Battle for Wroclaw

| date | January 23 to May 6, 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Wroclaw , Lower Silesia |

| output | Victory of the Soviet Union |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

|

6th Army 3rd Armored Guard Army total of 200,000 men |

269th Infantry Division Volkssturmbataillone other units (40,000 men in total) |

| losses | |

|

13,000 dead |

6,200 dead |

The Battle of Breslau describes the attempt by the German Wehrmacht to build a line of defense on the Oder , to prevent the important traffic junction of Breslau from being enclosed and to defend the " Fortress Breslau ". These activities began on January 23, 1945, when the Red Army created bridgeheads at Opole and Ohlau southeast of Breslau on the Oder. The actual battle for the city began on February 15th with the containment in the course of the Lower Silesian Operation and ended on May 6th with the surrender to the Soviet 6th Army .

The opponents

The Siege of Breslau was between the German middle army group under Ferdinand Schörner and the 1st Ukrainian Front of Ivan S. Konev held. The German 17th Army (led by Friedrich Schulz and later Wilhelm Hasse ) and the Soviet 3rd Armored Guard Army ( Pawel S. Rybalko ) and the Soviet 6th Army ( Wladimir A. Glusdowski ) faced each other. In the city of Wroclaw only part of the 269th Infantry Division was included, which was no longer a division , but only a battle group .

The city declared a fortress had a strong defense of at least 24,000 men. These were divided into the less powerful soldiers of the Volkssturm , specialists from the armaments factories and other military personnel from the National Socialist state organizations. The more powerful units included those of the Wehrmacht (for the most part vacationers from the front and soldiers from the replacement companies) and those of the Waffen SS .

Major General Hans von Ahlfen had authority in the so-called fortress of Breslau until March 7, 1945, and then General of the Infantry Hermann Niehoff until the surrender on May 6 . The political leader of the fortress was Gauleiter Karl Hanke , who had a high status of power and was in command of the Volkssturm troops stationed in Breslau.

The fortress city

The NSDAP's claim to leadership

By order of the Reich Defense Commissioner and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels , Hanke had activated National Socialist leadership as a political organ in all Wehrmacht units. The Nazi command officer (NSFO) van Bürck was responsible for the fortress command with special powers. The main task of this political department was above all to control the intelligence service for the Wehrmacht, to raise morale through propaganda agitation and to check the political sentiments of the soldiers.

evacuation

On January 20, Gauleiter Hanke called on the unfit for military service to leave the city that had been declared a fortress immediately. It was a cold, severe winter and Breslau was full of people, many of whom had come here in treks over the past few weeks from the villages and towns to the right of the Oder lowlands. Many from the rest of the western Reich had lived here since the last years of the war and had so far been spared from the bombing of enemy aircraft. All of them had to vacate the fortress city at short notice. However, no preparations were made to evacuate the city. Already on the first day there was panic in the train stations. The trains couldn't take the masses. Gauleiter Hanke therefore ordered women and children to march to the south-west of the surrounding area near Kostenblut (Kostomloty) and Kanth . Thousands of children and old people perished during the panic escape in frost and snow. Because of these events, many Wroclaw residents now refused to leave the city. Around 200,000 men and women who were not fit to fight, as well as young girls and Pimpfe of the Hitler Youth remained in the city.

The northern and eastern suburbs of Wroclaw were forcibly evacuated because the first Soviet onslaught was expected here. The Wehrmacht and Volkssturm took up residence in the abandoned houses for the next few days . Political power was incumbent on the party organs and their commander, the Gauleiter. With the evacuation order from the civilian population, Gauleiter Hanke had all offices and institutions that were not absolutely necessary for the defense of the fortress relocated to other areas of the empire . Many pupils and their teachers also left the city: the university , the university clinics, the technical center, the botanical institute and the museum facilities were relocated. The clergy were also asked to leave the city.

Reprisals

Men who could handle weapons had to stay. Fifteen-year-old Hitler Youth and sixty-year-old men were mobilized for the last Volkssturm contingent. The commanders threatened those who refused to submit to strict measures with arrest and other punishments, and in the event of cowardice in front of the enemy with death . The fortress commander was able to convene court martial in order to have alleged deserters , so-called defensive disruptors , saboteurs or spies executed . As a political organ, the Gauleiter could also invoke the martial law and have executions carried out.

