Peterborough Cathedral

The Cathedral of Peterborough , official: The Cathedral Church of St Peter , is due to its three-part facade and consistent asymmetry one of the most unusual medieval cathedrals in Britain. It is dedicated to Saints Simon Peter , Paul of Tarsus and Andrew , the three of whom dominate the three-part facade. The cathedral shows the full-blown, secure Norman-Romanesque style in the architecture of England, comparable to Ely Cathedral .

history

Anglo-Saxon origins

The first church on this site was that of Medeshamstede Abbey , founded by King Peada of Mercia in 655 as one of the first Christian centers in England. The monastic settlement was destroyed by the Vikings around 870 . During the monastic renewal in the middle of the 10th century (which also saw the rebuilding of Ely Cathedral and Ramsey Abbey ), a Benedictine abbey was established , financially endowed in 966 by Æthelwold , Bishop of Winchester . The church and monastery were dedicated to Peter, which is why the settlement that developed around the abbey was eventually named Peterborough. The monastic community was presented again in 972 by Dunstan , Archbishop of Canterbury .

The Anglo-Saxon monastery was damaged in the fighting between the Normans and Hereward the Wake , but it was repaired. In a fire accident in 1116 , however, it was destroyed again (see: Peterborough Chronicle ). Only a small remainder of the church remained by the south transept; however, several important artifacts, including the 'Hedda Stone', were found.

The Norman new building

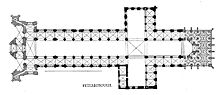

The fire in 1116 made it necessary to erect the new building, which was executed in the Norman style (1118 to 1238) as a three-aisled nave with ten bays , an east transept with only one east aisle and a crossing tower .

The work began under Abbot John de Sais in 1118 as an abbey church. The church only became a cathedral in 1541. A first consecration took place around 1140/43 with the completion of the choir. Of the three-aisled choir, only the middle one has survived from the original three apses.

Next, the transept was built in 1155–1177. Then the work in the nave continued under Abbot Benedict 1177-1194. By 1193, the buildings were completed to the west end of the ship, including the central tower and the ship's painted wooden ceiling. This wooden ceiling, which was completed between 1230 and 1250, has been preserved; it is unique in Britain and one of four such blankets in all of Europe (the rest are in St. Martin in Zillis in Switzerland, in St. Michael in Hildesheim in Germany and Dädesjö in Sweden, but all of them are less than half as long like that of Peterborough). The ceiling was repainted twice, in 1745 and 1834, but still shows the character and style of the original.

The longhouse does not have the dynamic structure of Durham or Ely , but offers a ten-part, somewhat monotonous sequence. For this, the wall openings have been increased further, the room appears more light-filled and thus offers a transition to Gothic , to which the late Gothic enlargement of the windows contributes a lot. The completed church was consecrated in 1238 by Robert Grosseteste , Bishop of Lincoln , to whose diocese Peterborough then belonged.

The nave shows - similar to Durham - a three-part elevation with an arcade zone, a mezzanine floor and an upper arcade with a walkway in the thick wall. The three floors are almost equivalent in size. The arcade zone shows a barely noticeable change of pillars and columns. The wooden ceiling from around 1220 has been preserved. The cornices separating the floors lead over the narrow services. And so, compared to the earlier Norman buildings, the vertical structure takes a back seat and long “stripes” determine the image of the wall over ten yokes on three floors. The rod-like services were not added with a view to a vault, but exclusively as a plastic structure. This brings a new kind of "thought" into the former Norman architecture. The walls look like wide-span grids, the wall appears as an ornament as a whole. And as long as the English cathedrals do without vaults, this impression is reinforced. Later the vault will have a decisive influence on the appearance of the room. By dispensing with a stone vault, it was possible to give the end faces of the transept arms (north transept arm!) The same elevation as the nave, i.e. three rows of windows above a base zone, so that the wall is almost completely divided. And because both upper floors have walkways or galleries, it was possible to walk around the entire building on these two levels.

The central nave was and is flat roofed, the side aisles have ribbed vaults. There the wall-side plinth panels show crossed, at the same time penetrating round arches (“ interlacing ” or “ intersecting arcading ”). This form of decoration comes from book illumination and is particularly used in Norman architecture. Here too, the windows in the side aisles are enlarged in the late Gothic style.

The two west bays of the nave and the west transept were added after 1175. The height of the central nave is only surpassed by Ely. The windows were enlarged in the late Gothic.

A western transept was added in 1193–1200. Of the towers above the arms, however, only the northern one was expanded.

The exterior shows a rich, lined up area structure with varied blind arcades that connect the window openings with one another.

