Molana Monastery

The Molana Monastery ( Irish Mainistir Mhaolanfaidh , English Molana Priory ) was founded in the 6th century by Máel Anfaid near the south coast of Ireland in the Diocese of Waterford and Lismore on an island in the Blackwater River . The monastery achieved special importance through the co-publication of the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis in the 8th century. In the 12th century, the Augustinian rule was adopted as part of a re-establishment and the monastery thus became a priory . During the entire active time of the monastery, one focus was on nursing and caring for the poor. The Reformation led to the abolition of the monastery in 1541; since then the facility has been privately owned. It has been in ruins since the 18th century at the latest, so that only ruins can be seen today.

Name of the monastery

The Irish name of the island is Dairinis , which can be translated as "oak island". In the text sources from the early Middle Ages, this name is also used for the monastery. However, since there was another monastery island with this name in Wexford , the name of the founder Máel Anfaid was added if necessary, for example in the genitive form Dairini's Mailanfaid in a text from the 9th century. Later the old Irish island name was dropped and the name of the founder was taken over. For example, the name Insula Moelanfyd can be found in a document from 1267. This became the current Irish name Mainistir Mhaolanfaidh . The Irish name was later Anglicized to Molana .

Although the monastery became a priory after it was re-founded in the 12th century and never received the rank of abbey , the monastery was and is often called Molana Abbey , and accordingly abbots instead of priors are often used.

Geographical location

The monastery is located on a former river island of the Blackwater River, which was connected to the mainland in 1806 by building two dams on the west side. The site is just a few miles from the estuary and natural harbor of Youghal on Ireland's south coast . Access to the lake was of great importance in the early Middle Ages and was used intensively to establish contacts with other monasteries in Ireland and in Brittany that were accessible via lake and river routes . According to some traditions, a sea voyage between southern Ireland and Brittany was possible in three days and nights in early Christian times. Used here came Curraghs that were sufficiently seaworthy.

history

Early Christian time

The monastery was founded by Máel Anfaid in the 6th century. Little is known about the founder, who is also known as the abbot. There is also the hypothesis that Máel Anfaid lived until the 7th century, as a small legend of saints has come down about him, according to which he learns that Molua mac Ocha has died. Since in the contemporary annals the year of death of Molua with 608 is handed down quite reliably, this would mean that Máel Anfaid lived at least until 608.

Fachnan Mongach has been handed down as one of the other abbots of the second half of the 6th century. He also founded the episcopal see at Ross Carbery and became its first bishop . At the beginning of the 7th century, the monastery was among the first in Ireland to follow the Roman calculation of the date of Easter .

In the 8th century the church reform movement Célí Dé emerged in Ireland , which rejected the increasing secularization of the churches and monasteries, paid attention to strict asceticism and especially turned to the poor and the sick. Fer-dá-chrích, abbot of Molana Monastery until his death in 748, was one of the members of this movement, and there is even evidence to suggest that Máel-Rúain, abbot of Tallaght, was the leading force in this movement , could previously have been a pupil of Fer-dá-chrích. It is even believed, based on additional evidence, that the reform movement originated in the monasteries of Molana, Daire Eidnech, and Lismore , all of which were quite close to one another within the boundaries of what are now Counties of Waterford and Tipperary . As part of this reform movement, the monk Rubin, in collaboration with the Ionian monk Cú Chuimne at the beginning of the 8th century, put together the most important canonical collection of the early Middle Ages with the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis in the Monastery of Molana , which, thanks to the close contacts with Brittany, quickly spread throughout Western Europe should spread. Rubin died in 726.

The hibernensis is an indication that an extensive library must have been available to the creators. In addition to the Vulgate , Greek, African and Gallic council resolutions are cited in the Hibernensis . The Statuta ecclesiae antiqua and the papal decretals were also known to the authors . Exegetical writings , among others by Origen , Hieronymus , Augustine , Isidore , Gregory I and Gregor von Nazianz , were also cited.

Although, as with many other Irish monasteries, Molana can be assumed to have been the victim of raids by Vikings, no such attacks are recorded. In particular, the exposed location near the mouth of the Blackwater makes this very likely. For example, the monastery at Lismore, which was further up the river, was sacked by the Vikings in 833 and later sacked in 883. However, the presence of the Vikings was not limited to raids. It is likely that the Vikings settled permanently in nearby Youghal as early as the 9th century. As an entry in the annals shows, there was even a heavy battle between two rival Viking parties in the immediate vicinity of the monastery on the western bank of the Blackwater in 945.

