Compiègne Castle

The Compiègne Castle ( French Château de Compiègne or Palais de Compiègne ) is a classicist castle complex in the French town of Compiègne in the Oise department in northern France. After Versailles and Fontainebleau, the extensive complex was the most important ruling residence in France, where the French kings traditionally stayed for a few days on the way to and from their coronation in Reims. The palace complex was on 24 October 1994 as a monument historique under monument protection provided.

From the 6th to 11th centuries, the predecessor buildings of today's complex were the preferred residence of the Merovingian and Carolingian kings. A new building for King Charles V was expanded and rebuilt in small steps by the French royal family until the middle of the 18th century, before Louis XV. commissioned a comprehensive change and expansion of the facility. Compiègne Castle was the only significant royal building in the second half of the 18th century. It was worked on for over 40 years. The name changed with the structural development: In the 17th century still called Louvre , in the 18th century the name gradually changed to Château ( German castle ) and in the Second Empire to Palais ( German palace ). At that time, under Napoleon III. and his wife Eugénie flourished again when they held court there during the so-called séries , a series of several week-long stays with cultural and social events. The couple used Compiègne as an autumn residence, where the court ceremonial was not as rigid as in the Tuileries Palace or in Saint Cloud . Empress Eugénie's heart was so attached to this castle that she later renamed part of her residence Farnborough Hill Compiègne in English exile .

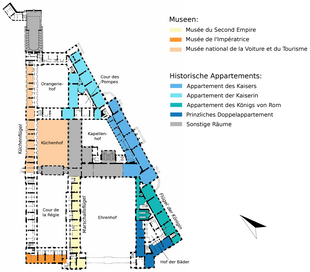

The historic apartments in the palace complex can now be viewed for a fee, including the princely double apartment and the apartment of the King of Rome as well as the apartments of the emperor and empress . They are the best-preserved Empire ensembles (both First and Second Empire ) in all of France. The complex also houses three different museums. The 20 hectare castle park is open to visitors every day. Entry is free there.

history

The beginnings and previous buildings

Compiègne was first mentioned as compendium villam in the Ten Books of Stories ( Decem libri historiarum ) written by Gregory of Tours in the 6th century . A first residence of the West Franconian kings in Compiègne is known through numerous documents. It may have come from the time of Clovis I and was probably made of wood. Chlothar I died in this villa regia in Compiègne in 561 . In the course of the 7th century the villa , which was mainly used as a hunting lodge, gained more and more importance and grew into a royal palatinate , which was named in the sources Compendium palatium . Dagobert I kept his royal treasure there, which his sons shared among themselves in 639. However, the location of this Palatinate, which was not a palace but more of a kind of country house, has not yet been localized. Under the Carolingians, Compiègne was a center of their rule and the diplomatic center of the western Franconian Empire . For example, the reception of an embassy from the Byzantine emperor Constantine V is documented for the year 757 .

On May 5, 877, Charles the Bald donated the Notre-Dame Abbey (later Saint-Corneille ) in Compiègne , the monastery church of which also served as a royal chapel . He also had a new royal residence built on the banks of the Oise , which was based on the model of the Aachen palatinate of his grandfather Charlemagne's and became his favorite residence . In 877 Ludwig II was crowned King of the West Franks in the monastery church. He died only two years later in Compiègne and was buried in the abbey. The same applies to the last Carolingian on the French throne: Ludwig V was also crowned in the monastery church in Compiègne and buried there after his death in 987. In 888 the coronation of Odos took place there.

At the beginning of the 10th century, parts of the castle and the monastery were destroyed in Norman raids. The damage left Karl III. fix in the following period. The abbey and the royal residence suffered renewed destruction due to a retaliatory strike by the Roman-German Emperor Otto II in 978. He had Compiègne attacked and set on fire after King Lothar had attacked Aachen in the summer of that year. After the death of Louis V, the Capetians ascended the French throne and remained loyal to Compiègne. Philipp August , who was baptized in the monastery church there, had the fortifications of the city expanded and reinforced and a round donjon built to control the bridge over the Oise. The ruins of this mighty round tower stand at today's rue de Jeanne d'Arc and are called the Beauregard Tower ( French tour de Beauregard ) or tour de Jeanne d'Arc . From 1300 onwards Philip the Fair held the Flemish Count Guido I captive in the donjon. Guido died there in 1305 because he refused to pay the enormous ransom.

After his coronation in Reims in November 1226, Louis the Saint made a stop in Compiègne, establishing a tradition that was continued for many centuries by the French monarchs . In Ludwig's time, the old Carolingian residence had already completely disappeared. It came into the possession of the Benedictines of Saint-Denis in 1150 , who replaced the previous congregation of Saint-Corneille and built a Hôtel-Dieu on the site . Ludwig had the Beauregard tower partially razed and put down and finally donated it to the Dominican Order in 1260 for the foundation of their own monastery. The kings only came to Compiègne more and more often to hunt and lived during their stays in a small hunting residence outside the city on the edge of the forest. The building called Royallieu had its own chapel, which was the cradle for a later abbey of the same name and gave its name to a current district of Compiègne. The hunting seat was a simple building and not big enough to hold large gatherings there, so Louis IX used it. for such purposes the Abbey of Saint-Corneille.

Medieval new building at the current location

Royallieu was not only too small for the king to hold court properly, but also too insecure because it was outside the protective city walls. Charles V therefore decided to build a new, larger residence in Compiègne. To this end, he bought a plot of land in the northeastern area of the city from the Abbey of Saint-Corneille in 1374 and gave the order not only to reinforce the city walls, but also to build a new building on the acquired land. This was not completely finished when Charles died in 1380 and stood where today's castle is. It was a complex, the four irregularly arranged wings of which enclosed an inner courtyard. The simple buildings took up roughly the space that is occupied today by the courtyard . In 1382 Charles's son Charles VI gathered . there the Estates General . In 1406 the wedding of Princess Isabella , widow of King Richard II of England , and her cousin Charles , who later became Duke of Orléans , took place in the royal residence . In the same year, the engagement of Isabella's younger brother Johann to Jakobäa von Bayern was celebrated there. During the clashes between the Bourguignons and the Armagnacs , the facility was badly damaged but rebuilt. It suffered the same fate in the Hundred Years War : within 16 years, the town and residence were conquered four times by English soldiers and just as often recaptured by French troops. This did not go hand in hand without damage.

By and large, the Louvre (from French l'œuvre , German: the work), called the residence, retained its medieval form until the 17th century . The French kings of the Renaissance added a few extensions, but these changed the appearance very little. For example, Francis I , who often came to Compiègne to hunt, had the main portal built at the time, including two flanking towers , and a ballroom built around the middle of what is now the cour de la Régie . Under Charles IX. The foundation stone for today's palace park was laid with the king's garden of around 6 hectares ( French jardin du Roi ) , but this king did not change the buildings either. Henry III. convened the Estates General again in Compiègne in 1576, after which the mostly unused royal residence gradually fell into disrepair and was soon no longer habitable. Heinrich IV therefore had some repairs carried out in 1598. Louis XIII banished his mother Maria de 'Medici from court in February 1631 after the Journée des dupes and placed her under house arrest in Compiègne, from where she managed to escape to Brussels on the evening of July 18. On the occasion of his last visit to Compiègne, Louis XIII. in October 1641 the order "to repair the castle and put it in good condition" ( "faire réparer le chasteau et le mettre en bon ordre" ). Presumably this order was carried out after his death under his widow Anna of Austria as guardian of the young Louis XIV , because from 1646 major renovations were carried out inside the residence, the work of which was intensified from 1650 and ended around 1655. During the Fronde fled Anne of Austria with her son and Cardinal Mazarin in Paris and moved from August 1652 Compiègne quarters. Mazarin also chose the residence as the place of marriage for his niece Laura Martinozzi to Alfonso IV d'Este , Duke of Modena , in May 1655.