The Gothic conversions

The west facade was built in 1201–22: the west wall and the facade form a large, arched vestibule, a portico, which is divided by three huge pointed arch portals. The uniqueness of this facade solution is underlined by the fact that the middle portal is narrower than the one on the side ('English-enigmatic'). The master builder divided the walls within the arched openings into three storeys - like the elevation of a long house. All wall surfaces are richly decorated with various types of blinds, with figure niches, quatrefoils, rosettes, etc. Schäfke speaks of "one of the most exciting Gothic facades ever built".

The Norman tower was rebuilt around 1350/80 in the decorated style , its main beams have been preserved.

In 1370 a small porch was placed in front of the Romanesque façade, which "obscures" the impression of the façade even more in comparison to continental conditions.

The renovation of the choir

1483–1500 the choir was rebuilt . The only remaining former central apse is backed by a retro choir with a fan vault in Perpendicular style (" New building "). The design perhaps comes from John Wastell, the architect of the chapel of King's College in Cambridge and the Bell Harry Tower of Canterbury Cathedral .

For this purpose, the ground floor of the Romanesque choir wall was broken through and the windows were greatly enlarged, creating a unique picture. The former outer wall is now a retaining wall designed with large arched openings, which offers numerous views of the windows of the new choir. This retro choir itself, the “New Building”, has “one of the most beautiful examples of the fully developed fan vault”. No church on the mainland offers anything like it.

Tudor

The abbey's relics included the (presumed) arm of Saint Oswald of Northumbria , which was probably lost from the chapel during the Protestant Reform although it was guarded, as well as items belonging to Thomas Becket , owned by Benedict, Prior of Canterbury Cathedral and Eyewitness to Becker's murder, brought from Canterbury when he was made Abbot of Peterborough. In 1541 , after the monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII , the relics were lost. The church, on the other hand, survived political developments because it became the cathedral of the new Peterborough diocese - presumably also because Catherine of Aragón , Henry's first wife, was buried here in 1536 . The tomb still exists and bears the inscription "Katharine Queen of England", a title that she was denied at the time of her death. On July 31, 1587 , the body of the Scottish Queen Maria Stuart was also buried here after she had been executed at the nearby Fotheringhay Castle . On the orders of her son, King James I , she was reburied at Westminster Abbey in September 1612 .

From the civil war to the present

The cathedral was devastated in 1643 during the English Civil War . Almost the entire stained glass was destroyed as well as the medieval choir stalls, the high altar, the reredos , the monastery and the Lady Chapel were demolished, and all monuments in the cathedral were damaged or destroyed.

Some of the damage was repaired in the 17th or 18th centuries . Extensive repairs began in 1883 , with the inner columns, central tower, choir and western facade being completely renewed. The new hand-carved choir stalls, the cathedra , the pulpit in the choir, the marble floor and the high altar were added. In 1884 the crossing tower was renewed.

In July 2006 a new restoration project began; the construction progress can be followed with a webcam.

organ

The organ was built in 1930 by the organ builders Norman & Beard in an existing organ case from 1904. The case was designed by the organ builder Hill. In 1980 the instrument was reorganized by the organ building company Harrison & Harrison (Durham) and the existing pipe material restored and the disposition expanded. After the fire in 2002, the instrument was first dismantled and stored, then restored in 2004–2005 and placed back in the cathedral. The instrument has 87 stops on four manuals and a pedal. The actions are electro-pneumatic.

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

literature

- Ernst Adam: Pre-Romanesque and Romanesque. Frankfurt 1968, pp. 116-117;

- Harry Batsford, Charles Fry: The Cathedrals of England , 7th Edition, BT Batsford Ltd., London 1948

- Marcel Durliat : Romanesque Art. Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 1983. p. 498;

- Alain Erlande-Brandenburg : Gothic Art. Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 1984, p. 547, color plate 29;

- Martin Hürlimann: English cathedrals . Zurich 1948

- Werner Schäfke : English cathedrals. A journey through the highlights of English architecture from 1066 to the present day. Cologne 1983, (DuMont Art Travel Guide), pp. 134–141, figs. 39,41,42;

- Wim Swaan: The great cathedrals. Cologne 1969, p. 196, figs. 224–229;

Individual evidence

- ^ Harry Batsford, Charles Fry: The Cathedrals of England , p. 71

- ^ Adam, p. 116

- ^ Durliat, p. 499

- ↑ Hürlimann, p. 21

- ↑ Hürlimann, p. 21

- ↑ Schäfke, p. 134

- ↑ Hürlimann, p. 21

- ↑ For more information on organ (English)

See also

Web links

- Peterborough Cathedral The website of the cathedral with a link to the webcam

- The Cathedral Church of Peterborough , by WD Sweeting, on Project Gutenberg

- Bill Thayers (University of Chicago) website

- Peterborough Cathedral on Skyscrapernews.com

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace Peterborough Cathedral Pages photos

Coordinates: 52 ° 34 ′ 22 " N , 0 ° 14 ′ 23" W.