempted assassination attempt by Friedrich Stapß, which failed on October 12, 1809, showed him how threatened the French empire would be if he died. Only through a biological son who could succeed him to the throne did he believe that he could secure the permanent continuation of his empire. Nevertheless, Napoleon did not inform his wife about his divorce plans until more than a month after his return from Austria. For example, he had evaded her to Castle Fontainebleau on the pretext of going hunting . On November 30, 1809, he finally invited Joséphine to an evening dinner together in the Tullerienschloss. He then justified himself having to part with her in the interests of France. As a result, Joséphine is said to have fainted or at least pretended to be. Napoléon is said to have called his Castle Prefect François-Joseph de Bausset to carry Josephine into her castle apartment. On December 15, 1809 around 8:00 p.m. Napoléon and Joséphine announced their civil divorce in the official circle of the imperial family, high state dignitaries and officers, also in the Tullerienschloss. Under pressure from Napoléon, on January 9, 1810, the Paris diocesan authorities hastened to declare Napoléon's ecclesiastical marriage to Joséphine invalid.

Alliance political considerations for a new marriage

When looking for a new wife, only three candidates were shortlisted by the French emperor: a Saxon princess, a sister of the Russian tsar Alexander I and Marie-Louise , the daughter of the Austrian emperor. With such marriage connections, Napoléon, who owed his rise not to birth but only to military successes and political skill, wanted to finally integrate his ruling house into the ranks of the long-established dynasties of Europe. There were initially reservations about Marie-Louise due to the Austro-French War of 1809 . After the victory over Austria, Napoleon had even planned the dismemberment of the Habsburg monarchy . He had already had a decree prepared that allowed Hungary to gain independence. Urged by Talleyrand, Napoléon consented to talks with the Viennese court. Talleyrand intended an alliance with Austria, with the help of which he wanted to establish a stable balance of power politics in Europe. In this way, further campaigns that would overwhelm France's forces were to be prevented and a lasting peace order was to be established. By marrying Napoléon Bonaparte, Marie-Louise's father, Emperor Franz I , also hoped that the political situation would be strengthened. It was in Austria's interest to thwart a marriage between Napoleon and the Russian Princess Anna Pavlovna , as otherwise France in the west and the Tsarist Empire in the east threatened to embrace it. So Francis I reacted positively to a letter dated February 23, 1810, in which Napoleon asked for Marie-Louise's hand.

The positive attitude of the Austrian emperor was also related to the influence of a new important figure in Viennese politics: Klemens Wenzel Lothar von Metternich had taken the place of the previous Austrian Foreign Minister Johann Philipp von Stadion . Stadion had advocated the war of 1809 that Austria had lost and bet on a “no national survey” (according to the historian Wolfram Siemann ). In addition to working out a new foreign policy concept, Metternich was indirectly active as a moderator of the marriage. Napoléon turned to Metternich's wife Eleonore von Kaunitz at a masked ball in Paris , who forwarded the marriage request by letter to Metternich, who was in Vienna. He was one of the main proponents of the wedding, as it complied with his foreign policy concept of initially “nestling” Austria into the “triumphant French system” and “lifting its power for better times”. In the long term, Metternich saw Napoleon's impending marriage to Marie-Louise as a major tactical mistake: Due to the bad experiences in the Seven Years' War , the execution of Marie Antoinette and the harsh peace conditions of Schönbrunn, Austria was an ally that France could hardly win. Since the Peace of Tilsit , however, there was an alliance between Russia and France, which Napoléon now openly questioned with the marriage of Marie-Louise. With its decision against Anna Pavlovna, Russia and France continued unchecked towards a military escalation . In the event of a Russian-French war, on the other hand, Metternich saw the opportunity to retrospectively portray the marriage relationship as imposed by the victor: “Can one choose between the fall of an entire monarchy and the personal misfortune of a princess?” In this way Austria should secretly choose the option keep open an alliance change. At the same time, Metternich was entrusted by the Austrian Emperor with the task of convincing Archduchess Marie-Louise of the necessity of the wedding. Marie-Louise had to bow to the ideas of the dynasty here. She was not given any personal freedom of choice.

Diplomatic preparation and substitute wedding in Vienna

Official submission of the marriage proposal

Napoléon entrusted Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier with the official presentation of the marriage proposal. Berthier was an advocate of Austrian marriage and enjoyed Napoléon's full confidence. At the end of 1809 he had been appointed Prince of Wagram by the French Emperor . Berthier set out on February 22nd, 1810 and reached Vienna on March 4th, where he was hailed by the population as a bringer of peace. Three days later, Berthier appeared before Emperor Franz I. In his speech, he affirmed that France was seeking a reconciliation with Austria: “The policy of my sovereign [Napoleon] corresponds to the wishes of his heart. This union of two powerful families will give two generous nations new assurances of calm and happiness. ”Marie-Louise was then admitted to the audience. Berthier gave her a letter and a portrait of Napoléon. On March 9th, she signed a so-called renunciation document, which Napoléon was supposed to withdraw any right of inheritance to the Austrian throne.