The most prominent victim of these reprisals on the part of the National Socialist state is the Deputy Mayor Wolfgang Spielhagen . Spielhagen had advised surrender in order to prevent even more civilian casualties. On January 28th, he was shot dead by members of the Volkssturm on the Breslauer Ring , near the town hall . The Gauleiter gave the order for liquidation himself. The victim's body was then taken to the Oder and thrown into it. Gauleiter Hanke had it publicly announced: "Whoever fears death in honor, dies it in shame."

War propaganda

Fortress commander von Ahlfen issued the following order to discipline the troops on February 8th to his officers: “I make it the duty of all leaders to maintain the position entrusted to them. Anyone who gives up a position without authorization and goes back is sentenced to death by the court martial for cowardice. Every leader, regardless of which unit, has not only the right but also the duty to assert himself against shirkers who leave their position by all means, if necessary with the use of the weapon. ”In a court judgment published in February it says: “Two soldiers from a unit deployed in the fortress area had been sent back to the next village in the position to fetch blankets. Instead, in this village, they took off their uniforms, put on civilian clothes, and set out on foot to get home. On February 5th they were seized by a patrol of the Wehrmacht and sentenced to death by a court martial on the same day and shot. "

defense

An inner-city evacuation was carried out on February 10th. The residents of the eastern parts of the city between the Oder rivers and the urban areas in the west had to vacate their apartments and leave their fully packed suitcases behind.

Breslau was hardly fortified militarily. On February 15, Soviet troops besieged the suburbs of Wroclaw from the south and west. With flamethrowers and bazookas one fought almost to every house, and there was hardly a house that had not been badly damaged. A Moscow newspaper reported on the house- to-door fighting in Wroclaw: " The fighting was not just in every house, floor or room, but around every window where the Germans installed machine guns and other automatic weapons."

During their street attacks, the Soviet raiders first destroyed the corner buildings of the rows of houses with grenade launchers or tank bombardment . The flames then drove the defenders from the first houses, then the flamethrowers followed and set building after building on fire. To prevent the streets from being burned out, troops of the Wehrmacht, with the help of civilians, cleared the furniture, all combustible objects from the apartments, offices and shops onto the street and burned everything that was brought onto the street.

Buildings in the city were demolished in order to gain material for defensive systems and to take cover from the attacking enemy in urban warfare. Guns were deployed in the parks and promenades. The Wehrmacht blew up entire houses at intersections. On every street corner, on every advertising column , posters called for help and fight. Old men who were no longer strong enough to leave the city had to tear up the pavement and erect stone barricades. Barricades were built from the rubble. Trams came to barricade streets. Moving vehicles were brought in on horses and burned-out tanks were dragged in. Parterres and cellars turned into shooting ranges .

An armored train was successfully used in the defense of Wroclaw. The armament of this train consisted of four hulls for heavy tanks, which were equipped with four 8.8 cm anti -aircraft guns, one 3.7 anti-aircraft gun and four 2 cm anti-aircraft guns and two MG 42 guns. The train also had a radio station.

care

The ammunition supply, which soon became urgent, was carried out by air from Dresden . Supplies were also flown in via Königgrätz . The fighting of the last few weeks had run out of ammunition and supplies, so that the future defense was endangered without constant supplies by air. All available three-engine transport aircraft ( Ju 52 ) were in constant use. The planes landed at Gandau airfield in the west of the city. The besiegers soon controlled the air supply, so that due to flak and fighter pilot fire, approaches with transport aircraft could only be made at night. The city, on the other hand, was plentifully supplied with food and other supplies. The meat from around 16,000 pigs was stored in the cold stores. Before the siege, cattle had been herded into the city from the surrounding area, although they did not have any fodder in the fortress.

After the Soviet troops captured the airfield, General Niehoff ordered a second runway to be laid behind the Kaiserbrücke. He had demolition squads cut a lane 300 m wide and one kilometer long along Kaiserstrasse, for which the Luther Church was also blown up. Forced laborers and civilians had to work day and night in the constant fire of the besiegers. The provisional runway was not of military importance. It is reported that only one plane took off on it: that of Gauleiter Hanke, who pulled away just before the fall of the city.

Fate of the city

During the Easter holidays in 1945, on April 1st and 2nd, hundreds of planes dropped several thousand bombs on the urban area of Wroclaw. The most massive bombing took place on Easter Monday. The dropped phosphorus bombs caused serious fires across the city.

