Bantu languages

| Bantu languages | ||

|---|---|---|

| speaker | 200 million | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 | ||

| ISO 639 -5 |

bnt |

|

The Bantu languages form a subgroup of the Volta-Congo branch of the African Niger-Congo languages . There are around 500 Bantu languages spoken by around 200 million people. They are widespread throughout central and southern Africa , where they are the most widely spoken languages in all countries, even though English , French or Portuguese are usually used as official languages .

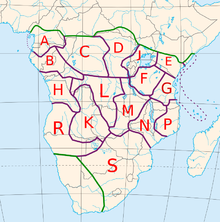

In the north-west the Bantu region borders on the other Niger-Congo languages, in the north-east on Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asian (more precisely Semitic and Cushitic ) languages. In the southwest, the Khoisan languages form an enclave within the Bantu area (see map).

The science of the Bantu languages and the cultures and peoples associated with them is called Bantuistics . It is a branch of African Studies .

The word Bantu

The word "bantu" means "people" in the Congo language . It was introduced into the linguistic discussion by WHI Bleek in 1856 as a term for a widespread African language group whose languages share many common characteristics. Above all, this includes a pronounced system of nominal classes (see below), but also extensive lexical similarities. The following table shows the word for "human" - singular and plural - in a selection of important Bantu languages:

| language | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

|

Congo , Ganda , Rwanda , Zulu |

mu-ntu | Bantu |

| Herero | mu-ndu | va-ndu |

| Lingála | mo-to | ba-to |

| Sotho | mō-thō | bā-thō |

| Swahili | m-do | wa-tu |

Singular and plural are apparently formed by the prefixes mu- and ba- . In fact, these are the first two nominal classes (see below) of almost all Bantu languages that denote people in the singular or plural. The hyphens are not written in the normal written rendering of Bantu words, but are used throughout this article for clarity.

The most speaker-rich Bantu languages

The best known and as a common language spoken most often Bantu language is Swahili (also Swahili, Kiswahili or Swahili). The following table contains all Bantu languages with at least 3 million speakers and indicates the number of their speakers, their classification within the Guthrie system (see below) and their main distribution area. Some of these languages are so-called vehicular languages that are not only native speakers to learn (as a first language), but by many speakers as a second- be purchased or third language, a communication to enable a wider area across language borders of individual ethnic groups away.

| language | Alternative name | Number of speakers (in millions) | Guthrie Zone | Main distribution area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swahili | Swahili, Kiswahili | 75-80 | G40 | Tanzania , Kenya , Uganda , Rwanda , Burundi , Congo , Mozambique |

| Shona | Chishona | 11 | S10 | Zimbabwe , Zambia |

| Zulu | Isizulu | 10 | S40 | South Africa , Lesotho , Swaziland , Malawi |

| Nyanja | Chichewa | 10 | N30 | Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique |

| Lingala | Ngala | 9 | C40 | Congo , Congo-Brazzaville |

| Rwanda | Kinyarwanda | 8th | J60 | Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Congo |

| Xhosa | Isixhosa | 7.5 | S40 | South Africa, Lesotho |

| Luba Kasai | Chiluba | 6.5 | L30 | Congo |

| Gikuyu | Kikuyu | 5.5 | E20 | Kenya |

| Kituba | Kutuba | 5 | H10 | Kongo, Kongo-Brazzaville (Congo-based Creole language ) |

| Ganda | Luganda | 5 | J10 | Uganda |

| Rundi | Kirundi | 5 | J60 | Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda |

| Makhuwa | Makua | 5 | P30 | Mozambique |

| Sotho | Sesotho | 5 | S30 | Lesotho, South Africa |

| Tswana | Setswana | 5 | S30 | Botswana , South Africa |

| Mbundu | Umbundu | 4th | R10 | Angola ( Benguela ) |

| Pedi | Sepedi, North Sotho | 4th | S30 | South Africa, Botswana |

| Luyia | Luluyia | 3.6 | J30 | Kenya |

| Bemba | Chibemba | 3.6 | M40 | Zambia, Congo |

| Tsonga | Xitsonga | 3.3 | S50 | South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe |

| Sukuma | Kisukuma | 3.2 | F20 | Tanzania |

| Kamba | Kikamba | 3 | E20 | Kenya |

| Mbundu | Kimbundu | 3 | H20 | Angola ( Luanda ) |

- ↑ a b c d e f "Congo" stands for the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- ↑ a b "Congo-Brazzaville" for the Republic of the Congo

The class prefixes for language names (e.g. ki-, kinya-, chi-, lu-, se-, isi- ) are usually no longer used in linguistic literature. In this article, too, the short form is used without a prefix, e.g. B. Ganda instead of Luganda .

There are numerous other Bantu languages with more than 1 million speakers. The appendix "Bantu languages according to Guthrie zones" at the end of this article provides an overview of all Bantu languages with at least 100,000 speakers.

Research history and current position of the Bantu languages

Overview of the research history

As early as 1659, Giacinto Brusciotto published a grammar of the Congo language written in Latin . Wilhelm Bleek first described the nominal classes of the Bantu languages in 1856 (see below) and coined the term Bantu . Carl Meinhof developed her first comparative grammar (1901). Malcolm Guthrie classified them in 1948 and divided them into 16 geographical zones from 1967–71, which he designated with the letters A – S (without I, O, Q). Within these zones, the languages are grouped and numbered in units of ten (see: Classification of the Bantu languages according to Guthrie). Guthrie also reconstructed the Proto-Bantu as the hypothetical predecessor language of all today's Bantu languages. Joseph Greenberg classified the Bantu group as a sub-sub-unit of the Niger-Congo languages (see below). Before that, the Bantu languages, especially by Carl Meinhof and his students, were viewed as a separate language family , which were contrasted with the Sudan languages in the distribution area of the black African languages .

Development of theories about the origin of the Bantu languages

Numerous linguists have been concerned with the question of the origin ( original home ) and emergence of the Bantu languages since 1860. Some historically important hypotheses are listed here to illustrate the difficult process leading up to today's explanation of Bantu as a sub-unit of the Niger-Congo languages .

Richard Lepsius

In the introduction to his Nubian grammar in Africa in 1880, the Egyptologist Richard Lepsius assumed three language zones, ignoring the Khoisan group: (1) Bantu languages in southern Africa, the language of the actual " Negroes ", (2) mixed " Negro languages ”between the equator and the Sahara, the Sudan languages , (3) Hamitic languages ( Egyptian , Cushitic , Berber ) in northern Africa.

The primary characteristics of these language groups are the class system of the Bantu and the gender system of the Hamites , who immigrated from West Asia to Africa. As a result of their penetration, they pushed parts of the previous population to South Africa (the Bantu, who kept their "pure" form of language); other groups mixed with the Hamites and formed mixed languages - the Sudan languages - which had neither a pronounced class nor enjoyment system. He described their grammar as "shapeless", "receded" and "defoliated".

