Seeberg observatory

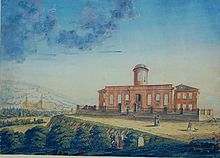

The Seeberg observatory in Gotha was one of the first special observatory buildings in Europe. It was built by Duke Ernst II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg according to plans by the Austrian astronomer Franz Xaver von Zach and was part of the Gotha observatory as a whole . This project also included other research facilities at which a number of scientists were employed.

In 1790 the Seeberg observatory on the Kleiner Seeberg was put into operation. It served as an astronomical observatory until 1839 . Initially equipped with the most modern - mostly English - instruments, it was regarded as a model for other observatories , such as the Göttingen observatory . Under Franz Xaver von Zach it became a center of astronomical information. In 1798 the first European astronomers' congress took place here. From here the first astronomical journals went to all countries.

Planning work

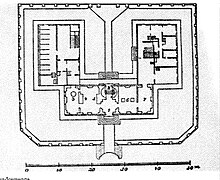

Franz Xaver von Zach was able to convince the duke that towers and tall buildings are not stable enough to set up large telescopes and suggested a building at ground level. He recommended the Seeberg, a quarter of an hour's drive from the castle, as a convenient location. Zach planned a massive observatory building in an east-west direction, which provided space for the installation of two wall quadrants , a passage instrument and the pendulum clocks that go with it . The observations were to be made through crevices in the wall, which allowed a clear view of the north or south horizon. In the middle of the building a small round tower with a rotatable domed roof was to rise above the entrance hall, in which a whole meridian circle was to be set up. Two side wings were intended as the astronomer's residence and for the staff, the guard and stables.

The Duke and Franz Xaver von Zach measured the foundations together. The construction work was entrusted to the Gotha master builder Carl Christoph Besser .

The observatory building

A solid building at ground level was created (as a meridian hall ) with two residential and farm buildings set at right angles. Zach wrote about the observatory in 1789:

- “The building itself consists of an elongated rectangle with a north (1) and a south (2) main entrance, this cuts it into two parts, each of which is again divided into two parts: in one of them there is the passage instrument of eight shoes , with the pendulum clock belonging to it (6), the southern (4) and northern (5) wall quadrants were placed in the second section, and the zenith sector (3) in the third. Since I deliberately did not want to install fireplaces or chimneys anywhere where I have to stand the instruments, the 4th section (7) serves as the living room, in which one can relax in the winter without having to return to the residential building. From this corner room, a small door leads directly into my residential building ... In the middle of the observatory rises above the strongly vaulted entrance, a small tower with a round, movable dome roof, into which a movable whole 8-shoe circle comes ... "

Zach had the pillars of the instruments set up in the natural rock, thus avoiding the measurement errors that resulted from the vibrating components of higher buildings. The main building, the Meridian Hall, was made of Seeberg sandstone and corresponded to the original plans. The quadrants , the passage instrument from Ramsden with a focal length of 2.40 m, the astronomical clocks , including the sidereal time clock from Arnold and the master clock from Mudge & Dutton and numerous other astronomical and meteorological instruments were set up in four rooms . Inside the dome was a vertical circle of carry. The fourth room was the only one that could be heated and was used to warm up the astronomers.

The construction phase lasted from 1787 to 1789. The astronomer lived in the eastern building with numerous rooms and chambers, the service staff, a three-man guard, the horses and carriages were housed in the western farm building. The construction phase ended in 1789, the observatory was put into operation in 1790.

Location of the observatory: 50 ° 56 ′ 1.5 ″ N , 10 ° 43 ′ 41.5 ″ E

Furnishing

With this design and equipment, the Seeberg observatory was the most modern observatory in Germany at the time and one of the most modern research facilities around 1800. Some devices were put into operation upon completion, such as the passenger instrument from Ramsden, the clocks from Mudge & Dutton, from Arnold and Klindworth, smaller telescopes and a heliometer of John Dollond . Over time, the equipment expanded considerably. Duke Ernst II had provided 36,000 thalers for the construction costs and 20,000 thalers for the instrumentation from his "Chatoulle" and tried to secure the preservation of the observatory with a donation of 40,000 thalers. The final equipment did not quite correspond to the above mentioned foresight of Zach. A zenith telescope was not installed.

The foot point of the passage instrument had the coordinates:

Longitude: 10 ° 43 '51 "East Latitude: 50 ° 56' 05" North

These values were later used for land surveying and were the starting point for a precisely measured base route to Schwabhausen. The meridian stone on the Seeberg is no longer in the correct position since the renovation of the current hotel.

