Karl Caspar (pilot)

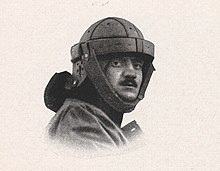

Karl Christian Maximilian Caspar (born August 4, 1883 in Netra ( Hessen-Nassau ), † June 2, 1954 in Frankfurt-Höchst ) was a German pilot , aircraft manufacturer and lawyer . He gained notoriety in the 1920s in particular for the types of aircraft developed and built by the Caspar factories . As a pilot who passed his exam before the First World War , he is one of the Old Eagles .

Life

Childhood and youth

Karl Caspar came as the fifth and youngest child of from Wroclaw coming, the district court employed Netra court secretary Wilhelm Ernst Maximilian and his wife, who from Kassel originating Anna Katharina Ida, born Gruber, to the world. In addition to his father, he was named after his godfather on his mother's side, the sculptor and architect Karl Christian Gruber (1856–1934). His siblings were Johannes Heinrich Kurt (1876–?), Julius Walter (1878–1881) and the twin sisters Klara Melida Emilie (1879–1881) and Erna Emilie Marie (1879–1944).

In 1890 the family moved to Kassel, where Caspar attended the Royal Wilhelms-Gymnasium . After graduating from high school, he began studying law in Marburg . There he became a member of the Alemannia fraternity . In 1905 he interrupted his studies and went as a one-year volunteer to the protection force in German South West Africa . There he took part in the suppression of the Herero uprising as a rider in the replacement company of the 1st Field Regiment and received the 2nd Class Military Medal of Honor on March 20, 1906. Serious typhoid fever forced him to return to Germany that same year. Caspar became lieutenant in the reserve in the "Freiherr von Manteuffel" (Rhenish) No. 5 dragoon regiment in Hofgeismar . Back in Germany he completed his studies in Marburg and Tübingen and passed the legal trainee examination in Kassel . After his initial training in Karlshafen , he was transferred to the Berlin Court District as a court trainee .

Pilot and first company

In Johannisthal he came into contact with aviation, which was just developing, took flight lessons from Paul Lange and on March 27, 1911 received the pilot's license No. 77. Shortly afterwards, Caspar had an accident in a crash near Magdeburg . Recovered, he took part in the autumn flight week of 1911 and successfully completed a five-hour continuous flight, for which he received 1,334 ℳ . Shortly afterwards, Caspar opened a flight school in Wandsbek called the Central Aviation School. He hired his former flight instructor Paul Lange as an instructor. As early as November 1, 1911, the company was renamed Hanseatische Flugzeugwerke Karl Caspar and, in addition to training in flying, began manufacturing pigeons under license from the Gothaer Waggonfabrik .

Caspar continued to take part in flight events. On June 19, 1912 he was able to set a national altitude record of 3,240 m and at the Nordmarkenflug he won the altitude award endowed with 24 2,400. He received further prize money in 1912 at the Kiel Grand Prix (920.41), the flight around Berlin (8,614) and the Krupp flight week (14,546). During Caspar's subsequent stay in Sweden, the hall of his factory was destroyed by fire on August 9, 1912. Three pigeons in it, one of them still under construction, also fell victim to the flames. The damage amounted to ℳ 65,473.

First World War

Caspar took the opportunity and relocated his business to Fuhlsbüttel , where he also opened the Hanseatic flight school in 1914, where Friedrich Christiansen, among others , acquired his flight license on March 27, 1914. After the outbreak of the First World War, Caspar was called up as a lieutenant in the reserve for Field Aviation Department 9 . There he flew over the English Channel in a Gotha pigeon together with his observer Lieutenant Werner Roos on October 25, 1914 and dropped a 10 kg bomb at Dover , the first to fall on Great Britain during the war, which attracted him some media attention brought in.

During his service, Caspar sold the Hanseatische Flugzeugwerke to the Italian financier Camillo Castiglioni in December 1914 with the condition that he had the right to repurchase if he had left the military by January 1917. In September 1915 the company was merged with other Castiglionis companies to form the Hansa and Brandenburgische Flugzeugwerke AG . In 1917 Caspar made use of his buyback right, bought back his former factory in Fuhlsbüttel and reopened it with a capital of ℳ 1.5 million. Walther Lissauer acted as operations manager. In the further course of the war, fighter reconnaissance aircraft of the type Albatros C.III and later G.III bombers were built there under license and the Caspar flight school was operated.

