Cultural history of the potato (Luxembourg)

According to a popular representation, the first potatoes are said to have been made around 1720 under Emperor Charles VI. found their way to Luxembourg , which at that time was part of the Austrian Netherlands as the Duchy of Luxembourg . However, their spread failed because of the backwardness of the farmers. It was not until the “good” Empress Maria Theresa , who around 1746 had potato tubers distributed free of charge to her subjects, that the breakthrough came, not least because the population received precise instructions on how to grow potatoes. In the villages, the parish messenger was in charge of explaining to the people after Sunday mass how and when to plant potatoes. The Maria Theresa version is already called into question by the historically documented fact that the Baron von Erpeldingen distributed potatoes to his farmers in 1740, but crucially above all by a study published in 1852 on the introduction of the potato into the duchy Luxembourg.

A study from 1852

Its author was the former governor of Luxembourg Gaspard Théodore Ignace de la Fontaine and its title was Notice sur les pommes de terre et sur l'époque de leur introduction dans le pays de Luxembourg et les Ardennes wallonnes .

The role of Maria Theresa elegantly relegated de la Fontaine to the realm of legends. The potato was already cultivated in many places in the Duchy in 1746, and at that time even in the Ardennes it was no longer just in the gardens, as was initially the case everywhere, but also in the fields. The analysis of some of the trials surrounding the tenth of the potato led him to estimate that the introduction of the potato took place around 1720.

Trials of the potato tithing

The processes mentioned were about the following: The farmers were subject to the tithe (French: la dîme ), and accordingly had to give up the tenth part of their production, every tenth sheaf of grain, for example, to the tithe. These tithe levies had been securitized and unchallenged for centuries. Difficulties arose when more and more previously unknown plants appeared at the beginning of the 16th century as a result of voyages of discovery. Emperor Charles V provided two ordinances, one from 1520 and the other from 1530, to make things clear: the new plants are subject to a tenancy fee; the tithe may only not be charged if it can be shown that it has not been demanded by the new plant for forty years. In these trials, the farmers were concerned with proving by testimony from very old witnesses that no tithe had been levied on potatoes for more than forty years, and that any claims of the tithe lord were barred.

Knaphoscheid 1709

Even if these testimonies should be taken with a little caution, they still provide valuable information about the approximate time of the first cultivation of the potato in the respective localities. Most interesting in this regard is the tithing trial of the Jesuit subjects von Boegen and Wintger , where a 77-year-old witness testifies on February 7, 1764 that in the cold winter of 1709 in Knaphoscheid they started to plant potatoes in the garden and then in the fields , and in 1718 he saw half an acre planted in the field at Boegen.

The reference to 1709 makes you sit up and take notice, because from a meteorological point of view that was an extraordinary year! The rainy summer of 1708 had led to a bad harvest, which was followed by the longest and coldest winter (1708/09) that had been experienced in living memory. The thermometer sank to the equivalent of 30 degrees below zero, the wine froze in the barrels in the wine cellar, the fruit trees were bursting with the cold, birds, the chronicle says, fell dead to the ground in flight. The sown hard fruit ( winter grain) froze to death. Because of the persistent frost, the spring sowing ( summer grain) could not take place at the right time, so that there was ultimately neither grain nor straw. The famine was inevitable and so great that starving people ate dead animals. - Actually, exactly the right moment to try planting the potato, which you might have suspected up to now, but then please in spring, and not in winter, as the above witness said. In any case, the famine of 1709 and the following years may have decisively promoted the naturalization and spread of the potato in the Duchy of Luxembourg. It cannot be ruled out that the local collateral damage caused by the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) may have contributed to this development.

Esch / Sauer 1707

In a trial against the inhabitants of the village of Wéris before the court of Durbuy (now Belgium) in 1755 , three witnesses testified that potatoes had been planted after the harsh winter of 1709; other witnesses mentioned the years 1703, 1706 and 1710 and 1712. The following statement by the historian Alphonse Sprunck fits into this scheme : "Potatoes were grown in small quantities in the Duchy of Luxembourg as early as 1710, probably first in the small slopes that were on hilly terrain between individual fields." The Luxembourg postperceptor and writer Gregor Spedener believed he knew more precisely and therefore wrote that the first potato farmer in the country was Charles Bernard du Bost-Moulin from Esch ad Sauer , who in 1707 brought tubers "from distant lands" and then planted them in Esch / Sauer.