Louis XIV came to Compiègne regularly during his reign to pursue his passion for hunting in the nearby forest. A total of 65 stays by the Sun King are recorded. From 1666, however, he not only stayed there for hunting, but also held the so-called camps of Compiègne ( French camps de Compiègne ), large-scale military exercises, in the vicinity of the city. One of these maneuvers took place from August 28 to September 22, 1698 and became almost legendary with the participation of around 60,000 soldiers. Along with the military operations, splendid festivals took place in Compiègne during the exercises. Despite his frequent stays, Louis XIV was not particularly fond of the place, but once said: “In Versailles I stay like a king, in Fontainebleau like a prince, in Compiègne like a peasant” ( French: “Je suis logé à Versailles en roi , à Fontainebleau en prince, à Compiègne en paysan ” ). He also had only marginal work carried out on the residence, which included the construction of a staircase of honor. Otherwise he limited the expenses for Compiègne to the cost of minor maintenance work, but numerous new houses and hotel particuliers were built in the city to accommodate the large court and the many political advisors during the camps of Compiègne . After the large military camp of 1698, the residence was unused for ten years and stood empty. Only in October 1708 did she see the Bavarian Elector Maximilian II Emanuel, a new resident who had to flee from the victors after the lost battle of Höchstädt . He found asylum in Compiègne in the Queen's former apartment for more than six years before the Peace of Baden allowed him to return to Bavaria in March 1715.

Redesign and extension to a classicist castle

The facility was idle for another 13 years before Louis XV in 1728 . first came to Compiègne. Like his grandfather, he was a passionate hunter, and because he liked it so much there, he hunted in Compiègne every year for one or two summer months. Ludwig's wife Maria Leszczyńska shared her husband's love for the complex, and it was also her preferred residence. The buildings, which were still medieval in essence, were completely unfashionable and uncomfortable, so Louis XV commissioned them. Robert de Cotte in 1729 with designs for a new building. De Cote's plans were for a castle with a floor plan in the shape of an St. Andrew's cross and thus resembling Stupinigi Castle in Turin , but the proposal was never implemented. Instead, Louis XV. From 1733 onwards to undertake some renovations inside the existing complex under the leadership of Nicholas d'Orbay and gave de Cote's successor as the king's first architect ( French premier architecte du Roi ), Jacques V. Gabriel , the order to create a second design for submit a new building. Gabriel planned a large, new castle outside the city on the edge of the forest, the construction of which was estimated at around four million livres . It seems that this exorbitant sum was too high for the king, and he rejected the plan in 1740 for reasons of cost.

While Gabriel was still working on the drafts for a completely new building, extensions to the existing residence began in 1736, which were also based on his plans. Once again, Nicholas d'Orbay was responsible for the construction supervision of the 2000 workers. The buildings around the orangery courtyard (including a new ballroom to the north) and the wing of the building where the ball gallery is located today were built by 1740 . The king's apartment was also enlarged. The cost of these measures was 300,000 livres. With a further 1.2 million livres, the new buildings for Ludwig's minister and the administrative staff near the palace once again made a difference. 1738 also began with the construction of the large horse stables ( French grands écuries ) south of the residence. Nevertheless, the complex remained too small to allow adequate court keeping, which is why the king had various proposals drawn up again after 1740 to finally put an end to the lack of space in Compiègne, but not one of them was implemented. The residence was initially further changed in small steps as required. In 1745 the king gave the order for a further extension to create two new apartments, which were intended for his son, the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand , and his first wife Maria Theresia Rafaela of Spain . Work on this was finished in 1747. It was not until October 1751 that the king took a liking to a design by Ange-Jacques Gabriel , who had replaced his father Jacques V as the king's first architect after his death in 1742. The project in the classicist Baroque style was essentially based on the triangular floor plan of the existing late medieval complex. Work on implementing the plan began in November of the same year. However, they progressed only very slowly because the castle was still used for the frequent royal hunting parties and these stays could not be impaired by the construction work. By 1755, the first half of today's Marshal's wing was built as an apartment for Ludwig's daughters, the garden facade of the Dauphin's apartment and his second wife Maria Josepha von Sachsen was completed, and a wing in the orangery courtyard was added one floor to an apartment for Ludwig's mistress Madame de Set up pompadour . With the outbreak of the Seven Years' War , the renovation slowed down and came to a complete standstill in 1757. Construction work was only resumed after the end of the war in 1763 and one of the two pavilions on the south side of the palace was completed. By 1770 the western part of the south wing at today's Place d'Armes was completed . That year, Louis XV arranged on May 14th the first meeting of the French heir to the throne Louis XVI. with his newly wed Austrian bride Marie Antoinette in the castle.

When the king died in 1774, the renovation and expansion work in Compiègne was far from complete. Louis XVI let the work begun under his grandfather continue according to the original plans, even when Ange-Jacques Gabriel gave up his post in 1775 for health reasons. For a long time, Jérôme Charles Bellicard , an employee of the Bâtiments du Roi , had been in charge of the construction site for a long time and had already filled this position a few years before Gabriel's departure. In 1776 he was replaced by Gabriel's student and partner Louis Le Dreux de la Châtre . He continued the work taking into account the plans of his teacher and added corresponding details so that Compiègne Castle, despite its rococo origin, looks sober from the outside and the interiors are furnished in the Louis quinze style instead of the Louis seize style were. By 1780, a new wing was built south of the king's apartment with a view of the garden, the interior of which was completed in 1784. Marie Antoinette chose this as a new domicile, which is why it was hereinafter referred to as the Queen's wing ( French aile de la Reine ). At the same time, the south-east wing of the main courtyard was redesigned and connected to the Queen's wing by a third wing with a pavilion. By August 1783, the rooms of the king's apartment were also completely redesigned. At the same time, this was expanded to include various rooms. For this purpose, the wing of the building on the northeast side of the so-called Royal Court ( French cour royale , today called Ehrenhof ) was completely redesigned between 1781 and 1785 and the rooms on the first floor were added to the royal apartment. In October 1783, work began on laying down the wing that had bounded the royal court on the west side up to that time. Its demolition resulted in today's court of honor , which was closed in 1785 on the southwest side by a double colonnade . The last major construction project finally began in 1785 with the construction of the so-called kitchen wing ( French: aile des Cuisines ) on the north-west side of the complex, which was to accommodate all of the castle's utility rooms in addition to the kitchen. Its shell was completed the following year. The most important construction work of the redesign was completed by 1788. The interior work, decoration work and furnishing continued until 1792. In his drafts, Ange-Jacques Gabriel had also planned the construction of a new chapel and the redesign of the square to the south of the palace, but these plans were never implemented. The creation of the French garden he planned also remained in its infancy due to financial difficulties.

First Republic and Napoleonic Period

Louis XVI intended to make Compiègne his main residence. The French crown jewels had already been brought into the castle, but the outbreak of the French Revolution thwarted the king's plans. In August 1792 the power of disposal over the castle was withdrawn and transferred to the Ministry of the Interior. In contrast to many other royal residences, the complex survived the turmoil of the revolutionary years completely unscathed. When it was planned in 1798 to celebrate the “Feast of the People's Sovereignty” ( French fête de la souveraineté du peuple ) in the castle , the organizers found that the palace was unsuitable because the Fleur-de-Lys , the Symbol of the French monarchy. From 1793 to 1794 the sick and injured of the Northern Army were housed in the castle, after which the furniture was completely sold from May 20 to September 13, 1795. The works of art were also supposed to be removed and brought to the Louvre , but that never happened. From August 18 to December 5, 1798, part of the castle was used as barracks for the First Volunteer Battalion from the Seine-et-Oise department . After the soldiers had cleared the building again, a military school ( French prytanée militaire ) was set up there in 1799 , which was converted into a college ( French école des arts et métiers ) on February 25, 1803 .