August Schleicher

The Indo-Europeanist August Schleicher had a completely different idea, which he published in 1891. In his opinion, Africa was initially uninhabited and was populated from Southwest Asia in four great waves:

- the "Bushmen" (actually San ) and " Hottentots " (actually Khoikhoi )

- the "Negro peoples" of Sudan , the so-called "Nigrites"

- the Bantu

- the " Hamites ".

He assumed that the Sudanese nigrites had already had a rudimentary, imperfect class system that the Bantu peoples then perfected and developed. For him, then, Nigritic or Sudanese was an evolutionary forerunner of Bantu, and not a result of the disintegration as with Lepsius.

Carl Meinhof

The Africanist Carl Meinhof made several comments between 1905 and 1935 about the emergence of the Bantu languages; it stands in clear contrast to the hypotheses of Lepsius and Schleicher. For him it is not the Bantu language, but the Sudan languages that are originally Nigritic. Bantu is a mixed language with Nigritic “mother” ( substrate ) and Hamitic “father” ( superstrate ). According to Meinhof, Africa was settled in three linguistic layers: (1) the Nigritic Sudan languages , (2) the Hamitic languages and (3) the Bantu languages as a hybrid of Nigritic and Hamitic.

Diedrich Westermann and Joseph Greenberg

As a Meinhof student, Diedrich Westermann initially assumed that the Sudan and Bantu languages had a common nigritic substrate . From 1948 onwards, however, he was increasingly convinced of the original genetic relationship between the Western Sudan languages and the Bantu languages, as he has shown in several publications. In doing so, he prepared the ground for Greenberg's Niger-Congo approach.

Joseph Greenberg consistently continued Westermann's approaches and established the Niger-Congo phylum in 1949 as a large language family in western and southern Africa, which includes the Bantu languages and which emerged from a western Sudanese "nigritic" core. The structure of this family has changed several times since this initial approach; the last Greenberg version is his work "Languages of Africa" from 1963.

Even after Greenberg, the internal structure of the Niger-Congo phylum was changed several times (see Niger-Congo languages ), but all versions - including the current ones (e.g. Heine-Nurse 2000) - agree that the Bantu languages represent a sub-sub-unit of the Niger-Congo, which are most closely related to the so-called bantoid languages of eastern Nigeria and western Cameroon .

The position of the Bantu languages within the Niger-Congo

The following figures show the great importance of the Bantu languages within the Niger-Congo languages (and thus in the context of African languages in general):

- Of the approximately 1,400 Niger-Congo languages, 500 belong to the Bantu group; that's more than a third.

- Of the roughly 350 million speakers of a Niger-Congo language, 200 million - almost 60% - speak a Bantu language.

Nevertheless, according to today's knowledge, which is mainly based on the work of Joseph Greenberg , the Bantu group is only a sub-sub-unit of the Niger-Congo. The exact position of the Bantu group within the Niger-Congo languages shows the following somewhat simplified genetic Diagram:

Position of the Bantu within the Niger-Congo

-

Niger-Congo

- Kordofan

- Mande

- Atlantic

- Dogon

- Ijoid

- Volta Congo

- North Volta Congo

- Kru

- Gur (Voltaic)

- Senufo

- Adamawa-Ubangi

- South Volta Congo

- Kwa

- Benue Congo

- West Benue Congo

- East Benue Congo

- Platoid (Central Nigerian)

- Bantoid Cross River

- Cross river

- Bantoid

- Northern Bantoid

- Southern bantoid

- various smaller groups

- Grasslands

- Bantu

- North Volta Congo

The complex lineage of the Bantu languages is thus with all the intermediate links:

-

Niger-Congo > Volta-Congo> South-Volta-Congo> Benue-Congo> East-Benue-Congo>

Bantoid - Cross River> Bantoid> South Bantoid> Bantu .

For a detailed classification of the Bantu languages within the Guthrie groups, including the number of speakers, see the section at the end of the article "Bantu languages according to Guthrie zones" (for languages with at least 100,000 speakers) and the web link given below (for all Bantu languages).

Original home and expansion

All theories about the origin of the Bantu languages make explicit or implicit statements about their original home and later spread to the present-day settlement areas of the Bantu peoples.

Original home of the Bantu languages

According to his classification - Bantu as a subgroup of the bantoid languages otherwise widespread in Nigeria and Cameroon - Joseph Greenberg put the original home of the Bantu languages in the middle Benue Valley (eastern Nigeria ) and in western Cameroon. That is the opinion that is accepted and held by most researchers today.

Malcolm Guthrie, on the other hand, still expressed in 1962 on the basis of a word-fact argument (connection between archaeologically tangible objects or cultivated plant species and the linguistic names for them) that Proto-Bantu developed in an area southeast of the equatorial tropical rainforest . Star-shaped migrations have taken place from this core area into today's settlement areas. He solved the problem of the related bantoid languages in distant West Africa by assuming that some pre-Bantu groups had penetrated the jungle with the help of boats to the north. Guthrie's position no longer plays a role in today's research; generally one is original homeland of the Bantu north accepted the tropical rainforest, the vast majority agrees Greenberg's approach Eastern Nigeria-West Cameroon to.

Expansion of the Bantu peoples

Western and Eastern routes of expansion

The expansion of the Bantu peoples from their original West African homeland into all of Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the greatest migratory movements of humanity. On the question of which paths the Bantu groups have now taken from their original home, there are two theories that are not mutually exclusive, but only set different priorities. The first states (e.g. Heine-Hoff-Vossen 1977) that the early Bantu migrated mainly close to the coast "past the rainforest to the west", another grouping on the northern edge of the rainforest first migrated to the east and then south. The western main group then formed a new nucleus on the lower reaches of the Congo , from which the majority of the Bantu tribes in the savannah and in the East African highlands emerged. The second theory is mainly based on a northern bypass of the rainforest. These groups then later moved south from the area of the great East African lakes and then formed the Congo nucleus (or united with it), from which the further settlement of Southeast and South Africa took place. In general, one assumes early western and eastern Bantu groups, which correspond to the two main hiking trails.

Chronology of the spread

According to Vansina (1995) and Iliffe (1995) one can use the reconstructed Proto-Bantu vocabulary (agriculture, ceramic production ), the archaeological finds (especially ceramics) and the products used for agriculture by early Bantu groups ( oil palm , yams , but still no grain) conclude that the first emigration from the original West African homeland in eastern Nigeria must have occurred after the introduction of agriculture and pottery. From the archeology of East Nigeria and West Cameroon, the probable period is around 3000-2500 BC. BC as the beginning of the emigration movement. First, the early Bantu migrated to the Cameroon grasslands, where other terms for agriculture , livestock ( goat , cattle ), fish farming and boat building enriched the vocabulary.

