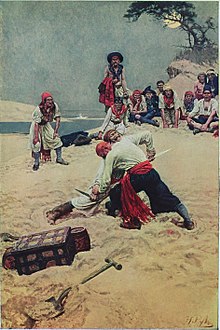

treasure

The treasure or treasure is after the legal definition of § 984 BGB a movable thing that was hidden for so long that, their owners can not be determined more.

General

The standard purpose of the lost property right is on the one hand to protect the property rights of the loser and on the other hand to enable the finder to acquire original property in the case of unknown losers and thus to clear up the property system. A treasure also has mystical features that set it apart from normal finds and make it valuable. This is expressed in Meyer's Large Konversations-Lexikon of 1909 , which describes the treasure as “in general something excellent, carefully preserved; then above all a thing that has been hidden for so long that the owner can no longer be identified ”.

Coin find

A coin find means old, recovered coins. Single or scattered finds are mostly lost coins, while bulk or depot finds (including treasure finds) are those that were deposited in the past for various reasons.

A find can only be used by archaeologists if the context of the find is known. A coin can hardly be used as a historical source without any context. Coin finds provide information about the distribution of coins, possibly via trade routes, and enable the chronological classification of objects that were associated with the coin find. Litter finds from Roman legionary camps prove z. B. the duration of the occupancy and, in some cases, the relocation of troops.

A coin find is a treasure within the meaning of Section 984 of the German Civil Code (BGB) and half becomes the property of the finder and half of the property or object in which the coin was found (in some federal states there is a tax obligation). It must be reported and made available for academic processing.

Legal bases

The legislature therefore saw a need for regulation for all items lost to the original owner, for which the owner can no longer be determined due to their long hidden storage. This is the core of the legal definition of § 984 BGB , which at the same time requires that a treasure must be discovered and, as a result of its discovery, must be taken possession of by the finder. The legislature has contented itself with this one provision for the treasure trove.

content

While the owner of the lost property is known or can be determined in a normal find, this is not the case with a treasure find. A (movable) thing is hidden if it is not immediately perceptible to the senses . If the owner remains to be identified, it is not a treasure, but a find. This finding is without possessions , the treasure is in addition also abandoned . In contrast to finding, discovery is decisive with treasure, but not taking possession. The finder discovers the thing by perceiving it and taking it for himself. What needs to be clarified is what is meant by “hidden”. Objects lying open are not hidden if the circumstances make it much more difficult to find them. Hidden storage eludes human perception through the sense organs. The discovery leads the long-hidden object back to human use, for example through an exhibition in a museum. Discovering is a real act that does not require legal competence. In contrast to a normal find, the discovery of a treasure is rewarded, because with the discovery, the discoverer and property owner acquire a real entitlement to the treasure. The acquisition of property then occurs through occupation.

The question still remains, who is considered to be the discoverer of a treasure? During demolition work in 1984 a shovel truck driver came across 23,200 gold and silver coins from the Middle Ages while demolishing a foundation. According to the judgment of the BGH , the shovel truck driver and the state of Schleswig-Holstein were entitled to half of the joint ownership, because the shovel truck driver's employer had not consciously sought the treasure through his employee - it was a chance find. The employer is only considered a discoverer if he has specifically given his employees the task of treasure hunt .

Legal consequences

In general, two potential owners of a treasure find come into question, namely the property owner of the property on which the treasure was found (principle of accession) or the finder (principle of occupation). Emperor Hadrian found a compromise that gave each of the two half ( Hadrian's division ).

The legal reality follows the Sachsenspiegel : Treasure finds above the plowing depth remain with the finders, usually with the (tacit) consent of the landowner. Almost only official archaeologists dig deeper than 30 cm. According to the Saxon mirror, everything below the plowing depth belonged to the king.

Paragraph 984 of the German Civil Code (BGB) takes up the Roman compromise for treasure finds, because the finder and the property owner each acquire half of the treasure; this is joint (§ § 752 f. BGB) co-ownership ( § 1008 f. BGB). If the finder conceals the found thing, he commits embezzlement from the property owner ( § 246 StGB). Few treasure hunters are punished for embezzlement.

In all federal states except Bavaria, civil property rights are overlaid by public monument protection law . The state law partly as a control - the so-called treasure trove - which immediately allocates the ownership of the treasure the state, often called uncompensated expropriation . The requirement that the treasure find is reported is not often met.