It is noteworthy that the two alleged first plantings of the potato on what is now Luxembourg's soil - Knaphoscheid and Esch / Sauer - are in the Ösling. This corresponds to the general historical knowledge that the potato was first grown in the low-yielding low mountain ranges, the "land of the poor people". It is also remarkable that the Ösling lies exactly in the thrust of the potato advancing from the Rhineland from the east.

The Jerusalem artichoke

In the Luxembourg court records of the 18th century, the potato appears under the French name topinambour or the German name Grundbirne .

The name topinambour (dt .: Jerusalem artichoke ) was originally used for a tuber plant imported from North America around 1600 , which at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries in Alsace and Lorraine under the name pomme de terre (literally translated: Potato ) was planted. Its scientific name is Helianthus tuberosus ; it is a relative of the sunflower, which also comes from North America . In Wallonia it was called canada because of its origin , an abbreviation for truffe du Canada (Canada truffle; because of the truffle-like tuber) or artichaut du Canada (Canada artichoke; because of the artichoke-like taste of the cooked tuber).

It used to be said that the potato was already present in Alsace in 1623, but today we know that this was Jerusalem artichoke, just as it was in the Palatinate , where the latter was grown in the open field around 1660.

The Jerusalem artichoke came to Luxembourg at the beginning of the 18th century. In the Flore du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (1875) by the pharmacist Jean Henri Guillaume Krombach and in the Flora der Heimat (1897) by Edmond J. Klein , this plant is referred to as Russian Gromper , Russian potato. This and similar names are also known elsewhere in the German-speaking area: Russian drakes (Erpel = potatoes) (in places on the Lower Rhine) and Russian ground pear (in Bavarian Swabia ). Here “Russian” does not seem to be primarily used in its geographical meaning, but rather in the sense of inferior, as was done in Baden by adding “Ross”: Rosserdepfel, Rossherdäpfel, Rossepfel, Rosskartoffle, Rossgrumbiire , or in Lower Austria with the name Judenerdapfel .

When the potato later joined the Jerusalem artichoke and began to displace it, the names of the two neophytes were increasingly confused, especially at the administrative level, while the people consistently between topinambour (Helianthus) and poire de terre , ground pear , crompire (potato) knew how to distinguish, at least at the beginning. As is well known, the potato later became a Erdapfel , aardappel or pomme de terre . This explains why a lawyer from Brussels was able to assert during a trial before the High Court of Durbuy (Duchy of Luxembourg) in 1764 that it was generally known that patates (original name for sweet potatoes ), topinambours , crompires , canadas , pommes de terre and poires de terre are synonymous.

Temporary coexistence of Jerusalem artichoke and ground pear

The fundamental work La pomme de terre en Wallonie au XVIIIe siècle (1976) by the Belgian historian Fernand Pirotte allows the following overall presentation of the distribution of the potato in Luxembourg:

- 1. At the beginning of the 18th century, the first previously unknown tuber plant, the Jerusalem artichoke, was introduced into the Duchy of Luxembourg, probably from Lorraine, under the name pomme de terre (literally: potato), which is common in Lorraine .

- 2. Around 1715–1720 another tuber plant, the potato, the poire de terre or (literally) ground pear , called crompire or grompir by the people , was imported from the Rhineland (later Rhine province ) . (Potato deposits before this period, such as in Esch / Sauer, Knaphoscheid, etc., should therefore be regarded as a kind of harbinger, provided that they correspond to a historical fact.)

- 3. The two species coexist for some time, with the potato dominating rapidly, which has surpassed the Jerusalem artichoke within 20 to 25 years, i.e. before 1740. In the 1750s, at the latest by the beginning of the 1760s, the potato definitely supplanted the Jerusalem artichoke.