1500-1000 BC Then there was a migration of Bantu groups west of the drier rain forest to the south to the lower reaches of the Congo . There Bantu cultures are archaeologically around 500–400 BC. Chr. Tangible. They didn't know any metalworking yet . Some of these groups migrated further south to northern Namibia , others swiveled to the east, moved through the great river valleys and united with the eastern group in the Congo nucleus (see below).

The (probably larger) eastern group moved from 1500 BC. From Cameroon along the northern edge of the rainforest to the area of the great lakes of East Africa. There are from 1000 BC Evidence for the first grain cultivation ( sorghum ), intensive animal husbandry and - from 800 BC BC - first archaeological evidence of metal processing and iron production ( smelting furnaces in Rwanda and Tanzania ). Terms for metals and metal processing are also linguistically reflected in Proto- West -Bantu, while Proto-Bantu did not yet know them. Possibly this cultural upswing of the Bantu peoples in agriculture, cattle breeding and metal processing was due to the influence of Nilo-Saharan groups from the upper Nile valley , where this cultural stage was reached much earlier. The Bantu peoples obviously represent the core of the Iron Age Urewe culture , which was widespread in the area of the great East African lakes. The more intensive agricultural use due to slash and burn and the need for firewood for iron production is accompanied by extensive deforestation of the forests in the East African lake area, i.e. the first large-scale transformation of nature in Africa by man.

From the area of the great lakes, the Urewe-Bantu (as evidenced by their specific ceramics) moved from around 500 BC. Gradually in all areas of East and South Africa. Urewe pottery is on the Zambezi from 300 BC. Demonstrable. In the first century AD Angola , Malawi , Zambia and Zimbabwe are reached, in the 2nd century Mozambique , and finally South Africa around 500 AD . Sedentary lifestyles (with fallow land -Rekultivierung) were the Bantu peoples until 1000 n. Chr. From, before she forced the slash and burn technique to constant Weiterzug and the task of the leached surfaces.

The pressure of the Bantu peoples had to give way to the Khoisan , who then settled much larger areas of South Africa than they do today. The desert and steppe zones of southern Angola , Namibia and Botswana , which were unsuitable for growing sorghum and therefore useless for the Bantu, became their retreat . The ethnic groups grouped together as " pygmies " probably also inhabited larger contiguous areas of Central Africa before they were pushed back into a few smaller areas by the Bantu. Today they speak the languages of the respective neighboring Bantu peoples, but with some phonetic and lexical peculiarities that may go back to their own earlier languages.

Linguistic characteristics

Despite their distribution over a vast area, the Bantu languages show a high degree of grammatical similarity. Particularly characteristic are the formation of noun classes - all nouns are divided into ten to twenty classes depending on the language, the class of the noun is indicated by a prefix - the influence of these classes on the congruence or concordance of all grammatical categories (i.e., the class of the noun carries over to its attributes and those of the subject to the forms of the predicate ) as well as complex verbal forms that are similarly constructed in all languages . Both nominal and verbal formation are essentially agglutinative ; both prefixes and suffixes are used.

The Bantu languages share a large common vocabulary , so that several hundred Proto-Bantu roots could be reconstructed, the descendants of which occur in almost all zones of the Guthrie scheme. In the Bantu languages, parts of speech are to be distinguished according to their syntactic usage, not according to their external form. In addition to the nouns and verbs already mentioned, there are relatively few independent adjectives (most of them are derivatives of verbs ), an incomplete system of numerals (7, 8, and 9 are usually foreign words ) and a rich inventory of pronouns , with the demonstrative pronouns can express up to four different levels of near and far (“this”, “that” and others).

The syntax is strongly morphosyntactically determined, in particular by the nominal class system and the associated concordance in the noun phrase and between subject and predicate . The usual word order is subject - predicate - object (SVO).

Phonology

Historically, the Bantu languages have simple phonetics . The words consist of open syllables , plosives can pränasaliert (e. B. mb- or nd- ). The consonant inventory originally consisted of unvoiced , voiced , nasal and prenasal plosives : / p, b, m, mp, mb; t, d, n, nt, nd /, further it contained / tʃ / . These phonemes were largely preserved in today's Bantu languages. Protobantu obviously had no other fricatives , but / s, ʃ, z, h, f, v / are widespread in modern Bantu languages . Thus obtained following consonant inventory, but do not possess all the phonemes of the individual languages (eg. As / ts / or / tʃ / , / dz / or / dʒ / ; Pränasalreihe 1 or 3, 2 or 4):

| Consonants | labial | alveolar | palatal | velar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless plosives | p | t | . | k |

| voiced ejectives | b | d | . | G |

| voiced implosives | ɓ | ɗ | . | ɠ |

| Affricates | . | ts / dz | tʃ / dʒ | . |

| Approximants | β | l | . | ɣ |

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ |

| Prenasalized 1 | mp | nt | . | ŋk |

| Prenasalized 2 | . | nts | ntʃ | . |

| Prenasalized 3 | mb | nd | . | ŋg |

| Prenasalized 4 | . | ndz | ndʒ | . |

The ejectives correspond to the German pronunciation of b , d and g . The implosive sounds - in Swahili three, in Shona two, in Xhosa and Zulu only the ɓ - are usually reproduced in writing with their ejective counterparts. These are sometimes differentiated orthographically, for example by adding an h.

Some southern Bantu languages have also adopted their click sounds through contact with Khoisan languages . This mainly applies to languages of Guthrie groups S40 and S50, especially Zulu (12 clicks) and Xhosa (15). But Yeyi (or Yeye) (R40) also has up to 20 clicks, while closely related and neighboring languages that have had contact with the Khoisan languages (e.g. Herero ) show no traces of clicks. This is probably due to the fact that the Herero came into contact with the Khoisan languages much later than the Xhosa and other peoples living east of the Kalahari.

The Protobantu vowel system consisted of the seven vowels / i, e, ɛ, a, ɔ, o, u /. It is still preserved today in the north-east and north-west central Bantu languages, while in the remaining (around 60%) it was reduced to the five vowels / i, ɛ, a, ɔ, u /. In a number of recent Bantu languages, the differences between long and short vowels are also phonemically relevant. Whether it is a property of the Protobantu or an innovation in certain subgroups has not yet been decided.

The Protobantu was certainly a tonal language , which means that the pitch of a syllable is meaningful. A large part of the Bantu languages (97% according to Nurse 2003) have retained this characteristic. Most Bantu languages have no more than two differentiating tones , which can be characterized as either high-low or high-neutral . But there are also more complex systems with up to four different pitches. A few languages, including Swahili, have lost their tonal differentiation.