The observatory under Zach's direction

Zach's work

As a bachelor, Zach lived in the eastern building, which had a direct connection to the Meridian Hall. He had a household of two female and three male house servants, four horses, an orderly, a sergeant and three guards to secure the facility.

The fame of the observatory spread very quickly and the lively correspondence between Franz Xaver von Zachs made it a popular destination for astronomers at the time. In 1798 the " first European astronomers congress " took place (see below).

Other scientific achievements of the Seeberg observatory under Zach's direction were the rediscovery of the asteroids Ceres and Pallas , the founding of an astronomical society and the further development of geodesy in preparation for the Prussian land surveying. For this purpose, a geodetic base that was also used several times later , the measuring section Seeberg-Sternwarte - Schwabhausen , was precisely defined.

The death of Duke Ernst II on April 20, 1804 initially ended this fruitful work. Franz Xaver von Zach left Gotha as steward of the Dowager Duchess and in 1806 laid down the supervision of the Seeberg observatory.

In 1806, Zach sent the last observatory objects in his possession back to Gotha, where they, like the other instruments, were stored in Friedenstein Castle due to the threat of war.

First European Astronomers Congress

The famous French scientist Joseph Jérome de Lalande had expressed the desire to meet foreign colleagues, especially Johann Elert Bode from Berlin, on the Seeberg . Franz Xaver von Zach extended the invitations to several specialist colleagues, some of whom, however, were not allowed to travel for fear of revolutionary French ideas.

Around 17 European astronomers met in the Seeberg Observatory in 1798 to exchange ideas, demonstrate new devices and methods, and make suggestions for new constellations . A joint excursion to the Inselsberg made practical exercises possible. While the proposals for constellations did not meet with approval, the use of the metric system was considered and a closer cooperation agreed. The latter found expression in the founding of specialist journals, for example in the monthly correspondence published by Franz Xaver von Zach from 1800 onwards for the promotion of geography and celestial science.

This meeting went down in astronomy history as the first European astronomical congress.

The visit of Goethe

In the summer of 1801, Goethe paid a long visit to the Seeberg observatory, which he described as "pleasant and instructive" and which he processed literarily in his 1829 novel Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre .

Young scientists

There was always only one real astronomer employed. Employees were regarded as adjuncts , ie assistants without any real relationship to the court. A number of important astronomers emerged from these adjuncts. So lived Johann Friedrich von Bohnenberger (1765–1831), who later headed the Tübingen observatory , Tobias Bürg (1766–1834), who later worked as a teacher at the Klagenfurt grammar school and from 1792 took over the Vienna observatory as a university professor , as did the Hungarian one Astronomer Johann Pasquich (1753–1829) spent several years on the Seeberg. Johann Karl Burckhardt (1773–1825) worked particularly thoroughly into astronomical science. He later became director of the war school and thus also of the observatory in Paris . Johann Kaspar Horner (1774–1834) from Zurich later made the world tour of Captain Adam Johann von Krusenstern as an astronomer (1803–1808).

Bernhard August von Lindenau's (1779–1834) training was particularly important for Gotha , as it enabled him to succeed Zach in 1804. Mention should also be made of the cartographic education and training Adolf Stieler (1775–1826) at the Seeberg Observatory, which enabled him to create the basis for the development of cartography in Gotha .

Zach's successors as head of the observatory

Bernhard von Lindenau

The work of the Seeberg observatory was initially continued by Bernhard von Lindenau , who had been an adjunct there since 1801 and was later appointed vice director. Lindenau came from Altenburg and was a ducal chamber councilor .

In 1808 Bernhard von Lindenau was commissioned by the now ruling Duke August von Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg to re-establish the observatory and was appointed director of the facility. In May 1808 he was able to report the operational readiness of the scientific facility.

However, structural damage soon became noticeable. In 1810 the tower had to be demolished and in 1811 the two side buildings. On the west side of the meridian hall, a new residential building was built for the astronomer, an adjunct and the castellan . This building was stylistically matched to the main building, the observatory had a completely different appearance. Bernhard von Lindenau put the astronomical work of the Gotha Observatory successfully continued and published in 1810 his Venus tables , 1811's Mars tablets and 1813 tablets of Mercury's orbit . In 1813 the observatory was occupied by the French and many of its papers were burned. The devices were not damaged.

Lindenau was appointed adjutant general of Grand Duke Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach in 1814 and moved with him to Paris , where he was wounded in a duel, so that he could not continue his office.

