Pig farming in ancient times

The pig farming in ancient times is an important part of the history of pig farming and the ancient economic history . It was used almost exclusively for the production of pork . It was widespread to varying degrees throughout the Mediterranean and is already mentioned in Homer . By evaluating literary, epigraphic and archaeological evidence, a relatively precise picture of ancient pig breeding can be obtained. Its importance is shown, among other things, in the fact that personalities like Aristotle and Cato dealt with it and that the pig trade was promoted through tax breaks just a few years before the fall of the Western Roman Empire .

Greece

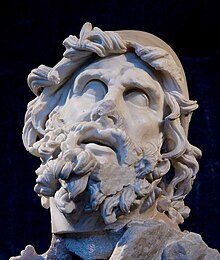

In contrast to cattle , which were mainly needed as work animals, and sheep , which were valued primarily for their wool , pigs in ancient Greece were used exclusively for meat production as early as Homer's time. The heroes of the great epics Iliad and Odyssey eat pork several times. The Odyssey also describes the keeping of pigs in detail, Homer's report is probably based on the keeping methods of his time: during the day the pigs graze outdoors and are looked after by swineherd; at night 50 sows are locked in a stable. A total of 600 sows and 360 boars are said to have been in the care of Eumaius , Odysseus ' swineherd . This number, which was quite high for the time, should underline the wealth of his master.

However , intensive pork consumption and pig farming have already been demonstrated in the Mycenaean period . It is clear from Linear B of -documents palace of Pylos dating from around 1200 BC. BC shows that in the empire of Pylos pigs were fattened in nine larger centers, the meat of which was probably intended primarily for banquets. At that time, however, pork was already being smoked or cured and thus made long-lasting. Statistical evaluations in Nichoria showed that the bones of pigs were mostly just as common as those of goats and sheep, which were also kept for the production of wool (or fur in goats) and milk.

Today's knowledge of pig farming in Classical and Hellenistic Greece is based primarily on the sparse literary evidence. The philosopher Aristotle wrote about pigs in his animal history . According to him, the fattening lasted 60 days, the animals were fed on barley , millet , figs and acorns during this time , but were only suitable for breeding when they were one year old. According to Plutarch , pigs have been in Athens since at least the 5th century BC Chr. Kept in large numbers, but also elsewhere poor women earned extra income by fattening piglets. A preserved red-figure vase shows pigs being driven to the market. Overall, however, the news about pig farming in ancient Greece is too rare and scattered to paint a more accurate picture.

Rome

distribution

Pig farming in the Roman Empire was mainly concentrated in central Italy and northern Gaul . Pork was particularly consumed in the cities, while its share of meat consumption by rural residents was significantly lower. The inhabitants of the city of Rome and its surroundings showed a particular fondness for pigs ; two thirds of all animal remains found there were pigs. Pig farming was also practiced in the Po Valley as early as the 2nd century BC. Widespread.

The Roman eating habits influenced those of the neighboring regions: While in Campania in the Republican times beef was mainly consumed, pork consumption approached that in Rome during the imperial period . In Hispania , the percentage of pigs eaten doubled after the Roman conquest. In Britain , Greece , Upper and Lower Germany , on the other hand, pig breeding did not experience a comparable upturn. She was never able to gain a foothold in Syria and Egypt . Those of the soldiers stationed there who came from regions that consume pork usually adapted to local preferences.

attitude

In addition to archaeological finds, the image that today's researchers have of pig farming in the Roman Empire is based primarily on the works of Roman agrarian writers. In addition to Cato, these were in particular the late Republican author Varro and Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella and Pliny the Elder , who wrote in the early imperial period . According to Varro and Columella, the pigs were kept in stalls called hara at night , where they could be separated. This was necessary because otherwise there was a risk that piglets would be crushed by older animals. Both authors also explicitly point out the importance of clean stables. During the day, the pigs grazed outside, preferably in oak forests , which were considered particularly cheap pastures. The pasture grounds should also give the animals the opportunity to wallow in the mud.

Varro recommended keeping pigs in flocks of around 100 sows and 10 boars, although he knew that some breeders kept more than 150 pigs. Unless they were intended for breeding, the boars were castrated at one year . Breeding animals were also castrated when they had fulfilled their task at the age of three to four. Boars suitable for breeding had to meet certain criteria. This included a stocky build with short legs and a protruding belly, a strong neck and a short trunk. If the breeding was successful, only the most promising young animals were raised, especially with large litters, the others were usually sold.

distribution

The maximum price edict of the first late antique emperor Diocletian (284–305) names prices for pork and for the transport of pigs, but unlike horses, cattle or goats, no prices for live animals. Diocletian's predecessor Aurelian (270–275) had pigs bought in southern Italy in order to supply the population of the city of Rome with meat during the winter months. The animals were either delivered directly by large landowners or were bought from local markets with funds collected from them. Every Roman eligible to receive government food donations received five pounds of meat for five months a year. In addition to pork, sheep and beef were also served.

