Herero

The Herero (singular; actually OvaHerero or Ovaherero ) are a Southwest African former shepherd people who speak the Bantu Otjiherero language and now number around 120,000 people. The majority of them live in Namibia , some also in Botswana and Angola .

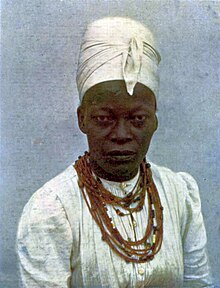

description

In Namibia, Herero earn their living mostly as workers on large farms or in the cities as traders and craftsmen, while the Herero who have spread to Angola live very traditionally as shepherds. A people often treated as a subgroup are the Ova Himba who live in the Kaokoveld and in the southern Angolan province of Namibe . The assignment of the Angolan mundimba and vakuval (e) is not completely clear, but is mostly assumed.

After they had immigrated to what is now Namibia in the 17th century and pushed the locals south, there were long and costly disputes with Nama and Orlam - Africans . During the German colonial committed the German occupying force under the guidance Lothar of Trothas a genocide of the Herero in which an estimated 65,000 to 85,000 Herero died (about 80 percent of the people Hereroland).

The OvaHerero in Namibia are divided into three main groups:

- White Flag (Zeraeua Royal House)

- Red flag (Maharero or Tjamuaha / OtjikaTjamuaha Royal House)

- Green Flag (Ovambanderu)

history

16th to 19th century

In the middle of the 16th century, the Herero immigrated - probably together with the Ovambo , with whom at least a certain linguistic affinity can be proven - from Central Africa to the Bechuanaland (today's Botswana). There they separated from the agricultural Ovambo , who in turn moved further west to the Kunene . As a result of disputes with the Batswana , the Mbandu separated : Some of them migrated as Herero to the north of what is now Namibia in the 17th and 18th centuries and initially settled there south of the Kunene , in the Kaokoveld . The Mbandu remaining in the Bechuanaland moved to the extreme western border of the country, which at that time extended to what is now Okahandja . This part of the population is called Mbanderu or Ostherero . At the end of the 18th century, Okahandja became the center of the Herero people. Tjamuaha is the guardian of the ancestral fire and thus chief chief of all Herero .

As a result of a long period of drought around 1830, the cattle-breeding Herero (Herero originally means cattle owner) expanded their pastures more and more to the south, displacing the Nama, who had settled there since 1700 . At the beginning of the 19th century, the Orlam , who were advancing from the South African Cape Colony , especially the Africans under their chief Jonker Afrikaner , came to their aid. Together, the Nama and Orlam succeeded in pushing the Herero back to around Windhoek .

The 19th century in Namibia was marked by constant disputes and mutual raids between the Herero on the one hand and the Nama and Orlam on the other. This warlike development was significantly promoted by the dealers who came to the country with the support of the missionaries : In addition to alcohol, they mainly sold firearms and took cattle in exchange for them. Extreme trade margins and high lending rates quickly impoverished the tribes and sparked numerous forays between the tribes to allow the chiefs to pay their debts. The Orlam Africans were the most successful in this - they succeeded in the almost complete extermination of the Herero in the middle of the 19th century (cf. Vedder: Das alten Südwestafrika , p. 369: “As far as we know, the Herero people have ceased to exist. ")

It was only after the death of the African chief Jonker Afrikaner in 1861 that the Herero managed to return under their chief Maharero in cooperation with the Swedish entrepreneur Karl Johan Andersson and his "private army" and the " Red Nation of Hoachanas " (Nama), who lived in Otjimbingwe to old strength and consequently in 1870 a complete submission of the Orlam Africans ( 10-year peace of Okahandja ).

German colonial times

At the end of the 19th century, the first Europeans aspiring to permanent settlement came to the country. In Damaraland as well as in the central highlands around the city of Windhoek, German settlers bought land from the Herero to build farms. In 1883, the businessman Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz signed a contract with local tribal elders, which later became the basis for German colonial rule. Southwest Africa became a German colony (formally a German protected area ) under the name Deutsch-Südwestafrika ( German South West Africa) in 1884 after recognition by the British Crown .

