Wilhelm Meister's years of traveling

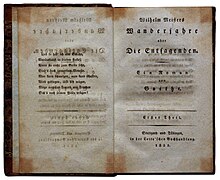

Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre or the Renunciates is a late-completed novel by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe . It is considered the most personal of all Goethe's poems. The first version appeared in 1821, the full one in 1829. It lacks the preceding poems from the fragment from 1821.

Goethe had already written the text between 1807 and 1810. The idea of such a continuation of the apprenticeship years was expressed in the letter of July 12, 1796 to Schiller .

action

Goethe's late work is not a novel according to the technical characteristics, but a station epic about Wilhelm as the central figure with reflections on scientific theories, educational and social models incorporated into the plot. There are also descriptions such. B. the spinning and weaving trade and the cotton home industry. On his wandering, Wilhelm got to know various companies and community facilities, the boards of which introduce him to their action-oriented programs. Accordingly, the education of young people in the Pedagogical Province aims at practical employment. Stories or fairy tales inserted in chapters that address problems of interpersonal moral relationships and v. a. vary the central father-son motif, are thematically linked to the frame story. Accordingly, the narrator in Book 3 describes himself as the editor and editor of the material that he has gradually made available: “So we have come to summarize what we knew and experience at the time, and also what later came to our knowledge In this sense, to confidently conclude the serious business taken on by a loyal speaker. "(III, 14)

first book

First chapter

Wilhelm and his son Felix go on an educational trip prescribed by the spiritual and moral tower society, which separates him as a test from his soul lover Natalie, his “Amazon” of the “apprenticeship years”. At the beginning he writes to her several times, but only once in the second book, and he asks society for an exemption from the contractual clause of constant wandering in order to be able to settle down again.

The Flight into Egypt

In the mountains they meet a family of five who reminds him of the Holy Family, which has been expanded by two boys. The mother with an infant on a donkey, "a gentle, lovable woman", reminds Wilhelm of a painting The Flight into Egypt. The young, sprightly man carries a carpenter's tools. He invites them to spend the night in St. Joseph.

Wilhelm to Natalia

In the evening and the next day, Wilhelm writes to Natalie about his travel experiences. The symbolism is important for the character of their relationship: he has “reached the height of the mountains that will create a more powerful separation between [them] than the entire land area up to now” and he moves in his wandering with the obligation of constant change of location spatially away from her. A “miraculous fate” separates him from her and “unexpectedly closes the heavens that [he] was so close to [...]”. But he sees it as a test for himself. He is on guard against a "commanding conscience" and his "mistakes no longer rush one over the other like mountain waters."

second chapter

Saint Joseph the Second

Saint Joseph turns out to be “a large, half in ruins, half well-preserved monastery building”, “in which the building actually made the residents.” The carpenter has taken over the office of administrator from his father and is in two ways with Joseph -History is connected, as Wilhelm learns after he is led to the restored chapel with a mural. It is a picture story of St. Joseph. Joseph is “busy with carpentry”, he meets “Marien” , and a lily sprouts between the two of them. The life of the host follows this example: out of the gratitude of his parents for their position in the former monastery, he receives the name Joseph and, as a child already influenced by the painting, feels the vocation to become a carpenter.

The Visitation. The lily stem

During the war, he rescues the pregnant widow Marie from marauding soldiers. Soon afterwards she gives birth to “the most beautiful boy” and marries Joseph after the year of mourning.

third chapter

Wilhelm to Natalia

Wilhelm writes to her about the carpenter Joseph: “That adoration of his wife, is it not like the one I feel for you? and doesn't even the meeting of these two lovers have something similar to ours? ”Wilhelm envies Joseph because he lives under one roof with Marie. "On the other hand, I can not even complain about my fate, because I have promised you to remain silent and to tolerate, as you have also accepted."

The two hike on, led by a “mischievous” boy Fitz, and meet Jarno, who is now called Montan and who explains his view of life to Wilhelm. He has withdrawn into the mountains, disappointed by the people: “You cannot be helped.” That is why he follows a “reclusive tendency”. Montan collects stones in the mountains for mining undertakings and tries to capture nature in them, and not in human language or music: "Nature only has one script." You also talk about the natural history instruction of the inquisitive Felix. Montan believes that a teacher cannot convey all of his knowledge to a newcomer. In every new circle one must first start again as a child.

Chapter Four

They continued the educational conversation. While Wilhelm “wants to give his son a more free view of the world than a limited craft can give”, Montan relies on solid experience: “Whoever wants to teach others can often withhold the best of what he knows, but he does must not be half-knowing. ”According to Montan,“ the time of one-sidedness ”- in other words, of renunciation - has dawned, and he also knows the way:“ To serve from below is necessary everywhere. Limiting yourself to one craft is the best. In order to fully own an object, to master it, one must study it for one's own sake. What man is supposed to achieve has to be separated from him as a second self. ”He demonstrates his teaching using the example of a charcoal kiln. Wilhelm is convinced of this and would like to learn a specialty. He asks Montan to help him “that the most annoying of all living conditions [agreement with the“ Society of the Tower ”from the apprenticeship years] not to stay in one place for more than three days will be lifted as soon as possible and he will be allowed to achieve his Purpose there or there as he likes to stop ”.

Wilhelm and Felix continue their pilgrimage to a "giant castle" on a lonely mountain, a labyrinth consisting of walls and columns with caves: "gates to gates, corridors after corridors". Here Felix finds “a small box, no larger than a small octave band, of splendid old appearance” in a crevice, it seems “to be of gold, adorned with enamel”. They meet Fitz again and he leads them on an adventurous, forbidden secret path "to those extensive estates of a large landowner, of whose wealth and peculiarities they were told".

Fifth chapter

“The owner of the house, a short, lively man of years” welcomes Wilhelm and introduces him to his small literary society. a. his nieces Hersilie and Juliette. Hersilie, the eloquently sharp-tongued young woman whom Felix admired, has specialized in French literature and gives Wilhelm a sample of her translation work. Like “The Man of Fifty Years” (II, 3–5), the narrative deals with the father-son theme and is related to the Hersilie-Felix relationship that extends to the end of Book 3:

The pilgrim fool

Herr von Revanne, who lives with his sister and son in a rural castle in the midst of his lands, one day takes in a charming young and educated vagante . During her two-year stay as a partner, she disguised her origins with witty, enigmatic sayings. Father and son fall in love with the mysterious girl and want to marry her. She could thereby secure a social position and is a fool insofar as she does not take the chance. Rather, she puts the two of them to the test and demonstrates their honesty and modesty. She rejects the father's advertisement with the suggestion that she is pregnant by his son. He breaks his promise of secrecy towards her and confronts the son. He suspects a sexual relationship with the father and fears for his inheritance. The beautiful stranger disappears without a trace and teaches them a witty, playful lesson beforehand: “If you don't worry about despising the concerns of a defenseless girl, you will be the victim of women without hesitation. If you don't feel what a respectable girl must feel when you court her, you don't deserve to keep her. Anyone who designs against all reason, against the intentions, against the plan of his family, in favor of his passions, deserves to forego the fruits of his passions and to lack the respect of his family ”.