Public law restrictions

Most federal states have passed monument protection laws that make digging for ground monuments dependent on official approval. A treasure find is then subject to an obligation to notify the competent authority. According to the opening clause of Art. 3 , Art. 73 EGBGB , even a treasure shelf is permissible, according to which a treasure, when found, goes directly to the state as the new owner. With the help of Art. 73 EGBGB, the states can determine that culturally, historically or scientifically significant finds fall into the property of the state when they are discovered.

The provision does not affect a legal status that existed when the BGB came into force, but does not allow further development of this right, for example to include fossil finds . Art. 1, Para. 2 EGBGB allows for new state law provisions, but only with regard to the legal matter which - here in Art. 73 EGBGB - has been listed as remaining unaffected. Accordingly, the state legislature - including that of a country in which no treasure shelf existed at the time the BGB came into force - may continue to issue state law regulations on regalia and also change their content; however, the subject of its regulations is limited by the limits of the traditional shelf concept. Fossils - the fossilized remains of prehistoric animals and plants - have never been owned by anyone. Art. 73 in conjunction with Art. 1 (2) EGBGB can therefore not be used to establish the legislative power of the state legislature for regulations on fossils. The responsibility of the states for the protection of monuments results from Article 70.1 of the Basic Law.

Because of the treasure shelf, the practical significance of § 984 BGB is small. After North Rhine-Westphalia tightened the monument protection regulations in July 2013 and now directly grants the state ownership of treasure finds, Bavaria is the only federal state without this regulation.

Treasure hunt

International

Treasures are valuable things that have been hidden, buried or sunk for a long time and whose existence has not been clarified. In the case of many treasures, the ownership structure is lost in the dark of history. Improved location processes and new recovery techniques have made it possible to recover previously undiscovered treasures, especially at sea. Professional treasure hunters work systematically to locate and recover such treasures.

For archeology, treasure hunters pose an enormous problem, as they are usually interested in the material value and destroy the securing of evidence at the place of discovery. Treasure hunters thus destroy historical knowledge to a high degree.

Several states are usually involved (country of the salvage company, country of the sunken ship and possibly the state to which the salvage area belongs), so that conflicting legal systems can arise. Maritime law and international private law apply to finds on the high seas . In the law of the sea there is a “doctrine of state immunity”, according to which the wrecks of ships in service on non-commercial voyages remain the property of the countries that commissioned them. Private international law becomes applicable when there is treasure outside the 12-mile zone from a coast. A UNESCO agreement also stipulates that shipwrecks belong to the ship's country of origin, regardless of where they were found.

Switzerland

A treasure belongs to the property owner, the finder has a contractual right to appropriate remuneration up to half of the value (Art 723 Paragraphs 2 and 3 ZGB). If, on the other hand, abandoned natural bodies or antiquities of considerable scientific value are found, they become the property of the canton in whose territory they were found (Art. 724, Paragraph 1, Civil Code).

Austria

According to Section 399 of the Austrian Civil Code, Austria applies the same civil law regulation as Germany, but does not have the treasure shelf like Germany and Switzerland.

Fabulous treasures - fiction, literature, films (selection)

|

Treasure finds and treasures (selection)

See also

|

Web links

- On the misfortune of finding treasure , Frankfurter Allgemeine from April 25, 2011.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schatz in Meyer's Großes Konversations-Lexikon from 1909; on Zeno.org, accessed July 19, 2017.

- ↑ A movable thing that has been hidden for so long that its owner can no longer be determined.

- ↑ OLG Cologne, OLGZ 92, 253: Coins in cardboard box in the attic that is difficult to access

- ↑ a b c Hans Josef Wieling, Property Law , 2007, p. 160 ff.

- ↑ BGH, judgment of January 20, 1988 = NJW 1988, 1204: "Lübecker Schatzfund" ( Memento of the original of July 18, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Karl Zeuner, The buried treasure in the Sachsenspiegel , 35. Communications from the Institute for Austrian Historical Research 22, 1901 pp. 420–442.

- ↑ Arndt Koch, treasure hunt, archeology and criminal law - criminal aspects of the so-called "robbery graves" , in: Neue Juristische Wochenschrift (NJW) 2006 issue 9, pp. 556-560.

- ↑ BVerfG NJW 1988, 2593.

- ↑ BVerwG, judgment of November 21, 1996, Az .: 4 C 33/94.

- ↑ Norbert von Frankenstein (ed.), Treasure Hunt: Verschollene und Founde Schätze , 1993, p. 9 f.