With the proclamation of the First Empire , the castle was included in the imperial domain ( French domaine impérial ) and was thus at the personal disposal of Napoleon . At the request of his wife Joséphine de Beauharnais , the emperor appointed Louis Martin Berthault , who had previously worked at Malmaison Castle , on August 25, 1806 as the architect of Compiègne Castle. Under the supervision of Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine , he was to change the complex into an imperial residence that corresponded to the taste of the time and was appropriate to the high position of its new owner. For this purpose, the university located in the building first had to move out and was relocated to Châlons-sur-Marne (today Châlons-en-Champagne ) on December 8, 1806 . On April 12, 1807, Napoleon approved a budget of 400,000 francs for the upcoming changes in Compiègne . In November of the same year Berthault presented the design for a ballroom , the ball gallery , which had not existed until then . With the consent of the emperor, the previous apartments of the Count and Countess von Artois , spread over two floors, were removed and construction of the new hall began at the end of 1809 . Its shell was completed in March of the following year. Berthault called on the brothers Étienne and Jacques-Louis Dubois, with whom he had previously worked in Malmaison, to redesign and redesign all of the interior spaces. He also hired the painters Pierre-Joseph Redouté and Anne Louis Girodet for ceiling and wall decorations . They had their hands full right from the start, because the Queen's former apartment and the apartments of Marie Antoinette's children were to be redesigned within a very short time to accommodate the former Spanish King Charles IV and his family from June 1808 to be able to accommodate. Napoleon had offered the deposed monarch Compiègne as a residence. The ex-king moved to the south of France just three months later in September. Only his daughter Maria Luisa , widow of the King of Etruria , who died in 1803 , stayed in Compiègne until April 4, 1809.

After the departure of Charles IV, the parts of the palace in which he lived were once again completely redesigned in order to set up an apartment for the accommodation of foreign rulers. According to Napoleon's will, the most splendidly furnished room sequence of the house ( “le plus sompteuse meublé de la maison” ) was to be set up there. As early as the spring of 1807, the king's former apartment was redesigned. Napoleon had chosen this as a symbolic new domicile and was henceforth called the emperor's apartment . The suite of rooms to the north was to become the Joséphine's apartment and was therefore given the name of the Empress's apartment . The changes there began in 1808 and were intensified again after Napoleon separated from his first wife and decided to receive his fiancée, Princess Marie-Louise of Austria , in Compiègne on March 27, 1810. A total of 300 workers were employed on the construction site, whose operation was personally monitored by Napoleon. Work ended in 1810, and Napoleon's initials in many parts of the castle still tell of the changes made under him. The work in the palace gardens lasted longer than the structural changes. Hardly anything remained of the French garden begun under Jacques V. Gabriel. That is why Napoleon had commissioned his architect Berthault to re-create the palace garden, creating a creative connection between the building complex and the neighboring forest of Compiègne. Berthault had the palace gardens redesigned and planted in the English landscape style from January 1812 , and in 1810, at Napoleon's request, created a more than four kilometer long visual corridor from the palace terrace to and through the forest; the so-called avenue des Beaux Monts . In order to be able to drive the carriage from the forest directly to the castle, the emperor also had a wide ramp put up in the middle of the terrace. When all the work was completed, the Compiègne Palace Park was as large as the Tuileries in Paris .

The imperial couple hardly used the palace complex with the exception of short stays when passing through. From November 1813 to January 1814 Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte , who had been expelled from his kingdom of Westphalia , stayed there after his wife Katharina von Württemberg had stayed in Compiègne for a few days in March 1813. In the course of the Wars of Liberation , 18,000 Prussian soldiers besieged the palace and town in March / April 1814 . The Major François Ot (h) enin was the superior force initially resist and fight back a first attack, but on April 4, the city finally had yet to surrender . However, the facility was only slightly damaged in the associated fighting.

Restoration and July Monarchy

After his return from exile in England , Louis XVIII. At the end of April 1814, on his way to Paris, he briefly stopped at Compiègne Castle. In his entourage was Ludwig's niece Marie Thérèse Charlotte de Bourbon , Duchess of Angoulême and daughter of Louis XVI., Who had lived in the castle when she was a child. There the new king also received the Russian Tsar Alexander I , before continuing on his way to the capital on May 2nd. Louis XVIII It was also who began to have the Napoleonic symbols removed from the architectural decor of the castle, but this was never completely carried out, so that even today the initials of Napoleon Bonaparte can often be found there.

In the years that followed, Compiègne was used only rarely and only for a few days by the royal family, who came to these stays with a small state. Only under Charles X did the stays again become longer and more frequent. The most important event during the July Monarchy was the wedding of Princess Louise d'Orléans , daughter of Louis-Philippe I , to Leopold I , King of the Belgians, in the palace chapel on August 9, 1832 . On this occasion, Louis-Philippe commissioned Frédéric Nepveu , the palace's architect since May 1832, not only to repair the chapel, but also to transform the ballroom into a theater. Nepveu had only a few weeks available for this, and the work on this was far from over when the theater was inaugurated on August 10, 1832 with the performance of two comic operas . The renovation was not fully completed until 1835.

Renewed bloom in the Second Empire

At the beginning of the Second Republic , Compiègne Castle became national property in 1848, and from then on a state administrator took care of it. The plan arose to turn the castle into a state retirement home, but this was never implemented. The then President and later Emperor Charles Louis Napoléon had the building open for viewing, and so the historic apartments already had 2,000 visitors in 1849. A year after his coup d'état , the new French Emperor stayed in Compiègne for a first long stay in December 1852. Among the invited and traveled guests was a young Spanish countess named Eugénie de Montijo , the Napoléon III. made Empress of the French by marriage the following month. From 1856 onwards, the couple hosted large hunting festivities in Compiègne every autumn. These so-called series were week-long meetings in November and December, to which around a hundred people were invited and which took place in four to six consecutive weeks. The guests were politicians, diplomats, writers, artists and scientists, but also high-ranking military officials and foreign kings and princes. They included the Prussian King Wilhelm I , Ludwig II of Bavaria , the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I , Giuseppe Verdi , Eugène Delacroix , Franz Xaver Winterhalter , Gustave Flaubert , Alexandre Dumas , Louis Pasteur and Marshal Patrice de Mac Mahon . Up to 900 people were accommodated in the palace complex during the séries . They were all brought to Compiègne by special train from the Gare du Nord in Paris , where they awaited hunting trips, games, concerts and theater performances in a rather informal atmosphere. The entertainment also included trips to Pierrefonds to see the progress of the castle restoration , or to excavations under Albert de Roucy , which Napoleon III. initiated, for example Champlieu ( Orrouy municipality ) and Mont-Berny. Prosper Mérimée's famous dictation was also used to distract the guests , a text that was peppered with numerous linguistic difficulties and which none of those present could put on paper without errors. Napoleon III made 42 mistakes, his wife 62. Alexandre Dumas did better with 24 mistakes. But the best result of this dictation came from a foreigner: the text of the Austrian ambassador Richard Klemens von Metternich had only three errors.

Little by little, the imperial couple changed the furniture in their apartments. Empress Eugénie was particularly involved in the redesign. She replaced the outdated and outdated furniture from the Napoleonic period with furniture in the style of the Second Empire and mixed this with pieces in the Louis-Seize style, which she had bought in memory of Marie Antoinette, whom she admired. These included original pieces from the possession of the former queen from Saint-Cloud Castle. On the second floor of the wing facing the garden, Napoleon III. set up a smoking room for the male guests of the séries . Architecturally, too, he left his fingerprint. In 1858 he commissioned the architect Jean-Louis Victor Grisart to build a connecting building between the kitchen wing and the wing of the palace that housed the ball gallery . In the following year, the building was completed and stood in the place that Ange-Jacques Gabriel had planned for a new castle chapel that had not been built. The connecting building cut the former kitchen courtyard into two parts, of which the southern one has since been called cour de la Régie . The ground floor of the new building served as accommodation for officers, while the upper floor was taken up by a single large room. This was named Natoire-Galerie , after the cycle of paintings by the painter Charles-Joseph Natoire hung there . In the gallery , which was only set up under Grisart's successor Gabriel-Auguste Ancelet , soirées and concerts were held during the Second Empire , or it was used as a dining room for smaller parties . In 1866 Napoleon III took an even bigger architectural change is under way: the construction of a new and larger palace theater because the old one in the former ballroom had become too small. The Ancelet commissioned with the design and execution borrowed from the Theater of Versailles and began construction in 1867, which was almost finished in 1870. The only thing missing was the painting inside. The opening was scheduled for 1871, but that was not to come.