Since the pigs intended for the imperial meat donations lost about 20 percent of their weight during the transport to Rome, the respective emperor provided 25,000 amphorae of wine, of which more pigs could be bought to compensate for the weight loss. In 452 the Western Roman army master Aëtius finally set the quantities and prices. Since then, the pig traders ( lat. Suarii ) had to pay a solidus for 240 Roman pounds (around 78.6 kg) of pork . The great importance that these pig dealers had is shown by the fact that the heads of this guild, privileged since Septimius Severus (193-211), were third-order comites from 419 and in 458 were the only professional group to be explicitly exempted from a general tax increase by Emperor Majorian . Since the reform of Aëtius, who, in addition to his military duties, was also the patron saint of the pig traders, they received 6400 solidi from Lucania , 5400 solidi from Samnium and 1950 solidi from Campania for the purchase of pigs . In total, more than 1000 tons of pork should be bought every year.

Ancient sources

- Aristotle , animal history (Greek Περὶ τα ζωα ιστοριαι) 545a; 573a-b, 595a.

- Athenaios , Banquet of the Scholars (Greek Δειπνοσοφισταί) 14,656 f.

- Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella , Twelve Books on Agriculture (Latin Rei rusticae libri duodecim ) 7: 9-11 ( online ).

- Homer , Iliad (Greek Ιλιάς) 9.208; 19,196 f .; 23.32.

- Homer, Odyssey (Greek Oδύσσεια) 8,474 ff .; 10.237-243; 10,388-397; 14.5-20; 14.26 ff .; 14.81; 14,410 ff .; 14,414-438; 15.555.

- Gaius Plinius Secundus Maior , Natural History (Latin Naturalis historia ) 8.205–213 ( online at LacusCurtius ).

- Plutarch , Moralia (Greek Ηθικά) 580e – f.

- Polybios , Historien (Greek Ιστορίαι) 2.15 ( online ).

- Marcus Terentius Varro , About Agriculture (Latin Rerum rusticarum de agri cultura ) 2,4 ( online ).

literature

- Alexander Demandt : The late antiquity. Roman history from Diocletian to Justinian 284–565 AD (= Handbook of Classical Studies . 3rd section, 6th part). 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55993-8 , p. 392, 400, 432 f., 436 f., 537 .

- Joan N. Frayn: The Roman Meat Trade . In: John Wilkins (Ed.): Food in Antiquity . University of Exeter Press, Exeter 1995, ISBN 0-85989-418-5 , pp. 107-114 .

- Helmut Meyer, Peter Robert Franke , Johann Schäffer: Domestic Pigs in Greco-Roman Antiquity. A morphological and cultural-historical study . Isensee, Oldenburg 2004, ISBN 3-89995-083-6 .

- Ferdinand Orth : Pig . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume II A, 1, Stuttgart 1921, Col. 801-815.

- Joris Peters: Roman animal husbandry and animal breeding. A synthesis of archaeozoological investigation and written and pictorial transmission (= Passauer Universitätsschriften zur Archäologie . Volume 5 ). Leidorf, Rahden / Westfalen 1998, ISBN 3-89646-172-9 , p. 107-134 (also habilitation thesis, University of Munich 1996).

- David S. Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay . Routledge, London / New York 2004, ISBN 0-415-10057-7 , pp. 13-15 .

- Helmuth Schneider : Pig. Classical antiquity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 11, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01481-9 , Sp. 292-294.

- Werner Tietz : Shepherds, farmers, gods. A History of Roman Agriculture . CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-68233-9 , pp. 70-73, 96-97, and the like. a .

Remarks

- ↑ Iliad 9,208; 19,196 f .; 23.32; Odyssey 8.474 ff .; 14.16 ff .; 14.26 ff .; 14.81; 14,414-438.

- ↑ Odyssey 10: 237-243; 10,388-397; 14.5-20; 14,410 ff .; 15.555.

- ^ Richard Hope Simpson: Mycenaean Messenia and the Kingdom of Pylos . INSTAP Academic Press, Philadelphia 2014, ISBN 978-1-931534-75-8 , pp. 47 .

- ^ Aristotle, Tiergeschichte 595a.

- ↑ Aristotle, animal history 545a; 573a-b.

- ↑ Plutarch, Moralia 580e – f.

- ↑ Athenaios 14,656 f.

- ↑ Cf. Polybios 2:15.

- ↑ Information from David S. Potter: The Roman Empire at Bay . London / New York 2004, ISBN 0-415-10057-7 , pp. 13-15 .

- ↑ Varro 2, 4, 13-15; Columella 7,9,9 f.

- ↑ Varro 2, 4, 15; Columella 7,9,14. On the Harae cf. Ferdinand Orth : Hara . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume VII, 2, Stuttgart 1912, Col. 2364.

- ↑ Columella 7,9,6.

- ↑ Varro 2,4,8; Columella 7,9,7; 7,10.6.

- ↑ Varro 2, 4, 22.

- ↑ Varro 2, 4, 21; Columella 7,9,4; 7.11.

- ↑ Varro 2,4,3; Columella 7.1.

- ↑ Varro 2, 4, 19; Columella 7.4.

- ↑ Numbers according to Alexander Demandt : Die Spätantike . Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-55993-8 , pp. 436 .