There is some form of vowel harmony in some Bantu languages that affects the vocalization of certain derivative suffixes. For example, in Gikuyu, the reverse suffix -ura behind the verbal root hung ("open") has the form hung-ura ("close"), but behind the verb oh ("bind") it has the form oh-ora ("untie"). A dissimilation of initial consonants of the nominal class prefix and the nominal stem shows the language name Gi-kuyu , which should be regularly formed Ki-kuyu (the spelling Kikuyu is wrong).

The accent is in most Bantu languages on the penultimate syllable .

Nominal morphology

Nominal classes

A special feature of the Bantu languages is the division of nouns into so-called classes . However, they share this characteristic with a large number of other Niger-Congo languages and also with languages of completely different genetic origins, e.g. B. Caucasian , Yenisian or Australian languages. The assignment of a noun to a class was originally based on the meaning category of a word, but it often appears randomly in today's Bantu languages. The grammatical gender z. B. in many Indo-European languages can be interpreted as a class division (so one could understand Latin as a 6-class language: masculine , feminine and neuter , each in the singular and plural ).

There were about twenty classes in the Protobantu . This number has been retained in some of today's Bantu languages (e.g. in Ganda ), in others it has been reduced to around ten classes. The nominal classes are marked exclusively by prefixes . The classes of nouns and associated attributes as well as of subject and predicate must match in the construction of a sentence ( concordance ), but the prefixes of a class can be different for nouns, numerals, pronouns and verbs. In most Bantu languages, the classes - and the prefixes marking them - form the singular or plural of a word in pairs (see below the examples from the languages Ganda and Swahili).

Examples of nominal classes

Examples of nominal classes in the Ganda language :

- to the root ganda :

- mu-ganda "a Ganda"

- ba-ganda "the Ganda people" (plural of the mu class)

- bu-ganda "the land of the Ganda"

- lu-ganda "the language of the Ganda"

- ki-ganda "cultural things of Ganda" (e.g. songs)

- to the root -ntu :

- mu-ntu "human"

- ba-ntu "people"

- ka-ntu "little thing"

- gu-ntu "giant"

- ga-ntu "giant"

The hyphens between the prefix and the stem, which are used throughout this article for clarity, are not used in normal letters.

Examples from Swahili show the widespread doubling of the classes into a singular class and an associated plural class.

| Singular | German | Plural | German |

|---|---|---|---|

| m-do | person | wa-tu | People |

| m-toto | child | wa-toto | children |

| m-ji | city | mi-ji | Cities |

| ki-tu | thing | vi-tu | Things |

| ki-kapu | basket | vi-kapu | baskets |

| ji-cho | eye | macho | eyes |

| Ø-gari | automobile | ma-gari | cars |

| n-jia | Street | n-jia | Streets |

| u-so | face | ny-uso | Faces |

| ki-tanda | bed | vi-tanda | beds |

| u-fumbi | valley | ma-fumbi | Valleys |

| pa-hali | space | pa-hali | Places |

Adjectives and concordance in the noun phrase

There are relatively few real adjective roots in the Bantu languages, obviously a legacy of the original language. Most adjectives are derived from verbs . In many cases, relative constructions are used , e.g. B. “the man who is strong (from the verb to be strong )” instead of “the strong man”. The attributive adjectives follow their head noun, the noun prefix of the noun class of the noun is put in front of the adjective, so the class concordance applies . Examples from Swahili:

- m-tu m-kubwa "big person" ( m-tu "human", kubwa "big")

- wa-tu wa-kubwa "big people" (the wa class is the plural of the m class)

- ki-kapu ki-kubwa "large basket" ( ki-kapu "basket")

- vi-kapu vi-kubwa "large baskets" (the vi- class is the plural of the ki class)

All parts of a noun phrase, i.e. in addition to the noun also possessive pronouns, adjectives, demonstrative pronouns and numerals, are subject to class concordance (except for a few numerals that have been adopted from foreign languages, see below). Here are a few examples:

- wa-tu wa-zuri wa-wili wa-le "People (-tu) good (-zuri) two (-wili) those (-le) ", "those good two people"

- ki-kapu ki-dogo ki-le "basket (ki-kapu) small (-dogo) that (-le) ", "that small basket"

- vi-kapu vi-dogo vi-tatu vi-le "baskets (vi-kapu) small (-dogo) three (-tatu) those (-le) ", "those three small baskets".

Concordance of subject and predicate

The class of the subject must be taken up congruently by the predicate of a sentence, so there is also a concordance here . The following examples from Swahili show the principle (details on verbal construction see below):

-

ki-kapu ki-kubwa ki-me-fika "the big basket has arrived" ( ki-kapu "basket", -fika "arrive", -me- perfect marker)

Note: same class prefixes ki- for nouns and verbs, so-called alliteration -

m-toto m-kubwa a-me-fika “the big child (m-toto) has arrived”

Note: verbal a- prefix corresponds to the nominal m- class; thus different prefix morphemes for the same class - wa-tu wa-zuri wa-wili wa-le wa-me-anguka "those (wa-le) two (wa-wili) good (wa-zuri) people fell down (-anguka) "

-

wa-geni wa-zungu w-engi wa-li-fika Kenya

- lit. "Foreign (wa-geni) European (wa-zungu) many ( w-engi <* wa-ingi ) arrived ( -li- past marker ) in Kenya"

- "Many Europeans arrived in Kenya"

Possessive construction

Possessive constructions of the type "the man's house" (house = possession; man = owner, in German genitive attribute ) usually have the following form in the Bantu languages:

- Possession + [adjective attribute of possession] + (class marker of possession + a ) + owner

The connection of the class marker ( prefix of the nominal class ) with the suffixed -a often leads to contractions and other phonetic changes in the link.

Examples from Swahili:

- wa-tu wa (<* wa-a ) Tanzania "the people of Tanzania"

- ki-tabu cha (<* ki-a ) m-toto "the child's book (kitabu) "

- vi-tabu vya (<* vi-a ) wa-toto "children's books"

- ny-umba ya (<* ny-a ) m-tu "the house (nyumba) of the man"

- ny-umba n-dogo ya m-tu "the man's little (-dogo) house"

Class and importance

Although the class affiliation of nouns in today's Bantu languages is very difficult to determine semantically (see examples above), a list of the fields of meaning of the individual nominal classes was drawn up in many research papers on this topic . Hendrikse and Poulos (1992), cited here from Nurse (2003), provide a summary of these results. In addition to the reconstructed Protobantu class prefixes (after Meeussen 1967), the Ganda prefixes are listed as an example , here extended by the vocal prefixes, the so-called augments . As you can see, the Ganda prefixes largely correspond to the reconstructed Protobantu prefixes. For this purpose, some characteristic example words from the Ganda language are given. The last column describes the meaning fields of the individual classes.