Adoption of the Augustinian rule

Regular canons, as opposed to monks, only found in the 11th century under Leo IX. Support who saw this as a way to urgently needed reforms on the European continent. In Ireland regular canons were introduced under the rule of Augustine by Malachias , probably as early as 1134 under the direction of Imar Ua h-Aedacháin in Armagh . The adoption of standardized rules, such as those of Augustine or Benedict , was recommended in 1139 at the second Lateran Council . Since this coincided closely with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland, it is not always clear whether the takeover in individual cases occurred as part of the Irish reform movement or because of the support of the invaders. This also applies to the Molana Monastery.

1170 landed near the monastery of Raymond FitzGerald , who was sent to Ireland by Strongbow , military leader on the Leinster campaign from 1169–1171 under Henry II . After taking the monastery, he seems to have made friends with the monks and to have appreciated the associated hospital. According to tradition, Raymond FitzGerald is considered the new founder. Accordingly, it is also assumed that Raymond FitzGerald was buried in the monastery. However, this has not been reliably proven.

The surviving correspondence with Rome shows that some protracted legal disputes over land began in the 14th century. Later, in 1450, Prior John Makenneri was charged by Donald O'Sullivan, an official in the Diocese of Ardfert . In 1462 the monastery was structurally in poor condition, which is why indulgences were granted to those who visited the monastery and gave alms. Nevertheless, as it was reported in the correspondence with Rome, there were still a large number of monks and the sick and needy were cared for. A year later, Prior Thady O'Morrissey was recalled to Waterford Priory, after which Maurice O'Ronan illegally gained control of the monastery for two years. This only ended when Pope Paul II appointed Donald Obreyn as prior. Later, in 1475, it was reported that the monastery was still impoverished, but the religious life of the canons had improved.

Reformation and modern times

During the Reformation, all of the monasteries under the rule of Henry VIII (1491–1547) were dissolved and assessed; this happened at Molana monastery in 1541. According to the report of the appraisal, there was a church, the cloister , farm and residential buildings and everything that was necessary for the operation of agriculture. The monastery included 380 acres of land, three weirs for catching salmon , a watermill and four parishes. The property would have been valued at £ 26 and 15 shillings in peacetime . However, since ongoing rebellions made the land impossible to use, the estimated value was reduced to 72 shillings.

On December 21, 1550, the monastery fell as a fief to James Fitzgerald, the 14th Earl of Desmond; he allowed the monastic life to continue. In 1575 the property went back to the English crown because of the Desmond rebellions and was awarded by it in the same year as a fief to John Thickpenny from Youghal. In the accompanying document from November 24, 1577, which was written a little later, there is a further list of the possessions. Lands in Templemichael, Kilnicannanagh, Donmone and Deskartie were named here. Patrick Power (1862-1951), who worked as a priest in County Waterford all his life intensively with the regional church history, identified Deskartie as a piece of land near Ardmore . Kilnicannagh, Patrick Power suspected, could be Ballinatray's land or a typo for Kilcockan. In addition, two other river islands, which are no longer known today, were named, which probably later became part of land reclamation measures near Youghal.

From 1580 there is a report of English troops who visited the orphaned monastic island as part of the Desmond rebellions and on this occasion desecrated the monastery and, among other things, burned a portrait of the monastery founder, Máel Anfaid. According to the report, the arsonist became insane immediately afterwards and died three days later.

John Thickpenny died in the winter of 1585/86, after which his widow Anne Thickpenny tried to take over the fief. However, Sir Walter Raleigh anticipated this, because the fief was awarded to him by Elizabeth I on July 25, 1587 . After his conviction on November 17, 1603, his property including the Molana Monastery was confiscated and then reassigned as a fief to Sir Richard Boyle. After the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh on October 29, 1619 Sir Richard Boyle succeeded in acquiring the entire previous lands of Raleigh in the counties of Cork and Waterford cheaply; Boyle was raised a little later to the Earl of Cork.