The first years of the Third Republic

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War and the accompanying proclamation of the Third Republic gave Napoleon III's construction plans. and the lively events in Compiègne came to an abrupt end. In August, a hospital with a total of 300 beds was set up in the castle. It occupied all the larger rooms of the complex including the hall of the guards , ball gallery and Natoire gallery , but was never put into operation, because on September 20, 1870 300 Prussian soldiers took Compiègne and occupied the castle for eight days. When they left, they took numerous items of furniture with them, including 900 woolen blankets. On November 20, the Prussian General Kurt von Manteuffel and his General Staff moved into quarters in the complex and stayed there until March 12, 1871. During their stay, they used the supplies still stored in the castle, including drinking 12,400 bottles of wine. The Prussian troops stayed until October 7th. While they were housed in the castle, a fire broke out and destroyed a ten-meter-long section of the roof structure.

After the war, a Gallo-Roman museum was set up in the hall of the guards and a Khmer museum in the vestibule , in order to cover part of the horrific maintenance costs for the building complex. A tapestry gallery was added in 1880 , and a gallery with engravings in 1884 . The historic apartments could be viewed again since 1871. In 1889 the French government began to distribute the valuable interior decoration to other institutions and buildings. Much furniture and numerous works of art were used to equip embassy buildings and ministries. The French National Library ( French Bibliothèque nationale de France ), the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal and the Sainte-Geneviève library received the majority of the books in the palace library . At least 8,900 volumes remained in the city and were transferred to the city library there. In 1890 all carpets were removed from the large apartments and sent to Paris so that the President of the Republic could choose a few pieces for his residence from this selection. Not one of the valuable carpets returned to the castle. This was finally completely emptied, so that for a stay there by the Russian Tsar Nicholas II and his wife Alix von Hessen-Darmstadt in September 1901, 20 railway wagons with furniture and furnishings had to be brought in.

The 20th century

During the First World War , the British Field Marshal French pitched his tents in the castle with his staff for three days from August 27, 1914, but then fled from the advancing German troops who occupied Compiègne on September 2. But the German soldiers did not stay long either, because on 12/13. In September they were driven out by French dragoons . The French armed forces operated a 400-bed hospital in the castle from October, which was set up there until March 26, 1917. Then this gave way to the Grand Quartier Général (GQG), the high command of the French army , which moved into the castle in April 1917 and stayed there until March 25, 1918 before moving on to Provins . Both under General Robert Nivelle and under Philippe Pétain , the former bedchamber of Queen Marie Antoinette served as a study. After the departure of the GQG, the palace complex was used as the headquarters of the 3rd French Army under General Georges Louis Humbert . Bomb hits severely damaged the palace complex on September 1, 1918, but the valuable interior was not damaged, as it had been brought to safety in Paris from August 1915 after a bomb attack in March of that year. The rescued furnishings not only included furniture, but also paneling and overhangs . After the end of the war, the evacuated facility was returned to the castle in April 1919. The war damage to the buildings, which were meanwhile being used by the prefecture of Oise, had not yet been completely repaired when a fire started on the night of December 13-14, 1919, in which part of the emperor's apartment burned out. The emperor's bedroom and the adjoining advisory room were completely destroyed, but the furniture was saved.

As a precaution, the furniture was also removed from the castle during the Second World War . It was stored in Chambord Castle from 1939 and returned to Compiègne after the war. However, in the post-war years, the individual pieces of furniture were not necessarily put in their historically traditional place, but were randomly distributed in the rooms. From 1945, however, a comprehensive restoration of the buildings and interiors began under the architect Jean Philippot. There were three possible restoration eras for the restoration of each room: the time of Louis XVI. (too little was preserved from the time of Louis XV), the time of the First Empire, from which numerous pieces of furniture and in many rooms also the decoration were preserved, or the time of the Second Empire, to which the majority of the furnishings at that time could be assigned. Those responsible made this decision for each room individually, and so today you can find furnishing ensembles from all three style periods in the historic apartments. To restore it, not only were the room decor restored and furniture and furnishings from the castle brought back to Compiègne, but fabrics for seating furniture and for use as curtains and wall coverings were also produced according to original templates.

description

The outer

The palace complex has a roughly triangular floor plan and covers an area of over two hectares. The numerous wings of the building are grouped around five large and two small inner courtyards, the courtyard of honor ( French cour d'Honneur ), the cour de la Régie , the courtyard of the baths ( French cour des Bains ), the cour des Pompes , the chapel courtyard ( French cour de la Chapelle ), the covered today Küchenhof ( French cour des Cuisines ) and Orangeriehof ( French cour de l'Orangerie ), formerly also cour des offices was called. Although the majority of it was built in the time of Louis XVI, i.e. in the Rococo, the architecture shows the characteristics of Louis-quinze and thus an unadorned severity. All wings of the building have three floors: a rusticated ground floor, a bel étage and a low mezzanine floor with a flat gable roof and balustrade . The individual floors are separated from each other by cornices . On the rear side of the garden, the palace terrace supported by the former city wall is at the same height as the bel étage and thus above the level of the palace park. This creates the impression in the apartments that you are on the ground floor. The garden facade is 193 meters long and has 49 rows of windows.

The visitor enters the palace complex from the Place d'Armes from the south and reaches the main courtyard through a 43 meter wide colonnade . The portico consists of Doric columns, the entablature of which is covered with a balustrade. To the left, on the north-western side of the courtyard, is the Marshal's Wing ( French aile des Maréchaux ), which now houses a museum. In the north-east of the courtyard is the former main wing of the castle, whose representative function was taken over in the 18th century by a new wing on the garden side. It has a central projection , the triangular gable of which is supported by four Ionic columns. The motif of the central risalit is repeated on the south end of the Marshal's wing facing the Place d'Armes and the wing opposite it in the main courtyard, but these have pilasters rather than pillars .

inside rooms

Today, the majority of the interiors are in the state of the First and Second Empire. From the original furnishings from the time of Louis XV. practically nothing has survived, because his successor had the facility completely redesigned between 1782 and 1786. Only a few panels of the white-painted paneling have survived to this day because they were used under Louis XVI. were moved to unimportant and therefore less frequented places. Although Louis XVI. and his wife Marie Antoinette did not paint the walls and wall coverings in white to give the rooms a bright and fresh look, but on the initiative of the then commissaire général du Garde-Meuble de la Couronne ( German general commissioner of the royal furniture warehouse ), Thierry de Ville-d'Avray, made some gilding because the furnishings at that time seemed too simple to him. The equipment of that time is still in the game room of the Queen , the card parlor , the advisory cabinet and the hall of the guards received.

Emperor's apartment

The Emperor's apartment ( French appartement de l'Empereur ), in the Ancien Régime known as the King's Apartment ( French appartement du Roi ), is the central part of the residential wing. It is the only batch that has never been rededicated during the roughly 260-year history of the castle, but has always been the living room and representative room of the respective sovereign . The sequence of rooms begins with a large anteroom ( French antichambre ), which was once called the salon des Huissiers . In the pre-Napoleonic era it served as a common antechamber for the apartments of the king and queen, which is why it was also known as the double antechamber ( French antichambre double ). The room is equipped with a fireplace made of red marble , which dates to the 17th century and thus comes from the predecessor of today's castle. A portrait of Louis XVI hangs over the fireplace. in coronation regalia , a copy of the painting by Antoine-François Callet . On one of the long sides is the allegorical painting Neptune or the Triumph of the Navy by Pierre Mignard , which the latter made for Versailles in 1684. It hung there in the queen's anteroom before it came to Compiègne in 1739.

From the anteroom the visitor arrives in the dining room of the emperor ( French salle à manger de l'Empereur ), which was built in the time of Louis XVI. was used as another anteroom. In the Second Empire it also served as a small theater for revues and charades . Its mahogany furniture by François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter is a reconstruction as it was in 1807/1808. The large Bohemian crystal chandelier dates from the 18th century. The walls are divided vertically by white pilasters with Ionic capitals. Their painting simulates marble, while the fireplace in the room is made of real white marble. The painting of the wall surfaces between the pilasters imitates onyx marble . The overhangs consist of trompe-l'œil paintings in grisaille technique and are the work of Piat-Joseph Sauvage , who worked in Compiègne Castle from 1784 to 1789.

