Sculeni

Coordinates: 47 ° 19 ' N , 27 ° 38' E

Sculeni ( Romanian , in older German texts Skuleni , Russian Скулены ) is a municipality in Ungheni Rajon in the west of the Republic of Moldova , which consists of the four villages Sculeni with 2800 inhabitants, Gherman with 1730 inhabitants, Blindeşti and Floreni. The place Sculeni on the border river Prut is connected by a road bridge with the village of the same name on the Romanian side. The bridge on the Iași - Bălți highway is one of the main border crossings between the two countries.

The Battle of Sculeni, lost by the Greek insurgents of Filiki Eteria in 1821, marked the beginning of the Greek Revolution against the Ottoman Empire . On June 27, 1941, Romanian troops carried out the first major massacre of Jews during the conquest of Bessarabia when they attacked the place on the defensive line of the Soviet army .

location

Sculeni is located around 130 kilometers along the E58 northwest of the state capital Chișinău and around 80 kilometers along the E583 southwest of the largest city in northern Moldova, Bălṭi. On the Moldovan side, a road runs parallel to the Prut upriver north to Costeşti at the Costeşti reservoir and further inland to Edineț . To the south this road leads as the E58 to the district capital Ungheni, 23 kilometers away . The distance to Iași, the largest city in northeast Romania, is 30 kilometers. The Sculeni – Sculeni connection is one of the six road crossings between Romania and Moldova. The first Romanian village Victoria on the road to Iași is five kilometers from the border and has around 1,400 inhabitants. The municipality Sculeni is located in the European region Siret –Prut– Nistru (Upper Prut), which was founded in 2000 . Romanians and Moldovans can visit the neighboring country without a visa. Sculeni lies roughly in the middle of the 684 kilometer long border formed by the Prut. For the Moldovan border region, the cross-border retail trade in fruit and vegetables to the markets of Iași is economically important. Retail trade is cited as the main reason Moldovan villagers in the region travel to Romania, followed by shopping in the neighboring country. The nearest train station is Ungheni (3 hours from there by train to Chișinău).

In its lower reaches, the Prut forms wetlands in several places in the steppe grassland. Shallow lakes near Cahul and Giurgiulești , fed by the river, have been declared protected areas. Such lakes help to compensate for the seasonal fluctuations in water and represent valuable ecosystems for the preservation of biodiversity . Below the Costeşti reservoir, dikes are used in several places along the river, which have been built according to the specifications of the flood protection engineer Anghel Saligny since 1965 and the natural lakes on the banks, the tributaries and marshland turned into arable land. One of these regulated areas is the Trifești-Sculeni dike between Sculeni and the upstream Romanian town of Trifești. Behind the dike, which was built on the river bank between 1972 and 1974, a plain was created that is drained by several canals running parallel to the river and reaching down to the groundwater. The water from the Trifești-Sculeni embankment, which is not required for irrigation, is diverted into the Prut and Jijia , a right tributary of the Prut. The dike between the two places is 30 kilometers long and an average of three meters high. Since the turn of the millennium, investigations have been carried out with the aim of renaturing former floodplains. The average annual precipitation in the region is 500 millimeters (Iași measuring station).

history

Battle of Sculeni

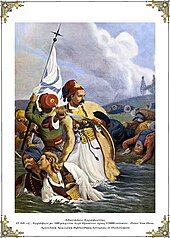

From the beginning of the 16th century, the Principality of Moldova was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire . With the victory of the Russian Empire in the Russo-Turkish War in 1812, Moldova was divided up in the Treaty of Bucharest and Russia moved its previous border on the Dniester westward to the Prut. The rest of the Moldovan territory with the capital Iași remained under Ottoman rule, the eastern half of Moldova with the capital Bender was named Bessarabia and became a Russian province. The Ottomans had installed a Phanarioten government to control the Principality of Moldova. The Greek Phanariotes from Istanbul ruled as administrators ( Hospodar , a prince title) and pressed out a maximum of taxes for the sultan and for themselves. In 1821 there was resistance among the citizens. The leader of the Wallachian insurgents was Tudor Vladimirescu (around 1780-1821). At the same time, the Greeks, organized by the patriotic federation Filiki Eteria , rose up against the Ottoman exploitation. Alexander Ypsilantis , leader of the Greek struggle for freedom since 1920 , started the uprising with an expedition to the Danube principalities north of Greece . Convinced of his success, he crossed the Prut near Sculeni in March 1821 and advanced with his troops to the capital of Iași. The nationally-minded Romanian population, however, refused to support him in the fight against the Turks and instead attacked the hated Phanariotic administrators. On June 19, Ypsilantis "Holy Battalion", as he called it, was defeated by the Turks at Drăgășani . Ypsilantis separated from his troops and fled to Austrian territory.