Friedrich Nicolai and Franz Encke

Friedrich Nicolai was appointed as adjunct of the observatory in 1814 and appointed vice director. He stayed in Gotha until 1816 and then went on to Mannheim as a professor . The former Royal Prussian Artillery Lieutenant Franz Encke took his place .

Like Nicolai and Lindenau, Encke had studied with Gauss in Göttingen . So the three astronomers knew each other and worked well together. When Lindenau returned to Gotha, there was still a year of joint research before he finally had to return to administrative service. From 1816 to 1817 he published the magazine for astronomy and related sciences together with Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger in Tübingen . Even later he published astronomical works.

Johann Franz Encke continued the scientific work. He was appointed vice director in 1818, while Lindenau was appointed curator. Encke calculated here the orbital time of the comet Pons as the shortest known orbital time ( Encke's comet ) and the solar parallax from the Venus passages of 1761 and 1769, which was valid for a long time.

In 1824 Encke married Amalie Becker, the daughter of the Gotha publisher and bookseller Rudolph Zacharias Becker , who also published the publications of the Seeberg observatory and the German national newspaper.

Despite the improvement of the structural and material equipment of the observatory with a Fraunhofer heliometer and an Ertelian meridian circle , Encke accepted the appointment as professor in Berlin . In a memorandum he emphasized that the salary in Gotha was insufficient to maintain a family. In 1825 he therefore accepted the offer to take over the Berlin observatory and left Gotha.

Peter Andreas Hansen

Several astronomers recommended Peter Andreas Hansen as his successor. Hansen was a trained watchmaker from Tondern , but he had worked as Schumacher's assistant in Altona for several years . In August 1825 he arrived in Gotha, where he met Johann Franz Encke at the observatory. From this an understanding cooperation developed for years. An inventory list compiled by Hansen showed the scope of telescopes, measuring devices, clocks and meteorological and geodetic instruments that established the central position of the Seeberg observatory.

Hansen immediately began extensive observations, but also checked the condition of the equipment and gave the conservator the appropriate instructions. But he himself was also bound by the instructions of the curator Carl Ernst Adolph von Hoff (1771–1837), who had been appointed as Bernhard von Lindenau's successor in 1826. Hansen's main focus was theoretical work. He developed into a master of celestial mechanics . The focus was on the movement of the earth's moon , for which he developed precise formulas. This is how his instrumental and celestial mechanical publications emerged in these years.

Meanwhile married and the father of several children, he suffered from the increasing decay of the buildings on the Seeberg and had his own house built in the Siebleber suburb of Gotha . In 1839 he left the Seeberg.

Hansen had to check the old observatory on the Seeberg every week. He noticed the steady decay and now demanded the construction of a new observatory that corresponded to the legacy of Ernst II. He obtained statements from specialist colleagues who supported this project. Even Alexander von Humboldt turned to the Gotha government about this.

In 1856 the Gotha state parliament decided to build a new ducal observatory on the site of the former court smithy using material from the Seeberg observatory (see Gotha observatory ).

Later use and memory

In 1858 the Meridian Hall was demolished. The material was used for a new observatory on Jägerstrasse (see Gotha observatory ). The house served as a restaurant until a fire in 1901. The new building of the restaurant (1904) instead of the former observatory only took over the name "Old Observatory". The Gotha vernacular commented on the building with the humorous rhyme: "The gastronomy follows the astronomy."

Today, two memorial plaques in the outer area of today's restaurant “Alte Sternwarte” commemorate Duke Ernst II as the founder and Franz Xaver von Zach as the first operator of the Seeberg observatory. The so-called meridian stone was also preserved.

literature

- Ernst Jost: The observatory on the Seeberg . In: Rudolf Ehwald (ed.): From the coburg-Gothaischen lands. Homeland papers . Book 3. Perthes-Verlag, Gotha 1905, p. 27-40 .

- Manfred Strumpf: Gotha's astronomical epoch. Geiger, Horb am Neckar 1998, ISBN 3-89570-381-8 .

- Jutta Siegert: The German land surveying of the 18th and 19th centuries, with special consideration of the Saxon-Thuringian area and the maps developed from it . In: Museum for Regional History and Folklore Gotha (Hrsg.): Museum booklet '91. Contributions to regional history . 1991, ISSN 0863-2421 , p. 30-48 .

Web links

Coordinates: 50 ° 56 ′ 1.5 ″ N , 10 ° 43 ′ 41.4 ″ E