Marie-Antoinette of Austria-Lorraine

Marie-Antoinette's signature:

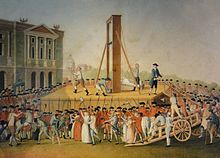

Marie-Antoinette (born November 2, 1755 in Vienna , † October 16, 1793 in Paris ) was born as Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria . By marrying the heir to the throne Ludwig August, she became Dauphine of France on May 16, 1770 . After her husband's accession to the throne as Louis XVI. she was Queen of France and Navarre from May 10, 1774 , after the French Revolution from September 4, 1791 to August 10, 1792 Queen of the French. Initially popular, it became the target of hateful propaganda under the Ancien Régime , directed not only against the efforts of the court, but also against the alliance between France and Austria and against attempts at reform in the spirit of enlightened absolutism . She was executed on the scaffold nine months after her husband .

Life

youth

Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna, as her full baptismal name was, was born on November 2, 1755, the fifteenth child and last daughter of Emperor Franz I of Lorraine (1708–1765) and Maria Theresa of Austria (1717–1780) in Vienna. The difficult birth and the earthquake in Lisbon , which had taken place the day before, were interpreted as bad omen for the further life of the Archduchess, especially since her godparents were the King and Queen of Portugal, represented by Maria Antonia's siblings Joseph (II.) and Maria Anna.

Like the other female family members, the Archduchess had to wear corsets at the age of three , which caused her breathing problems. Early on, she showed a tendency towards restlessness. She often avoided class to disperse and showed no inclination to concentrate or do assignments. But she learned to play the harpsichord and harp . Your singing teacher was Christoph Willibald Gluck .

Marriage to the Dauphin

In order to secure its possessions against the aggressive policies of Frederick II of Prussia , the House of Austria - Lorraine joined forces with the Bourbons : Of the children of the imperial couple, Joseph (II.) Was married to Isabella of Parma in 1760 , and Leopold (II.) In 1765 . with Maria Luisa of Spain , 1768 Maria Carolina with King Ferdinand IV./III. of Naples - Sicily and in 1769 Maria Amalia with Duke Ferdinand I of Parma . In the course of this marriage policy , a marriage between Maria Antonia and the Dauphin Ludwig August was considered at an early stage , which should secure the alliance between Austria and France , which was concluded in 1756 but became unpopular after the lost Seven Years War .

1769 requested King Louis XV. for his grandson and heir to the Archduchess. After the marriage contract was concluded, Maria Theresa analyzed her daughter's education and noticed serious shortcomings. So the girl was subjected to an educational rapid bleaching. The strict Empress Dowager also insisted that she share the bedchamber with her until she left for Paris. Maria Antonia's French teacher praised her friendliness, her intelligence and her musicality, but she was largely uneducated. The laziness, and especially the carelessness of the princess, makes it difficult for him to teach her.

On April 19, 1770, the wedding ceremony took place in Vienna's Augustinian Church by procuration . Two days later, the fourteen-year-old said goodbye to her mother and siblings and started her journey to France with a large entourage . On May 7th , the "handover" took place in a neutral area, an island on the Rhine off Strasbourg . There the girl was separated from her companion and dressed again. Maria Antonia became Marie-Antoinette. In Strasbourg and Zabern she was the guest of Cardinal Rohan , who would later involve her in the collar affair.

The actual wedding took place on May 16 in Versailles . As a conclusion to the wedding celebrations, a festival for the population was held on May 30th on Place Louis XV (now Place de la Concorde ) in Paris. Fireworks caused a panic that led to the death of 139 people - not a good omen for the newly entered marriage.

At the French court

At the French court, the young and inexperienced Marie-Antoinette usually attracted negative attention. The strictest Madame Noailles was assigned to her as the first lady-in-waiting , but Marie-Antoinette felt patronized by the elderly lady and referred to her mostly as Madame l'Étiquette . The princess was alien to French customs and relied almost exclusively on the Austrian ambassador, the Count of Mercy-Argenteau . This was given to her by Maria Theresia as a mentor and at the same time was supposed to keep Maria Theresa up to date. This is how Mercy-Argenteau's famous correspondence came into being, a valuable chronicle of Marie-Antoinette's life from her marriage in 1770 to the death of Maria Theresa in 1780.