The remaining Greek insurgents fought yet another battle. On June 29, 1821, a troop of around 500 men, initially led by Gheorghe Cantacuzino, threw themselves into the hopeless fight against the Ottoman army at Sculeni . Cantacuzino saved his life like Ypsilantis before and fled to Russia. During the fighting, around a quarter of the Greeks fled by swimming across the river. The majority died in battle or drowned in the river. The Russian soldiers, who had held back during the uprising, watched the action from the east side of the river and cheered the Greek fighters. The Greek uprising in Moldova was thus suppressed. A major reason for this was that the Romanian population was hostile to the Greeks and always reported their whereabouts to the Turks. The last loyal followers of the commander Giorgakis Olympios , who had been there in Sculeni, withdrew to the Secu monastery near Târgu Neamț , where they were besieged by the Turkish enemy. Olympios, who did not want to fall into the hands of the Turks alive, fought until it was no longer possible, then fired his pistol into the gunpowder depot and died in the explosion. Another revolutionary, Yiannis Pharmakis (1772-1821), held the main building of the monastery for another two weeks before surrendering after a promise of amnesty. The last 20 defenders were shot by the Turks, Pharmakis were taken to Istanbul and publicly beheaded there. This unsuccessful beginning of the revolution for the Greeks with the lost battles of Drăgăşani and Sculeni, however, turned out to be favorable for the Romanians, because Sultan Mahmud II deposed the Phanariots as a result in 1822.

Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837) dealt with the battle of Sculeni in the story The Shot (Russian Vystrel ) from 1830. The deadly battle in which the hero Silvio ends up and then disappears without a trace - as the last sentence of the story says , is interpreted as a metaphor for suicide. Previously, Silvio, who is described as an excellent shooter, abandoned two duels without aiming at his opponent and thus without having restored his honor.

Valentin Petrovich Katajew (1897–1986) refers to Pushkin's The Shot in his story “The Skulyany Cemetery” (Russian: Kladbishche v Skulyanakh , 1975), which has autobiographical traits in an inward-looking presentation style based on a kind of mythical memory. Katajew tells of his great-grandfather, who lived in Pushkin's time and was buried where the hero found death in his story. The author mixes different narrative levels, at one point describes as if he himself had died in Sculeni, only to retire later to the role of a commentator. This can be interpreted as the ideological intention of Kataev to want to create a continuity between the tsarist times of the 19th century and the Soviet Union.

Massacre of Jews in World War II

The state of Romania emerged from the merger of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859, and became independent from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. After 1812, numerous Jewish craftsmen and traders from Poland, the Ukraine and Galicia came to what was now Russian Bessarabia. Around 1900 there were 1,555 Jews in Sculeni. Between the world wars, Greater Romania included Bessarabia. From the end of June 1940 to the end of June 1941, Bessarabia and North Bukovina belonged to the Soviet Union , and the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) was installed on the territory of Bessarabia . Between June 22 and July 26, 1941, Romanian and German troops, united as Axis powers , recaptured Bessarabia, which was ruled without formal annexation.