Paradoxically, the authorities kept the name topinambour , but used it from around 1740/50 on for the potato, which they had practically ignored until then, as their cultivation was restricted to the gardens and thus remained tithing-free.

In the meantime, the potato had also found its place in the three-field economy practiced at the time . Instead of leaving a field fallow every three years and using it as pasture for cattle, the farmer now planted the new fruit, which loosened the soil so nicely that it could be sown with grain as soon as it was harvested.

The potato also became attractive to thieves. For example, on November 13, 1752 , the city court of Echternach sentenced two boys who had stolen potatoes in a garden at vesper time to “stand in the lumprinck or neck iron for half an hour” while their two followers next to them “just walked with the ground for that long around the neck and discovered head ”had to stand. The cultivation of potatoes must have been fairly widespread in the Echternach area at that time. This is confirmed by a report from 1764, in which it is said that the farmers of the canton would plant the "poires de terre" or "topinambours" in large quantities.

Luxembourg potatoes for Lower Austria

While potato cultivation was already widespread in the middle of the 18th century in Luxembourg, which at that time was part of the Austrian Netherlands, which was part of Austria, this hardly seems to have been the case in Austria itself. The Luxembourg clergyman Johann Eberhard Jungblut (1722–1795) is said to have played a decisive role in its spread in Lower Austria . In 1761, shortly after taking office as pastor in Prinzendorf an der Zaya , he is said to have imported potatoes there from his so-called “Dutch” , or more correctly expressed, from his Austrian-Dutch homeland. From Prinzendorf, the potato is said to have spread to the Weinviertel and beyond. Jungblut went down in history as the “potato pastor” of Prinzendorf.

Potatoes for Napoleon

From 1795 to 1815, Luxembourg belonged to France as the Département des Forêts (Forests Department) . “During the French era,” said a Luxembourg magazine years ago, “the cultivation of potatoes was strongly promoted. The revolutionary rulers did not always have the people's food in mind. The more potatoes were grown, the more grain could be confiscated for Napoleon's troops. For this reason the sub-prefects had to give precise details about the potato cultivation. Their reports show that at that time a number of different varieties were already growing in the fields of the forest department, such as 'Ardennes', 'Française' or 'Petite souris'. "

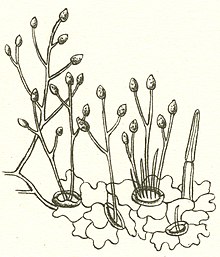

Even after Napoleon's defeat, efforts were made in Luxembourg, which had now been elevated to the status of a Grand Duchy, to encourage the cultivation of potatoes. In the administrative memorial, the official gazette of the Grand Duchy, the population was informed about the potato, its cultivation, propagation and use. The following topics were addressed in the memorial of 1817: Optimization of the yield of the individual plants by means of subsidence, propagation by planting the torn off shoots of the sprouting potato; Precautions for harvesting and advice on how to store the potatoes, including the drying of fresh and frozen potatoes and how to make flour or potato starch from them. The "method of processing the potatoes into an excellent flour" was discussed in more detail in 1818, and that one can make brandy from potatoes or that they can be propagated by sowing their seeds.

Weeding out the potatoes was more advantageous than heaping them up, the memorial of 1819 said. Then there was talk of storing the potatoes again in barrels (1824) or in boxes with ashes as intermediate material (1829). Breaking off the flowers, which prevents fruit and seed formation, can increase the yield by a seventh, it was said in 1830, and if you can't hand your frozen potatoes to a brandy distillery, they should be air-dried and in the Grind the mill to flour. One should not dry the frozen potatoes in a place where rats and mice have free access, "because they are very greedy for the flour-light (sic) substance of the potatoes".

Potato brandy

The fact that brandy can be made from potatoes seems to have been recognized by the middle of the 18th century at the latest. Around 1787 potato schnapps was distilled in Kurtrier. The potato schnapps distillery only experienced its breakthrough after the invention of the Pistorius distillery (1817). The growing potato cultivation and the now cheaper production method led to a real boom in schnapps.