Sixth chapter

The next day the nieces travel with the guests to a forester's house. On the trip Juliette Wilhelm shows the uncle's agriculture, which is set up according to sensible principles and for healthy nutrition of the population, who lives the “maxims of a general humanity”, which the “striving spirit, the strict character [forms] according to attitudes, which is completely to [relate] to the practical ". It also explains some of the numerous proverbs posted on doors that contain a dialectic, such as: B. “From the useful through the true to the beautiful” or “Possession and common good”, d. H. The rich have to hold the capital together in order to be able to donate the profits, more laudable than distributing everything to the poor is to be their administrator. On the other hand, the uncle's business is not geared towards increasing profits: "[T] he lower income I see as an expense that gives me pleasure by making life easier for others."

Hersilie also tells Wilhelm about Makarie, "a worthy aunt who, living near her castle, is to be regarded as a protective spirit of the family" and of cousin Lenardo, who for three years made his way through Europe only by traces without written notice the gifts, such as fine wines or the Brabant lace. Hersilie gives Wilhelm an insight into Lenardo's correspondence with aunt and nieces with the comment: "Yesterday I introduced you to a foolish country runner, today you are supposed to hear from a mad traveler."

Leonardo to the aunt. The aunt to Julietten. Juliette to the aunt. Hersilie to the aunt. The aunt for the nieces. Hersilie to the aunt. The aunt to Hersilien.

Leonardo announced his return to his aunt and explained his three years of silence: "I wanted to see the world and surrender to it, and for this time I wanted to forget my home, from which I came, to which I hoped to return". He was coming home "from a foreign country like a stranger" and asked you for detailed information by letter about the family situation and the recent changes in the house and farm. The nieces asked by the aunt for writing help, v. a. the eloquently ironic-sharp-tongued Hersilie, react to this with criticism, also of the blind good nature of the aunt towards her “spoiled” nephew: “Keep it short [...] There is something measured and presumptuous in this demand, in this behavior, like The gentlemen usually have it when they come from distant countries. They always think that those who stayed at home are not full. "

Wilhelm to Natalia

Wilhelm describes this correspondence as typical of the “writability” of the educated women of his time: “In the sphere in which I am currently, one spends almost as much time communicating to relatives and friends what one is concerned with as you had time to occupy yourself ”. So he knew about "the people whose acquaintance [he] will make [...] almost more than they themselves".

Seventh chapter

The family story of the landlord is told: He was born in North America, but did not want to build a society based on the principle of competition and profit like his father and did not want to participate in the expansion of the area to the west in the fight with the Indians, but took over in old, traditional Europe family goods and organized them amicably with the neighbors according to the tolerance requirement of an enlightened religion. In the 3rd book (14. Kp.) He leaves his overseas leased properties to Lenardo and Friedrich for use by their company.

Eighth and Ninth Chapters

The following story, which, like that of the “fool”, teaches about trustworthy human interaction among friends, is built into the Wilhelm story while he is traveling to Makarie's with Felix.

Who is the traitor?

The senior bailiff in R. and his friend Professor N. plan to arrange a marriage between their children Julie and Lucidor and at the same time prepare the son-in-law as successor for the office without informing those involved. So the professor moves his son to study law, and the lively, childlike daughter Julie receives geography lessons in the professor's house. After the children have been initiated into the plan, Lucidor spends a few weeks in the house of the bailiff to get closer, but falls so much in love with his second, more mature and domestic daughter Lucinde that he trembles when she “with her full , pure, calm eyes ”. However, as it appears, it is being courted by a house guest, the world traveler Antoni. Now a game of confusion begins. Lucidor is "of deep mind", does not dare to confess his inclination, and expresses his feelings in loud monologues in his bedroom. The family hears his words of love through the wall. The daughters agree to the change, as Julie feels more drawn to Antoni, even if she is a little annoyed about the rejection. Lucidor is only released from his suffering shortly before the happy end, after Lucinde prevents his attempt to escape with her confession of love. Because first the fathers had to discuss the new situation. He suspects treason behind the delay, but learns from Julie that he was his own traitor through his monologues. During this interview during a carriage ride she had arranged through his new district, she made her virtuoso appearance, apparently as the narrator's mouthpiece: She criticized the agreement of the fathers without asking the children, as well as Lucidor's timidly weak role in clarifying the situation, d. H. To hold solitary monologues instead of dialogue - and accordingly this scene is executed as a dialogue. Julie ironizes the entire bourgeois concept of life of the lawyer, who is concerned with securing the standard of living and sedentarism, and his noble Lucinde to match. On the other hand, she would like to get to know the world with Antoni.

Chapter ten

The next stop on Wilhelm and Felix's wandering is Makarie's Castle, which has a pen, a kind of household school for young girls to prepare them for “active life”, an archive with Makarie's records and a collection of quotations and an observatory managed by the young, beautiful Angela are connected. There the astronomer shows the guest the starry sky with a telescope, but for Wilhelm it is more of a disadvantage to zoom in on Jupiter or Venus, because he wants to see the "heavenly host" as a whole and with the image of the universe in compare his inner being. In this respect Makarie is soulmate with him, but far superior to him, because she is able to grasp the deepest secrets, as Angela explains to him: “As one says of the poet, the elements of the visible world are inwardly hidden in his nature and have each other only to develop from him little by little so that nothing in the world comes to him to look at that he had not previously lived in the premonition: just as it would seem, the conditions of our solar system are Makaria from the beginning, first dormant, then they are gradually developing, furthermore becoming more and more clearly invigorating, thoroughly innate ”. These premonitions are the basis of her knowledge of human nature, which she passed on to Wilhelm when she said goodbye to Baron Lenardo, whom she characterized as follows: “By nature we have no fault that does not turn into a virtue, no virtue that cannot turn into a fault. These last are the most questionable ”.