| class | Proto-Bantu prefix | Ganda prefix | Ganda example | Meaning of the example | Meaning field of the class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mu- | o.mu- | o.mu-ntu | human | human beings, personifications, kinship terms |

| 2 | ba- | a.ba- | a.ba-ntu | People | Class 1 plural |

| 3 | mu- | o.mu- | o.mu-ti | tree | Natural phenomena, body parts, plants, animals |

| 4th | mini | e.mi- | e.mi-ti | Trees | Class 3 plural |

| 5 | (l) i- | li- / e.ri | ej-jinja | stone | Natural phenomena, animals, body parts, pairs, undesirable people, derogatives |

| 6th | ma- | a.ma- | a.ma-yinya | Stones | Plural of grades 5 and 14 ; Bulky terms, liquids, times |

| 7th | ki- | e.ki- | e.ki-cimbe | House | Body parts, tools, insects; Diseases and a. |

| 8th | bi- | e.bi- | e.bi-zimde | Houses | Class 7 plural |

| 9 | n- | en- | en-jovu | elephant | Animals; also people, body parts, tools |

| 10 | (li-) n- | zi- | zi-jovu | Elephants | Classes 9 and 11 plural |

| 11 | lu- | o.lu- | o.lu-tindo | bridge | long, thin things, elongated body parts; Languages, natural phenomena, etc. a. |

| 12 | tu- | o.tu- | o.tu-zzi | many drops | Plural classes 13 and 19 |

| 13 | ka- | a.ka- | a.ka-zzi | a drop | Diminutiva, derogativa; but also augmentatives |

| 14th | bu- | o.bu- | o.bu-mwa | Mouths | Abstracts, properties, collectives |

| 15th | ku- | o.ku- | o.ku-genda | going | Infinitives; some parts of the body, e.g. B. Arm , leg |

| 16 | pa- | a.wa- | . | . | Place names: Ankreis |

| 17th | ku- | o.ku- | . | . | Place names: radius |

| 18th | mu- | o.mu- | . | . | Place names: Inkreis |

| 19th | pi- | . | . | . | Diminutive (sg.) |

| 20th | ɣu- | o.gu- | o.gu-ntu | giant | Derogativa (sg.); also Augmentiva |

| 21st | ɣi - | . | . | . | Augmentiva, Derogativa |

| 22nd | ɣa - | a.ga- | a.ga-ntu | Giants | Class 20 plural |

| 23 | i- | e- | . | . | Place names; old infinitive class |

A look at this table shows that the meaning fields of the individual classes overlap, e.g. B. Animals can be assigned to classes 3-4, 5-6, 7-8, 9-10 and others. This means that it is almost impossible to predict which class a noun of a certain meaning category belongs to. The personal names, which are almost always assigned to classes 1 and 2, are an exception.

Pronouns

In addition to the dependent personal classics for pronomial subject and object , which are used in verb constructions (see there), there are also independent personal pronouns in the Bantu languages . They are used for special emphasis (emphasis) on the person, usually only as a subject. The possessive pronouns are not enclitic , but are placed after the noun to be determined with class concordance (see above) as an independent word. The two pronouns in Swahili are:

| person | staff | German | Possessive | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | mimi | I | -angu | my |

| 2.sg. | wewe | you | -ako | your |

| 3.sg. | yeye | he she | -ake | his / her |

| 1.pl. | sisi | we | -etu | our |

| 2.pl. | ninyi | her | -enu | your |

| 3.pl. | wao | she | -ao | her |

Some examples of the possessive pronoun:

- vi-tabu vy-angu (<* vi-angu) "my books"

- ki-tabu ki-le ni ch-angu (<* ki-angu) "that book is mine"

- ny-umba y-etu "our house"

- wa-toto w-angu w-ema "my good (-ema) children (-toto) "

In Protobantu, the demonstratives offer a differentiated three- or even four-level system of proximity and distance of reference (while e.g. in German there is only a two-level system with "this" and "that"):

- Level 1: Reference the immediate vicinity of the speaker: this one

- Level 2: Reference to the relative close range of the speaker: this

- Level 3: Reference to the immediate area of the addressee: those in the vicinity

- Level 4: Reference to third parties far away from the interlocutors: those back there, in the distance

For example, in the Venda (S20) language, all four levels have been preserved. Through a sound connection with the class markers, the demonstratives develop a special shape for each class. In the Venda, they are in classes 1 and 2 (person classes, simplified phonetics):

| class | step 1 | Level 2 | level 3 | Level 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ula | uyu | uyo | U.N |

| 2 | bala | aba | abo | bano |

However, only two levels of this have survived in many Bantu languages, e.g. B. in Swahili class marker + le “that”, hV + class marker “this” (“V” vowel in harmony with the class marker). As an exception, in the near demonstrative hV- the class marker is not used as a prefix but as a suffix. Here are a few examples from Swahili:

- ki-jiji hi-ki "this village (-jiji) "

- vi-jiji hi-vi "these villages"

- wa-toto ha-wa "these children"

- ki-jiji ki-le "that village"

- vi-jiji vi-le "those villages"

- wa-toto wa-le "those children"

While possessive and demonstrative pronouns are subject to class concordance (see above), the question pronoun in the Bantu languages only differentiates between the categories “person” and “thing”, e.g. B. in Swahili nani “who?”, Nini “what?”.

Numerals

The numerals for 1–5 and 10 come from Urbantu in many Bantu languages and are still relatively similar, for 6–9 they are of different origins (Arabic, European languages, African non-Bantu languages) and vary greatly in the individual languages. In Swahili they are:

| number | Swahili |

|---|---|

| 1 | -moja |

| 2 | -mbili / -wili |

| 3 | -tatu |

| 4th | - no |

| 5 | -tano |

| 6th | sita |

| 7th | saba |

| 8th | -nane |

| 9 | tisa |

| 10 | kumi |

| 11 | kumi na -moja |

| 12 | kumi na -vili |

The numerals for 1-5 and 8 are treated like adjectives and take part in the class correspondence (see above). The numerals for 6, 7 and 9 (italic) come from Arabic and are not subject to concordance, so they do not receive any class prefixes (see above). The tens (except “10”) and hundreds are also of Arabic origin.

Examples from Swahili:

- vi-su vi-tatu "three knives" ( concordance vi class )

- vi-su saba "seven knives" (no concordance)

- wa-toto wa-nne "four children"

- wa-toto kumi na m-moja "eleven children"

Verbal morphology

Verbal derivatives, aspect and tense

Verbal derivatives

With various suffixes on the verbal stem , derived verbs ( derivatives ) can be formed, of which most Bantu languages make extensive use. Some of the derivative endings have developed from proto-linguistic predecessors. Here are two examples:

The proto-linguistic reciprocal marker ( reciprocal = reciprocal ) "-ana" has been preserved in many Bantu languages, e . B.