The so-called card salon ( French salon des Cartes ) can be reached from the emperor's dining room and can also be entered directly from the anteroom. He has had his name since 1865, when three large maps of Compiègne and the surrounding area were hung on the walls. Under Louis XVI. this room was called the antichambre des Nobles , while under Napoleon it was used as the salon des Grands Officiers and under Napoleon III. was known as the salon des Aides de Camp . Pierre-Denis Martin made two of the maps between 1738 and 1739. They were previously hanging in the dining room of the small apartment . Five of the tables in the card room are also from there. Their tabletops show maps of the five most important royal possessions during the Ancien Régimes: Marly-le-Roi , Saint-Germain-en-Laye , Fontainebleau, Versailles and Compiègne. In the Second Empire, the room was used as a reception and games room, as indicated by a shuffleboard and Japanese billiards from 1862.

The next room in the sequence is the family salon ( French salon de Famille ), the former bedroom of Louis XVI. with a view of the castle park. The room not only takes up the height of the first floor, but also of the mezzanine above and lies exactly in the central axis of the park. Since the First Empire, however, it was no longer used as a bedroom, but as a salon and reception room. The idea of setting it up as a throne room was never implemented. The paneling has pilasters with Corinthian capitals and dates from the time of Louis XVI. The same applies to the Sauvage overhead portals, which show four phases of a day: sleep, waking up, getting up and eating. Emperor Napoleon III. and Empress Eugénie had this room changed. The stucco decorations on the ceiling date from 1855. Three years later, the furniture was renewed in the Louis-quinze style. Eye-catchers, next to a table made of Saint-Cloud with marquetry made of rosewood , are two candelabra that are carried by children on the shoulders of an Indian and an Indian woman. They stand on a base made of green malachite with gold-plated bronze applications in the form of the initials of Napoleon III. and his wife. A valuable chest of drawers from 1784 by cabinet makers Joseph Stöckel and Guillaume Bennemann , which can be seen in the Louvre today, comes from this room.

Directly behind the family salon is an advisory cabinet ( French cabinet du Conseil or salon du Conseil ) called a conference room. There the king held meetings with his advisors, because Compiègne was the third palace in France, next to Versailles and Fontainebleau, to hold royal councils. The room was reconstructed in its 18th century state in 1964 and shows on the wall a silk painting by François Bonnemer based on van der Meulen's work by Ludwig XIV crossing the Rhine. The painting was previously smaller and was enlarged by Jacques-Claude Cardin especially for this room in 1785 .

The room following the advisory cabinet served under Louis XVI. as a powder cabinet ( French cabinet à la Poudre ) and was converted under Napoleon into the emperor's bedroom ( French chambre à coucher de l'Empereur ). Napoleon III used it as a conference room for meetings with his ministers. This room was completely destroyed in a fire in 1919, but the furniture could be brought to a safe place from the fire. At the beginning of the 1970s, the room - with the exception of the ceiling - was reconstructed in the style of the First Empire and furnished with the original furniture from the Napoleonic era. This gold-plated wooden furniture comes from the Jacob-Desmalter workshop. Seat covers, curtains and wallpapers are all coordinated in color and pattern.

After the emperor's bedroom, the last room in the apartment is the library, which was also furnished by Napoleon and used by him as a study. The partially gilded furniture is made of mahogany wood and again comes from Jacob-Desmalter. The ceiling painting is the work of Anne-Louis Girodet and shows Minerva between Apollo and Mercury . A secret door hidden behind simulated books leads to the empress' apartment . Today's book inventory is not original, but came in 1901 on the occasion of a visit by Tsar Nicholas II on the then completely empty shelves. It is planned, however, to replicate the holdings of the imperial library using inventory lists from 1808 and 1818.

On the west side of this imperial large apartment ( French grand appartement ), which was used for representation, is followed by a suite of smaller, private rooms called the small apartment ( French petit appartement ). These include, for example, the small cabinet ( French: petit cabinet ) and a bathroom with simple furniture made of plane wood that is almost entirely without decorations. The room served under Louis XVI. as a library. Napoleon Bonaparte had his own apartment built in part of these rooms for his secretary Claude François de Méneval and, in return, set up another petit apartment on the mezzanine floor, which included a card cabinet that served as a study . However, the rooms in the mezzanine were no longer used shortly after the restoration began .

Apartment of the Empress

The apartment of the empress ( French appartement de l'Impératrice ) adjoins the apartment of the emperor to the north . This sequence of rooms was originally used by the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand and his wife Maria Josepha von Sachsen. After Louis Ferdinand's death in 1765, his four sisters moved there before the rooms were temporarily converted into an apartment for Queen Marie Antoinette. His wife Marie-Louise lived there under Napoleon. Used by the Duchess of Angoulême from 1815, his widowed daughter-in-law Maria Karolina of Naples-Sicily followed in the time of Charles X as a resident, before the queen moved in again in the time of Louis-Philip and finally the apartment was occupied by Empress Eugénie in the Second Empire. All rooms - with the exception of the music salon - have been restored to their condition from the First Empire.

The first room of the apartment is the so-called deer gallery ( French gallery des Cerfs ), which has served as an anteroom for the empress's apartment since the First Empire . From there, the visitor arrives at the gallery of the hunts ( French galerie des Chasses ). This room was set up as a painting gallery under Napoleon in 1808, in which 35 works from the Louvre were exhibited. In 1832, King Louis-Philippe exchanged these paintings for 24 works by Charles Antoine Coypel , which is why the room was called Galerie Coypel at the time . The pictures dealt with the Don Quixote story and stayed there until 1911. The current name of the room comes from nine tapestries with hunting scenes, which Louis XV. for the king's apartment at the time. Until 1795 the tapestries hung in the royal bedroom, in an anteroom and in the advisory cabinet . The wall hangings were made from cardboard by Jean-Baptiste Oudry between 1736 and 1746 and have been in this room since 1947. An identical set of tapestries is on display in the Uffizi today .

The gallery of the hunts leads to an anteroom that was converted into the dining room of the Empress in Napoleonic times ( French salle à manger de l'Impératrice ). Because it was also used as a salon during the Second Empire, this room was also known as the First Salon ( French premier salon ). Napoleon and Marie-Louise of Austria dined there on the evening of their first meeting. The wall painting imitates antique yellow marble, the overhangs show motifs in trompe l'oeil technique. The majority of the furniture is by Jacob-Desmalter, while the coffered stucco ceiling was designed in 1815 by an artist named Morgin.

The next room in the apartment is the flower parlor ( French salon des Fleurs ), which is also simply called the second salon ( French deuxième salon ) or the Empress's game room ( French salon des Jeux de l'Impératrice ). The furnishings and decor were commissioned at a time when Napoleon Bonaparte was still married to Joséphine de Beauharnais . They were only marginally adjusted for his second wife after the divorce. Eight pictures of lilies by Étienne Dubois hang on the walls, based on models from Pierre-Joseph Redouté's publication The Lilies . They were placed there on the occasion of Marie-Louise's arrival in 1810. The ceiling painting, however, comes from Anne Louis Girodet. In the past, the decor of this room often featured the letter N (for Napoleon), but this was changed in 1815 to the initials Marie Thérèse Charlotte de Bourbons because she was using the apartment from that year. The covers for the seating furniture manufactured by Jacob-Desmalter come from the tapestry manufactory. After the birth of her son, Eugénie de Montijo set up this room as the prince's bedroom in 1812 so that he could have it close by. At the same time, the neighboring Blue Salon ( French salon Bleu ) was rededicated as a study and playroom for Napoleon Franz . Before that, the Empress received guests there in private. The painted ceiling decorations are by Dubois and Rédouté, while the history paintings are by Girodet. They tell the story of a warrior. This salon takes its name from the blue wall coverings that contrast with the red marble of the fireplace and the skirting boards .

The large reception room ( French grand salon de reception ) can be reached from the flower parlor . This is also called the Salon of the Ladies of Honor ( French salon des Dames d'Honneur ) or third salon for short ( French troisième salon ). There the Empress received her guests in a larger and official setting. The wall painting from 1809 imitates marble and comes once again from the studio of Dubois and Redouté. You are also responsible for the decor of the wall pilasters and for the ceiling painting. Jacques-Louis Dubois' overlaports show the ancient goddesses Minerva, Juno , Flora , Ceres , Hebe and Diana . The elaborately designed fireplace consists of dark marble and green granite with gold-plated applications. The covers of the seating furniture are still original from 1809 and show the initials Joséphine de Beauharnais in the form of peach blossoms. Three large porcelain vases from the manufacture in Sèvres complete the sumptuous furnishings.