Weimar Republic

In September 1918 Caspar acquired by Dutchman Anthony Fokker whose Flugzeugwerft on the Priwall in Travemünde , but had to go to war, the production of aircraft to give up, since the Entente had to build prohibited aircraft in the German Empire, and to the production of other products such Grammophon boxes restrict. Caspar therefore closed his factory in Fuhlsbüttel in 1919 and ceded the premises to the Hamburg Senate by April 9, 1920 for ℳ 1,550,000 . At the same time, the Travemünder Werft was renamed Caspar-Werke GmbH . Friedrich Christiansen was appointed as technical director, who recruited Ernst Heinkel as a designer around 1920/1921 , who is also said to have worked as director, which Heinkel later denied. Under the strictest secrecy and circumventing the aircraft construction ban, the two submarine aircraft U 1 and U 2 and, for Sweden, the S I sea reconnaissance aircraft were built on behalf of the USA and Japan .

Karl Caspar received in 1921 from the Technical University of Aachen , the dignity of a Dr.-Ing. e. H. awarded and received his doctorate in the following year with a thesis on aviation law for Dr. jur.

Surprisingly for Caspar, Heinkel left the Travemünde company in October 1922 and set up his own business in Warnemünde . When he left, he recruited a number of Caspar's employees, including the designer Karl Schwärzler. This severely impaired Caspar's relationship with Heinkel and prompted him to file a lawsuit against him for theft of construction plans, which Heinkel was able to win. Caspar's new chief designer was Ernst von Loessl, who was followed by Karl Theiss in 1925, then Reinhold Mewes and, in the summer of 1927, Hans Hermann. Although the company developed 28 different types in the following years, Karl Caspar was no longer a great success as an entrepreneur. In April 1928, the Caspar Works in Travemünde had to close and were taken over by the See Trial Center. After that, Karl Caspar no longer appeared as an aircraft manufacturer and lived in Sindlingen until his death .

After his death, Caspar was buried in the Ohlsdorf cemetery at the instigation of the traditional “Alte Adler” community in Hamburg, his first place of work as an aircraft manufacturer .

literature

- Bodo Dirschauer: Lübeck aviation history. Aircraft construction on the Priwall and in Lübeck from 1914 to 1934 . Steintor, Lübeck 1995, ISBN 3-9801506-1-5 , p. 61 ff .

- Wolfgang Wagner: German air traffic. The pioneering years 1919–1925 . In: German aviation . Bernard & Graefe, Koblenz 1987, ISBN 3-7637-5274-9 , pp. 145 ff .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Birth certificate no. 51, Netra registry office, secondary register of birth, 1883 (HStAM Best. 923, no. 4429). (JPG; 275 kB) In: Hessian birth, marriage and death registers. Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg, accessed on August 15, 2018 .

- ↑ Death certificate no. 452, registry office Höchst secondary death register 1954 (HStAMR order 903 no. 987). (JPG; 330 kB) In: Hessian birth, marriage and death registers. Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg, accessed on August 15, 2018 .

- ^ Imperial protection troops. Protection force for South West Africa. AKO of March 20, 1906 . In: Colonial Department of the Foreign Office . (Ed.): Deutsches Kolonialblatt . 17th year, no. 7 . Ernst Siegfried Mittler and Son, Berlin April 1, 1906, personal details, p. 184–189 , here p. 187 ( full text in the Google book search [accessed on August 15, 2018]).

- ^ Richard Weber: Hessen and the aviation . In: Hessenland . Hessisches Heimatblatt; Journal for Hessian history, folk and local studies, literature and art. 26th year, no. 1 . Friedr. Scheel, Kassel January 1912, p. 8 ( ORKA - Open Repository Kassel [PDF; 45.8 MB ; accessed on August 15, 2018]).

- ^ Jörg Mückler: German bombers in the First World War . Motorbuch, Stuttgart 2017, ISBN 978-3-613-03952-0 , p. 16 .

- ^ Volker Koos: Ernst Heinkel. From the biplane to the jet engine . Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2007, ISBN 978-3-7688-1906-0 , p. 26 .

- ^ Koos, p. 52

- ^ Helmut Stützer: The German military aircraft 1919–1934 . E. S. Mittler & Sohn, Herford 1984, ISBN 3-8132-0184-8 , p. 114 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Caspar, Karl |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Caspar, Karl Christian Maximilian |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German pilot, aircraft manufacturer and lawyer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th August 1883 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Netra , Hessen-Nassau |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 2, 1954 |

| Place of death | Frankfurt-Höchst |