- Swahili: pend-ana "love one another"

- Lingala : ling-ana "love one another"

- Zulu : bon-ana "see each other"

- Ganda : yombag-ana "fight with each other"

The causative marker “-Vsha” appears as -Vsha in Swahili, -ithia in Gikuyu, -isa in Zulu, -Vtsa in Shona, -Vsa in Sotho and -isa in Lingala. ("V" here stands for any vowel.)

The following table gives an overview of the derivation suffixes with some examples (based on Möhlig 1980).

| shape | meaning | function | example |

|---|---|---|---|

| -ana | reciprocal | Reciprocity of action | Swahili: pend-ana "love one another" |

| -Vsha | causative | Causing an action | Swahili: fung-isha "let bind" |

| -ama | positional | take a position | Herero: hend-ama "stand at an angle" |

| -ata | contactive | bring something into contact with each other | Swahili: kama "press"> kam-ata "summarize" |

| -ula / -ura | reversible | opposite act | Gikuyu: hinga "open"> hung-ura "close" |

| -wa | passive | Passivation of the action | Swahili: piga "to hit"> pig-wa "to be hit" |

Aspect, mode and tense

Aspects and modes are marked by suffixes , most Bantu languages have seven aspects or modes: infinitive , indicative , imperative , subjunctive , perfect , continuative and subjunctive . (In Bantuistics one usually speaks only of "aspects".)

Tenses are identified by prefixes that are inserted between the class prefix (see above) and stem (concrete examples in the next section). (In African literature, the tense prefixes are often incorrectly referred to as “tense infixes”.) The tenses and their marking prefixes vary greatly in the individual Bantu languages, so that they hardly developed from common proto-linguistic morphemes, but only later in the individual branches of the Bantu languages emerged more or less independently of one another.

Verbal construction in Swahili

Some of the Swahili verbal constructions are shown below.

infinitive

Infinitives are formed as ku + stem + end vowel ; the final vowel is -a if it is an original Bantu verb, -e / -i / -u if a foreign verb originating from Arabic is present. Examples:

- ku-fany-a "do, do"

- ku-fikr-i "think"

imperative

The imperative is expressed in the singular by the stem + final vowel , in the plural by adding -eni to the stem.

- som-a "lies!"

- som-eni "read!"

indicative

Finite verbal forms of the indicative have the shape

- Subject marker + tense prefix + object marker + stem

Subject marker is the class prefix (see above) of the nominal subject, but special subject markers are used for subjects of the person classes m- / wa- (nominal and pronominal). The same applies to the object markers, which can refer to a direct or indirect object. Subject and object markers of the person classes are compiled in the following table.

| person | subject | object |

|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | ni- | -n- |

| 2.sg. | u- | -k- |

| 3.sg. | a- | -m- |

| 1.pl. | tu- | -tu- |

| 2.pl. | m- | -wa- |

| 3.pl. | wa- | -wa- |

In all other classes, subject and object markers are identical and correspond to the respective class markers, e.g. B. ki- “es”, vi- “they (pl.)” In the ki- / vi class. The following table summarizes the Swahili tense prefixes .

| Tense | prefix |

|---|---|

| Present | -n / A- |

| past | -li- |

| Future tense | -ta- |

| Perfect | -me- |

| Conditional | -k- |

| Habitual | -hu- |

| Narrative | -ka- |

Some construction examples for the indicative

- a-li-ni-pa SUBJ - TEMP - OBJ - STEM "he (m-class) - VERG - me (m-class) - give"> "he gave (it) to me"

- ni-li-ki-nunua SUBJ - TEMP - OBJ - STEM "I - VERG - something (ki class) - buy"> "I bought something (that belongs to the ki class)"

- ni-li-m-sikia "I heard him" ( -sikia hear)

- a-li-ni-sikia "he heard me"

- ni-na-soma "I'm reading (currently)" ( -na- present tense prefix, -soma "reading")

- ni-ta-soma "I'll read" ( -ta- future tense prefix)

- ki-me-fika "it has arrived" ( -me- perkekt prefix, -fika arrive, ki- subject ki class)

- ni-ki-kaa "when I wait" ( -ki- conditionalis, -kaa "wait")

Benefactive

To make it clear that the action is being done to the benefit of a person, a so-called beneficial suffix -i- or -e- is inserted after the verb stem (but before the final vowel -a ) in addition to the object marker . Example:

-

a-li-ni-andik-ia barua

- Analysis: SUBJ (er) - TEMP (Verg.) - OBJ (me) - STAMM ( andik "write") - BENEFAK - ENDVOKAL + OBJ ( barua "letter")

- "He wrote me a letter"

Relative construction

Relative constructions of the form “the child who read a book” are expressed in Swahili by the relative prefix -ye- , which follows the tense prefix . Examples:

- m-toto a-li-ye-soma kitabu "the child who read a book"

- ni-na-ye-ki-soma kitabu "I who (I) am reading the book"

passive

In transitive verbs, the passive is indicated by inserting -w- or -uliw- in front of the infinitive ending vowel (usually -a ). Examples:

- ku-som-a "read"> ku-som-wa "to be read"

- ku-ju-a "to know"> ku-ju-liw-a (<* ku-ju-uliw-a ) "to be known"

Causative

Causatives are formed by adding the suffix -sha to the stem. Example:

- ku-telem-ka "go down"> ku-telem-sha "humiliate".

The examples are partly taken from Campbell (1995).

Comments on writing and literature

No Bantu language has developed its own script. Only Swahili had already adopted the Arabic script in pre-colonial times - perhaps since the 10th century - to fix a predominantly Islamic- religious literature. In addition to theological explanations, there were also legal texts, chronicles , geographicals , fairy tales , songs and epics . These epics (e.g. “The Secret of Secrets”, the “Herkal Epic”) are based on Arab models in terms of content and form, but they also show influences from East African Bantu culture. The importance of the Arabicized Swahili literature can be compared with that of the literatures in the Hausa , Ful , Kanuri and Berber languages , which were also written in Arabic at an early stage (in the 10th – 14th centuries). Since the late 19th century, Swahili, like all other written Bantu languages, was written in the Latin script .

Even without writing, the Bantu peoples possessed and still have a rich oral literature that includes myths , fairy tales , fables , proverbs , songs, and tribal stories . Under European - especially missionary - influence, the Latin alphabet was introduced in the middle of the 19th century, especially for the larger Bantu languages (mostly with minor language-specific modifications), and Bible translations were often the first written texts in a language. Since this time, missionaries, administrative officials and linguists have also been busy collecting sacred and profane songs, sayings and riddle poems, myths, fairy tales, sagas and epics of the Bantu peoples and recorded in the original languages. As a rule, only translations of these are known in Europe.