As early as 1600 the buildings were so overgrown with ivy that it was almost impossible to examine the architectural subtleties. Accordingly, the facility slowly fell into ruin. After a sister Richard Boyle married into the Smyth family, the monastery came into their own by inheritance; in 1795 she built a mansion with a surrounding park near the monastery. In order to integrate the ruins of the monastery into the park, two dams were built in 1806, which have since connected the island to the mainland. The monastery and the associated manor were later sold several times and are still privately owned today (as of 2007).

architecture

Nothing is known about the buildings from early Christian times. Generally speaking, in Ireland during this period it can be assumed that the most obvious building materials have been used. Since oak was widely available in Ireland at the time, it was one of the preferred building materials. The name of the island suggests that there were enough oaks available on site. In contrast to the west coast of Ireland and the Atlantic islands, which are exposed to considerably rougher weather, the rather sheltered location in the Blackwater Valley did not necessarily mean that stones were used as building material.

Only later, but well before the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 12th century, were churches increasingly built as stone buildings. The nave of the monastery, which is 17.07 m long and 7.47 m wide, comes from this period. Typical for this construction period is the preferred use of quite large stones, which were selected and arranged as carefully as possible so that a relatively high accuracy of fit was achieved. However, the special architectural details from the time have been lost. The west window is no longer preserved in its original form, the entire east gable with the old east window was later broken through to connect the nave to the choir, and all the passages were walled up later. Although it can be assumed with certainty that the nave dates from the time before the invasion, an exact dating is very difficult due to the lack of windows and portals in its original state, and this has been avoided in the previous literature for this reason.

All other surviving buildings were not built until the 13th century with some later additions. A dating is possible here due to the adoption of the early English style, which occurred either through relationships between English and Irish monasteries (such as Boyle ) or through the influence of the Anglo-Norman invaders. It was customary in this period for builders and artists to come from England for this purpose. Typical of this style are the very high lancet windows that are pointed at the top. In the choir these windows are 4.57 m high, inside 2.08 m wide and narrow to 0.56 m on the outside. The east window has not been preserved, but based on the remains, Patrick Power assumes that it was 2.08 m wide inside and reached a total height of 6.10 m. The choir area was flooded with light with six southern choir windows, a large east window and four northern choir windows. In comparison, the old nave must have appeared dark.

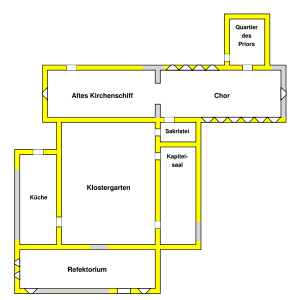

In accordance with the architecture of the Cistercians in Ireland and the few other similarly extensively preserved Augustinian houses in Ireland from the same period as in Athassel and Kells, the other buildings of the monastery were arranged south of the nave. There was no alternative to this on the island, as the nave was already quite close to the northern bank. Immediately to the south of the nave was the inner courtyard, which is 14.86 m wide in east-west orientation and 19.74 m long in north-south direction. In addition to the nave in the north, three further wings are grouped around the inner courtyard, all of which were connected with doors to the inner courtyard.

The east wing was two-story. The sacristy was directly connected to the choir on the ground floor . Further south followed further rooms with the chapter house , the parlatorium and the stairwell that gave access to the dormitory on the upper floor. A three-part window with a height of 1.68 m and an interior width of 1.37 m belonged to the chapter house.

With a length of 21.49 m and a width of 6.17 m, the refectory , which took up the entire southern wing, was particularly generous. Large parts of the southern wall collapsed today. However, a window in the early English style and a window with a round arch, which apparently served as a lectern, remained on the south side. Together with the two windows in the west gable, the room was probably well supplied with light.

The west wing housed the kitchen, which had a door on the north side in addition to the door to the inner courtyard. Here, in an unusual niche, which was formed from the walls of the old nave, the inner courtyard and the west wing and which only remained free to the west, was a brick well, which has now been completely buried. Right next to the door, in close proximity to the fountain, there is a wall opening through which the water drawn from the fountain could flow directly into the kitchen.

Only later was a two-story extension added to the north side of the choir. This probably served as quarters for the prior. On each of the two levels there was only one room, 7.32 m long and 5.59 m wide. In the northwest corner of the extension, a small spiral staircase led to the upper room. The lower room had two doors that led to the choir and outside.

