Congress Poland

|

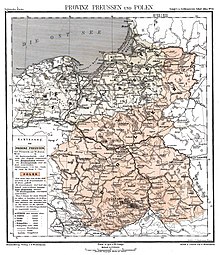

Congress Poland Kingdom of Poland Królestwo Polskie ( pl ) Царство Польское ( ru ) (Weichselland) 1815–1916 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Constitution |

Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland 1815–1832 Organic Statute 1832–1863 / 67 |

||||

| Official language | Polish , Russian | ||||

| Capital | Warsaw | ||||

| Form of government | kingdom | ||||

| Government system |

Constitutional Monarchy Protectorate of Russia 1815–1867 Russian Province 1867–1916 |

||||

| Head of state |

Emperor of Russia 1815–1830 1831–1916 (unofficial) |

||||

| Head of government |

Russian governor Viceroy 1815–1867 Governor General of Warsaw 1867–1916 |

||||

| surface | 127,000 km² | ||||

| currency |

Zloty (until 1850) Russian ruble (from 1850) |

||||

| founding | June 9, 1815 ( Congress of Vienna ) | ||||

| resolution | 1867 Incorporation into the Russian Empire November 5, 1916 (officially) Creation of the reign of Poland |

||||

| National anthem |

Mazurek Dąbrowskiego 1815–1867 Bosche, Zarja chrani! 1867-1916 |

||||

| Time zone | CET | ||||

|

|||||

Congress Poland refers to the constitutional kingdom of Poland , which was created in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna (hence the name) as the successor to the Duchy of Warsaw founded by Napoleon in 1807 . It was closely linked to the Russian Tsarist Empire through personal union and, after losing its remaining rights, was also referred to as Weichselland from the late 1860s .

history

prehistory

After Poland-Lithuania had been severely weakened in the second half of the 18th century by numerous previous wars and internal conflicts, Poland was gradually partitioned among the neighboring powers of Russia , Prussia and Austria in 1772, 1793 and 1795 , so that no independent one for over 120 years Polish nation-state existed longer. The area around Warsaw became part of the newly created South Prussia . Napoleon Bonaparte established the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807 on the territories annexed by Prussia in 1793 and 1795 and expanded it in 1809 to include Austria's division from 1795. The Duchy was a rump and satellite state of Poland with King Friedrich August I of Saxony on the throne.

Congress Poland

After Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna restored the Polish monarchy in 1815 . Tsar Alexander I , influenced by his friendship with Adam Jerzy Czartoryski , revived the Polish state and became King of Poland in personal union.

In theory it was an autonomous state. Congress Poland, however, remained under Russian control. Alexander's brother Constantine , as military governor of Warsaw and general of the Polish troops, if not formally, then in fact had the strong power of a viceroy. In 1820 he married a Polish countess. However, Constantine's rudeness, tyranny, and military drill were not particularly helpful in winning Poland over to him and Russian rule.

The Kingdom of Poland , as its official name, emerged from the former Duchy of Warsaw without the Grand Duchy of Posen and the areas of Lubawa , Toruń and Chełmno (ceded to Prussia) and without the Free City of Krakow (first independent, then to Austria). Apart from the head of state, the new state should have strong autonomy and the old constitution of 1791 according to treaties of 1815 . The laws should be enacted by the Sejm , an independent army, currency, an independent state budget and a penal code etc. should be maintained and should be separated from the actual tsarist empire by a customs border (administration distincte) .

In fact, the tsar concentrated the great power in his hands and ruled moderately autocratically with the help of the Russian viceroy, who also held the command of the army, and the imperial commissioner Nikolai Nikolayevich Novossilzew and his secret services. The resolutions of the Congress of Vienna were constantly disregarded. In 1819 the freedom of the press was abolished and censorship introduced, Freemasonry was banned in 1821, parliament ceased to meet publicly from 1825, and a board of directors was in control. The political situation was marked by oppression by the Tsar and his Warsaw governor Novossilzew as well as by the arbitrariness of Constantine. Nevertheless, Congress Poland was the most liberal part of the Russian Empire with its own parliament, administrative and school system. In contrast to the rest of Russia, the Catholic Church was respected and received endowments and certain privileges . As a further concession, the officials were also Polish and spoke Polish.