In his bitter struggle against alcohol abuse, the Luxembourg clergyman Joseph Kalbersch (1795–1858), pastor in Erpeldingen, tried potato schnapps in particular in 1854: “Whoever was seduced first to draw brandy from ground pears knows I don't, don't ask to know at all, completely forgotten, he remains unhappy enough. Only he could not easily foresee the millions of tribulations that his invention would cause. ”By burning the potato is transformed into a poison that is drunk by poor people: poor farmers, seduced craftsmen, day laborers, servants, here and there too a rich farmer but on the way to poverty. And so the people had to go hungry because their food was stolen: “Before we burned the potatoes for brandy, and before our people have drunk themselves into poverty in this starvation poison, every household, especially in the country, had more abundance than lack of pears . Anyone who thinks back twenty years in the past knows that. But since our poorer classes have been drinking more than seven thousand ohms of potato pest every year , they have made it impossible for them to acquire land and seed potatoes. "

In 1854 the distilling of brandy from potatoes was forbidden, but not because of the moral considerations cited by Kalbersch, but because the poor harvests of 1852 (potatoes) and 1853 (grain) led to a great shortage of food, which in 1853 / 54 degenerated into a downright famine, and became even more dramatic with the cholera epidemic of 1854. This ban was only lifted three years later.

blight

A ban on making schnapps from potatoes or grain had already been in place in May 1846, as a result of a previously unknown potato disease, potato rot , which first appeared in Luxembourg in the summer of 1845.

It is caused by a fungus that is known today under the scientific name Phytophthora infestans . Its area of origin was in central Mexico . The parasite had come to Flanders in the winter of 1843/44 from North America, where it first appeared in 1843, with infected potatoes . Here it went unnoticed for the first year, only to hit even more devastatingly afterwards.

Most of the European potato harvest in 1845 fell victim to the disease. In Luxembourg, the poor harvest of 1845 had led to a food shortage that would last until 1847, fueled by the poor grain harvest of 1846 and ruthless speculative deals. Neither the initial monitoring and the subsequent ban on the export of potatoes nor the aforementioned ban on distilling schnapps could change anything.

Joseph Kalbersch understood the potato rot as a divine intervention against the abuse of the potato for the production of schnapps: “In [1845] (Kalbersch writes: 1846) the Lord God himself took over to moderate the burning of the ground pears. A searing thought of the Eternal, a dies irae, had passed over the potato fields. In the middle of summer their banners were withered and the tubers were rotting in their careful mother's lap [sic]. ”And yet the gentleman could only boast a partial success, for the distillers were not deterred, and for want of better goods they processed then the rotten tubers. "So this stinking rubbish was thrown into the stilling flask," said Kalbersch indignantly, "and a poison was driven out of it, with which one could have killed all the horses and oxen in the country."

The potato rot, just like other catastrophes, represented a clear punishment from God for Nicolas Nilles , at that time pastor in Tüntingen and later professor at the University of Innsbruck . In his book Cholera, Potato Disease, Drought, Flood, Hailstorm, Earthquake and War, taxation and need was accordingly: “For Christians (...) the failure of food in the field and the taxation and need caused by it (...) is the execution of God's just judgment; but at the same time a kind, a mild, and merciful chastisement. This plague is, in other words, righteousness and severity coupled with goodness and mercy. "

Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado beetle , which like the potato blight pathogen, had come across the Atlantic from America to Europe, was first discovered in Luxembourg on June 23, 1936 in Steinsel ( Müllendorf ), and larvae of the beetle were found in Mamer at the same time . In July 1936 a new stove was discovered in Mamer, and there were other deposits in Limpertsberg and Neuhäuschen . According to a newspaper note, a Colorado beetle was also found in Differdange on Saturday, July 11, 1936, by a pupil at the school, a rather atypical location. An "official" confirmation of this find does not seem to have been given, so that the question remains whether it was really the Colorado beetle or whether there was a mistake, as was the case with the ladybug in Bissen at the end of June 1936 or it was the case in Wiltz with the lily beetle . From now on the Colorado beetle was definitely naturalized in Luxembourg and was able to spread throughout the country in the following years.