Some structural changes can be traced back to the activities of the Smyth family at the beginning of the 19th century. These include an ogival entrance on the north side of the old nave, a statue in the center of the courtyard depicting the founder Máel Anfaid in the incorrectly historical habit of the Augustinians, a plaque on the east gable of the refectory and a memorial stone in the window of the lectern in the refectory that claims that this is where Raymond FitzGerald was buried. It is entirely plausible that his tomb is in the monastery, but the refectory would be unthinkable for this.

swell

- The martyriology of Oengus , originated in the monastery at Tallaght , whereby the text can be limited in time to the range between 828 and 833. A critical edition is available from Whitley Stokes: The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee . Henry Bradshaw Society 29, London, 1905. (There are three entries relevant to the early history of the monastery. These include the January 31st entry, which takes into account founder Máel Anfaid, the August 14th entry, the reminds of Fachnan Mongach, and the note on August 15 that Fer-dá-chrích mentions as the teacher of Máel-Rúain.)

- The Martyriology of Donegal , compiled by Michael O'Clery in the 17th century. A text edition is available from John O'Donovan and James H. Todd: The Martyrology of Donegal: A Calendar of The Saints of Ireland . Dublin, 1864. A recent reprint was published by Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1432545191 . (There are four entries here: on January 31st for Máel Anfaid, on March 8th for Neman, on August 14th for Fachnan Mongach and on August 15th for Fer-dá-chrích.)

Secondary literature

- Sir James Ware: De Hibernia & antiquitatibus ejus disquisitiones . London 1654. (The entry for this monastery can be found on pages 195–196.)

- Mervyn Archdall: Monasticon Hibernicum ; or, an history of the abbies, priories, and other religious houses in Ireland. London, 1786. (On pages 695 and 696 there is an entry for this monastery.)

- Patrick Power: Ancient Ruined Churches of Co. Waterford . From: Journal of the Waterford and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society , Volume 4, Volume 1898, Pages 83-95 and 195-219. (See the section on Molana Monastery on pages 209–212.)

- WH Grattan Flood: Molana Abbey, Co. Waterford . From: Journal of the Cork Historical and Archæological Society , Volume 22, year 1916, Issue 109, pages 1–7 with two unnumbered pages. (This article examines in great detail all historical evidence of the monastery from the later Middle Ages and from the period after the Reformation. The article is supplemented by four photographs.)

- Patrick Power: The Abbey of Molana, Co. Waterford . From: The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland , Volume 62, Year 1932, pages 142–152. (This article analyzes in detail the architecture of the monastery.)

- Harold G. Leask: Irish Churches and Monastic Buildings . Second volume, Dundalgan Press, 1960. (There is a brief section on this monastery on page 146 under the heading Ballynatray .)

- Aubrey Gwynn and R. Neville Hadcock: Medieval Religious Houses Ireland . 1970, Longman, London, ISBN 0582-11229-X . (The entry for this monastery can be found on page 187.)

- Peter O'Dwyer: Célí Dé: Spiritual reform in Ireland 750-900 , Editions Tailliura, Dublin 1981, ISBN 0-906553-01-6 . (This work deals in detail with the special role that Molana Monastery played in this reform movement.)

Web links

References and comments

- ↑ See for example the entry Dair on page 67 in the work by Deirdre Flanagan et al .: Irish Place Names . Gill & MacMillan, 1994, ISBN 0-7171-2066-X .

- ↑ See the August 14 gloss in The Martyriology of Oengus, page 184, below in the Whitley Stokes edition.

- ^ The corresponding entry from the Black Book of Limerick was documented by TJ Westropp: Island Molana Abbey, County Waterford . From: The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland , Volume 33, Year 1903, Page 425 in the Miscellanea section .

- ↑ On map sheet 81 from the Discovery Series of the Ordnance Survey of Ireland, ISBN 1-901496-56-2 , the monastery Molana Abbey is mentioned (map grid position X 080 828). Leask puts the term Abbey in quotation marks on page 146 and immediately indicates the rank of a priory.