Substitute wedding in Vienna

On March 11, 1810, a proxy wedding between the eighteen-year-old Archduchess and the Emperor of the French took place in the Augustinian Church in Vienna . This was not without problems, since Napoléon had recently divorced Joséphine and thus doubts arose about the ecclesiastical legal validity of the new marriage. In order to suppress such criticism, the Archbishop of Vienna pronounced his blessing on the wedding. The non-present Napoleon was represented by Archduke Karl , who had faced him as an opponent in the Franco-Austrian War of 1809. Napoléon himself had chosen him for this task in a letter of February 25, 1810, and sent Berthier to an audience with the Archduke on March 8, to emphasize his demand again. The Austrian Empress Maria Ludovika accompanied Marie-Louise to the altar, where “the Archduke procurator and Marie-Louise put rings on each other's fingers” (according to the court protocol on the following day). A total of twelve wedding rings were consecrated at the ceremony, as the finger strength of the French emperor was unknown at the Viennese court. The rings were sent on the trip to France and - as the protocol stipulated - should be handed over by Marie-Louise to Napoléon. At the end of the rite a choir sang the hymn "God, we praise you".

Marie-Louises travels to France

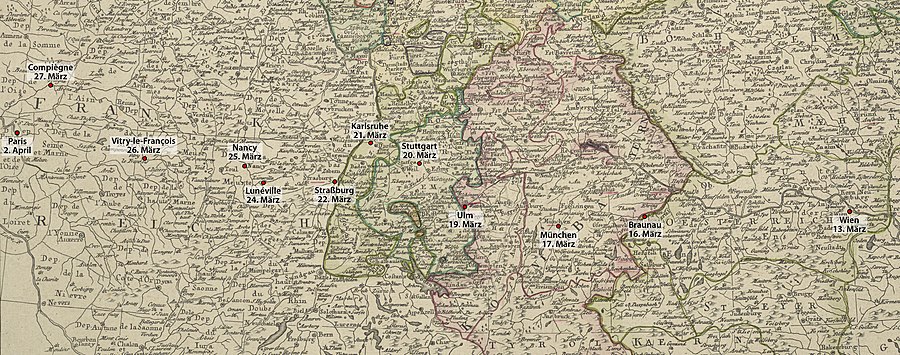

Departure from Vienna and handover ceremony in Braunau am Inn

The journey of the now French Empress Marie-Louise from Vienna to Paris required an elaborate courtly ceremony in which Napoléon wanted to tie in with the tradition of the Ancien Régime . He insisted on imitating Marie Antoinette's 1770 bridal voyage. This included, for example, holding a ceremonial handover ceremony on the border between the French and Austrian zones of influence and the couple's first meeting at Compiègne Castle . Marie-Louise said goodbye to her family on March 13, 1810 and left Vienna. She was accompanied by a court of 300 people. The convoy consisted of a total of 83 carriages pulled by 454 horses. On March 16, Marie-Louise entered the border between Austria and the Kingdom of Bavaria, allied with France, near Braunau am Inn . Marie-Louise's handover to France took place in a wooden pavilion built especially for the ceremony. The pavilion consisted of three rooms: an eastern hall represented Austria, a western France and the hall in between was intended as a neutral floor. There were also two entrances (one French and one Austrian). At 2 p.m. Marie-Louise walked through the Austrian hall and came to the neutral hall, where she was handed over to Berthier by the Austrian diplomat Ferdinand von Trauttmansdorff . Here Marie-Louise had to say goodbye to her Austrian court for good. After she was seated on a throne positioned in the hall, her new French court appeared. Her Austrian travel clothes were removed from her in the French hall. In a two-hour act, it was given a completely new French set. Marie-Louise was perfumed, newly dressed and given a new hairstyle, completing the symbolic change to the French empress.