Linguistic

The potato is now called Gromper in Luxembourg . Mid-19th century, the potato was transition Jewelers Lexicon of the Luxembourg vernacular but still (1847) Grompir called, a term which, under the form "Krombièr" in the Luxembourg Flora Krombach (1875) to the last quarter of the 19th Century survived. In the Dixionèr fun de Planzen (dictionary of plants), which the dentist Joseph Weber published in 1890, only the name Gromper appears, just like in the flora of Edmond J. Klein's homeland from 1897. We find it in the Rhine Franconian language term Grumbir and the Palatine, the terms Grumbeere or Grombeere , clear transitional forms from the high German base bulb to Luxembourg Grompir or Gromper !

Other Luxembourgish names for the potato are Badatten or Padatten (from the French patates , originally sweet potatoes) and, for fun, Buppen or Bippercher . In Bondorf there Mierben and Meerben .

The “eyes” of the potato were called Batz in Luxembourgish , one of the meanings of the word that was still used in the 1930s, whereas today Batz only means the casing of the apple. When the buds of the eyes germinate, they become kéngen , i.e. H. Potato shoots.

From the grub of the cockchafer , originally Kiewerleksmued (beetle grub) or wäisse tired (white grub) called the potato was after naturalization in time a Gromperemued (potato Made).

After his immigration, the Colorado beetle became the Grompere beetle in Luxembourgish ; other neologisms such as Gromperebock or Gromperekiewerlek have hardly established themselves.

The potato in the legend

One of the many legends that Nicolas Gredt published in his saga treasure trove of Luxembourg in 1883 is about a miller's farmhand from Reckingen , an old witch and bewitched potatoes .

literature

- H. Blackes (pseudonym: Heinr. Olim Hirth von Weidenthal): The trial of the potato tithing in the forest valley from 1742. In: 50e anniversaire FC Kopstal. Luxembourg 1983, pp. 134-142.

- E. Fischer: Notices historiques on the situation agricole du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg . 2e éd. Luxembourg 1860, 254 pp.

- J. Flammang: The priest of potatoes from Prinzendorf: a Luxembourg priest introduced the potato to Lower Austria. In: Letzeburger Bauere-Kalenner, Jg. 38 (1986): 185-193; Vol. 39 (1987): 238-239.

- GTI de la Fontaine: Notice sur les pommes de terre et sur l'époque de leur introduction dans le pays de Luxembourg et les Ardennes wallonnes. Publications de la Société archéologique du G.-D. de Luxembourg, VII, Luxembourg 1852, pp. 189-196.

- I. Haslinger: May it rain potatoes. A cultural history of the potato with 170 recipes. Vienna 2007, 179 pp.

- J. Hess: Old Luxembourg Memories. Contributions to Luxembourg culture and folklore. Luxembourg 1960, 389 pp.

- N. Jakob: From Inca vegetables to Eislécker stew. In: Revue, Vol. 36 (1981), No. 20, Luxemburg 1981, pp. 26-31.

- J. Kalbersch: Use and abuse of spirits, or wine and brandy in the Middle Ages and in our time. Part 2: The brandy. Diekirch 1854, 491 pp.

- EJ Klein: From a biological point of view, the flora of our homeland as well as the main foreign plant species cultivated here. Diekirch 1897, XII, 552 pp.

- W. Kleinschmidt: The introduction of the potato in the Palatinate and the spread of potato dishes in the West Palatinate and in the adjacent areas of the former Rhine Province. Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde Münster, 1978, Vol. 24, No. 1–4, pp. 208–230.

- JHG Krombach: Flore du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Plantes phanérogames. Luxembourg 1875, 564 pp.

- D. Lauer: All about the potato. An entertaining foray through their history with a short potato chronology and a contribution by chef Michael Krämer. 2nd edition Kell am See 2001, 48 pp.

- F. Lorang: From all time: Gromperen. The waiting period, year 2002, no. 2 (January 17th), p. 2; No. 4 (January 31), oi = book_resultLuxemburg, p. 4.