In the first three years of their marriage, she was influenced not only by Mercy, but also by that of the king's three unmarried daughters - Adélaïde , Madame Victoire and Madame Sophie . They used the naive and good-natured Dauphine for their various intrigues, which were primarily directed against the king's mistress , who was a persona non grata for the three ladies . Influenced by the so-called aunts, Marie-Antoinette harbored a great aversion to the mistress of Louis XV, Madame Dubarry . Although she had many connections at court, the Dauphine refused to speak to her, and the Dubarry was not allowed to speak to the future queen. Only after the Crown Princess followed her mother's written advice to conform at court (she ignored the king's request, which the court perceived as a scandal), after two years, she spoke to Dubarry the famous words “Il ya bien du monde aujourd” hui à Versailles ”(There are many people in Versailles today). Those were the first and last words the Dauphine addressed to Countess Dubarry.

After Marie-Antoinette got to know Princess Lamballe and had gathered a circle of her own friends, she slowly turned away from the influence of the "aunts", which they thanked her with increasing resentment. The Dauphine began to take advantage of the possibilities of her position and attended balls and the Paris Opera , she also sponsored the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck , her former singing teacher. One of her passions was the Pharo game, where she repeatedly gambled away large sums of money. She spent about 15,000 livres a month . Much of the French were starving and this waste did not add to Marie-Antoinette's popularity.

Queen of France

The accession of the young royal couple to the throne after the death of Louis XV. in May 1774 was greeted enthusiastically. However, her first steps already brought Marie-Antoinette into open conflicts with the anti-Austrian party. So she insisted on the dismissal of the Duke of Aiguillon and did everything in her power to appoint the former Foreign Minister Choiseul , who had to give up his office due to an intrigue of Madame Dubarry. Therefore she had all the enemies of Choiseul and the Austrian alliance against her. The aunts of Louis XVI. called Marie-Antoinette contemptuously l'Autrichienne , "the Austrian". It was a play on words, as it is pronounced almost like l'autre chienne ("the other bitch") in French . Her casual approach to the court etiquette she hated shocked many courtiers, and her penchant for amusement made her seek the company of the king's brother, later King Charles X (1757–1836), and his young and dissolute circle.

Marie-Antoinette was one of the students of Christoph Willibald Gluck, who she protégé at the Paris Opera, in Vienna . In Versailles she took harp lessons from Philipp Joseph Hinner , her harp teacher originally from Wetzlar ("maître de harpe de la rein"). After 1760, harp literature in Paris increased significantly. This could have been particularly favored by her example, including her harp concerts in her salon (see picture).

Marie-Antoinette, however, did not fulfill her main dynastic task - to become the mother of an heir to the throne - for a long time. The public and the court blamed the queen herself for the absence of a male heir for years, who was said to have had an increasing number of affairs in diatribes instead of interest in her husband. From the autumn of 1774, she was also accused of lesbian tendencies in pamphlets . It is uncertain whether the queen actually had any extramarital affairs. In various biographies, the Swedish Count Hans Axel von Fersen is stylized as her lover; but it is unknown how deep the relationship really went.

Her lavish lifestyle - she was interested in fashion issues and extravagant hairstyles - brought her into disrepute, as did her friendly business relationship with the milliner Rose Bertin . Exaggerated reports were circulated about the expenses for her small castle Le Petit Trianon , which she received from Ludwig as a gift in 1774 as a place to relax away from Versailles etiquette. By reducing access to the Petit Trianon to her friends and patrons, she insulted the excluded members of the court.

Marie-Antoinette's friendship with Princess Lamballe lost intensity and their position was increasingly taken over by Countess Polignac . The Countess succeeded in bringing more and more members of her own family to the court and, through Marie-Antoinette's influence, to give them offices and titles, which the Versailles court found simply scandalous. The number of their enemies and envious people grew. Among them were the king's aunts, the Count of Provence , the Duke of Orléans and his followers at the Palais Royal .