Despite the initially good understanding between the German colonial administration and the Herero, conflicts soon arose between the German colonialists and the Herero herders. This often involved land and water rights (for example in connection with the construction of the Otavi Railway , Lüderitz had also bought several miles of land from them and concealed from them that the contract was about nautical miles), but also (for Example legal) discrimination (such as unpunished sexual assaults on Herero women), proselytizing , oppression and exploitation of the natives by the whites. The year 1897 in particular had a devastating effect: the rinderpest coming from South Africa and a large plague of locusts led to the loss of almost 70% of the Herero's livestock. This and the credit sales forced by the traders led to a lasting impoverishment of the Herero and forced them to sell more land and to work with German farmers.

These conflicts resulted in the Herero uprising in January 1904, triggered by the clumsiness of the German district chief in Okahandja, Lieutenant Ralf Zürn, which began with the sacking of the city of Okahandja under the leadership of Chief Samuel Maharero . The preliminary planning was done by exchanging letters between the tribal leaders, some of the documents are still preserved today.

The Herero's initial military strikes against the colonists included the burning of all farms and settlements in their area, with around 150 German settlers, mostly men, being murdered. Since the Herero had given the order to spare missionaries , they were later falsely accused of collaboration.

After initially successful attack the well organized and equipped with firearms insurgent army against the numerically far inferior because of a "minor uprising of Bondelswarte" in the south-bound protection force under Governor Theodore Leutwein sent the German Reich an expeditionary force under Lothar von Trotha with about 15,000 men, which the Herero quickly pushed back with targeted use. The tactically superior approach of Lothar von Trotha, with the intention of realizing the annihilation of the entire Herero people, resulted in the first genocide of the 20th century, which killed up to 80 percent of the Herero people, i.e. up to 80,000 Herero.

The Germans looked for the decision at the Waterberg . The Herero lost the Battle of Waterberg on August 11, 1904, but many Hereros were able to flee to the waterless Omaheke steppe. The German protection force and the Orlam-Witbooi allied with them sealed off the desert and drove the Hereros from the water points. Women and children were expressly denied the opportunity to surrender to the German soldiers.

Between 25,000 and 100,000 Herero and 1749 Germans perished during the war and afterwards. Only about 1000 Herero managed to escape to Bechuanaland with their chief Samuel Maharero, an unknown number came through to the north and were taken in by the Ovambo. Some Herero returned exhausted and discouraged and surrendered.

The Witbooi fighting on the German side were appalled by the extent of the annihilation, and some fled because they feared a similar fate. After the outbreak of the Nama uprising , the remaining Witbooi mercenaries were disarmed and deported as work slaves to the German colonies of Cameroon and Togo , where the majority of them perished.

In the following years, individual Herero divisions fought alongside the rebellious Nama.

In Bechuanaland, the surviving Herero led a minority existence under their chief Samuel Maharero. Maherero died in exile in 1923, was transferred to Okahandja on August 23, 1923 and buried there with great ceremonies under the direction of the new Herero chief Hosea Kutako .

Aftermath of the genocide

To commemorate the Battle of Waterberg and the Herero chiefs Tjamuaha , Maharero , Samuel Maharero and Hosea Kutako who were buried in Okahandja, the so-called Herero Day is celebrated every year in August with a focus on Okahandja . It is a day of commemoration carried by the tribal consciousness of the Herero and based on their ancestral cult .

On the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Waterberg in August 2004, the German Minister for Development Cooperation Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul also commemorated the dead on site and admitted for the first time the political and moral guilt of the German colonial administration. Since July 10, 2015, the federal government has recognized the events of that time as genocide .

In 2011, Herero applied for the return of the Herero skulls that had been exported to Germany for pseudoscientific research purposes in the course of the colonial occupation and the genocide . Many of these skulls are still stored in the Berlin Charité , at the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory and in Freiburg university buildings. In November 2011, a Herero delegation received the first skulls in the Charité and transferred them to Namibia. In 2014 there was a second handover in the Charité and also a first handover from Freiburg's holdings. In August 2018 there was another handover of bones as part of a memorial service. During the ceremony, the Protestant bishop Petra Bosse-Huber demanded that the genocide be recognized as genocide. Minister of State Michelle Müntefering handed over the bones to the Namibian delegation.

More details on this topic: see Genocide and the Federal Republic of Germany .