- JA Massard: Le Doryphore et le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg (esquisse historique). Archives de l'Institut grand-ducal de Luxembourg, Section des sciences naturelles, physiques et mathématique, NS 43, Luxembourg 2000, pp. 175-217. ( PDF )

- JA Massard: 300 years of potatoes in Luxembourg: (I) Europe discovers the potato. (II) Grundbirne, Grompir, Gromper: the potato conquers Luxembourg. (III) The potato in Luxembourg in the 19th century. Lëtzebuerger Journal 2009, [I] No. 15 (Jan. 22): 23; No. 16 (Jan. 23): 10, No. 17 (Jan. 24/25): 11; [II] No. 18 (Jan 27): 23, No. 19 (Jan 28): 21; [III] No. 20 (Jan. 29): 9, No. 21 (Jan. 30): 21. PDF newspaper text with annotations. (PDF file; 345 kB)

- P. Modert: Bread made from flour and potatoes as well as sprouted grain. Letzeburger Bauere-Kalenner 32 (1980), pp 78-80, Luxembourg.

- Pierre Prüm: Fragments of Oeslinger local and regional history: Clergy knights, citizens and farmers in old times. Luxembourg (no year), 39 pp.

- FJ Nieth: The first potatoes in the Eifel. In: Eifeljahrbuch 1991, p. 66 (year of publication: 1990).

- Fernand Pirotte: La pomme de terre en Wallonie au XVIIIe siècle. Liège 1976, 87 pp. (= Collection d'études publiée par le Musée de la vie wallonne, 4).

- H. Rinnen: Gromper - "Solanum tuberosum". In: An der Ucht, 23 (1969), pp. 187-191, Luxembourg.

- Heinz Schmitt: Three centuries of potato cultivation in the Eifel. In: Heimatkalender Landkreis Bitburg-Prüm 2004, pp. 44–52 (year of publication 2003).

- Arthur Schon: Timeline of the history of the Luxembourg parishes from 1500–1800. Esch / Alzette, 1954/57, pp. 1–516, V.1 – V.166.

- Nicolas van Werveke:

- Cultural history of the Luxembourg country. New edition ed. by Carlo Hury. Vol. 1. Esch / Alzette 1983, 549 pages (reprint of the original edition in three volumes by the publisher Gustave Soupert, Luxembourg, 1923–1926).

- Cultural history of the Luxembourg country. New edition ed. by Carlo Hury. Vol. 2. Esch / Alzette 1984, 593 pages (reprint of the original edition in three volumes by the publisher Gustave Soupert, Luxembourg, 1923–1926).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 18; Lorang 2002.

- ↑ Jakob 1981, Massard 2009, No. 18. See also: Michel Wilhelm: The community Erpeldingen and its history. Vol. 1. Luxembourg 1999, p. 431.

- ↑ In the years after the outbreak of the potato blight, de la Fontaine personally participated in the introduction of new potato varieties in Luxembourg. He put z. For example, the comice d'Amiens variety was presented to the general public on the occasion of the agricultural fair in September 1851 after he had tested the variety in his own garden on Limpertsberg (cf. Fischer 1860: 135-136).

- ↑ In German: "Note about the potatoes and about the time of their introduction to the Luxembourg countryside and the Walloon Ardennes".

- ↑ van Werveke 1983, p. 224 f., 1984, p. 314.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 18; Hess 1960, p. 261 f. See also e.g. E.g. Prüm o. J., Blackes 1983.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 18; As early as 1954/57, p. 492.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 19. See also: A. Bauler: 300 years ago: The terrible winter of 1709. Lëtzebuerger Journal 2009, No. 7 (10./11 Jan.): 24 (id. In: D ' Klack 3/2008 (Gemeng Ierpeldeng), pp. 26-27 Archived copy ( Memento of the original from December 1, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ).

- ↑ Pirotte 1976: 14.

- ↑ A. Sprunck: From the village chronicle of Stadtbredimus in the 17th and 18th centuries. In: Stadtbredimus 1966: Xe fête du vin. Luxembourg, 1966, p. 161.

- ↑ G. Spedener: Ephemeris of the Luxembourg national and local history. Diekirch 1932, p. 112; Massard 2009, no.19.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 19. For the history of the potato in the German neighboring areas of Luxembourg see: Nieth 1990, Schmitt 2003, Lauer 2001, Kleinschmidt 1978.

