Sami languages

| Sami (Sámegiella) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Norway , Finland , Sweden and Russia | |

| speaker | approx. 24,000 | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | recognized as a minority language in individual municipalities in Finland , Norway and Sweden | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

smi (other Sami languages) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

- |

|

Sami (also Sami or Saami, in older literature also called Lappish ) is a group of closely related languages within the Uralic language family , which are spoken today by around 24,000 speakers, mainly in Sápmi . The language area stretches from central norway and sweden across northern finland to the kola peninsula in north - west russia . A relatively large number of speakers also live in the large cities of Scandinavia and Russia. Since the Sami see themselves as one people in four countries, they themselves often speak of "the Sami language", even when they refer to the whole group and mutual understanding between the speakers of different Sami languages is in most cases hardly possible. In older research, too, the various languages were mostly referred to as “dialects”.

Seven Sami languages have a lively written language today. Of these, North Sami is the most widespread and also best represented in the media.

history

Even if Sami is closely related to the Baltic Finnish languages, the genetic relationship between Sami and Finno-Ugrians is only slight, according to genetic studies (e.g. by Cavalli-Sforza ). Due to some major linguistic differences from Finnish and numerous words that are neither Finno-Ugric nor Germanic origin, it must be assumed that the Sami adopted the Finno-Ugric language from another, very small people, whose genetic traces are no longer verifiable are.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of the Sami languages was banned in state schools in all three Nordic countries and the Soviet Union due to the prevailing assimilation policy . The so-called “nomad schools” in Sweden were an exception. In Finland and Russia this ban was in place until the 1960s. For example, B. a Sami contemporary witness from Lowozero that every violation of the ban in the Soviet Union was rigorously punished. As a result, the East Sami languages in Russia, but also Ume and Pitesami in Sweden, are particularly threatened with extinction today. The stigmatization of the use of the Sami languages up to the middle of the 20th century and the later revival also explains why today many Sami of the older generation no longer speak their mother tongue, while younger people are actively learning some of the Sami languages and dialects again and even pass it on to their own children.

For the originally only spoken Sami languages, written languages were developed and the respective grammar codified into the 1970s and 1980s . In order to keep pace with social and technological developments, however, many words from the neighboring languages, especially Norwegian and Swedish , have been adopted as loan words and adapted to the Sami grammar.

Classification of languages

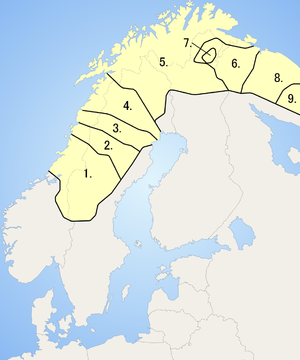

There are different classifications. Either a distinction is made between East Sami, Central Sami and South Sami, or the Sami languages are divided into a West and an East Sami group.

Western Sami

- South Sami (Norway, Sweden): approx. 700 speakers.

- Umesamisch (Sweden): approx. 20 speakers, almost extinct.

- Pitesamisch (Norway, Sweden): about 10 speakers, almost extinct.

- Lule Sami (Norway, Sweden): approx. 800 speakers, second largest Sami language.

- Northern Sami (Norway, Sweden, Finland): approx. 17,000 speakers, 70–80% of all Sami speakers.

Eastern Sami

- Skolt Sami (Finland / Russia): approx. 400 speakers.

- Inari Sami (Finland): 300–500 speakers.

- Kildin Sami (Russia): approx. 650 speakers.

- Tersamisch (Russia): approx. 20 speakers, almost extinct.

- Two other languages are already extinct:

- Akkalasami (Russia): The last female speaker of Akkalasami is said to have died in 2003. However, there are still at least two people who have passive language skills.

- Kemisamisch (Finland / Russia) has been extinct for over 100 years.

Written languages

In 2001 there were ten known Sami languages. Six of them were able to develop into written languages, the other four are hardly spoken any more, i. i.e. there are only less than 100 speakers. Since the individual languages or dialects are sometimes so far apart that communication between the speakers is impossible or difficult, North Sami enjoys the status of a lingua franca among the Sami. Most of the radio and television programs are broadcast in Northern Sami. The Sami languages use the Latin alphabet with the addition of diacritical marks and special letters , Kildin-Sami is written with Cyrillic letters.

Official status in Norway

In the constitution for the Kingdom of Norway, adopted in 1988, it is stated in Article 110a: "It is the task of the state organs to create conditions that enable the Sami to cultivate and develop their language, culture and way of life." A law on the Sami language came into effect in force in the 1990s. It declares the municipalities of Karasjok , Kautokeino , Nesseby , Porsanger , Tana and Kåfjord to be bilingual areas, which means that Sami is allowed to interact with the authorities.

Official status in Finland

The 1992 Language Act gave the Sami languages an official status in Finland in the so-called “homeland” of the Sami, which includes the municipalities of Enontekiö , Inari , Utsjoki and the northern part of the municipality of Sodankylä . North Sami is recognized in all four communities, in Inari also Inari Sami and Skolt Sami. This makes Inari the only quadrilingual community in Finland with three Sami languages and Finnish.