Eleventh chapter

The nut-brown girl

Lenardo tells Wilhelm the story of his agony of conscience, which resurfaced on his return home. His educational journey "through the decent Europe" was financed by the fact that his uncle had outstanding and previously deferred leases collected. A tenant, a pious man who could not run the farm, therefore had to leave the farm. His daughter, called the “nut-brown girl” because of her “brownish complexion”, asked Lenardo to try to get another respite for her insolvent father from her uncle. Moved by the crying girl, he carelessly agreed to "do what is possible". Although he spoke to the charge d'affaires, he was unable to achieve anything and after his departure suppressed the promise. Now he returns feeling guilty, and he is relieved to learn that Valerine, he thinks he remembers this name, is now married to a wealthy landowner. He drives to her with Wilhelm and when he sees the blonde woman he realizes that he has mixed up the names of two playmates from his childhood. The nut-brown girl is called Nachodine. Lenardo now asks Wilhelm to look for her and possibly to support her financially.

Chapter Twelve

Before Wilhelm carries out his assignment, he visits the "old man", named by Lenardo as a mediator, who collects and stores used items for the grandchildren in his house, and gives him the locked precious box found in Felix's "giant castle" to keep. This means, "if this box means something, the key to it must occasionally be found, and precisely where you least expect it". He also gives Wilhelm information on Nachodine's whereabouts and recommends a special educational facility for Felix: “All life, all activity, all art must be preceded by the handicraft that is only acquired when limited. Knowing and practicing one thing right gives higher education than half a hundred fold. "In the educational province every pupil is tested," [w] o his nature actually strives [...] wise men let boys [...] find what suits him , they shorten the detours through which a person may stray from his destiny only too accidentally. "

second book

First and second chapters

Before he looks for Nachodine, Wilhelm brings Felix for training in the "Pedagogical Province", a remote, idyllic, fertile rural area where the boys live like on an island utopia and can develop their facilities as freely as possible. So they may z. For example, they can choose their own clothes according to cut and color, and their educators recognize certain characteristics such as individual creativity or a tendency to form groups. Wilhelm learns some educational goals from “the superiors”, “the three”, although not everything is revealed at the beginning: the secrets are to be revealed only gradually. The basis of education is music, v. a. the choral singing, on which the writing of the notes and the text is based. In this way one practices from the sensual to the symbolic and philosophical "hand, ear and eye" in connection with one another. In particular, the young people, supported by different ritual gestures, learn the threefold reverence: for God, the world and people. The “true religion” unites these three areas and culminates in the highest level, “reverence for oneself”. In this context, the students have a lot of freedom, but they have to adhere to the rules, but "[if] he does not learn to obey the laws, he has to leave the area where they apply".

In an inner area closed off by a wall, the oldest Wilhelm shows two galleries in the second chapter, which the pupils are also allowed to see in their lessons: the first depicts "the general outer worldly" in historical events of the Israelites and compares them thematically with mythologies other cultures. The second room shows legends from the life of Jesus up to the Lord's Supper as “the inner, especially spiritual and heartfelt”. The third picture hall remains closed to Wilhelm. It is the "sanctuary of pain". "That admiration of the repulsive, hated, fleeing" is not part of the compulsory program and is "only given to everyone in the world, so that they know where to find such things if such a need should arise in them."

Third through fifth chapters

Another narrative, whose "people [...] have been intimately woven with those we already know and love," is inserted into the plot. It is about the love entanglements within a group of four, which resolve at the end of the third part (III, 14).

The man of fifty

The major and his sister, the widowed baroness, have rearranged their property, paid off the second brother, the chief marshal, and are planning to marry his son Flavio and their daughter Hilarie. But now the baroness tells the major that Hilarie loves him, the uncle, “really and with all her soul”, and she has nothing against her brother, who is young at heart, as a son-in-law. On the one hand, the major is shocked, on the other hand, he feels flattered as a fifty-year-old, thinks about his age and appearance and accepts an offer from an old friend who happens to be visiting him to try a makeover that he uses as an actor. To do this, he leaves him his “rejuvenation servant” and his “toilet box” for some time. Through the concentration on his person associated with the treatment, the major gains increased self-confidence, “a particularly cheerful sense” and he confesses to Hilarie: “You make me the happiest person under the sun! Do you want to be mine? "She agrees," I am yours forever. "

The major now visits his son with a bad conscience to talk to him about the difficult situation and to find out his ideas. But the problem seems to be resolving before it is addressed, as Lieutenant Flavio admits he loves a beautiful widow. He suggests to the father that he should start a new life with Hilarie and thus keep the family property together. He agrees, relieved, and Flavio introduces the widow to his father. She is already well informed about him, on his farewell visit in Chapter 4 she asks him about his poems, which he writes down in his spare time, and asks him to send her some poetry samples, in one of her artfully for a special one Wallet made by the person, which she gives him as a souvenir token.

In chapter 5 the situation escalates: The beautiful widow apparently playfully lured Flavio in her vanity at first and turned him away when she feared his persistence. Thereupon he falls into a crisis and flees sick from the garrison to his aunt. During the nursing leave he complains to Hilarie of his suffering and she reads his love poems to the widow with him and sets them to music. This is how he processes the separation and, conversely, his cousin thinks about the role of the courted one. The rapprochement between the two is strengthened by excursions together and ultimately develops into a love affair that culminates in the winter when they go ice skating together in the moonlight, which the major has to watch on his return. His age reflections are activated again, confirmed by a tooth loss, but to his astonishment he reacts with composure, because he was “through half consciousness, without his will or aspiration, already deeply prepared for such a case. […] He felt the uncomfortable transition from first lover to affectionate father; and yet this role wanted more and more to impose itself on him. ”He processes the solution to the relationship problem in a poem:“ The late moon, which still shines properly at night, fades before the rising sun; the madness of old age disappears in the presence of passionate youth ”. He has already changed the cosmetic makeover to a new awareness of a healthy and moderately balanced lifestyle, and the consultant was able to return to the actor. Although he is still rationally and emotionally divided, he explains to his sister that he agrees to a marriage between Flavio and his cousin, and she tries to convince her daughter of this with reasons of reason, but Hilarie is not yet ready to do so in her emotional confusion.

While she was caring for her nephew, the baroness noticed that her daughter's inclination was “about to turn around”, and because of the tensions that were to be feared in the family, she turned to her old friend Makarie for advice, who in turn spoke to the beautiful widow about Flavios Disease corresponds. The latter asks the major for an interview and regrets her part in the confusion caused by coquetry. This connection of the narrative with the general plot is continued in the 7th chapter under the topic "the renunciation" and in the 3rd book (14th chapter) with the solution.

Sixth chapter

Wilhelm to Lenardo, Wilhelm to the Abbé

Wilhelm informs Lenardo and, in a duplicate, the Abbé that he found Nachodine in good circumstances, but that he does not reveal her whereabouts in order to prevent Lenardo from going at penance. He repeated to the Abbé his wish to change the conditions for his wandering so that he could stay in one place for a longer period of time.