- ↑ a b Massard 2009, No. 18.

- ↑ Pirotte 1976, p. 39.

- ↑ Pirotte 1976, p. 37. For the introduction of the potato into the Palatinate see: Kleinschmidt 1978.

- ↑ Pirotte 1976: 38.

- ↑ Krombach 1875, p. 331.

- ↑ Klein, 1897, p. 226.

- ^ H. Marzell: Dictionary of German plant names. Volume 2: Daboecia - Lythrum. Leipzig 1972, col. 776ff.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 19.

- ↑ Already 1954/57, p. 420.

- ↑ A. Sprunck: Études sur la vie économique et sociale dans le Luxembourg au 18e siècle. Tome I: Les classes rurales. Luxembourg 1956, p. 57.

- ↑ Haslinger 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Flammang 1986/1987, Massard 2009, No. 19.

- ↑ Jakob 1981, p. 29.

- ↑ Literally translated: French (potato).

- ↑ Literally translated: little mouse.

- ↑ See also: Modert 1980.

- ↑ a b c d e Massard 2009, No. 20.

- ↑ Massard 2009, No. 20.

- ↑ H. Philipps (1822): History of cultivated vegetables; comprising their botanical, medicinal, edible, and chemical qualities; natural history; and relation to art, science, and commerce. 2d ed., Volume II. London 1822, p. 89. [1]

- ↑ Lauer 2001: 44.

- ↑ Kalbersch 1854, p. 153.

- ↑ Kalbersch 1854, p. 155.

- ↑ 1 ohm = approx. 150 liters.

- ↑ Kalbersch 1854, p. 157f.

- ↑ Kalbersch 1854, p. 154.

- ↑ N. Nilles: Cholera, Potato Disease, Drought, Flood, Hailstorm, Earthquake and War, Taxation and Noth. An attempt at a common Christian discussion of the nature and causes of the great plagues of the present, as well as the means against it by Dr. N. Nilles, pastor of Tüntingen. Würzburg 1856, p. 26f. u. 31.

- ↑ Massard 2000, pp. 188 ff.

- ↑ Escher Tageblatt 1936, No. 147 (June 24), p. 3. [2]

- ↑ Massard 2000, pp. 190 ff.

- ↑ Escher Tageblatt 1936, No. 163 (July 13), p. 3. [3]

- ↑ Escher Tageblatt 1936, No. 155 (July 3), p. 4. [4]

- ↑ Massard 2000, p. 189.

- ↑ Massard 2000; JA Massard & G. Geimer: Initiation à l'écologie. Principes généraux de l'écologie et notions sur le milieu naturel luxembourgeois ainsi que sur lesproblemèmes de l'environnement au Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. 2nd edition. Luxembourg 1993, pp. 142-143.

- ↑ JF Gangler: Lexicon of the Luxembourg vernacular. Luxemburg 1847, p. 190. [5] Archived copy ( Memento of the original from June 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Krombach 1875, p. 200.

- ↑ J. Weber: Lezeburjesch-latein-fransesch-deitschen Dixionèr fun de Planzen. Recueil des Mémoires et Travaux publiés par la Société Botanique du G.-D. de Luxembourg, 12 (1887-1889), Luxembourg 1890, p. 64. ( PDF )

- ↑ Klein 1897, p. 478.

- ↑ Rinnen 1969, p. 188.

- ↑ EJ Klein: Botanical chats for my young friends: a plant every month. Luxemburg 1936, p. 35 (excerpt from: Morgenglocken 1935).

- ↑ H. Klees: Luxembourg animal names. Luxembourg 1981, p. 14.

- ^ Dictionary of Luxembourgish dialect . Luxembourg 1906. [6] .

- ↑ Luxembourg Dictionary , Vol. 2. Luxembourg 1962, p. 83.

- ^ N. Gredt: Legends of the Luxembourg country. Luxembourg 1883, 645, XVII S .; quoted from the 3rd edition, vol. 1. Esch-Alzette 1964, p. 424f. [7]