Johan Gadolin

Johan Gadolin (born June 5, 1760 in Åbo ( Turku in Finnish ), † August 15, 1852 in Virmo ( Mynämäki in Finnish )) was a Finnish chemist . In 1794, Gadolin discovered the first chemical element from the group of rare earth metals , yttrium, in the mineral ytterbit , and was one of the first advocates of Lavoisier's theory of combustion in Scandinavia .

childhood and education

Johan Gadolin was born into a Finnish-Swedish family of scholars. His father was a professor of physics and theology at Åbo University . Later he worked as a bishop in this city. Through his educated family, he came into contact with scientific subjects, especially physics and astronomy, in his childhood . His grandfather Johan Browall did a great job as a professor of physics and as a bishop. Through him there were friendly relations between the family and Carl von Linné . Johan Gadolin shaped this environment at an early stage.

After attending school, he began studying mathematics and physics at the Royal Academy of his hometown in 1775, and later switched to the chemistry lectures of Professor Pehr Adrian Gadd, who had held the first chair for chemistry at this university since 1761 . It is the oldest university in Finland. The chemistry lectures he had experienced were too one-sided for him, as they were very much oriented towards practical applications and agriculture. His interests focused on theoretical questions and he found the lectures increasingly unsatisfactory. Therefore, Gadolin moved to Uppsala University in 1779 and attended lectures with Torbern Olof Bergman . Here he also intensified his studies in physics and mathematics.

In the summers when there were no events, he traveled around Sweden to improve his mineralogical and metallurgical knowledge. Gadolin and Carl Wilhelm Scheele met during their studies in Uppsala , and they were friends for a long time. With the support of Bergman, he wrote a dissertation in 1781 on the subject of "De analysi ferri". The following year he obtained his master's degree in philosophy with the subject “De problemate catenario”. Now began his important work on thermodynamics, which he later continued in Åbo (Turku in Finnish) and published in 1784. In 1783 he left Uppsala University and took an extraordinary professorship in his native city.

Scientific work

In his new position at the Royal Academy of Åbo , Gadolin pursued his endeavors to gain further knowledge through an almost two-year study trip to Europe. It began in 1786 and passed through Denmark, Germany, Holland and England. His most important stations included Lüneburg, Helmstedt, the mining area in the Harz Mountains, Göttingen, Amsterdam, London and Dublin. During this trip he gained valuable experience and, above all, information about the new chemical nomenclature. A particularly long lasting relationship arose with the Göttingen chemist and Bergrat Lorenz von Crell . In London he dealt with analytical studies on iron ores and published his findings on this. At the same time, Gadolin expressed his first thoughts on dimensional analysis in chemistry. The chemical industry in England was one of the destinations he visited during his stay.

With his friend, Irish private scholar Richard Kirwan , he made a trip to Ireland, which mainly served mineralogical studies. An article in the chemical journal of his friend Crell reports on the Irish travel impressions.

Gadolin returned to his Finnish homeland with a wealth of experience and in 1788 published a treatise on the new nomenclature in chemistry. It is dedicated to the meritorious work of Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier , Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveau , Antoine François de Fourcroy and Claude-Louis Berthollet . That brought him the attention of this group of people. A more intensive scientific exchange ensued with Berthollet and Guyton de Morveau. His friend Crell wrote to him after his return: "With your talents and knowledge, I would not be surprised that you will make chemistry flourish in Finland."

Now the professional development of Gadolin was consolidated. First appointed as adjunct in 1789, he quickly became a professor. Even in the last years of his teacher Gadd's life, he took over lectures and, after his death in 1787, also the full professorship. On the basis of his rich experience, he changed the course content of the class and is now considered the real founder of scientific chemistry in Finland.

During his trip to Europe he wrote a paper on the theory of phlogistons (1788). At first he assumed the existence of the phlogiston, but was aware of the role of oxygen in combustion . With this essay, Gadolin attempted a mediating approach between the two opinion camps through his own theory. Eventually his concerns about Lavoisier's views subsided and he became the first Scandinavian chemist to join the new teachings on combustion. Logically, Gadolin wrote the first anti-inflammatory chemistry textbook in Swedish, published in 1798 with the title Introduction to Chemistry . It made a decisive contribution to the dissemination of the new knowledge among northern European scientists.

His language skills enabled versatile communication with various important partners in Europe. In addition to his mother tongue Swedish, Gadolin also mastered Latin, German, English, French, Russian and Finnish. Correspondence partners included Joseph Banks , Torbern Olof Bergman, Claude Louis Berthollet, Adair Crawford, Lorenz Florenz Friedrich Crell, Johann Friedrich Gmelin , Louis Bernárd Guyton de Morveau, Richard Kirwan, Martin Heinrich Klaproth , Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and Carl Wilhelm Scheele .

The discovery of yttrium

His best-known scientific contribution as a chemist consists in the analysis of a black mineral from the feldspar quarry of Ytterby on the Swedish island of Resarö , which was operated for the Stockholm porcelain factory. There in 1788 the collector and Swedish artillery officer Carl Axel Arrhenius found a previously unknown black mineral, which was first described by Bengt Reinhold Geijer (1758–1815) and Sven Rinman (1720–1792) and which was later given the name gadolinite. Gadolin received a sample of this mineral and examined it in detail between 1792 and 1793. He described this piece as a red feldspar in which the black, opaque mineral is embedded in a tabular and kidney shape.