Seventh chapter

On his wandering Wilhelm comes to a spiritual and artistic district, actually a landscape of souls that takes him back to the "years of apprenticeship". He finds a young travel companion who visits Mignon's “surroundings in which she lived” and paints pictures of her. At the idyllic lake, they meet Hilarie and the beautiful widow. They are now also on the move as "renunciates". Hilarie's heart is still wounded, but “when the grace of a wonderful region surrounds us soothingly, when the mildness of soulful friends affects us, something of its own comes over spirit and meaning, which calls back to us the past, the absent and the present as if it were it is only an appearance, spiritually distant. "Stimulated by the artist, Wilhelm learns a new way of seeing and looks at the Alpine landscape like a great painting by the great creator, and Hilarie begins to paint herself and this is" the first happy feeling that in Hilaria's soul after some time [emerges]. To see the wonderful world in front of you for days and now to feel the complete power of representation that has suddenly been given. ”In the paradisiacal natural landscape and during boat trips on the gently undulating lake, the four of them form a community of souls for a short time before they part with the promise to part not wanting to meet again.

Lenardo to Wilhelm, The Abbé to Wilhelm

Lenardo thanks Wilhelm for good news, and the Abbé reports on the plan to populate a newly created canal with craftsmen and to promote pedagogy: “[W] e have to grasp the concept of world piety, our honest human sentiments in a practical context and not only promote our neighbors, but at the same time take all of humanity with you. ”He also informs Wilhelm that the Order fulfills his wish:“ You are released from all limitations. Travel, hold up, move, hold up! what you succeed will be right; would you like to become the most necessary link in our chain. "

Intermediate speech

The plot jumps by a few years in the next chapter.

Eighth chapter.

Wilhelm visits Felix in the "Pedagogical Province" - and thus the plot follows on from the beginning of the 2nd book - and finds out about his development and the broad educational concept: In the first, rural district with scattered hut-like buildings, learning is concentrated agricultural work, e.g. B. Plowing and tending to cattle and horses. This is supplemented by monthly changing language lessons for the international student body in order to prevent the formation of country teams, and choosing a focus, Felix is learning Italian. Singing, instrumental music, dance are associated with poetry exercises. In the second district lies a city that is constantly expanding due to the construction work of the students and their masters. Fine arts and crafts, as well as epic poetry, are taught here through their own designs.

Chapter ninth

At the end, Wilhelm meets Montan (I, 3 and 4) again at a nightly festival. As a “whimsical spectacle”, he sees the network of subterranean crevices in the mining area from above, as if illuminated by lava flows. There is a discussion about the different possible origins of the earth and the mountains, etc. a. the Flood and Volcanism interpretations. Montan keeps out of the theoretical dispute between the supporters of Neptunism and those of Plutonism , which is not very meaningful for him , and explains his view: "T] he dearest, and these are our convictions, everyone has to keep to himself in the deepest seriousness [...] as he pronounces it, the contradiction is immediately lively, he comes out of balance in himself and his best is, where not destroyed, but disturbed. ”His solution is the combination of“ doing and thinking, that is the sum of all wisdom. […] Both, like exhaling and inhaling, have to move back and forth forever in life […] Whoever makes himself law […] examining doing by thinking, thinking by doing, cannot be wrong, and he is wrong so he will soon find his way back on the right path. ”He doesn't even want to know how the mountains came into being, but he strives daily to extract their silver and lead from them.

Chapter ten

Hersilie to Wilhelm

Hersilie informs Wilhelm that the surprising confession of love that Felix sent her from the “Pedagogical Province” had flattered her, but at the same time made her confused and thoughtful: “Indeed, there is a mysterious tendency among younger men to older women”. This topic is continued in the 3rd book (III, 17) and also dealt with in the two narratives inserted into the novel: In Die Pilgerung Törin (I, 5) and in The Man of Fifty Years (II, 3–5) the Love of complications between father and son.

Eleventh chapter

In Wilhelm's last letter to Natalie, at the end of the second book, he writes about his carefully matured decision to learn the craft of a surgeon .

Wilhelm to Natalia

Wilhelm informs Natalie that he wants to become a surgeon in order to join Natalia “as a useful, as a necessary member of society” because of […]; with some pride, because it is a laudable pride to be worthy of [her]. ”Jarno (Montan) convinced him that one needs people in life who have special practical knowledge:“ foolish antics ”, on the other hand, are his“ general education and all arrangements for it ”. He explains this tendency to become a doctor to Natalie through a series of key experiences that go back to his childhood. On a family trip to the outskirts of the city, he saw some boys drowning cancer catching in the river and perhaps could have been saved if a surgeon could bleed and resuscitate them. Since his own injury during his “apprenticeship years” when Natalie found him in the forest, his fetish has been a box with surgical instruments in his luggage.

Considerations in the interests of hikers

Art, ethical, nature (see quotes )

Third book

The central theme of “wandering” is expanded to include “emigration” to overseas in the third book. Many people from the “apprenticeship years” appear in this context.

First chapter

Wilhelm approaches "the allies" again, he wanders through a hilly natural landscape and comes to a castle where, as head of the emigrant community "Das Band", he meets two old friends: Lenardo and Friedrich, Natalie's brother ("apprenticeship years") . They prepare craftsmen willing to emigrate for their new life and, just after a feast with traveling songs, they say goodbye to a group with the choir singing: “Don't get stuck on the ground, freshly daring and fresh out, head and arm with cheerful strength They are at home everywhere”.

second chapter

Hersilie to Wilhelm

Hersilie has found the key to the box (I, 4) and invites Wilhelm and Felix to open it.

third chapter

Wilhelm has to refuse Hersilie's invitation because he is treating the community's craftsmen as a surgeon. In the evening discussion, he tells them about his anatomy training on prepared body parts and about the idea of an artist influenced by ancient sculptures to replace them with wooden and plaster models in order to preserve the dignity of the dead. The master hopes to implement his method in schools overseas. Lenardo and Friedrich want to support him in their institutions , despite the resistance of the traditional prosectors .

Chapter Four

Friedrich tells Wilhelm after his report about his training that some frivolous people of the “apprenticeship years” have become solid according to the “basic law of our connection: someone has to be perfect in some area if he wants to make a claim to cooperative society.”: Lydie, the former Beloved Baron Lotharios, is now Jarnos (Montan's) wife and works as a seamstress. Friedrich married the actress Philine, who was involved in many relationships, and she became a tailor. He himself no longer uses his good memory for theater texts, but for administrative work and the logging of conversations, as in III, 9 and 10. Then Lenardo reports on his early inclinations towards the carpentry trade, his “drive for the technical”, and gives Wilhelm a part to read his diary. The continuation follows in III, 13.