The Herero in Angola

In contrast to Namibia, the history of the Herero in Angola is not very dramatic. As shepherds, they have chosen a settlement area north of Namibia in what is now the Namibe Province , in which there were otherwise only small scattered Khoisan groups. There they led and still lead the lives of nomads or semi-nomads. They barely resisted the occupation of this part of Angola by the Portuguese at the beginning of the 20th century. On the other hand, they were hardly bothered by the colonial rulers, who had little interest in the Namib Desert and its sparse inhabitants. The Vakuval were even happy to be able to find seasonal work in the area of today's city of Moçâmedes , which gave them the opportunity to connect to the money economy, which was slowly expanding. They did not take part in the anti-colonial guerrilla war in Angola (1961–1974).

When the armed conflict between the three liberation movements broke out in 1974/75, the MPLA provided the Vakuval with a modest contingent of weapons to use against FNLA and UNITA in the battle for Lubango - in which, however, in the end they practically did not take part. After Angola's independence (1975), the Herero groups continued their way of life as usual. From the civil war in Angola (1975-2002), they were barely touched, not even through the establishment of base camps of SWAPO in the southwest of Angola.

So far they have hardly been impressed by the economic development of Angola, some of which has now also reached this part of the country - in contrast to their neighbors, the Nyaneka-Nkhumbi . They continue to take part in overarching economic cycles only to a limited extent, only make limited use of opportunities for schooling for their children and for health care and remain largely immune to attempts at proselytizing.

See also

literature

- Rachel Anderson: Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law- The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany. 93 CALIF. L. REV. 1155 (2005)

- William Gervase Clarence-Smith: Slaves, Peasants and Capitalists in Southern Angola, 1840-1926. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979

- Horst Drechsler : South West Africa under German colonial rule. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin (GDR), 1984

- Ruy Duarte de Carvalho: Eu fui lá visitar pastores. Gryphus, Rio de Janeiro 2000 (to the Vakuval)

- Dag Henrichsen: Rule and everyday life in pre-colonial central Namibia; The Herero and Damaraland in the 19th century (dissertation), Basel / Windhoek 2011, CH- ISBN 978-3-905758-23-8 ; NAM- ISBN 978-99916-40-98-3

- Júlio Artur de Morais: Contribution à l'étude des écosystèmes pastoraux: Les Vakuval du Chingo. Doctoral thesis, Paris: Université de Paris VII, 1974

- Toubab Pippa: The malice in the heart of the people - Hendrik Witbooi and the black and white history of Namibia. Green Kraft Verlag, ISBN 3-922708-31-5

- José Redinha: Etnias e culturas em Angola. Instituto de Investigação Científica de Angola, Luanda 1975

- Helmut Rücker, Gerhard Ziegenfuß: A skull from Namibia - head held high back to Africa . 3. Edition. Anno-Verlag, Ahlen 2018, ISBN 978-3-939256-75-5 .

- Theo Sundermeier: The Mbanderu. Studies of their history and culture. Anthropos Institute, St. Augustin 1977

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ See the standard work by Carlos Estermann, Etnografia do Sudoeste de Angola , 3 vols., Lisbon: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1956

- ↑ Medardus Brehl: "These blacks deserve death before God and people" The genocide of the Herero 1904 and its contemporary legitimation . In: Irmtrud Wojak, Susanne Meinl (ed.): Genocide. Genocide and War Crimes in the First Half of the 20th Century . Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 77–97 (= yearbook on the history and effects of the Holocaust 8)

- ↑ Manfred O. Hinz: Customary Law Ascertained Volume 3: The Customary Law of the Nama, Ovaherero, Ovambanderu, and San communities of Namibia. UNAM Press, Windhoek 2016, ISBN 978-99916-42-12-3 , pp. 286ff.

- ↑ Dominik J. Schaller: “I believe that the nation as such must be destroyed”: Colonial war and genocide in “German South West Africa” 1904–1907. In: Journal of Genocide Research . 6: 3, p. 398

- ^ German Embassy Windhoek: Speech by Federal Minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul on August 14, 2004 in Okakarara ( Memento from July 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ German colonial crimes: German government calls Herero massacre "genocide" for the first time, Spiegel Online, July 10, 2015.

- ↑ deutschlandfunk.de: Colonial Skeleton Collections - Corpses in the Basement , accessed on October 12, 2015

- ↑ Germany returns bones to Namibia. Time online, August 29, 2018, accessed August 31, 2018 .

- ↑ On a brief and late flare-up among the Vakuval see René Pélissier , Les guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845–1941) , Montaments / Orgeval: Selbstverlag, 1977

- ↑ Oral information from the Angolan agronomist Júlio Artur de Morais, who did his doctorate on the vakuval and was then in the province of Huíla .