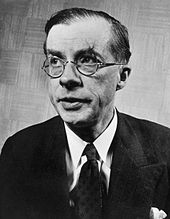

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (born June 22, 1887 in London , † February 14, 1975 in London ) was a British biologist , philosopher and writer. His early observations of behavior on loons and herons were among the first precise studies in behavioral research that paved the way for the work of Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen , among others . Huxley was a humanist and a well-known thought leader in eugenics and atheism . As the first UNESCO Director- General , he made a significant contribution to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights .

Life

Julian Huxley was the eldest son of Leonard Huxley and his first wife Julia Frances Arnold and the grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley . He was educated at Eton and studied zoology at Oxford . From 1910 to 1912 he worked as a lecturer in zoology at Balliol College , from 1912 to 1916 he taught at the Rice Institute in Houston (Texas). In 1919 he returned to Oxford, but then became a professor (1925-1927) and honorary professor (1927-1935) at King's College London . He then served as Vice President (1937–1944) and President of the Eugenics Society (1959–1962) and as Secretary General of the London Zoological Society (1935–42).

In 1934 he directed the short film The Private Life of the Gannets , a documentary about gannets that on a small rocky island off the coast of Wales to live. The film won an Oscar for best short film (a film role) in 1937.

Julian Huxley played an important role in the founding phase of UNESCO and was the organization's first director general from 1946 to 1948. Furthermore, the founding of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) goes back to an initiative by Huxley. Huxley was the first president of the IHEU, which is now an association of over 170 humanist and secular organizations. Julian Huxley was awarded the Kalinga Prize for Popularizing Science in 1953 .

He was also an important exponent of eugenics . From 1937 to 1944 and 1959 to 1962 he held a leading position on the board of directors of the British Eugenics Society , now the Galton Institute .

In 1960, Huxley was a consultant to UNESCO on wildlife conservation issues in East Africa; he published some newspaper articles in the British weekly newspaper The Observer , in which he drew attention to the nature and habitat destruction of wild animals in Africa. The public attention that his texts received gave rise to the idea and the publicity required to found the WWF in spring 1961.

family

Julian Huxley was the brother of Aldous Huxley (writer) and Andrew Fielding Huxley (biophysicist, Nobel Prize in Medicine ) and the grandson of Thomas Henry Huxley (biologist; nickname Darwin's Bulldog ), who had played a major role in the implementation of the teachings of Darwin.

Work and impact history

Huxley coined the idea of evolutionary humanism and "atheism in the name of reason": "God is a man-made hypothesis in an attempt to cope with the problem of existence." The Germany-based Giordano Bruno Foundation explicitly refers to Huxley's ideas and wants to promote, develop and disseminate them.

The so-called aluminum hat goes back to the science fiction story The Tissue-Culture King .

Awards

In 1938 he was elected as a member (" Fellow ") in the Royal Society , which in 1956 awarded him the Darwin Medal . In 1948 he became a corresponding member of the Académie des sciences . In 1958 he was beaten to the Knight Bachelor . In 1961, Huxley was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

Works

- The individual in the animal kingdom (1911)

- The courtship habits of the Great Crested Grebe (1914)

- Essays of a Biologist (1923)

- The stream of life (1926)

- Animal biology (with John Burdon Sanderson Haldane , 1927)

- Religion without revelation (1927, revised new edition 1957)

- The tissue-culture king (1927)

- Ants (1929)

- Bird-watching and bird behavior (1930)

- What dare I think? (1931)

- The captive shrew and other poems (1932)

- The science of life (with HG Wells and his son George Philip Wells , 1931)

- Problems of relative growth (1932)

- A scientist among the Soviets (1932)

- Scientific research and social needs (1934)

- Elements of experimental embryology (with Gavin de Beer , 1934)

- An introduction to science (with EN Andrade , 1934)

- Thomas Huxley's diary of the voyage of HMS Rattlesnake (1935)

- We Europeans. A survey of racial problems (with Alfred C. Haddon , 1935)

- Animal language (1938)

- The living thoughts of Darwin (1939)

- The new systematics (1940)

- The uniqueness of man (1941)

- Evolution: the modern synthesis (1942, revised new edition 1963)

- Democracy marches (1941) (German: Demokratie marschiert (1942))

- Evolutionary ethics (1943)

- TVA: Adventure in planning (1944)

- On living in a revolution (1944)

- Touchstone for ethics (1947)

- Man in the modern world (1947), essays selected from The uniqueness of man (1941) and On living in a revolution (1944) (German: Der Mensch in der moderne Welt (1950))

- Evolution in action (1953) (German: Entfaltung des Lebens (1954))

- From an Antique Land: Ancient and Modern in the Middle East (1954) (German: The desert and the old gods (1956))

- Kingdom of the beasts (with W. Suschitzky, 1956) (German: Das Reich der Tiere (1956))

- The story of evolution (1958)

- Biological aspects of cancer (1957) (German: cancer in biological view (1960))

- The humanist frame (as editor, 1961) (German: The evolutionary humanism: 10 essays on the main ideas and problems (1964))

- Essays of a humanist (1964) (new edition 1992 with the title: Evolutionary Humanism , ISBN 0-87975-778-7 ) (German: I see the future man: nature and new humanism (1965))

- The wonderful world of evolution (1969) (German: Wonderful world of evolution: The development of life from protozoan to human (1970))

- Memories (1970)

- Memories II (1973) (German: A life for the future: memories (1974/1981))

- The Atlas of World Wildlife (1973) (German: Großer Atlas des Tierleben . Corvus Verlag, Berlin (1974))

Web links

- Literature by and about Julian Huxley in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Julian Huxley in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Julian Huxley in the Munzinger archive ( beginning of article freely accessible)

- https://www. britica.com/biography/Julian-Huxley

Individual evidence

- ^ Julian Huxley | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved January 4, 2019 .

- ^ Paul Weindling: 'Julian Huxley and the Continuity of Eugenics in Twentieth-Century Britain' . In: Journal of modern European history . tape 10 , no. 4 , November 1, 2012, p. 480-499 , PMC 4366572 (free full text).

- ^ History - The Galton Institute. Retrieved January 4, 2019 (American English).

- ^ Kate Kellaway: How the Observer brought the WWF into being | Feature . In: The Guardian . November 7, 2010, ISSN 0261-3077 ( theguardian.com [accessed January 4, 2019]).

- ↑ Conspiracy theories: To save the honor of the aluminum hat , Zeit Online , June 11, 2017, accessed on October 19, 2019

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Huxley, Julian |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Huxley, Sir Julian Sorell |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British biologist, philosopher and writer; first Director General of UNESCO |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 22, 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 14, 1975 |

| Place of death | London |