During this critical period her brother, Emperor Joseph II , visited France. He left the Queen a memorandum which clearly showed her the dangers of her behavior. Joseph also urged the royal couple to finally address the issue of offspring. In December 1778 - after eight years of marriage and four years on the French throne - the daughter Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte , Madame Royale , was born, who later became Duchess of Angoulême. After the birth of the child, who was not the hoped-for male heir, the queen lived more secluded.

With the death of her mother Maria Theresa on November 29, 1780, Marie-Antoinette lost a strict but prudent adviser. The position of the queen was strengthened by the long-awaited birth of the dauphin Louis-Joseph-Xavier-François on October 22, 1781. It could also have exerted considerable influence on public affairs after the death of the First Minister, the Count of Maurepas .

The influence of the Polignac family now reached another high point. Madame de Polignac succeeded in appointing Calonne General Controller of Finance and succeeded Madame de Guise as governess of the children after the bankruptcy of Prince Guise. On Mercy's advice, she supported the appointment of Loménie de Brienne as controller general; an appointment that was generally approved, but after its failure the queen was charged.

The anecdote from her was circulating that she had replied to the suggestion that the poor could not buy bread: "If they have no bread, then they should eat brioche [pastries]." However, this saying was already used years before Marie- Antoinette's accession to the throne in 1774, quoted by Jean-Jacques Rousseau around 1766. In the sixth book of his autobiography The Confessions , completed in 1770 and published in 1782, there is the passage: “ Je me rappelai le pis-aller d'une grande princesse à qui l'on disait que les paysans n'avaient pas de pain, et qui répondit: Qu'ils mangent de la brioche! »(German:“ At last I remembered the makeshift solution of a great princess, who was said to be the farmers without bread, and she replied: 'Then they should eat brioche!' ”) It could be a wandering anecdote , which already attributed to the first wife of Louis XIV.

How unpopular Marie-Antoinette was was shown in 1785 in a fraud scandal, the so-called collar affair . Marie-Antoinette was not actively involved in this affair, but her way of life made it almost impossible for the people to believe in her innocence.

With her little village near the Petit Trianon , in which she playfully imitated the life of a simple farmer's wife, she snubbed the high nobility as well as the country folk. Marie-Antoinette, however, was often a victim of circumstances that often left her with no choice to act carefully. When she was portrayed in a simple linen dress in 1783, confronted with the eternal allegations of wastefulness, the silk weavers took to the streets and complained that "a queen who dresses so badly is to blame if the silk weavers starve to death".

On the day after All Saints' Day in 1783, Marie-Antoinette suffered another miscarriage (a "false growth") in the third month of her pregnancy, as the Augspurgische Ordinari Post newspaper reported. Marie-Antoinette gave birth to two more children in the following years, on March 27, 1785 Louis-Charles , Duke of Normandy, later Dauphin and by the royalists as Louis XVII. as well as Sophie-Hélène-Béatrice on July 9, 1786, who died eleven months later.

During a visit to the theater shortly after the collar affair, she was booed by the audience - only now did she realize what hatred and hostility towards the ruling house had built up among the people over the months and years. She was now ready to change her lifestyle and forego costly amenities. There were no more games of chance in their salons, minions in Trianon lost their positions. She avoided the theater, balls and receptions. She withdrew to the circle of her family, where she occupied herself with the children, and tried to lead a new, quieter life. However, this insight came too late.

French Revolution

The year 1789 was a turning point in Marie-Antoinette's life. On June 4, 1789, her eldest son died. The poor financial and economic situation in France should be discussed by the Estates General . The French Revolution began with the declaration of the third estate to consider itself a National Assembly . On October 5 and 6, 1789 , the revolutionaries forced the royal family to move from Versailles to Paris to the Tuileries Palace . Since Marie-Antoinette felt helpless and isolated in Paris, she relied on her friends outside France - Mercy, Fersen and Louis-Auguste Le Tonnelier de Breteuil .