- ↑ This emerges from a stone tablet that was attached to the monastery itself by the former owners: This Abbey anciently called Darinis or The Island of Saint Molanfide since Molana was united to the Mainland of Ballynatry by Grice Smyth Esq AD 1806. It was an Abbey of Canons Regular, founded in the 6th Century by Saint Molanfide who was the first Abbot. In Geraldine Carville's work on page 71, the year 1850 is mentioned differently: The Occupation of Celtic Sites in Ireland by the Canons Regular of St Augustine and the Cistercians . Cistercian Publications, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 1982, ISBN 0-87907-856-1 .

- ↑ See page 128 in the work of EG Bowen: Saints, Seaways and Settlements in the Celtic Lands , University of Wales Press, 1977, ISBN 0-7083-0650-0

- ↑ See the essay by Léon Fleuriot : Brittany and the Bretons in the relations between the Celtic countries and continental Europe from the 4th to the 10th century . From the volume Virgil von Salzburg , edited by Heinz Dopsch and R. Juffinger , pages 52-58, Salzburg, 1985.

- ↑ See the 6th chapter from the work of Meike Blackwell: Ships in Early Irish History . Ballinakella Press, 1992, ISBN 0-946538-21-2

- ↑ See Sir James Ware, pp. 195-196. The statue of Máel Anfaid erected in 1820 mentions the year 501: This statue is erected to the memory of Saint Molanfide who founded this Abbey for Canons regular AD 501. He was the first Abbot and is represented here as habited according to the Order of Saint Augustine. This Cenotaph and Statue are erected by Mrs. Mary Broderick Smyth AD 1820 . However, no further evidence is known for this. Gwynn, for example, only adopts the information provided by Sir James Ware.

- ↑ See page 55 in Whitley Stokes: Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee

- ↑ A small legend of saints about him can be found on page 56 in Whitley Stokes: Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee . It is also included on page 296 of the A Celtic Miscellany collection . Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-044247-2 .

- ↑ This hypothesis is discussed by Peter O'Dwyer on page 37. The corresponding entries in the annals are U609.1 in the annals of Ulster and M605.3 in the annals of the four masters . The dating has been corrected according to the tables by Daniel P. Mc Carthy: The Chronology of the Irish Annals , 1998, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 98C, pages 203-255, further information and link to the text

- ↑ If the aforementioned hypothesis is correct, then this dating cannot be maintained. There is no annalistic evidence for him. The dating was taken over by Aubrey Gwynn with the addition apparently . He quotes as sources the Acta Sanctorum Hiberniae and Walter Harris, published in 1645 by John Colgan : The works of Sir James Ware concerning Ireland revised and improved . First volume, Dublin 1739. Walter Harris even assumes the first half of the 6th century: St. Fachnan, a Man of wisdom and probity (as the Writer of the Life of St. Mocoemog calls him) flourished in the beginning of the sixth century. This can also be found in the corresponding entry for August 14th in the Acta Sanctorum of the Bollandists for DE S. Fagnano episc. et conf. in Hibernia : Waræus, quem antea citavi, pag. 220 de episcopis Rossensibus agens, S. Fagnanum eisdem accenset primo loco, variasque insuper de illo suggerit notitias: “Sanctus Fagnanus, vir sapiens & probus” (ut eum vocat scriptor Vitus S. Mochoëmogi ) claruit seculo sexto ineunte. The work De praesulibus Hiberniae, commentarius A prima gentis hibernicae ad fidem Christianam conversione, ad nostra usque tempora by Sir James Ware, which appeared in Dublin in 1665, is quoted. Peter O'Dwyer does not go into Fachnan Mongach in his discussion on the limitation of the lifetime of Máel Anfaid.

- ^ See 583 at Walter Harris: The works of Sir James Ware concerning Ireland revised and improved . First volume, Dublin 1739. A partial reference to this can also be found in the manuscripts Rawlinson B. 505 and Laud 610 in the Bodleian Library . See page 185 of Whitley Stokes: Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee .

- ↑ See page 133 in Kathleen Hughes : The Church in Early Irish Society . Methuen & Co Ltd, 1966.

- ↑ See James F. Kenney : The sources for the early history of Ireland: Ecclesiastical , ISBN 1-85182-115-5 , page 468 and following. The most detailed account of this reform movement so far can be found in the work of Peter O'Dwyer. The care given to the poor and sick is documented by Colmán Etchingham: Church Organization in Ireland AD 650 to 1000 , ISBN 0-9537598-0-6 , page 359.