Moving into Munich

On the evening of March 17, 1810, Marie-Louise and her entourage, consisting of 38 carriages, reached the Bavarian capital, Munich . The Wittelsbach dynasty residing there viewed the new marriage relationship with concern for two reasons: First, the eldest daughter of the Bavarian king was married to Eugène de Beauharnais , the son of Josèphine. With the divorce from Josèphine, Napoléon had devalued his dynastic connection to the Bavarian royal family. Second, Bavaria lost its geostrategic importance as a result of Napoléon's new marriage. Since the signing of the Bogenhausen Treaty , Bavaria had acted as a "bulwark" and a French deployment area towards neighboring Austria, for which Napoléon enlarged it territorially. In the course of the marriage to Marie-Louise, however, an agreement between Austria and France to the disadvantage of Bavaria seemed possible from now on. Last but not least, the uprising in the Bavarian Tyrol , which was only painstakingly suppressed , the anti-Napoleonic stance of the Bavarian prince to the throne Ludwig and the Bavarian blockade of a Confederation constitution all contributed to a tense relationship with France. As a result, the Bavarian government saw Marie-Louise's solemn entry into Munich as an opportunity to make Napoléon conciliatory: Crown Prince Ludwig had to accompany Marie-Louise von Haag to Munich. At the gates of the city, their convoy was received by five Bavarian units. When Marie-Louise's carriage reached the Alte Isarbrücke, the town's church bells began to ring at the same moment. In addition, guns fired gun salutes. Persistent heavy rain, however, hindered the urban illumination .

Marie-Louise's company did not consist entirely of French either. Metternich, for example, followed the convoy to Paris and was supposed to stay in the French capital for another 181 days. Given the requirement to look after Marie-Louise, he saw the opportunity to influence Napoléon personally in negotiations and thus to bring about a revision of the Schönbrunn peace treaty, which was tough for Austria (85 million francs in war compensation and an army limit of 150,000 men). Metternich had left Vienna on March 15, 1810 and caught up with the convoy in Strasbourg eight days later. He sent the Austrian emperor regular reports on the trip, behavior and sensitivities of Marie-Louise. Although Metternich was ultimately unable to mitigate the peace conditions, he did manage to sell the marriage as a success with which Austria secured years of recovery from the war.

Meeting at Compiègne

In order to keep the stresses and strains of the journey as low as possible, the route originally planned a stay in Soissons on March 27, 1810 . The place was the last stop before the planned meeting with Napoléon in Compiègne on the following day. The city of Soissons had already prepared to receive and accommodate the Empress. Napoleon did not do this quickly enough. He had already arrived in Compiègne on March 20, 1810, at around 7 p.m., and had personally arranged the final changes in the palace rooms of the Empress. On March 27, 1810, he decided to meet for a day. He rode incognito, accompanied only by his General Murat , towards Marie-Louise's convoy. At Courcelles-sur-Vesle , Napoléon finally found the entourage changing horses. He took the opportunity to get into Marie-Louise's carriage, disregarding all courtly conventions. He then let the carriages go through to Compiègne, where the couple arrived at 9:30 p.m.

Paris wedding

The official wedding took place on April 1, 1810 in the Louvre Chapel.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thierry Lentz : Le sacre de Napoléon, December 2, 1804 . Nouveau Monde Édition. Paris 2003, p. 132.

- ^ Thierry Lentz: Le Premier Empire. 1804-1815. Fayard, Paris 2018, pp. 502–504.

- ↑ Kate Williams: Joséphine. désir et ambition. Laffont, Paris 2013, p. 234.

- ^ Jean Tulard : Napoléon Les grands moments d'un destin. Paris 2006, p. 37.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Kate Williams: Joséphine. désir et ambition. Laffont. Paris 2013, pp. 334-335.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise. In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, p. 17.

- ↑ Jean Tulard: Napoleon or the Myth of the Savior. A biography. Wunderlich, Tübingen 1978, p. 404.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: Metternich statesman between restoration and modernity. Beck, Munich 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle . Réunion des Musées nationaux. Paris 2010. p. 18

- ^ Franz Wiltschek: Archduke Karl. The winner from Aspern. Styria, Graz 1983, p. 297.

- ^ Sigrid-Maria Großering: Shadows over Habsburg: with portraits based on contemporary paintings and photographs. Scheriau, Vienna 1991, p. 175.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Philip Dwyer: Citizen Emperor. Napoleon in Power 1799–1815 . Bloomsbury. London 2013. pp. 331-332.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Eberhard Weis : The establishment of the modern Bavarian state under King Max I. (1799-1825) In: Max Spindler (Hrsg.): Handbook of the Bavarian manual of Bavarian history. Vol. 4. Munich 1974. pp. 3-86, here, p. 37.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: Metternich statesman between restoration and modernity. Beck, Munich 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ Ch. Gastinel-Coural: Notes sur les décors textiles et les tapis des appartements de Marie-Louise pp. 115–126, here p. 117.

- ^ Jean Tulard: Diplomatic Games and the Dynastic Problem. The marriage of Napoleon and Marie-Louise In: 1810. The politics of love: Napoleon I and Marie-Louise in Compiegne, exhibition catalog of the National Museum in Compiegne Castle. Réunion des Musées nationaux, Paris 2010, p. 19.