From the large reception room you can get to the Empress’s bedroom ( French: chambre à coucher de l'Impératrice ), the most splendidly furnished room in the entire castle. As in the emperor's bedroom , wall decorations, seat covers and curtains are coordinated in color and pattern. The gold-plated furniture comes from the Jacob-Desmalter workshop, as does the luxurious four-poster bed, whose curtains made of white silk and gold-embroidered muslin are held up by two gold-plated wooden angel statues. The two large mirrors in the room are flanked by paintings by Girodet. Three of them show the seasons of summer, autumn and winter. The fourth painting belonging to the cycle, the spring allegory, was destroyed together with two other paintings in 1870 when the castle was taken by Prussian troops. In the 18th century, this room - like the neighboring music salon - belonged to the king's apartment and was used as a gaming room before it was redesigned under Napoleon by Louis Martin Berthault from 1808 to 1809 as a bedroom for the then Empress Joséphine. However, she never saw the room in its finished state, let alone used it. The bedroom has a small boudoir that the Empress used as a dressing room and bathroom. The circular room has no windows, but a glass dome for lighting. The colors white and gold dominate its furnishings.

From this boudoir or directly from the bedroom of the Empress is the music room ( French salon de Musique ) to achieve. As the only room in the Empress's apartment , it was restored to the state of the Second Empire. At the same time, however, this means that there is primarily furniture from the 18th century, which Empress Eugénie brought together in this room in memory of Marie Antoinette, including some from the queen's large cabinet in Saint-Cloud Castle. Eugénie had other pieces of furniture brought to Compiègne in 1862 from the lacquer cabinet of the Parisian Hôtels du Châtelet in rue de Grenelle (today the building is the seat of the French Ministry of Labor). A gilded gueridon with a table top made of white marble, on the other hand, comes from the Quirinal Palace in Rome, while the chandelier came from the Tuileries Palace. Two tapestries with oriental motifs hang on the walls. They come from the royal manufacture in Beauvais from the end of the 17th century . The music salon was under Louis XVI. used as a private dining room, during the July monarchy it served as a billiard room. A piano forte by Sébastien Érard and a harp point to later use during the Second Empire . The over-portals depicting children's games originally adorned the doors of the king's apartment .

The last room in the room sequence of the Empress is the breakfast salon ( French salon de Déjeun ), a room that was reserved exclusively for the Empress and a few intimate friends for gatherings. Originally set up for Marie-Louise, the room has wallpapers and curtains with the same colors and patterns: Both are made from yellow silk lampas and show white arabesques with a blue and white border as a motif . The furniture in the breakfast salon is less luxurious than that of the rest of the salons in the castle.

Apartment of the King of Rome

In the courtyard of honor there is a side entrance to the historic apartments on the right in the middle of the southeast wing. Behind this is a staircase with the Queen's staircase ( French escalier de la Reine ). Since the First Empire, it has also been called the Apollontreppe ( French escalier d'Apollon ) because of a statue of Apollo in a niche on the landing . It was completed in 1784 according to a design by Louis Le Dreux de la Châtre and has a wrought-iron railing that was made by the Compiègne blacksmith Raguet and installed two years later. Via the stairs the visitor arrives at the former apartment of the queen , which is now called the apartment of the king of Rome ( French appartement du Roi de Rome ). At the time of Louis XVI. this area of the castle was inhabited by his wife Marie Antoinette. Napoleon temporarily housed the deposed Spanish King Charles IV there in 1808 and, after his departure, transformed the rooms into a splendidly furnished guest apartment for foreign rulers. Among other things, Napoleon's brother Louis , King of Holland , and his wife Hortense used the rooms before they became his apartment after the birth of Napoleon's son Napoleon Franz in 1811. However, the King of Rome only lived there during a single stay in Compiègne in 1811. In 1814 Louis XVIII, who had returned from exile, stayed. on his way to Paris for a few days in this apartment because he did not want to live in the rooms of the imperial apartment with its numerous Napoleonic symbols. His brother then used these rooms before he ascended the French throne as Charles X in 1824, clearing the space for his son Louis-Antoine , Duke of Angoulême, and his wife Marie Thérèse Charlotte. In the July monarchy, the rooms that were called Apartment A at that time were occupied by the king's son, Ferdinand Philippe , Duke of Orléans. Napoleon III's cousin, Princess Mathilde , followed him as a resident during the Second Empire . During the restoration of the apartment, all rooms with the exception of one were restored to the state of the First Empire and the rooms were furnished with the original furniture of that era. All rooms have white paneling and silk wallpaper on the walls.

The Queen's staircase ends on the first floor in a small anteroom that leads to a second anteroom. From there, the visitor through a small granite gallery ( French petite galerie du Granit ) or Small granite corridor ( french corridor petit du Granit ) said narrow hallway to the large hall of the apartments of the Emperor , which used to be the apartment of the queen belonged. Today you enter the sequence of rooms from the second anteroom, which leads into the first salon ( French premier salon ). This room is also known as the wedding salon ( French salon des Noces ) because in it hangs the tapestry Roland or the wedding of Angelica after a cardboard box by Charles Antoine Coypels. The wall hanging was made in the tapestry manufactory between 1790 and 1805. In the Napoleonic era, the salon served as a playroom. The overhangs consist of grisaille paintings by Piat-Joseph Sauvage, which show the six muses Klio , Euterpe , Thalia , Melpomene , Urania and Erato . The furniture in this room was made by the cabinet-maker Pierre-Benoît Marcion .

After the wedding salon following game room of the Queen ( French salon des Jeux de la Reine ), and Second Salon ( French second salon ) called. It is the only room in this apartment that was not in the style of the First Empire from 1952 to 1956, but in the state of the time of Louis XVI. has been restored. The supraports were made by Sauvange in 1789 and show the four elements as children playing. The furniture of the salon includes two chests of drawers by Guillaume Bennemann with gold-plated bronze ornaments that resemble Queen Marie Antoinette's initials.

The following room is the bedroom of the King of Rome ( French chambre à coucher du Roi de Rome ), which originally served as Marie Antoinette's bedroom. His Sauvage Supraport from 1784 shows the four seasons. The sculptor Randon and Pierre-Nicolas Beauvallet were responsible for the ornamental decoration of the room . The blue and gold covers of the seating furniture were originally made for the Joséphine de Beauharnais bedroom in Saint-Cloud Castle, as were the two striped silk wallpapers to the right and left of the four-poster bed. The bedroom is furnished with four paintings with Pompeii motifs from 1810, which come from the atelier of Dubois and Redouté.

A door leads from the bedroom of the King of Rome to a small boudoir, the furniture of which was already there during the times of the Spanish ex-King Charles IV. A spacious bathroom adjoins the room. This room was changed during the Second Empire, but with the restoration work of the 20th century it was returned to the state of the First Empire. Four columns with Corinthian capitals frame the green glazed bronze tub with fittings in the shape of a swan. The last room in the sequence is a small salon, which is called a boudoir salon ( French salon-boudoir ) due to its intimate character .

Princely double apartment

From the stairs of the Queen , too, is princely double apartment ( french apartment double de Prince ) distance. It also has a connection to the apartment of the King of Rome . The reason for this is to be found in the fact that the rooms were intended for Marie Antoinette's two children, the Dauphin Louis Charles de Bourbon and his sister Marie Thérèse Charlotte. Napoleon refurbished the rooms in 1807 to accommodate a foreign prince couple. The suite of rooms has had its current name since then, as it had two bedrooms. In 1808 part of the apartment was occupied by the Spanish ex-Queen Maria Luise of Bourbon-Parma . In 1810 Napoleon's younger brother Jérôme Bonaparte and his wife Katharina von Württemberg used the rooms, and again from November 14, 1813 to January 10, 1814, after they had been expelled from their Kingdom of Westphalia . During the reign of Charles X, they were first followed by the Duke and Duchess of Berry, Charles Ferdinand d'Artois and Maria Karolina of Naples-Sicily, and then Marie Thérèse Charlotte de Bourbon, who thus lived in the same rooms as in her childhood. During the July monarchy, the sequence of rooms was called Apartment B and was used by Louis-Philippe's sons. Divided into three smaller apartments called Apartment B1, B2 and B3 during the séries of the Second Empire , the rooms were used to accommodate particularly important guests, such as Napoléon Joseph Charles Paul Bonaparte and his wife Marie Clotilde of Savoy .