Two weeks before the major offensive of the German 11th Infantry Division under General Eugen von Schobert was to begin on July 2, it was the task of the 6th Infantry Regiment of the Romanian Army and the 305th German Infantry Regiment (part of the 198. ID ) to set up some bridgeheads on the east bank of the Prut. On June 22, 1941, the operation began with the attack on Sculeni, which was captured on the first day. In the following days, the attackers succeeded in increasing their position around Sculeni. After that, heavy shelling forced the Soviet units to clear the bridgehead again. When the withdrawal from the place itself was imminent and the plan was made to evacuate the residents of Sculeni to the west side of the river, two officers spread the rumor that the place would be attacked from behind and that all the Jews of the village were involved in the attack. From this they deduced the need to identify the Jews among the inhabitants and to murder them. General Gheorghe Stavrescu (1888-1951), commander of the 14th Infantry Division, and regimental commander Colonel Ermil Mateiaş gave their approval. When the villagers were moved to the west bank, a committee began with the participation of those residents who were supporters of the right-wing nationalist politician Alexandru C. Cuza (1857-1947) and Gheorghe Cimpoieș, a member of the Iron Guard and former mayor of the town, identify the Jews and non-Jewish collaborators of the Soviet Union. On June 27, 1941, Romanian soldiers, supported by volunteers from the local community, shot and killed 311 Jewish men, women and children from Sculeni near the village of Stânca Roznovanu. There was disagreement as to whether the non-Jewish pro-Soviet residents should also be shot. For this purpose, an instruction from a higher level was obtained from Iași. The order from there was to release these prisoners, which followed.

About two weeks later, when the Romanians took control of all of Bessarabia, the residents were allowed to return to Sculeni. Those identified as pro-Soviet were charged with high treason in a military court and sentenced to prison terms of varying lengths. The Sculeni massacre became the pattern after which all of Bessarabia was ethnic cleansed and Jews murdered. The Romanian military, Romanian police units and parts of the local civilian population were always involved. The latter were indispensable for the identification of the Jews. In April 1944, Soviet troops invaded Bessarabia again.

At the request of the Jewish community of Iași, three mass graves were opened on September 12, 1945 near Stânca Roznovanu. The adjacent graves were six meters long, four meters wide and 1.7 meters deep. The exhumation of the bodies, which were distributed in roughly equal numbers across the three graves, revealed that only 48 of the murdered were men of military age (between 18 and 40 years old), at least 127 were female and 146 were male. These included at least 45 children under the age of 12 and 46 adolescents under the age of 18. The victims had previously been partially robbed and were mostly scantily clad. Most of the victims had multiple gunshot wounds in the chest, and some had apparently been hit with a rifle butt. The remains were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Iași. The village of Stânca Roznovanu is now called Stânca and belongs to the municipality of Victoria. Since the year 2000 a memorial has been commemorating the massacre on the site.

Since independence

The Moldovan SSR existed until the country declared independence in August 1991. At the beginning of the development that led to the collapse of the Soviet Union , there were the reforms known as perestroika and glasnost , which also affected the Moldovan SSR from 1987 onwards and led to unrest and one that still exists today Led to camp formation. The law passed in August 1989 introducing Latin script instead of Cyrillic for the Romanian language was characteristic of a western orientation in politics. The opening of the border with Romania in 1990 was generally perceived as a liberation. Sculeni and the other border crossings became "flower bridges over the Prut" ( Podul de Flori de la Prut ). Especially the pro-Romanian part of the population spoke of a “euphoria of reunion” when families from both sides of the river were able to visit each other.

Moldova's economic output is significantly lower than that of Romania. According to a survey of selected households in Sculeni in 2008, the mean net income of a household was the equivalent of € 140, with an average of 3.8 people per household this corresponds to € 37 per person. In 2006 the net income was only € 105.

In 2012 Sculeni celebrated the 580th anniversary of the town, which is believed to have been founded in 1432. Sculeni is right on the river bank, opposite the smaller Romanian town. The E58 runs past the western outskirts. The farmsteads are widely distributed between house gardens and arable land around the town center, which forms a tree-lined park. The largest building is the high school ( Liceul Teoretic Sculeni ) east of the park.

population

At the 2004 census, the population of the entire municipality was 5470. Of these, 5139 described themselves as Moldovans , 98 as Russians , 97 as Ukrainians , 90 as Romanians , 16 as Roma , 16 as Gagauz , 4 as Bulgarians and 2 as Jews. The population of the main town Sculeni was 2792. Of these, 2532 described themselves as Moldovans, 85 as Romanians, 73 as Russians, 64 as Ukrainians and 16 as Roma. There were also 2 Gagauz, Bulgarians and Jews. The second largest town Gherman had 1730 inhabitants, followed by Blindeşti with 612 and Floreni with 336 inhabitants.