In the meantime, a rather extensive and varied new black African literature has developed, but most modern authors prefer one of the colonial languages as the vehicle for their works, as it allows them to reach a much larger target group. Oral Bantula literature plays an important role in terms of content and form as the basis for large areas of Neo-African literature.

The division of the Bantu languages into Guthrie zones

Malcolm Guthrie divided the Bantu languages into 16 groups ("zones") in 1948, which he designated with the letters A - S (without I, O, Q), for example Zone A = Bantu languages from Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. Within each zone the languages are grouped in units of ten, for example A10 = Lundu-Balong group and A20 = Duala group. The individual languages are numbered in each group of ten; for example A11 = Londo and A15 = Mbo. Dialects are indicated by small letters, e.g. B. A15a = Northeast Mbo.

Guthrie's system is primarily geographically oriented; based on current knowledge, it hardly has any genetic significance. However, it is still generally used as a reference system for the Bantu languages.

In the following, the individual zones are listed with their groups of ten and the languages with at least 100,000 speakers within the groups of ten are specified. The individual numbering of the languages is dispensed with, as it varies depending on the author. Details about these languages can be found in Ethnologue , which is also the main source for speaker numbers. Zones A, B and C are classified as Northwest Bantu , the rest as Central-South Bantu . Languages with at least 1 million speakers are shown in bold. As a rule, the number of native speakers is given as S1, S2 is the number of speakers including second speakers (only given if it differs significantly from S1).

Northwest Bantu

- Zone A - Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea - 53 languages with 5.1 million speakers

- Zone B - Gabon, Congo, Congo-Brazzaville - 40 languages with 1.6 million speakers

-

Zone C - Central African Republic, Congo, Congo-Brazzaville - 69 languages with 6.2 million speakers

- C10 Ngando

- C20 Ngundi

- C30 Mbosi: Mbosi (110 th.)

- C40 Lingala-Ntomba : Lingala (2 million, S2 9 million), Budza (250 thousand); Ntomba (100 thousand); Bangi (110 thousand), Bolia (100 thousand)

- C50 Ngombe: Ngombe (200 thousand), Bwa (Libua) (200 thousand)

- C60 Kele: Kele (200k)

- C70 Mongo : Mongo-Nkundu (400 thousand), Ngando (220 thousand)

- C80 Tetela: Tetela (750 thousand), Kela (200 thousand)

- C90 Bushong: Bushong (160k)

Central-South Bantu

-

Zone D - Congo, Uganda, Tanzania - 36 languages with 2.3 million speakers

- D10 Enya: Mbole (100k), Lengola (100k)

- D20 Lega-Kalanga: Lega-Shabunda (400 thousand), Zimba (120 thousand)

- D30 Bira-Huku: Komo (400 thousand), Budu (200 thousand), Bera (120 thousand)

- D40 Nyanga: Nyanga (150 thousand)

- D50 Bembe: Bembe (250 thousand)

-

Zone E - Kenya, Tanzania - 36 languages with 16 million speakers

- E10 Kuria: Gusii (Kisii) (2 million), Kuria (350 thousand); Suba (160 th.)

- E20 Kikuyu-Meru: Gikuyu (Kikuyu) (5.5 million), Kamba (2.5 million), Embu- Mbere (450 thousand); Meru (1.3 million), Tharaka (120 thousand)

- E30 Chagga: Chagga (400 thousand), Machame (300 thousand), Vunjo (300 thousand), Mochi (600 thousand), Rwa (100 thousand)

- E40 Nyika: Nyika (Giryama) (650 thousand), Digo (300 thousand), Duruma (250 thousand), Chonyi (120 thousand); Taita (200k)

- Zone F - Tanzania - 16 languages with 7 million speakers

-

Zone G - Tanzania, Comoros - 32 languages with 82 million speakers

- G10 Gogo: Gogo (1.3 million), Kagulu (200 thousand)

- G20 Shambala: Shambala (700 thousand), Asu (500 thousand)

- G30 Zigula-Zalamo: Luguru (Ruguru) (700 thousand), Zigula (350 thousand), Ngulu (130 thousand), Kwere (100 thousand)

- G40 Swahili: Swahili (Swahili, Kiswahili, Kiswahili) (2 million, S2 80 million), Comorian (650 thousand)

- G50 Pogoro: Pogoro (200k)

- G60 Bena-Kinga: Hehe (Hehet) (750 thousand), Bena (700 thousand), Pangwa (100 thousand), Kinga (140 thousand)

-

Zone H - Congo, Congo-Brazzaville, Angola - 22 languages with 12.5 million speakers

- H10 Congo: Congo (Kikongo) (1.5 million), Yombe (1 million), Suundi (120 thousand); Kituba (Munuktuba) (5.4 million, S2 6.2 million) Creole language

- H20 Mbundu: Luanda Mbundu (Kimbundu, Loanda) (3 million)

- H30 Yaka: Kiyaka (1 million), probe (100 thousand)

- H40 Hungana

-

Zone J - Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Congo, Rwanda, Burundi - 45 languages with 35 million speakers

- J10 Nyoro-Ganda: Ganda (Luganda) (3 million, S2 4 million), Chiga (1.5 million), Nyankore (Nkole) (1.7 million), Soga (Lusoga) (1.4 million .),

Nyoro (500,000), Tooro (500,000), Kenyi (400,000), Gwere (300,000), Hema (130,000) - J20 Haya-Jita: Haya (OluHaya, Ziba) (1.2 million), Nyambo (440 thousand), Jita (200 thousand), Zinza (150 thousand), Kara (100 thousand),

Kerebe (100 thousand) Th.), Kwaya (100 th.), Talinga-Bwisi (100 th.) - J30 Luyia: Luyia (3.6 million), Bukusu (650 thousand), Idhako-Isukha-Tiriki (300 thousand), Logooli (200 thousand), Nyore (120 thousand);

Masaba (750 thousand), Nyole (250 thousand) - J40 Nandi-Konzo: Nandi (1 million), Konzo (350 thousand)

- J50 Shi-Havu: Shi (650 thousand), Havu (500 thousand), Fuliiru (300 thousand), dogs (200 thousand), Tembo (150 thousand)

- J60 Rwanda-Rundi: Rwanda (Kinyarwanda) (7.5 million), Rundi (Kirundi) (5 million), Ha (1 million), Hangaza (150 thousand), Shubi (150 thousand)

- J10 Nyoro-Ganda: Ganda (Luganda) (3 million, S2 4 million), Chiga (1.5 million), Nyankore (Nkole) (1.7 million), Soga (Lusoga) (1.4 million .),

-

Zone K - Angola, Zambia, Congo, Namibia - 27 languages with 4.6 million speakers

- K10 Holu: Phende (450k)

- K20 Chokwe: Chokwe (1 million), Luvale (700 thousand), Luchazi (200 Tasd), Mbunda (250 thousand), Nyemba (250 thousand), Mbewela (220 thousand)

- K30 Salampasu-Lunda: Lunda (Chilunda) (400 thousand), Ruund (250 thousand)

- K40 Kwangwa: Luyana (110 th.)