The analysis result showed clay , iron oxide and silica as well as a larger proportion (38%) of an unknown oxide . He was not entirely sure about the assessment of his discovery and expressed his concerns in a letter to the secretary of the Swedish Academy of Sciences. The Swedish chemist Anders Gustaf Ekeberg confirmed with his own analyzes in 1797 the results of gadolin and thus the existence of an unknown earth oxide . The element yttrium discovered in this context was later isolated in metallic form by Friedrich Wöhler (1824) and Carl Gustav Mosander (1842).

In Crell's Chemical Annals , gadolin comments on his suspected discovery as follows:

“From these properties one finds that this earth corresponds in many ways with the alum earth; in others, however, with the limestone earth, which also differs from both, as well as from other previously known types of earth. Therefore it seems to deserve a place among the simple earth species, because the experiments made so far do not suggest any composition of others. Now I do not dare to claim such a new invention, because my small supply of black stone did not allow me to pursue the experiments as I wished. In any case, I also think that science should rather win if the several new types of earth, recently described by the separators, could be broken down into simpler parts than if the number of new, simple types of earth were increased even further. "

There were temporarily different views on the assignment of names. Ekeberg named the discovered mineral yttersten and the unknown metal oxide ytter earth . The terms gadolinite and gadolin earth for the chemical substance were proposed by German mineralogists and chemists . Finally a compromise was found. The mineral bears the name gadolinite and the chemical element is called yttrium.

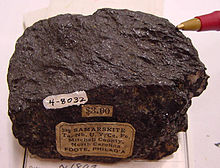

The considerable importance of Gadolin's investigations with this mineral lies in the fact that several element discoveries in the group of rare earths from Scandinavian sites were made as a result. To honor his great merits was the aim of the proposed name for a new element. In 1880, the Swiss chemist Jean Charles Galissard de Marignac discovered a new element during an analytical study of the mineral samarskite (formerly also uranotantalum, yttroilmenite), which was named gadolinium in 1886 by Paul Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran .

When the German chemist Johann Friedrich Gmelin died, Gadolin received the call in 1804 to take over his professorship at the University of Göttingen . But his close connection to his homeland made him refrain from this honorable appointment.

Late years

During his further university work, Gadolin developed theories about chemical proportions and affinities. However, they received little attention due to their limited journalistic dissemination in Central Europe and were suppressed by the work of other scientists. In 1822 he retired. Nevertheless, the scientific work continued by dealing with a systematics in the mineral kingdom Systema fossilium . The basis for this work were the collections of natural materials at the university, which had grown considerably under his responsibility. Unfortunately, it did not receive any major attention after publication.

In 1827 a major fire destroyed the city of Åbo, which also affected the university and large parts of the collections. This event ended Gadolin's active scientific work. The Finnish university was then moved to Helsingfors (now Helsinki ). As a result of this loss, he lived in seclusion on his two estates near Vichtis (now Vihti ) and Virmo (now Mynämäki). He died on August 15, 1852 at the old age of 92.

Achievements and awards

In his home country Finland he profiled the chemistry education according to the latest scientific knowledge and introduced regular practical work and laboratory exercises for the students. At that time, this way of working was not yet common practice in many other European universities.

The mineral gadolinite (discovered by him in 1794) and the element gadolinium are named after him. The name of the asteroid (2638) Gadolin reminds of him and the Finnish astronomer Jacob Gadolin .

Johan Gadolin was a member of:

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences , Stockholm

- Russian Academy of Sciences , Saint Petersburg

- Royal Irish Academy , Dublin

- Member of the Leopoldina since 1797

- Academy of Sciences in Göttingen (since 1804)

Scientific societies

- in Göttingen

- Uppsala

- Moscow (Natural Science Society)

- Marburg (Natural Research Society)

literature

- It. Hjelt / Robert Tigerstedt (ed.): Johan Gadolin 1760–1852 in memoriam . Acta societatis scientiarum Fennicæ Tom. XXXIX., Helsigfors 1910

- Lucien F. Trueb: The chemical elements . Stuttgart, Leipzig (Hirzel) 1996 ISBN 3-7776-0674-X

- Winfried R. Pötsch et al .: Lexicon of important chemists . Leipzig (Bibliograf. Institute) 1988 ISBN 3-323-00185-0 , p. 161

- Theodor Richter: Carl Friedrich Plattner's trial art with the soldering tube or complete instructions for qualitative and quantitative soldering tube examinations . Leipzig (Joh. Ambr. Barth) 1865, 4th ed.

Web links

- Treatise on the history of the discovery of rare earths (chemie-master.de)

- Portraits by Johan Gadolin ( Memento from April 27, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ Rediscovery of the Elements - Yttrium and Johan Gadolin (PDF) There: "In addition to his native Swedish, he also was fluent in Latin, German, English, French, Russian, and Finnish."

- ↑ Crell's Chemical Annals. 1788, Vol. 1, p. 229

- ^ Sven Rinman : Bergwerks-Lexicon , article Pechstein - e). Stockholm 1789 (Swedish)

- ↑ Johan Gadolin: From a black, heavy type of stone from Ytterby quarry in Roslagen in Sweden . in: Crells Chemische Annalen, 1796. IS 313 to 329

- ↑ Edv. Hjelt / Robert Tigerstedt (ed.): Johan Gadolin 1760-1852 in memoriam. Acta societatis scientiarum Fennicæ Tom. XXXIX., Helsigfors 1910, p. VII

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 88.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gadolin, Johan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Finnish chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 5, 1760 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Turku |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 15, 1852 |

| Place of death | Mynämäki |