- ↑ See the Annals of Ulster , entry U747.12. The dating has been corrected according to the tables by Daniel P. Mc Carthy: The Chronology of the Irish Annals , 1998, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 98C, pages 203-255, further information and link to the text

- ^ See Kenney, pages 468 and 469. Kenney probably based his guess on the entry on Fer-dá-chrích on August 15: Aedh was his name in reality, Grandson of Aithmet, good was his deed, True brother, after victory with fame, To Maelruain, our teacher. Aedh is the actual name of Fer-dá-chrích. The latter only means “man of the two districts”, which indicates his dual function as abbot and bishop. A corresponding entry can be found in the Martyrologium of the Oengus on August 15. Peter O'Dwyer firmly assumes on page 30 in his work: His teacher was Ferdácrích who seems to have been a relation of his.

- ↑ See pages 59 and 193 at Peter O'Dwyer.

- ↑ For the connection between hibernensis and the reform movement, see pages 15 and 193 in Peter O'Dwyer's work Célí Dé , ISBN 0-906553-01-6 .

- ↑ See the Annals of Ulster , entry U725.4. The dating has been corrected according to the tables by Daniel P. Mc Carthy: The Chronology of the Irish Annals , 1998, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, Volume 98C, pages 203-255, further information and link to the text

- ↑ See introduction by Hermann Wasserschleben : The Irish cannon collection. Bernhard Tauchnitz, Leipzig, 2nd edition, 1885.

- ↑ See page 143 in Patrick Power's 1932 essay. It should be noted that entry M819.4 in the annals of the four masters relates to Dairinis in Wexford, as Patrick Power also explains. This is also an implicit answer to the corresponding statement in the article by Flood, which assumed a documented hold-up.

- ↑ See the entry on Lismore on page 91 by Aubrey Gwynn. The corresponding entries in the annals of Inisfallen are AI833 and AI883.1.

- ↑ See page 5 in Alicia St. Leger: Youghal Historic Walled Port: The Story of Youghal . ISBN 0-9523401-0-0

- ↑ See entry M945.7 in the Annals of the Four Masters . There Glendine is given as the place of the conflict.

- ^ See Gwynn and Hadcock, 146.

- ↑ See Patrick Power's 1932 essay, 143.

- ^ A b See Aubrey Gwynn, 187.

- ^ See the 1932 essay by Patrick Power, p. 144.

- ↑ See Ware, page 196.

- ↑ See the entry in Aubrey Gwynn.

- ↑ See page 3 for the article by Flood. Flood believed the canons could stay until 1560.

- ↑ The date was taken from the article by Flood, page 3. The list can be found at both Flood and Power.

- ↑ The life data have been added to this bibliography ( memento of the original dated November 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ). Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. taken.

- ↑ See the 1932 essay by Patrick Power, pp. 145 and 146.

- ↑ See page 4 in the article by Flood. Flood here refers to page 43 of Hayman's book: Memorials of Youghal , 1863, which in turn refers to a book by the Jesuit John Coppinger: The Theater of Catholique and Protestant Religion. from the year 1620. (The latter year was taken from books.google.com.)

- ↑ See Flood, 3; Gwynn, 187; and Patrick Power's 1932 essay, 147.

- ↑ a b c See page 4 in the article by Flood.

-

↑ The article of March 21, 2003 of the Irish Examiner reports on the sales intentions of the then owners Serge and Henriette Boussevain: War set to hit sale plans for mansion ( Memento of February 1, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

Another article of March 25, 2004 reports on the sale: Archivlink ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) - ↑ The dimensions were taken from the article by Patrick Power from 1932.

- ↑ See Harold G. Leask: Irish Churches and Monastic Buildings . Volume 1, Dundalgan Press, 1955, pages 51-53.

- ↑ This dating was done by Patrick Power in his 1932 paper.

- ↑ See page 5 in Colum Hourihane: Gothic Art in Ireland 1169-1550 . Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09435-3 .

- ↑ See the article from 1932 by Patrick Power, pages 150 and 151.

- ^ At the time, see The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee at CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts

- ↑ The Waterford County Library has digitized volumes 1-18 of this journal, here online ( Memento of December 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

Coordinates: 51 ° 59 ′ 50 ″ N , 7 ° 53 ′ 0 ″ W.