Fifth chapter

Lenardo's diary

During his travels, Lenardo accompanies a yarn carrier to the cotton spinners and weavers in the mountains, who are increasingly competing with “mechanical engineering”. It describes in detail with technical terms the devices and their operation as well as the connection of home work with the publishing system of the dealers in the valley. He characterized the atmosphere in the homes of the craftsmen who could become useful members in his emigrant society as “peace, piety, uninterrupted activity”. He ironically recommends turning the spindle to "our beautiful ladies" who "shouldn't fear losing their true charm and grace if they wanted to use the spinning wheel instead of the guitar".

Sixth chapter

The barber Rotmantel joins the evening gathering of friends and tells the following fairy tale, which adds a fabulous prehistory to the box found in the framework story (I, 4 and 12, III, 2 and 7):

The new Melusine

The plot, which is presented by the stray protagonist in the first person, plays with the Melusine motif. In its ironic modification, a dwarf princess falls in love with the dissolute and therefore constantly struggling traveler. She has chosen this as the father of her future child in order to refresh the genome of her degenerated, ancient family. In addition, she lives alternately in two sizes in two worlds. With a magic ring she can enlarge and appear in human society as a beautiful singer and lute player who is charming for men. In miniature, it disappears into her castle, which the lover who travels with her and who she has provided with an inexhaustible gold pouch transports it from place to place as a box with the carriage. When her mission is fulfilled and she returns to the dwarf kingdom pregnant, her friend, who has also shrunk, accompanies her and is married to her. But he cannot stand the tension between the perceived inner greatness, the ideal of himself, and the small figure, files the magic ring that sits tight on his finger in two and returns numbly to his old world. Next to him, when he wakes up, he finds the box filled with gold, which he sells for want of money after emptying it lavishly.

Seventh chapter

Hersilie to Wilhelm

After the antiquarian's death (I, 12), Hersilie is now in possession of both the key and the box and asks herself about the significance of this coincidence or coincidence and its role in it. She asks Wilhelm and Felix again (III, 2) to visit them and help with the interpretation “what is meant by this wonderful finding, reunion, separation and union”. Only Felix will accept this invitation and, like Flavio, appear uncontrollably with the beloved (III, 17).

Eighth chapter

In a further evening round, St. Joseph, Lenardo's extremely strong porter, recounts the self-experienced swank “The dangerous bet” to loosen up.

The dangerous bet

When he was traveling through the country with a group of high-spirited drinking students, he made a whim and made a bet with them that he could "pick the nose of an old gentleman who had also stayed at the inn without doing anything bad". He pretended to be a barber and could perform his prank while shaving. But the mocked found out about it and wanted his servants to punish the students, who were able to flee. The reckless act had unpleasant consequences, however, when the offended man died and his son blamed the group for it. He dueled one of the students, wounded him, and got into trouble himself from subsequent events.

Chapter ninth

Lenardo gives a speech to the meeting on the history and goals of the emigration. Merchants, pilgrims, missionaries, scientists, diplomats, government officials etc. have always changed their place of work and residence, thereby expanding their knowledge of the world. Now, through the reports of the seafarers, one has a good overview of the living conditions in the sparsely populated continents and there is the possibility for farmers and craftsmen of overpopulated Europe to improve their own lives and to help their new home through their services, according to the motto “Where I use, there is my fatherland.” Every participant in the meeting should ask himself the question of where he can best use and then decide whether he would like to emigrate or stay.

Chapter ten

Odoard joins the meeting as a guest. In the following, Odoard's intricate relationship story is told on the basis of Friedrich's memory logging from changing perspectives.

Not too far

As a talented, well-educated offspring of an old family, Odoard made a career in the civil service and married the daughter of the first minister. The marriage with the beautiful Albertine, who enjoys social splendor as the focal point of large celebrations, is disturbed by rumors about his infatuation with the wealthy princess Sophronie, indicated in an "Aurora" poem, whose prince-uncle she wants to marry off to the hereditary prince, while the neighboring one old king apparently pursued other interests. Odoard seems to support the second possibility, therefore falls out of favor at court and is transferred as governor to the province, where his wife misses her courtly appearances, but they come to terms. The tension is discharged on Albertine's birthday, which she celebrates with friends on the manor of the lively, teasing Florine. When the party is out for a ride, her car slips into the ditch and she misses the family dinner and the presents from her husband and children. Even more than the absence of Odoard, who has left the house angrily, she suffers from the discovery after the accident that her household friend Lelio, whom her husband tolerated, is having an affair with Florine. Odoard, on the other hand, has stopped at an inn, happens to meet Sophronie there, who is waiting for her uncle, and speaks to her confused with Aurora.

Eleventh chapter

Wilhelm agrees with Friedrich's plan for a new society: u. a. Adoption of the advantages of the previous culture and exclusion of the disadvantages, validity of the majority principle, despite some criticism, no capital, but, as in the Middle Ages, roving authorities in the empire, from the beginning mild laws that can be tightened if necessary, exclusion of lawbreakers from civil society, a practical moral doctrine based on the values of the Christian religion, v. a. Prudence, patience, "moderation in what is arbitrary, diligence in what is necessary".

Chapter Twelve

Odoard presents his settlement project in the Old World, an alternative to emigration to the New World: "Stay, go, go, stay, from now on be equal to the brave, where we do useful things. The most valuable area:" Craftsmen and farmers could go into the remote, sparsely populated provinces, of which he is the governor, to carefully build a new society out of the old one. The time is right; There was agreement about the purposes of the reform, “much less often about the means to get there”: “The century must come to our aid, time must take the place of reason, and in an enlarged heart the higher advantage must lower the lower displace ".

Chapter thirteen

The continuation of the diary (III, 5) has arrived and Wilhelm is reading the second part of Lenard's notes.

Lenardo's diary - continued

On his mountain tour Lenardo finds out more about the publishing of cotton textile production and the connection between home workers and traders. Among the weavers he finds junior women and their sick father, for whose expulsion he feels responsible (I, 12). At that time they had been accepted by a religious community in the mountains. Nacholdine made friends with a weaver boy and trained with him in a philosophical and literary way beyond the formulaic language of her community. He became her bridegroom, as advised by a guest - Wilhelm, as Lenardo knows (II, 6) - and they planned a life overseas. When he fell ill and died before the wedding, the wealthy in-laws took her in instead of their daughter, who had also died, and called her Susanne. For Lenardo she is the "beautiful lady". She tells him about the danger of unemployment and impoverishment of the population due to the increasing use of machines and her dilemma of moving away or staying and saving her family business through modernization, but thereby exacerbating the social consequences of development. She wanted to emigrate with her fiancé. Your helper Daniel wants to stay and mechanize the looms. As a friend of her bridegroom, he has suppressed his love for her, now he reveals himself and wants to marry her, but she cannot reciprocate his feelings. When he sees Nacholdine together with Lenardo on her father's deathbed, he offers her to emigrate together and complicates the decision for her. As the narrator reports in the next chapter, she soon breaks up the relationship, leaves the mountains and takes over Angela's position with Makarie. She leaves her property to Daniel, who can use it to invest in mechanization according to his earlier plan. He marries the second daughter of a wealthy family and becomes the brother-in-law of the designer of new weaving machines, the so-called “harness barrel” (III, 14).