Of 30,000 buildings, 21,600 were in ruins at the end of the fighting. Many industrial plants and valuable cultural monuments were completely destroyed.

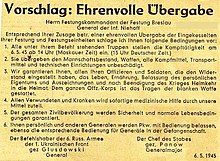

surrender

Breslau surrendered on May 6, 1945, four days after the last defenders of Berlin laid down their arms.

The surrender did not bring any relief for the remaining population, who had suffered for weeks from forced labor, sieges, fighting and destruction. Hospitals and sewers were destroyed, and epidemics spread in view of the catastrophic conditions. There were also looting, assaults and rape by Red Army soldiers .

According to estimates by the British historian Norman Davies , a total of 170,000 civilians, 6,200 German and 13,000 Soviet soldiers were killed in the battle for Breslau. 12,000 German and 33,000 Soviet soldiers were wounded. Other estimates put 20,000 civilians killed.

General Niehoff surrendered and spent ten years in Soviet captivity.

epilogue

The siege of the city of Breslau in 1945 met with great interest in post-war German historical research . Shortly after the end of the war, the siege of Breslau in the Federal Republic of Germany became the subject of numerous publications. For example, Friedrich Grieger (1894–1961) published a non-fiction book in 1948 under the title How Breslau fell (Metzingen: The Future, 1948), in which he made the German military and party leadership responsible for the senseless defense of the city. J. Kaps, J. Thorwald, H. Hartung, who published their works between 1952 and 1956, were far more cautious in expressing their opinions in this regard. Finally, in 1963, a book was published under the title So fought Breslau , which was written by Generals H. von Ahlfen and H. Niehoff, the last commanders of the city. Numerous articles and lively polemics about the usefulness of defending the city were published in West German magazines from the post-war period. Hugo Hartung , Werner Steinberg and Maria Langner provided the siege of the city with rich material for their works.

filming

- The Children of Escape - Documentary (2006)

literature

- Volker Ullrich : Eight days in May. The last week of the Third Reich. CH Beck, Munich 2020, ISBN 9783406749858 , pp. 183-188.

- Norman Davies , Roger Moorhouse: Breslau - the flower of Europe: The history of a central European city. Translation by Thomas Bertram. Droemer Verlag, 2005

- Horst GW Gleiss: Breslau Apocalypse 1945 - Documentary chronicle of the agony and downfall of a German city and fortress at the end of the Second World War . Ten volumes. Natura Et Patria, Rosenheim 1986–1997.

- Friedrich Grieger: How Breslau fell . The future, Metzingen 1948.

- Ernst Hornig : Breslau 1945 . Korn, Munich 1975.

- Ivan Stepanowitsch Konew : The year forty-five . German Military Publishing House , Berlin 1969, ISBN 3-327-00826-4 .

- Walter Laßmann: My experiences in the fortress of Breslau . Diary entries of a pastor. Edited and commented by Marek Zybura . Neisse Verlag, Dresden 2012.

- Ryszard Majewsky: The battle for Breslau . Union Verlag, Berlin 1979.

- Karol Jonca , Alfred Konieczny (eds.), Stanislaw Hubert (editor): Fortress Breslau: Documenta Obsidionis 16.02–06.05.1945 . (Introduction in Polish, German, English, Russian; all documents in German). Panstwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowo, Breslau 1962.

- Paul Peikert : Fortress Breslau . Union-Verlag, Berlin 1966.

- Paul Peikert, Karol Jonca, Alfred Konieczny (eds.): Fortress Breslau - in the reports of a pastor . Wrocław 1996.

- Jürgen Thorwald : It started on the Vistula . Steingräben-Verlag, Stuttgart 1959.

- Gregor Thum : The foreign city - Breslau after 1945 . Pantheon, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-570-55017-6 .

- Hans von Ahlfen : The struggle for Silesia . Motorbuch Verlag, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-87943-480-8 .

- Hans von Ahlfen, Hermann Niehoff : This is how Breslau fought - defense and fall of Silesia’s capital . Gräfe and Unzer , Munich 1963.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Photo of the Wroclaw armored train

- ^ Andreas R. Hofmann: The post-war period in Silesia. Böhlau, 2000. p. 18.