The status of the Sami languages guarantees the Sami the right to use it as a lingua franca in authorities and hospitals. All public announcements are made in Finnish and Sami in the Sami homeland. In the schools of some areas, North Sami is the primary school language .

Official status in Sweden

On April 1, 2002, Sami became one of the five officially recognized minority languages in Sweden. Sami can be used in official communications in the municipalities of Arjeplog , Gällivare , Jokkmokk and Kiruna , which means that every seed has the right to communicate in its own language with the authorities of the state and the commune and to receive an answer in its own language. Sami parents can choose whether they want to enroll their children in a Sami school with Swedish as a foreign language or vice versa.

In all three countries mentioned there are “parliaments” ( Sameting ), i.e. self-governing organs of the Sami, which, however, have no legislative function, but rather represent the Sami interests at the local level. In Sweden, the position of the Sami self-governing bodies is comparable in terms of their powers to that of the municipalities in Germany. For example, they can prevent interference with reindeer grazing areas (e.g. through hydraulic engineering projects), even if only temporarily. The resolutions of the Sami self-government can, however, be overruled if overriding interests or laws conflict with them.

Official status in Russia

The Russian Federation has about 145 million inhabitants. Of these, around 30 million are not ethnically Russian. The approximately 2000 Sami in Russia live on the Kola Peninsula and are heavily influenced by the Russian language and culture. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Soviet Union took measures to protect Sami culture. Shortly thereafter, 20 years of repression and Russification followed . The Kola Peninsula was important for industrial, economic and strategic reasons, which resulted in a large increase in population. Today more than 100 different ethnic groups live on the peninsula, which makes the approx. 2000 Sami a minority.

Until 2004, Kildin Sami was a compulsory subject at a school in Lowosero . This was replaced in 2004 by one voluntary lesson per week. Voluntary classes are offered in various locations, but the courses are aimed at beginners, are not offered on a regular basis, and have no permanent funding. In addition, there is a lack of teaching material and teaching aids for advanced and adults.

See also: seeds

Language code according to ISO 639

The ISO 639 standard provides for different language codes for the Sami languages. Depending on the defined goals of the respective sub-standards, a different set of languages is included.

North Sami, the largest of all Sami languages, has an entry with se in ISO 639-1, and with sme one each in ISO 639-2 and -3. The languages South Sami (with sma ), Lule (with smj ), Inari Sami (with smn ) and Skoltsamisch (with sms ) each have entries in ISO 639-2 and ISO 639-3. The rare or extinct languages are subsumed in ISO 639-2 under the entry other Sami languages with smi . ISO 639-3 codes are as follows: Umesamisch sju, Pitesamisch sje, Kildinsamisch sjd, Tersamisch sjt, Akkalasamisch sia and Kemisamisch sjk .

literature

- Barruk Henrik: Samiskan i Sverige - Report från Språkkampanjrådet . Sametinget, Storuman 2008 (Swedish, online ).

- Bettina Dauch: Sami for Lapland. Word by word. (= Gibberish . Band 192 ). Reise Know-How Verlag Rump, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89416-360-7 .

- Eckart Klaus Roloff : Lapland's neglected literature. In: Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel, Volume 42, 1986, No. 30, pp. 1050-1053, ISSN 0340-7373 .

- Veli-Pekka Lehtola: The Sámi: Traditions in Transition. Puntsi, Inari 2014.

- Wolfgang Schlachter : The Lappish literature. In: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon, Volume I. Zweiburgen Verlag, Weinheim 1984, pp. 534-538.

Web links

- The Saami in the Society for Threatened Peoples

- Dieđalaš áigečála - the only peer-reviewed magazine in a Sami language

- News in Sami Norwegian Broadcasting NRK

Individual evidence

- ↑ Larisa Avdeeva: History and current situation of the Saami in Lujavr (Lovozero). (1999) in: Wolf-Dieter Seiwert (Ed.): Die Saami. Indigenous people at the beginning of Europe. German-Russian Center, Leipzig 2000. pp. 55–56.

- ↑ a b Elisabeth Scheller (2011): The Sami Language Situation in Russia. In: Ethnic and Linguistic Context of Identity: Finno-Ugric Minorities. Uralica Helsingiensia 5. Helsinki. 79-96 (English).

- ↑ Leif Rantala & Aleftina Sergina: Áhkkila sápmelaččat . Rovaniemi 2009.

- ↑ See Kola Saami Documentation Project (in English).

- ^ Eckart Klaus Roloff: Sámi Radio Kárašjohka - mass medium of a minority. The radio broadcaster in the Norwegian part of Lapland. In: Rundfunk und Fernsehen, Volume 35, 1987, Issue 1, pp. 99-107, ISSN 0035-9874 .

- ^ Elisabeth Scheller: The Sámi Language Situation in Russia . In: Riho Grünthal, Magdolna Kovács (Ed.): Ethnic and Linguistic Context of Identity: Finno-Ugric Minorities . Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura, Helsinki 2011, p. 79-96 .