Fourteenth Chapter

The narrator ("We, however, from our narrative and performing side") gives an overview of the actions and the dissolving and reorganizing relationships of the people who are no longer the focus at the end of the "wandering years" and who are accommodated in advantageous relationships. While Lothario, his wife Therese and Natalie, "who did not want to leave her brother from her", accompanied by the Abbé go on a sailing ship to the New World and Montan, Friedrich and Lenardo took over the property of their uncle (I, 7) are allowed to use, prepare for their journey, characters from the “apprenticeship years” and “wandering years” meet at Makarie: Hilarie with her husband Flavio, the son of the major, who “with that irresistible” (refers to the “beautiful Widow ”in: The man of fifty years : II, 3–5) is married, Juliette, also married, Friedrich's and Montan's wives Philine, with their two children, and Lydie (III, 4),“ the two sinners at the feet of Holy [Makarie] ”. The astronomer ("ethereal poetry") agrees with Montan ("terrestrial fairy tale") about the complementary connection between their two areas of investigation in the plan of creation. Angela will marry merchant Werner, Wilhelm's friend, talented assistant. Nachodine takes on her job as Makarien's archivist (I, 10), who needs time to process her fate for a possible new beginning. Lenardo hopes to be able to bring her to the New World one day.

Chapter fifteen

Makarie's “ethereal poetry” is explained as the relationship between her cosmic, all-embracing soul and astronomy or astrology: “In the spirit, the soul, the imagination, she not only sees it, but also makes a part of it; she sees herself drawn away in those heavenly circles [...] since childhood she has been walking around the sun [...] in a spiral, moving further and further away from the center and circling towards the outer regions. ”Through her encounter with“ heavenly comrades ”has they have visionary abilities from the planetary system.

Sixteenth Chapter

The bailiff of the district in which those willing to emigrate met pursues his own purely commercial goals after the community has withdrawn. He recruits undecided handicraftsmen for a newly founded furniture factory, with the offer to settle down and marry a daughter of the country. When Felix rides stormily into the quiet town looking for his father, he is told that “he has embarked on the river a few miles away; he goes down to visit his son first, then to pursue an important business. "

Chapter seventeenth

Hersilie to Wilhelm

Hersilie writes to Wilhelm about his son's visit and sends the letter to the city, which the addressee has already left. Felix broke the key while trying to open the box and then harassed her. In her confusion she first returned his kisses, then, coming to her senses, rejected him and sent him away. He then threatened: "[S] o I'll ride into the world until I perish." She is now worried about him and asks Wilhelm to look for him. She reproaches him: "Were there not enough of the father who caused so much harm, does it still need the son to confuse us indissolubly?" Her ambivalent relationship with father and son, Wilhelm's reluctance towards her as well the uncertainty of their future is reflected in the history of the box. A goldsmith recognized the magnetic effect of the key, but he warns her to open it, "It is not good to touch such secrets".

Chapter eighteenth

From the ship, Wilhelm sees a rider falling down the steep river bank into the water and drowning. Since Hersilie's letter did not reach him, he only recognized Felix, who was looking for him, when he was rescued. He revives it by bloodletting (II, 11). The third book closes with the father-son covenant. Felix calls: “If I am to live, so be it with you! [...] They are firmly embraced, like Kastor and Polux , brothers who meet on the path from Orcus to Light. "At the sight of the sleeping son, Wilhelm reflects on creation:" If you are always brought forth anew, glorious image of God! [...] and are immediately damaged again, injured from the inside or outside. "

From Makarien's archive (see quotes )

characters

Figures from Wilhelm Meister's apprenticeship years

Figures are in alphabetical order. The number indicates the page on which the name is mentioned first. During the "wandering years" they learned practical professions and, apart from Werner and Wilhelm, are preparing for their emigration.

- 528 In the background, the Abbé directs Wilhelm's fate.

- 388 Felix is the son of Wilhelm.

- 587 Friedrich , the brother of Natalies and Lotharios, is in the "wandering years" member of the community of emigrants "Der Bund" as well.

- 539 Baron Lothario is a member of the Tower Society, Natalie's and Friedrich's brother and is married to Therese.

- 664 Lydie , Lothario's former lover, is Montan's wife during the "wandering years" and has trained as a seamstress.

- 402 Montan (the Jarno from his apprenticeship years ) works as a geologist.

- 390 Baroness Natalie is Wilhelm's lover of soul and Lotharios and Friedrich's sister.

- 664 Philine was an actress who became pregnant by Friedrich at the time, they are married in "traveling years", she works as a tailor.

- 662 Therese is Lothario's wife.

- 668 The merchant Werner is Wilhelm's childhood friend.

- 388 Wilhelm (see plot ) is the central figure as a wanderer.

New figures

- 415 Hersilie renounces, is the younger niece of the master of the house.

- 430 Baron Lenardo is Hersilie's cousin.

- 435 Makarie, Lenardo and Hersilie's aunt, is “an elderly, wonderful lady”. Behind her is the Duchess Charlotte von Sachsen-Meiningen , wife of Ernst II. Von Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg .

- 635 Odoard is "a man of engaging nature" who is pushing a settlement project in Europe.

Minor characters

- 458 Angela is the Makaries archivist. She marries Werner's employee.

- 458 The doctor, mathematician and astronomer is a collaborator in Makaries. Behind him is the Gotha court astronomer Franz Xaver von Zach , to whom Goethe created a subtle memorial in the novel.

- 415 Juliette is Hersilie's older sister.

- 433 Nachodine is the daughter of a dissolute tenant at the castle. You have to emigrate to the mountainous country and work as a weaver. Eventually Lenardo brings her back and after Angela's marriage she becomes Makaries archivist.

- 415 Lenardo and Hersilie's uncle (uncle) is the master of the house.

- 433: Valerine is the daughter of the bailiff at the castle.

- 416 Herr von Revanne is a rich provincial man who takes in the pilgrim fool for two years, falls in love with her and is teased by her.

- 416 The pilgrim fool is an allegory of poetry who lives as a companion in the castle of Herr von Revanne for two years.

- 441 Antoni is "no longer young, of considerable prestige, worthy, lively and extremely entertaining thanks to his knowledge of the furthest regions of the world".