On June 20, 1791, the royal family tried to flee abroad. Marie-Antoinette's long-time friend, Count Hans Axel von Fersen, played a leading role in the escape to Varennes . In Varennes the king was recognized and arrested. The royal family was then returned to Paris under guard. On July 25, 1792, the commander-in-chief of the troops allied against France, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg , published the so-called Manifesto of the Duke of Braunschweig at the request of Marie-Antoinette . In this violence including the destruction of Paris was threatened in the event that something happened to the royal family. Thereupon the people stormed the Tuileries on August 10th and brought the royal family to the Temple , a former fortress of the Knights Templar . There the royal family was closely guarded, but there were still opportunities to communicate with the outside world.

The indifference of the king led to the queen taking part in the negotiations. Because of their inexperience and ignorance, as well as insecure information from abroad, it was difficult for them to pursue a clear policy. Her attitude on returning from Varennes had impressed Antoine Barnave , who contacted her on behalf of the Feuillants and the constitutional party.

For about a year she negotiated with Mercy and Emperor Leopold II , her brother. In secret messages she tried to persuade the rulers of Europe to take armed intervention to crush the revolution. Realizing that Barnave's party would soon be powerless against the radical Republicans, her appeals became more urgent. But the negotiations continued. Leopold II died on March 1, 1792, followed by Franz II. Marie-Antoinette feared, not without reason, that the new emperor would not dare to intervene in her favor. Marie-Antoinette's son fell ill while in captivity.

On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI. executed after a trial before the National Convention . Several attempts were made to save her and her children through Marie-Antoinette's friends, including Jarjayes, Toulan, Lepitre and the Baron Baz. Negotiations about her release or an exchange were also held with Danton . Her son had already been taken away from her and she is now being separated from her daughter and from Madame Élisabeth , the king's sister. On August 1, 1793, she was transferred to the Conciergerie prison.

Trial and Execution

On October 14, 1793 the trial against the "widow Capet" (referring to Hugo Capet , the ancestor of the French ruling family) began. Claude Chauveau-Lagarde and Guillaume Alexandre Tronson du Coudray had taken on their defense . They were accused of treason and fornication . Her attitude in the face of Fouquier-Tinville's accusations drew respect from even some of her enemies, and her responses during the long interrogation were clear and thoughtful. The jury unanimously ruled guilty and sentenced her to death .

The execution took place on October 16. At 12 o'clock, Marie-Antoinette was in the Revolution Square, now the Place de la Concorde , beheaded . A drawing by the painter Jacques-Louis David shows the condemned woman on the hangman's cart on her way to the guillotine . He was standing by the window when she was driven past on the street below.

Marie-Antoinette was buried in a mass grave near what is now La Madeleine Church . Today the Chapelle expiatoire commemorates this first burial place . More than 20 years after her death, her body was exhumed - with a garter belt aiding her identification - and Marie-Antoinette was now in the Saint-Denis Cathedral in Saint-Denis (10.3 km north of Paris), the traditional burial place of the French kings, buried at the side of their husbands.

progeny

- Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte (December 19, 1778 - October 19, 1851), Countess of Marnes ⚭ Louis-Antoine , Duke of Angoulême (August 6, 1775 - June 3, 1844)

- Louis-Joseph-Xavier-François (October 22, 1781 - June 4, 1789), Duke of Brittany

- Louis-Charles (March 27, 1785 - June 8, 1795), Duke of Normandy

- Sophie-Hélène-Béatrice (born July 9, 1786 - † June 19, 1787)

In 1787, Marie-Antoinette's favorite painter, Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun , depicted the queen as a mother (picture), Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte on her right shoulder, Louis-Charles in her arms and the Dauphin Louis-Joseph-Xavier-François standing at the cot. The empty cradle symbolizes the late Sophie-Hélène-Béatrice. Originally, the child was also portrayed during his lifetime. After his death the portrait was made anew, now with the empty cradle, to show the queen's mourning.

Historical evaluation

Marie-Antoinette is judged differently by biographers. Some reproach the queen, which was already raised during her lifetime: she negatively influenced Louis XVI, who is often portrayed as weak, and tried behind the scenes to prevent any compromise with the Third Estate. The British historian Eric Hobsbawm describes Marie-Antoinette as a "mindless and irresponsible woman". Albert Soboul , director of the Institute for the History of the French Revolution at the Sorbonne , apostrophized her as "pretty, frivolous and unwise" and accused her of having, together with her husband, incited foreign powers to war against revolutionary France in 1791/92, hoping its defeat would restore their own power.