Many Poles, especially the youth shaped by the spirit of Polish romanticism , were nevertheless very dissatisfied with the Russian dominance. The news of revolutions in Paris and Belgium had a group of young conspirators, especially cadets of the Warsaw cadet school, take up arms: On November 28, 1830 in Warsaw broke November Uprising of Czar Nicholas I was deposed by Parliament as king, his brother Constantine was attacked in his castle, but was able to escape disguised as a woman. After about ten months, Nicholas restored his power with the help of Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich's troops . In 1831 he made the Marshal Prince of Warsaw and in 1832 replaced the previous constitution with the constitutional law, the Organic Statute . The Polish army, the Sejm and local self-government were also dissolved. The resolutions of the Congress were thus invalid and the remaining autonomy of Congress Poland was abolished. What remained was, among other things, the title of Namiestnik ( Viceroy ) for the governor Paskewitsch, who began to Russify the country. 286 emigrants were sentenced to death, their property confiscated and distributed to Russian generals. The University of Warsaw opened in 1816 and most of the teaching institutes closed. All clubs were banned. Private gatherings were allowed when the surveillance officer was received. Russian became a compulsory language for all civil servants, and there was strict censorship of books and music. Tsar Nicholas in a speech in Warsaw in 1835: “ If you insist on holding on to your dreams of a special nationality and an independent Poland and all these chimeras, you will cause great disaster on yourself. I have had a citadel built and [...] at the slightest disturbance I will have the city bombarded. "

Only the Russian defeat in the Crimean War in 1855 and the assumption of office of the new Tsar Alexander II led to Polish-Russian cooperation again: under the leadership of the moderate Aleksander Wielopolski , a civil government consisting only of Polish politicians was appointed in 1862. The unification efforts of Italy, however, inspired the democratic camp to take up an armed struggle in January 1863 ( January uprising ). Military disproportionate relations with the Russian troops and unsuccessful attempts to mobilize large masses of peasants, as well as disagreement among political emigration and a lack of support from European states, caused the uprising to fail. The drastic Russian reprisals, expropriations and deportations to Siberia ultimately weakened the nobility within Polish society.

Transition to the Weichselland

In 1867 the office of viceroy and the coat of arms of Congress Poland were abolished. The area, now divided into ten governorates , was integrated directly into the tsarist empire. The previous name was never officially changed, but since the 1880s the name Weichselland ( Russian Привислинский Край , Priwislinskij Kraj ; Polish Kraj Nadwiślański ) appeared more and more frequently in various administrative acts , and the word "Poland" was even used as a geographical term for avoided on the Russian side.

Kings of Congress Poland

- 1815–1825 Alexander I.

- 1825–1830 Nikolaus I († 1855) - deposed as king in 1830, in power again since 1831 without being reinstated as king

Viceroys

- unofficial: Grand Duke Konstantin Pawlowitsch Romanow (1815–1830)

- Józef Zajączek (1815–1826)

- 1826–1831 vacant, represented by a board of directors

- Ivan Fyodorowitsch Paskewitsch (1831–1855)

- Mikhail Dmitrievich Gorchakov (1855 - May 3, 1861)

- Nikolai Sukhozanet (May 16, 1861 - August 1, 1861)

- Karl Lambert (Karl Karlovich Count Lambert, 1861)

- Nikolai Sukhozanet (October 11, 1861 - October 22, 1861)

- Alexander von Lüders (November 1861 - June 1862)

- Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolajewitsch Romanow (June 1862 - October 31, 1863)

- Friedrich Wilhelm Rembert von Berg (1863–1874)

The title of Viceroy is replaced by Governor General of Warsaw .

See also

literature

- Manfred Alexander : Small history of Poland. Reclam, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-010522-6 (source).

- Roman Dmowski : Germany, Russia and the Polish question (excerpts). In: Andrzej Chwalba (Ed.): Poland and the East. Texts about a tense relationship (= thinking and knowing. A Polish library. Vol. 7). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-518-41731-2 .

- Jürgen Hensel (Ed.): Poles, Germans and Jews in Lodz 1820–1939. A difficult neighborhood (= individual publications by the German Historical Institute Warsaw. Vol. 1). fiber Verlag, Osnabrück 1999, ISBN 3-929759-41-1 .

- Harold Nicolson : The Congress of Vienna. A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. Grove Press, New York NY 2001, ISBN 0-802-13744-X .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Norman Davies : God's Playground. Volume 2: 1795 to the present. Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-925340-4 , p. 225 ( preview in Google Book Search)

- ^ Królestwo Polskie . Encyclopedia PWN. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ↑ Alexander Nikolajewitsch Makarow (1888–1973): The Russian-Polish legal relations since 1815 with special consideration of citizenship issues. In: ZaöRV . 1929, p. 330 ff. (PDF; 3.6 MB); Wojciech Witkowski: Themis polska. The first Polish legal journal (1828–1830). In: Michael Stolleis , Thomas Simon (ed.): Legal magazines in Europe. P. 114 ( bibliographic information ).

- ↑ Charles Seignobos: Political History of Modern Europe. Leipzig 1910, p. 532 ff.

- ↑ Juliusza Bardacha, Moniki Senkowskiej-Gluck (Red.): Historia pánstwa i prawa Polski. Volume 3: Wojciech M. Bartel: Od rozbiorów do uwłaszczenia. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa 1981, ISBN 83-01-02658-8 , p. 67.

- ^ Marek Czapliński: Słownik encyklopedyczny. Historia. 5th edition. Wydawnictwo Europa, Wrocław 2007, ISBN 978-83-7407-155-0 , p. 199.