- 439 Julie has been chosen as the bride for Lucidor by Professor N., but she marries Antoni.

- 439 Lucidor is the son of Professor N. zu N. His patron is the Oberamtmann zu R. He falls in love with Lucinde and marries her.

- 439 Lucinde is Julie's sister.

- 491 The baroness is the major's sister and the mother of Hilarie.

- 514 Lieutenant Flavio is the major's son.

- 491 Hilarie is the daughter of the baroness.

- 491 The major is the title character of the novel.

- 501 The beautiful widow turns Flavio and his father's heads.

Quotes

From the factory

- (1,3) Joseph: "Whoever lives must be prepared for change."

- (1,3) Montan: "Good things take time."

- (1:10) Wilhelm: "Whoever sees through glasses thinks himself smarter than he is."

- (1,11) Lenardo: "The sons of heroes become good-for-nothing."

- (1:12) The old man to Wilhelm: "Whoever lives long sees some things gathered together and some things fall apart."

- (2,3) The friend to the major: “One wants to be and not seem. That's pretty good as long as you are something. "

- "Everything that is clever has already been thought, you just have to try to think it again."

- “How can you get to know yourself? Never by looking, but by acting. Try to do your duty and you will immediately know what's up to you. "

- “But what is your duty? The demand of the day. "

- "Excellent painters have emerged from painters."

- “Tell me who you deal with, I will tell you who you are; if I know what you're doing, I know what can become of you. "

- "A big mistake: that you think yourself more than you are and value yourself less than you are worth."

- "People who think deeply and seriously have a bad stand against the audience."

- “If I am to hear someone else's opinion, it must be expressed positively; I have enough problematic things in myself. "

- "I keep quiet about a lot of things, because I don't like to mislead people and I am probably satisfied when they are happy where I am angry."

- "When you're old, you have to do more than you did when you were young."

- "Those who ask too much, who enjoy what is involved, are exposed to confusion."

- “Man has to persist in the belief that the incomprehensible is understandable; otherwise he would not do research. "

- "You don't have to travel around the world to understand that the sky is blue everywhere."

- "The wrong thing has the advantage that you can always gossip about it, the real thing must be used immediately, otherwise it won't be there."

- "You can't get rid of what belongs to you, and if you throw it away."

- "The exams increase over the years."

- "You are never cheated, you cheat on yourself."

- "Whoever praises someone, he equates."

- “It is not enough to know, one must also apply; it is not enough to want, one also has to do. "

- "Nothing is more harmful to a new truth than an old error."

- "The greatest difficulties lie where we don't look for them."

- "Don't be impatient if your arguments are not accepted."

Goethe about his work

“… They [the smaller stories] should all form a strangely attractive whole, tied together by a romantic thread under the title Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre . For this purpose there are notes: The end of the New Melusine, the man of fifty years, the pilgrim fool. "

"By the way, this work [Wilhelm Meister] is one of the most incalculable productions, to which I almost lack the key myself."

“I hope that my years of wandering are now in your hands and have given you a lot to think about; do not despise communicating anything. Ultimately, our life resembles the Sibylline books ; it becomes more and more precious, the less of it is left. "

“A work like this [the wandering years], which announces itself as collective, in that it seems to be undertaken only to combine the most disparate details, allows, yes, more than any other, that everyone appropriates what is appropriate to him, what is in called for his position to be taken to heart and might do harmony and charity. "

“But with such a booklet [the years of wandering] it is like life itself: in the complex of the whole there is what is necessary and accidental, superior and connected, sometimes successful, sometimes thwarted, whereby it maintains a kind of infinity that is contained in understandable and sensible words cannot be understood or included. But wherever I would like to direct the attention of my friends and also would like to see yours directed, are the different, separate details, which, especially in the present case, decide the value of the book. "

Features of the novel

type

Goethe himself describes this late work as a novel . It consists of three books as well as reflections in the sense of the hikers and materials from an archive.

The classification of the wandering years by experts changes over the years.

- In 1950, Erich Trunz simply defined the years of traveling as a framework narrative with inserted novellas.

- In 1968, Volker Neuhaus described the years of wandering as an “archive novel”, based on Makarien's archive and its content, among other things . Indeed, much of the novel is negotiated by letter. It's all about papers.

- Gero von Wilpert called the Wanderjahre a time novel . According to Wilpert, Brentano defined the time novel as an expanded social novel . In the Zeitroman, by definition, a picture of society, spirit, culture, politics and the economy of a time is painted on a circular horizon. In the case of the years of wandering , it is the picture of the time in which Goethe lived and which Goethe extrapolated into the 19th century by writing .

Representation

Gidion has written a book to illustrate the years of travel.

Goethe burdens the wanderer Wilhelm with two restrictions by letting him state:

- "I shouldn't stay under one roof for more than three days." (1,1)

- "Now no third party should become a constant companion to us on my wanderings." (1,3)

The resulting constant change of place and person also creates the disparate novel structure that Goethe pointed out on July 28, 1829 and which then led many recipients to thoughtless utterances.

Even more than in the apprenticeship years , Goethe demands a patient reader in the years of traveling . Jarno from the apprenticeship years is called Montan during the traveling years . Nachodine is hiding behind the “beautiful and good” and the “nut-brown girl”.

Time of action

At two places in the text the reader learns that the migration leads back to the 18th century. The wanderer Wilhelm Meister is once on the way to a castle in a gallery, "in which only portraits were hung or set up, all people who had worked in the eighteenth century" (1,6). And when the prehistory of the novel is told another time, it says: “The lively drive to America at the beginning of the eighteenth century was great” (1.7).

Motive of renunciation

Goethe has this central concept of his ethics, the renunciation of the lower in favor of the higher, in From my life. Poetry and truth are defined in (4.16): “Our physical as well as social life, customs, habits, sophistication, philosophy, religion, yes many a random event, everything calls to us that we should renounce ... This difficult task, however solve, nature has endowed man with abundant strength, activity and tenacity. "

Because Goethe even included the term in the title during the wandering years , it is discussed in detail in the secondary literature. Wilpert (anno 1998, p. 1189 below) counts z. For example, the novellas inserted in the novel are examples of stories about people who have not yet succeeded in renunciation.

Renunciation is the program for Goethe's novel concept . This can be seen from the details:

- (1,4) The "strange obligations of those who renounce" also include: "that they, when they come together, may speak neither of the past nor of the future , only the present should occupy them".

The joys of physical love between man and woman are usually renounced in favor of the highest values. Perfection is sought.

symbolism

Behind the ostensible plot are allegorical figures and symbols in the years of traveling .