- K50 Subia

- K60 Mbala: Mbala (Rumbala) (200 thousand)

- K70 Diriku

-

Zone L - Congo, Zambia - 14 languages with 10.6 million speakers

- L10 Bwile

- L20 Songye : Songe (1 million), Bangubangu (170 thousand), Binji (170 thousand)

- L30 Luba: Luba-Kasai (Chiluba, West-Luba, Luba-Lulua, Luva) (6.5 million), Luba-Katanga (Kiluba, Luba-Shaba) (1.5 million),

Sanga (450 thousand. ), Kanyok (200 thousand), Hemba (180 thousand) - L40 Kaonde: Kaonde (300k)

- L50 Nkoya

-

Zone M - Tanzania, Congo, Zambia - 19 languages with 9 million speakers

- M10 Fipa-Mambwe

- M20 Nyika-Safwa: Nyiha (Nyika) (650 thousand), Nyamwanga (250 thousand), Ndali (220 thousand), Safwa (200 thousand)

- M30 Nyakyusa-Ngonde: Nyakyusa-Ngonde (1 million)

- M40 Bemba: Bemba (ChiBemba, IchiBemba, Wemba) (3.6 million), Taabwa (300 thousand), Aushi (100 thousand)

- M50 Bisa-Lamba: Lala-Bisa (400 thousand), Seba (170 thousand); Lamba (200k)

- M60 Tonga-Lenje: Tonga (ChiTonga) (1.5 million), Lenje (170 thousand)

- Zone N - Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique - 13 languages with 13.8 million speakers

-

Zone P - Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique - 23 languages with 12.6 million speakers

- P10 Matumbi: Ngindo (220 thousand), Rufiji (200 thousand), Ndengerenko (110 thousand), Ndendeule (100 thousand)

- P20 Yao: Yao (2 million), Makonde (1.4 million), Mwera (500 thousand)

- P30 Makua: Makhuwa (Makua, EMakua) (5 million), Lomwe (Ngulu) (1.5 million), Chuwabo (600 thousand), Kokola (200 thousand),

Takwane (150 thousand), Lolo ( 150k), Manyawa (150k)

- Zone R - Angola, Namibia, Botswana - 12 languages with 5.8 million speakers

-

Zone S - Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Botswana, Namibia, South Africa - 26 languages with 58 million speakers

- S10 Shona: Shona (ChiShona) (11 million) (including Manyika (1 million) and Kalanga (850 thousand)),

Ndau (700 thousand), Tewe (250 thousand), Nambya (100 thousand) - S20 Venda: Venda (ChiVenda) (1 million)

- S30 Sotho-Tswana : Sotho (South Sotho, Sesotho) (5 million), Pedi (North Sotho, Sepedi, Transvaal-Sotho) (4 million),

South Ndebele (600 thousand); Tswana (Setswana) (4 million); Lozi (600k) - S40 Nguni: Zulu (isiZulu) (10 million), Xhosa (isiXhosa) (7.5 million), North Ndebele (1.6 million), Swati (Siswati, Swazi) (1.7 million)

- S50 Tswa-Ronga: Tsonga (Xitsonga, Thonga, Shangaan) (3.3 million), Tswa (700 thousand), Ronga (700 thousand)

- S60 Chopi: Chopi (800 thousand), Gitonga-Inhambane (250 thousand)

- S10 Shona: Shona (ChiShona) (11 million) (including Manyika (1 million) and Kalanga (850 thousand)),

literature

Bantu languages

- Rev. FW Kolbe: A Language-Study based on Bantu. Trübner & Co., London 1888. Reprint 1972.

- Malcolm Guthrie: The Classification of the Bantu Languages. London 1948. Reprint 1967.

- Bernd Heine, H. Hoff and R. Vossen: Recent results on the territorial history of the Bantu. On the history of language and ethno-history in Africa. In: WJG Möhlig et al. (Ed.): New contributions to African research. Reimer, Berlin 1977.

- Derek Nurse and Gérard Philippson: The Bantu Languages. Routledge, London 2003.

- AP Hendrikse and G. Poulos: A Continuum Interpretation of the Bantu Noun Class System.

In: DF Gowlett: African Linguistic Contributions. Pretoria 1992. - AE Meeussen: Bantu Grammatical Reconstructions. Africana Linguistica 3: 80-122, 1967.

- Wilhelm JG Möhlig: The Bantu languages in the narrower sense.

In: Bernd Heine et al. (Ed.): The languages of Africa. Buske, Hamburg 1981. - David Phillipson: The Migrations of the Bantu Peoples.

In: Marion Kälke (ed.): The evolution of languages. Spectrum of Science, Heidelberg 2000. - J. Vansina: New Linguistic Evidence and 'The Bantu Expansion'. Journal of African History (JAH) 36, 1995.

- Benji Wald: Swahili and the Bantu Languages.

In: Bernard Comrie (Ed.): The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press 1990.

African languages

- George L. Campbell: Compendium of the World's Languages. Routledge, London 2000 (2nd edition)

- Joseph Greenberg: The Languages of Africa. Mouton, The Hague and Indiana University Center, Bloomington 1963

- Bernd Heine and others (ed.): The languages of Africa. Buske, Hamburg 1981

- Bernd Heine and Derek Nurse (eds.): African Languages. An Introduction. Cambridge University Press 2000

- John Iliffe : History of Africa , 2nd edition: CH Beck, Munich 2003 ISBN 3-406-46309-6

Lexicons

- AE Meeussen: Bantu Lexical Reconstructions. Tervuren, MRAC 1969, reprint 1980

- A. Coupez, Y. Bastin and E. Mumba: Bantu Lexical Reconstructions 2. 1998

- Nicholas Awde: Swahili - English / English - Swahili Dictionary. Hippocrene Books, New York 2000

Web links

-

Ernst Kausen, The classification of all Bantu languages within the Niger-Congo languages (DOC; 227 kB)

2007, updated classification of all Bantu languages according to Guthrie with speaker numbers from Ethnologue 2005. - List of Bantu Language Names with Synonyms ordered by Guthrie Number ( List of Bantu Language Names with Synonyms)

- Jacky Maniacky, Les langues bantoues - The Bantu Languages ( The Bantu languages , French and English version)

- Introduction to the Languages of South Africa (Introduction to the languages of South Africa)

- Journal of West African Languages (A journal for West African languages)

- Comparative Bantu OnLine Dictionary (CBOLD) (Comparative Bantu Internet Dictionary, English)