Stefan Zweig described her in Marie Antoinette - Portrait of a Middle Character in 1932 as an average person without excellent qualities. In his opinion, she was frivolous, rather passive and hardly aware of her responsibility, since she had hardly ever stepped out of her very limited, luxurious world. Zweig also emphasizes that Marie-Antoinette's fall, her sufferings and humiliations made her mature into a responsible and courageous woman.

In her biography Marie-Antoinette, published in 2006, Antonia Fraser paints the picture of a woman who was overwhelmed by the role she was supposed to play and who overlooked the signs of the times. Sofia Coppola used this image as a basis for her 2006 film . She explained: “I knew the usual clichés about Marie-Antoinette and her lifestyle. But I never realized how young she and Louis XVI. really were (at the wedding 14 or 15 years old). Basically, as a teenager, you were responsible for leading France through a very volatile era from an incredibly flamboyant royal court at Versailles. "

ancestors

literature

- Evelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The biography. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-491-96126-2 .

- Antonia Fraser: Marie Antoinette. DVA, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-421-04267-5

- Vincent Cronin: Louis XVI. and Marie-Antoinette. A biography . List, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-548-60591-5

- Silvia Dethlefs: Marie Antoinette, Archduchess of Austria. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 16, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-428-00197-4 , pp. 183-185 ( digitized version ).

- Joan Haslip: Marie Antoinette. A tragic life in stormy times. Piper, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-492-24573-0

- Franz Herre: Marie Antoinette. From the royal throne to the scaffold. Hohenheim, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-89850-118-3

- Évelyne Lever: Marie Antoinette. The secret diary. Amalthea, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-85002-517-9

- Dorothy Moulton-Mayer : Minuet and Marseillaise. The life of Marie-Antoinette, Archduchess of Austria and Queen of France. from Schröder, Hamburg 1969

- Lea Singer : The Austrian whore. 13 conversations about Queen Marie-Antoinette and pornography. dtv, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-423-24454-2

- Antal Szerb : The Queen's Collar. dtv , Munich 2005, ISBN 3-423-13365-1

- Barbara Vinken: The two bodies of Queen Marie-Antoinette . In: Gerhard Johann Lischka (Ed.): Mode - Kult. Wienand, Cologne 2002

- Barbara Vinken: Marie-Antoinette: cult body, rejected and holy. In: semiotics. 27/3, 2005, pp. 269-283

- Friedrich Weissensteiner: The daughters of Maria Theresa. Kremayer & Scheriau, Vienna 1991

- Robert Widl: Marie Antoinette and the French Revolution. Stieglitz, Mühlacker 2001, ISBN 3-7987-0358-2

Movie and TV

- Une Aventure secrète de Marie-Antoinette (F 1910), directed by Camille de Morlhon, with Yvonne Mivval in the leading role

- Marie Antoinette - The life of a queen (D 1922), director: Rudolf Meinert, with Diana Karenne

- Marie-Antoinette (USA 1938), directed by WS Van Dyke , with Norma Shearer

- Marie-Antoinette reine de France (F 1956), directed by Jean Delannoy , with Michèle Morgan

- Caméra explore le temps: La mort de Marie-Antoinette , TV (F 1958), directed by Stellio Lorenzi, Annie Ducaux

- Marie-Antoinette (F 1975) (4 episodes), directed by Guy-André Lefranc, with Geneviève Casile

- La Nuit de l'été (The Night in Summer) , TV (F 1979), director: Jean-Claude Brialy, with Marina Vlady as Marie-Antoinette.

- Lady Oscar - The Roses of Versailles (JAP 1979) (TV anime)

- La Nuit de Varennes (F, IT 1982), directed by Ettore Scola, with Eléonore Hirt as Marie-Antoinette, Harvey Keitel, Hanna Schygulla

- La Révolution française ( The French Revolution ) (F, IT, D, CAN, UK 1989), directed by Robert Enrico, Richard T. Heffron, with Jane Seymour as Marie-Antoinette.