For example, boxes and keys symbolize the secret of life. In addition, the symbol in Goethe is rarely clear. Quite a few Goethe interpreters understand boxes and keys - to stay with the example - in connection with the love story between Hersilie and Felix (3:17) also as sexual attributes.

The description of the novel's plot opens up many questions for interpretation. For a more detailed examination of the work, please refer to the extensive secondary literature .

reception

(Sorted by year of reception)

- 1830: The young Theodor Mundt (1808–1861): “We have to be honest, and, in order not to do the poet injustice, the years of wandering straight away, even in their current form for an unfinished fragment that is only more or less in individual parts appears less developed and completed, explain. "(Blessin, p. 374)

- 1895: Friedrich Spielhagen wants the “poetic” novel and asks “whether we are still dealing with poetry everywhere”. (Gidion, p. 11)

- 1918: Friedrich Gundolf : "The years of wandering are written by a wise man who can write poetry, not by a poet who is wise." (Gidion, p. 15)

- 1921 and 1932: Thomas Mann deals with the years of traveling .

- 1936: Hermann Broch affirms that Goethe laid " the foundation stone of the new poetry, the new novel" during the years of traveling . (Bahr, p. 363)

- 1963: Richard Friedenthal (p. 469 f.): “ After all, the years of wandering are no longer a novel, but a repository [= bookshelf, filing cabinet] for Goethe's wisdom of age ... He [the master complex] mocks all the rules. Goethe himself often scoffed at it ... "

- 1989: Hannelore Schlaffer cites works by in her habilitation thesis

- Ferdinand Gregorovius : Göthe's Wilhelm Meister developed in its socialist elements. Koenigsberg 1849

- Wilhelm Emrich : The problem of the interpretation of symbols with regard to Goethe's ›Wanderjahre‹. 1952

- Karl Schlechta : Goethe's Wilhelm Meister. Frankfurt am Main 1953

- Arthur Henkel : Renunciation. A study on Goethe's old age novel . Tübingen 1954

- Friedrich Ohly : To the small box in Goethe's "Wanderjahren". 1961

- Hans-Jürgen Bastian: The late Goethe's image of man. An interpretation of his story "Saint Joseph the Second". Weimar 1966

- Manfred Karnick: "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre" or the art of the indirect . Munich 1968

- Benno von Wiese : The man of fifty years . Düsseldorf 1968

- Marianne Jabs-Kriegsmann: Felix and Hersilie (in: Erich Trunz (Ed.): Studies on Goethe's old works ). Frankfurt am Main 1971

- Peter Horwath: On the naming of the "nut-brown girl" . 1972

- Anneliese Klingenberg: Goethe's novel "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre". Berlin 1972

- Wilhelm Vosskamp : Romantic theory in Germany. Stuttgart 1973

literature

source

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Poetic Works. Volume 7, Phaidon Verlag, Essen 1999, ISBN 3-89350-448-6 , pp. 387-717.

Secondary literature

(Sorted by year of publication)

- Richard Friedenthal : Goethe. His life and his time. R. Piper Verlag, Munich 1963, pp. 673-676.

- Heidi Gidion: On the representation of Goethe's 'Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre' . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Goettingen 1969.

- Adolf Muschg : "Formed to the point of being transparent". Epilogue to “Goethe Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre”. Insel Taschenbuch, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 3-458-32275-2 , pp. 495-523.

- Ehrhard Bahr in: Paul Michael Lützeler (Hrsg.), James E. McLeod (Hrsg.): Goethe's narrative. Interpretations. Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-15-008081-9 , pp. 363-395.

- Hannelore Schlaffer : Wilhelm Meister. The end of art and the return of myth . Metzler, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-476-00655-7 .

- Gerhard Schulz : The German literature between the French Revolution and the restoration. Part 2: The Age of the Napoleonic Wars and the Restoration: 1806–1830. Munich 1989, ISBN 3-406-09399-X , pp. 341-353.

- Stefan Blessin: Goethe's novels. Departure into the modern age . Paderborn 1996, ISBN 3-506-71902-5 , pp. 239-382, pp. 405-406.

- Gero von Wilpert : Goethe-Lexikon (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 407). Kröner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-520-40701-9 , pp. 1187-1191.

- Karl Otto Conrady : Goethe. Life and work. Düsseldorf / Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-538-06638-8 , pp. 983-1001.

- Manfred Engel : Modernization crisis and new ethics in Goethe's novel "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre or Die Renagenden" . In: Henning Kössler (Ed.): Value change and new subjectivity. Five lectures. Erlangen 2000, pp. 87-111. (Erlangen Research, Series A, Vol. 91)

- Gero von Wilpert: Subject dictionary of literature (= Kröner's pocket edition. Volume 231). 8th, improved and enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-520-23108-5 .

- Günter Saße : Emigration to the Modern Age. Tradition and innovation in Goethe's novel "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre" . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-022553-2 .

- Jochem Schäfer: Goethe and his late work "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre" in the light of the resistance against National Socialism: The German Hiking Day 1927 in Herborn and its consequences . Books on Demand , June 2011. ISBN 978-3-8423-4428-0

Audio books

- Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre, read out in full by Hans Jochim Schmidt, Reader Schmidt Hörbuchverlag, ISBN 978-3-941324-90-9 .

Web links

- Wilhelm Meister's wandering years in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The text at Zeno.org

- Wilhelm Meister's years of traveling. at Project Gutenberg : Volume 1 , Volume 2 , Volume 3

- Public domain audio book Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre by Goethe at LibriVox

- Literature Brevier : Wilhelm Meister's Wanderjahre by Goethe Selected passages from the novel "Wilhelm Meister's Wandjahre"

- Original drawing by Max Liebermann as a draft for the woodcut by Otto Bangemann, which was included in the special edition of the book.

- Hans-Jürgen Schatz: Reading by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe "The man of fifty years"

Remarks

- ↑ Wilpert, p. 1187, 3rd Zvu

- ↑ The chapter in the book is referred to with a pair of numbers in the form (book, chapter).

- ↑ Goethe advocated this theory, but he saw, like Montan, a constant cycle in the entire history of science: scientific treatises, mineralogy and geology . In: Complete Works , Cotta, vol. 33, p. 112.

- ↑ Frank Nager: The healing poet. Goethe and medicine. Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1990; 4th edition ibid 1992, ISBN 3-7608-1043-8 , pp. 205 f. ( Wilhelm Meister - a late caller ).

- ↑ Quote: “The editor of this sheet here” (2.8) assures us that we “have picked up a novel”. (1.10)

- ↑ Bahr, p. 379 below

- ↑ Bahr, p. 380.

- ↑ Wilpert, 1998, p. 1189 below

- ↑ Wilpert, 2001, p. 917.

- ^ Gidion, 1969.