All nine rooms were restored to the state of the First Empire. Crossing an anteroom, the visitor of the apartment reaches a dining room and then a room called the first salon ( French premier salon ), which served as a waiting room and has only simple, painted furniture. It is followed by a second salon ( French second salon ), which at the time of Louis XVI. was the Dauphin's bedroom. Today there is no longer a bed in the room, but rather tables and chairs from the workshop of Pierre Benoît Marcion, which show that this salon was used as a playroom under Napoleon. The wall covering is a gold damask that was originally made for the small Salon Joséphine de Beauharnais in Saint-Cloud, but was never used there.

Today the Prinzliche Doppelappartement only has one bedroom, called the large bedroom ( French grand chambre à coucher ). Its architectural decor is from the 18th century. The over-portals with grisaille paintings are by Piat-Joseph Sauvage, but were placed in a different room before the Napoleonic era. Two paintings showing children at play previously hung in the king's powder cabinet . The furniture is in Empire style and comes from the Jacob-Desmalter workshop.

The apartment also had a small anteroom, a walk-through room, the so-called side salon ( French salon latéral ) with three tapestries from the tapestry manufactory and the salon circulaire , in which a fireplace is installed that dates back to Charles V's predecessor building.

other rooms

From the courtyard of honor , the visitor enters a vestibule through the main portal , which is called the column gallery ( French gallery des Colonnes ). The 53.6 × 12 meter hall takes up the entire ground floor of this wing. It is divided into three naves by two rows of Tuscan columns and has a ceiling with a shallow barrel . The black and white tiles of the floor are laid in a geometric pattern. In the 18th century the columned gallery was completely empty and unadorned. It was not until the First Empire in 1808 that today's eight busts of Roman emperors were erected. The lighting does not come from electricity, but from four large candlesticks with oil lamps.

The vestibule leads to a two- flight staircase of honor called the King's Staircase ( French grand degré du Roi or escalier du Roi ). It has an elaborately made, wrought-iron railing from the 18th century, which, as in the case of the Queen's staircase , was made by the blacksmith Raguet according to designs by Louis Le Dreux de la Châtres. It is plated with silver and gold . Under Napoleon, the decor of the staircase was changed to designs by Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine and the ceiling was raised. Their painting comes from the Dubois and Redouté workshops. On the landing is a Gallo-Roman sarcophagus , which was previously used as a baptismal font in the Saint-Corneille abbey church .

The King's staircase connects the vestibule on the ground floor with the hall of the guards ( French salle des Gardes ) on the bel étage. This room was from 1960 in the state of the time of Louis XVI. restored. In the First Empire it was called Galerie der Minister ( French galerie des Ministres ) because ten portraits of French ministers were hung there. The cornice of the barrel-vaulted hall rests on a frieze of helmets in the form of torn snapdragons with fleur-de-lys between them. The sculptural decor comes from Pierre-Nicolas Beauvallet, as are the pilasters on the walls, whose fluting has the shape of lances. Beauvallet also made the two reliefs above the doors showing mythological figures.

One of the two doors in the hall of the guards leads to the castle chapel after crossing an anteroom. It is a successor to the chapel built by Charles V on the same site. Measured against the size of the entire palace complex, this church building is comparatively small. A larger chapel was planned by Ange-Jacques Gabriel in the 18th century, but never realized. During the First Empire, the furnishings were revised by Ambroise Joseph Thélène based on designs by Louis Martin Berthault. The chapel received most of its current furnishings during the July monarchy, when King Louis-Philippe had galleries with gilded furniture installed on the long sides and new glass windows on the occasion of the wedding of his daughter Louise . These come from the Ziegler workshop in Sèvres . The statues on the floor are copies of sculptures from the heart tomb of the Duke of Longueville , Henri d'Orléans . The originals have been in the Louvre since 1845.

From the chapel vestibule , you can go to the gallery des Revues and the ball gallery ( French galerie de Bal , also known as galerie des Fêtes ). Napoleon had the 45 × 13 meter large and 10 meter high ballroom furnished from 1809. During the séries in the Second Empire, it was not only used as a ballroom , but also for large banquets with more than 100 people. It is spanned by a barrel vault, which is supported on its long sides by a total of 20 Corinthian columns with gilded capitals and fluting. The ceiling painting from the workshops of Louis and Étienne Dubois and of Antoine and Pierre-Joseph Redouté was realized between 1811 and 1812. It imitates a coffered ceiling and shows the most important military successes of the emperor, for example Rivoli , Moscow and Austerlitz . The paintings on the front of the room are by Anne Louis Girodet. He painted the mythological scenes in the period from 1814 to 1816, replacing Napoleon Bonaparte's coat of arms that had previously been there. The reliefs above the doors are the work of the sculptor Charles-Auguste Taunay . They show ancient gods and heroic figures. The two white marble statues in the ball gallery depict Napoleon and his mother Laetitia Ramolino . They are copies of sculptures by Antoine-Denis Chaudet and Antonio Canovas . Napoleon III had it placed there in 1857 in memory of his ancestors.

Also from the galerie des Revues is the 1858 under Napoleon III. The Natoire gallery ( French gallery Natoire ) can be reached. Its interior work was completed in 1859. It was named after the painter whose nine paintings with motifs from the story of Don Quixote are hung there: Charles-Joseph Natoire. He had made them between 1734 and 1743 on behalf of Pierre Grimod du Fort, Count von Orsay, as cardboard boxes for tapestries intended for Grimod's Paris residence, the Hôtel de Chamillart. They have been hanging in the Jagden Gallery since 1849 before they were moved to their current location. The count had commissioned a total of ten templates, but the tenth is not in Compiègne Palace, but in the Louvre. The wall hangings made from the cardboard boxes can be seen today in the Musée des Tapisseries in Aix-en-Provence . Other special pieces of equipment are two vases from the porcelain factory in Sèvres from 1867 and furniture by Jacob-Desmalter and Joseph Quignon . The Natoire gallery has two anteroom at the front of the room. In one of them there are showcases with exhibits from the former Gallo-Roman museum of Napoleon III.

Today the Natoire gallery leads to a bridge, which in turn leads to the Imperial Theater ( French théâtre impérial ) on the other side of the rue d'Ulm . This 1200 seat theater was built in 1867 by Napoleon III. commissioned, but remained unfinished due to the events of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). It was only opened as a concert hall in 1991. Its interior design is inspired by the Opera of the Palace of Versailles .

The Imperial Theater , sometimes also called Great Theater ( French grand théâtre ) in connection with the castle , was to replace the old Small Theater ( French petit théâtre ). This was set up in 1832 on the occasion of the wedding of Princess Louise d'Orléans with Leopold I of Belgium in the Ballhaus ( French jeu de paume ) and offered space for up to 800 spectators. However, after the crinoline found its way into fashion, the Small Theater only held 500 people. Étienne Dubois was responsible for the wall and ceiling paintings. Completed in 1835, the small theater was already equipped with central heating. Its wooden backdrop technology, including twelve stage sets from Pierre-Luc Cicéri's studio, is still in its original form. The large chandelier was made by Napoleon III. brought from the Tuileries Palace.

The guest library ( French bibliothèque des invités ) has been preserved in the mezzanine of the queen's wing . Napoleon III furnished it in 1860 for those invited to the séries with furniture by Victor Marie Charles Ruprich-Robert based on designs by Jean-Louis Victor Grisart . The room has not yet been restored and is therefore in its original state from the 19th century.

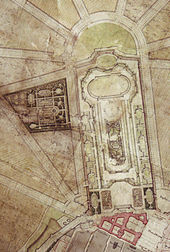

Castle park and garden

As early as the 16th century, Compiègne was under Charles IX. landscaped castle garden handed down. In 1684 - as one of the few changes he made to the complex - Louis XIV had a small baroque garden, the jardin bas , laid out in one of the castle courtyards , which later fell victim to renovations. The basic layout of today's palace gardens, known as the Little Park ( French petit parc ) and located to the east of the palace complex, goes back to a design by Ange-Jacques Gabriel from the mid-18th century, which was inspired by the gardens in Marly . The plan was never fully implemented due to financial difficulties, and the garden was not finished when the French Revolution broke out. Gabriel's plans included a 700 × 280 meter garden area with water features and broderie parterres , between which lawns stretched. Along the long sides of the garden were avenues that met at the southeast end and formed a semicircle. To the north of the garden, Louis XV. had a pleasure palace , the so-called hermitage , built for Madame de Pompadour , which is no longer preserved today. With the exception of two elongated groups of linden trees on the long sides of the garden, nothing has survived from the plantings carried out under Gabriel and his successor , because in 1798 all the smaller beds and plantings were destroyed when the castle was used as a barracks. The situation is similar with the shrubbery of the King ( French bosquet du Roi ), which in the 18th century on the northern tip of the castle on a plateau for porte Chapelle was built gate above and the bosquet of the Queen ( French bosquet de la Reine ) a Possessed counterpart at the southern tip. While the latter still exists today, the king's bosquet was replaced by a rose garden in 1820, which also included a heated greenhouse . The garden was reconstructed in the late 1990s based on a description from 1821. Its water basin is a remnant of the Gabriel Baroque garden and was transferred there when the rose garden was built in the 19th century. In this garden you will find various types of roses such as Damascus roses , centifolia , vinegar roses , Noisette roses and peonies, as well as Turkish poppies and irises .

The current appearance of the small park results from a complete replanting from 1812. The destroyed baroque garden was replaced by an English landscape garden. Before that, Napoleon Bonaparte had some plantings made according to Gabriel's old concept from 1808 in order to be able to present his wife Marie-Louise of Austria with a park that should remind her a little of the palace garden in Schönbrunn . This also included the construction of an arbor covered with climbing roses and pipe flowers , which allowed the imperial couple to get into the forest of Compiègne with dry feet and without being exposed to the sun. Two of the three garden pavilions in the Palladian style that were built by Louis Martin Berthault also date from the Napoleonic era . The conversion of the old French garden into a landscape park was based on his designs . Berthault had 70,000 trees and shrubs planted, including exotic and rare plants. A total of 130 different plant species were used in the redesign. Last changes to the palace park were made under Napoleon III. who had other exotic plants planted in the Small Park , so that today, for example, Lebanon cedars , ornamental cherries, red beeches and tulip trees grow there. The emperor also had various planters with exotic plants set up on the palace terrace, including pomegranate trees , palms , laurel trees and camellias . The tradition of potted plants continues to this day. In order to get a clear view of the mountain Mont Ganelon north of Compiègne from the park , Napoleon III ordered. but also the demolition of parts of the arcade.

The small park flows into the so-called large park ( French grand parc ), a 766 hectare forest, which is criss-crossed by star-shaped paths. It was created at Napoleon's request, but the designs for it came from Ange-Jacques Gabriel. The Great Park merges seamlessly into the Compiègne Forest. All elements of the landscape are connected by a four-kilometer-long aisle, which begins as a visual axis in the middle of the garden facade of the castle and ends on a hill called les Beaux Monts . The carriage ramp laid by Napoleon Bonaparte, which leads from the garden up to the palace terrace, also lies on this central axis. This is bordered by a stone balustrade on which are statues in the ancient style. The first two garden sculptures were erected in the palace gardens in 1811. Under Charles X and Louis-Philippe another 15 statues and vases were added, which Emperor Napoleon III. completed by further sculptures. Ordinary citizens had to wait until September 1870 to admire the works of art, because the park was only opened to the public in the Third Republic. Parts of it have been restored from 1981.

Museums

The castle can look back on a long tradition as a museum. A museum on Khmer culture was established there as early as 1874. This was followed by an archaeological museum in the hall of the guards , in which finds from the Napoleon III. initiated excavations around Compiègne could be seen. In addition, there were temporarily two galleries in the castle. All of these institutions were closed or moved. Today there are three new museums in the building complex.

Museum of the Second Empire

On the ground floor of the Marshal's Wing, an interior museum opened its doors in 1953 , which is dedicated to the Second French Empire. The exhibition had been in preparation for many years, and it had been busy since 1942. The castle's own exhibits were supplemented and enlarged by a collection from Malmaison and a collection from Louis Napoléon Bonaparte . The exhibition is mainly devoted to three topics related to this period: the first Emperor Napoleon III. and his family, the second the court life in the Second Empire and the third the art and culture under Napoleon III. The exhibits include numerous paintings, including Franz Xaver Winterhalter's The Empress Eugénie surrounded by her court ladies . Other painters represented in the exhibition are Édouard Dubufe , Paul Baudry , Eugène Giraud , Joseph Meissonnier and Honoré Daumier . Thomas Couture's sketches for his monumental painting depicting the baptism of the imperial prince can also be seen. In addition to paintings, numerous sculptures are also shown. Among the most important of these are the unfinished marble bust of Napoleon III. by the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux and his bronze statue The Imperial Prince and his dog Nero . The exhibition also shows furniture, wallpaper, and curtains as well as other art objects from that era. One of the 15 rooms is entirely dedicated to Princess Mathilde, Napoleon III's cousin.

Musée de l'Impératrice

There is an exhibition on the former Empress Eugénie de Montijo in five rooms with showcases. Most of the exhibits come from the Ferrand couple's collection, which they bequeathed to the city in 1951. These include many items from the empress's possession from the time of her English exile, but also souvenirs of her son who died in Africa.

National Museum of Voiture et du Tourisme

On the initiative of the Touring Club de France , a museum on all types of transport and its development was opened in 1927 on two floors in the former kitchen wing , in the kitchen courtyard and in the two wings of the building that border it to the north and south. The exhibits include numerous two-wheelers such as a trolley from 1817 and a velocipede by Pierre Michaux from 1861. In the covered kitchen courtyard , a large collection of carriages ( Berliners , coupés , calashes ) can be seen, which are mainly gifts from noble families, For example, the Cossé-Brissacs, the La Rochefoucaulds and the House of Orléans-Braganza , were in the museum or came from the carriage collection of the Musée de Cluny . Among other things, the visitor is presented with the Spanish king's traveling coach from around 1740 and a berline that French President Félix Faure had built for the reception of the tsars in 1896. Another part of the exhibition deals with the automobile and its history. You can see the Mancelle by Amédée Bollée from 1878, a copy of the first French automobile with a Daimler four-stroke engine, the legendary P2D by Panhard & Levassor from June 1891, and the La Jamais Contente by Camille Jenatzy , an over 100 km / h electric record car from 1899. Other special features of the collection are a half-track vehicle from the Citroën company , which was used on an Africa expedition in 1927, and a car from the Delahaye company , which was owned by the Duchess of Uzès , Marie-Thérèse d'Albert de Luynes, belonged. In 1898 she was the first woman in France to drive a car herself. With over 130 different means of transport from the 18th and 19th centuries and around 30 automobiles, the museum is one of the five most important collections of its kind in Europe.

literature

Main literature

- Philip Jodidio (Ed.): Compiègne (= Connaissance des Arts. Special edition) Paris 1991, ISSN 2102-5371 .

- Denis Kilian (Ed.): Musées nationaux du château de Compiègne. Collection guide. Artlys, Versailles 2010, ISBN 978-2-85495-318-3 .

- Jean-Claude Malsy: Compiègne. Le château, le forêt. Nouvelles Éditions Latines , Paris [1973], pp. 2-7, 18-23.

- Jean-Marie Moulin: Guide du musée national du château de Compiègne. Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-7118-2737-2 .

- Jean-Marie Moulin: Le Château de Compiègne. Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-7118-2100-5 .

- Pierre Quentin-Bauchart: Les chroniques du château de Compiègne. Roger, Paris 1911 ( digitized ).

- Cathrin Rummel: France's most beautiful palaces and castles. Travel House Media, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-8342-8944-5 , pp. 51-59.

- Emmanuel Starky: Compiègne royal et impérial. Le palais de Compiegne et son domaine. Grand Palais, Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-7118-5585-8 .

- Emmanuel Starky (Ed.): Le Palais impérial de Compiègne. Musées et Monuments de France, Paris 2008, ISBN 978-2-7118-5483-7 .

- Jean Vatout: Le château de Compiègne. Son histoire et a description. Didier, Paris 1852 ( digitized version ).