- L'Autrichienne (F 1989), directed by Pierre Granier-Deferre with Ute Lemper as Marie-Antoinette

- Marie Antoinette is niet dood (Marie-Antoinette is not dead) (NL 1996), directed by Irmahaben, with Antje de Boeck

- The Queen's Collar (DVD title), also Das Collier (USA 2001), directed by Charles Shyer, with Joely Richardson and Hilary Swank

- Marie-Antoinette (F 2005), directed by David Grubin

- Marie-Antoinette , TV (CAN, F 2006), directors: Francis Leclerc and Yves Simoneau , with Karine Vanasse

- Marie Antoinette (USA, F, JAP 2006), director: Sofia Coppola , with Kirsten Dunst

- Farewell my queen! (ES, F 2012), directed by Benoît Jacquot , with Diane Kruger

- The last 76 days of Queen Marie-Antoinette , documentary, TV (F 2019), director: Alain Brunard

theatre

- Marie Antoinette (world premiere: Japan 2006), directed by Tamiya Kuriyama

- Marie Antoinette (European premiere: Bremen 2009), director: Tamiya Kuriyama

music

Web links

- Literature by and about Marie-Antoinette of Austria-Lorraine in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Marie-Antoinette of Austria-Lorraine in the German Digital Library

- Marie Antoinette's will (French)

- Video: Marie Antoinette Documentation (2005) by David Grubin (French)

- Hans Conrad Zander : 11/02/1755 - Queen Marie-Antoinette's birthday at WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Individual evidence

- ^ Nancy Plain: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, and the French Revolution. Marshall Cavendish, Singapore 2002, p. 11.

- ↑ a b c Friedrich Weissensteiner: The daughters of Maria Theresa. Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1994

- ^ Michael Stegemann: Composer. Reformer of the old opera. Christoph Willibald Gluck was born 300 years ago , in: Deutschlandradio Kultur , July 2, 2014 ( online )

- ^ Youri Carbonnier: Philippe Joseph Hinner, maître de harpe de Marie-Antoinette, 1755–1784. In: Recherches sur la musique française classique XXIX (1996–1998), pp. 223–237.

- ↑ Riemann Musiklexikon 2012, Vol. 2, p. 329.

- ^ S. Adolphe Jullien: La cour et l'opéra sous Louis XVI. Marie-Antoinette et Sacchini, Salieri, Favart et Gluck . Librairie académique Didier et Cie, Paris 1878, reprinted by Minkoff Reprint, Geneva 1976, ISBN 2-8266-0614-X , p. 325 ff.

- ^ Confessions , livre VI

- ^ In the library of the University of Augsburg , accessed on May 5, 2010

- ↑ Albert Soboul: The Great French Revolution. An outline of their history (1889–1799) . 5th edition. athenäum, 1988, ISBN 3-610-08518-5 , pp. 220 .

- ↑ Jonathan Sperber : Revolutionary Europe 1780-1850. Longman, Harlow 2006, p. 80

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm: European Revolutions. 1789-1848. Parkland, London 2004, p. 121

- ↑ Albert Soboul: The Great French Revolution. An outline of their history (1889–1799) . 5th edition. athenäum, 1988, ISBN 3-610-08518-5 , pp. 74 .

- ↑ Albert Soboul: The Great French Revolution. An outline of their history (1889–1799) . 5th edition. athenäum, 1988, ISBN 3-610-08518-5 , pp. 206 f .

- ^ Stefan Zweig: Marie Antoinette. Portrait of a medium character. Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1932 ( E-Text )

- ^ Review of the film Marie-Antoinette on filmstarts.de with comments by the director

| predecessor | Office | Successor |

|---|---|---|

| Maria Leszczyńska |

Queen of France and Navarre 1774–1793 |

Maria Amalia of Naples-Sicily |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Marie-Antoinette |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia; Austria-Lorraine, Marie-Antoinette von |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Queen of France and Navarre |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 2, 1755 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 16, 1793 |

| Place of death | Paris |