Sons and daughters of the church

- Eliezer Zusia Portugal (1898–1982), rabbi and founder of a Hasidic school named Skulen ( Yiddish סקולען) is called

- Yisroel Avrohom Portugal (1923-2019), Rabbi; the son and successor of Rabbi Portugal lived in the United States

- Andrei Eşanu (* 1948), historian

- Vichentie Moraru (* 1953), Orthodox cleric, metropolitan

literature

- Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik-Arambașa: Everyday life on the eastern edge of the EU: The population in the border region Romania / Republic of Moldova appropriates space. (Praxis Kultur- und Sozialgeographie, 54) Universitätsverlag, Potsdam 2012 ( full text )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik-Arambașa: Everyday Life on the Eastern Edge of the EU, 2012, p. 62

- ↑ Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik- Arambașa: Everyday life on the eastern edge of the EU , 2012, p. 54

- ↑ Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik-Arambașa: Everyday life on the eastern edge of the EU , 2012, p. 78f

- ↑ Vlad Lăcrămioara Mirela, Bartha Josif, Ilas Ioan, Toma Daniel: Renaturation and Extension Solutions for Wetlands Inside Embanked Enclosures . In: Present Environment and Sustainable Development , Vol. 7, No. 1, 2013, pp. 280–289, here p. 283

- ↑ Lăcrămioara Mirela Vlad, Petru Deliu, Iosif Bartha: Evolution of Water Resources in Floodplains of Embanked Rivers . In: Present Environment and Sustainable Development , Vol. 6, No. 1, 2012, pp. 219–227, here p. 221

- ^ Josif Bartha, Lăcrămioara Mirela Vlad, Daniel Toma, Daniel Toacă, Dorin Cotiușcă-Zaucă: Rehabilitation and Extension of Wetlands within Floodplains of Embanked Rivers. In: Environmental Engineering and Management Journal , Vol. 13, No. 12, December 2014, pp. 3143-3152, here p. 3147

- ^ W. Alison Phillips: The war of Greek independence, 1821 to 1833. Smith, Elder, & Co., London 1897, p. 42 ( at Internet Archive )

- ^ William Miller: The Ottoman Empire and its successors, 1801-1927. With an Appendix, 1927-1936. University Press, Cambridge 1936, pp. 67-70

- ↑ Alexander Pushkin: The shot . ( at Project Gutenberg )

- ↑ Tanja Zimmermann: The Balkans between East and West: Media Images and Cultural and Political Formations. Böhlau, Cologne 2014, pp. 36–39

- ^ Anatoly Efros: The Craft of Rehearsal: Further Reflections on Interpretation and Practice. Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, Bern 2007, pp. 154f

- ↑ Maurice Friedberg: Reading for the Masses: Popular Soviet Fiction, 1976-80. Research Report. International Communication Agency, Washington 1981, p. 27

- ^ Sculeni, Moldova . JewishGen

- ↑ Andrei Brezianu: Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Moldova . (European Historical Dictionaries, No. 37) The Scarecrow Press, Lanham (Maryland) 2000, pp. Xxxiv

- ↑ Vladimir Solonari: Purifying the Nation. Population Exchange and Ethnic Cleansing in Nazi-Allied Romania . The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2010, pp. 168-170

- ↑ Gropile comune de la Stanca. Pogromul de la Iași (Romanian)

- ↑ Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik-Arambașa: Everyday Life on the Eastern Edge of the EU , 2012, p. 71

- ↑ Mihaela Narcisa Niemczik-Arambașa: Everyday Life on the Eastern Edge of the EU, 2012, p. 126

- ↑ Demographic, national, language and cultural characteristics. (Excel table in Section 7) National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova