Wanderer's Nightsong

Wanderer's night song is the title of two poems by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , which are among his most famous: Der du von dem Himmel bist from 1776 and Over all peaks from 1780. Goethe had the latter printed for the first time in 1815 in Volume I of his works . Both poems are on the same page, with the older Wanderer's Night Song and the younger Eines under the heading, which is to be understood as another Wanderer's Night Song . In this way the poems were also included in the Complete Edition of 1827. Is Above all summitsalone, meaningfully only Wandrer's Nachtlied comes into consideration as a heading .

Who are you from heaven (1776)

Goethe's handwriting of “Wanderer's Night Song” (Who you are from heaven) has survived between his letters to Charlotte von Stein . It is signed “Am Hang des Ettersberg , d. Feb. 12, 76 ".

You who are from heaven,

calm all joys and sorrows

, who are doubly miserable,

doubly fill with refreshment;

Oh, I'm tired of the hustle and bustle!

What is all this agony and lust for?

Sweet peace,

come, oh come in my chest!

For the edition of his works published by Göschen in 1789, Goethe changed the second and sixth verses by replacing "all joy and pain" with "all sorrow and pain" and "all the agony and pleasure" with "all the pain and pleasure", what seems unusual to some and not necessarily compliant with the rules

You who are from heaven,

calm all suffering and pain

, who is doubly miserable,

doubly fill with refreshment;

Oh, I'm tired of the hustle and bustle!

What's all the pain and pleasure for?

Sweet peace,

come, oh come in my chest!

It can be assumed that “Wanderer's Night Song” is not about some tired wanderer, but that Goethe also and above all speaks of himself here. There is nothing of this in his short note to Charlotte von Stein of February 12, 1776: “Here is a book for serious people, and Carolin. I feel that I will have to come myself, because I wanted to write a lot, and yet I feel that I have nothing to say other than what you already know. " How calmly and easily I slept, how happy I got up and saluted the beautiful sun for the first time in a fortnight with a free heart, and how full of thanks to you angel of heaven, to whom I owe it. ”In his autobiography From mine Life. Poetry and truth also tells Goethe how, after his separation from Friedrike Brion in August 1771, he was found "guilty for the first time" and in "a gloomy repentance", "reassurance [...] only in the open air" and how he was found for his Wandering [...] called the wanderer ". Of the strange hymns and dithyrambs that he sang on the way, "there is still one left, under the title" Wanderer's Storm Song ".

Hans-Jörg Knobloch even wants to understand Goethe's " letter poem " to Frau von Stein as an "attempt to seduce" those whom he adores. It was only the processing for the print, with which Goethe, as Herder wrote, was about "making the all too individual and momentary pieces edible", had made the reinterpretation into a prayer for peace possible. Such an interpretation is particularly suggested by the opening verse “You are from heaven”, an echo of Zinzendorf's song about The Lord's Prayer [sic] “You are in heaven” [sic] from the second edition of the so-called Ebersdorf hymn book that Goethe's father owned.

Above all peaks (1780)

Goethe probably wrote “Above all peaks” on the evening of September 6, 1780 in pencil on the wooden wall of the hunting guard's hut on the Kickelhahn near Ilmenau . There, “on the Gickelhahn, the highest mountain in the area”, “to avoid the urban desert, the complaints, the desires, the incorrigible confusion of the people”, Goethe reported Charlotte von Stein with a “d. 6th Sept. 80 ", and continued:" If only my thoughts from today were written down there are good things underneath. My best, I climbed into the Hermannstein cave, to the plaz where you were with me and kissed the S, which is still as fresh as it was drawn from yesterday, and kissed it again ”. The verses that he wrote on the wooden wall of the hut were not mentioned in any of his subsequent letters. However, Karl Ludwig von Knebel's entry in his diary of October 7, 1780 can be related to Goethe's inscription: “Morning beautiful. Moon. Goethe's verses. With the Duke on the Pürsch [...] The night on the Gickelhahn again ”. It is uncertain whether Goethe's inscription corresponded in every detail with the text he published in 1815:

Above all the peaks there

is peace,

In all the

peaks you

hardly feel a breath;

The birds are silent in the forest.

Just wait! Balde

will rest so do you.

Goethe's writing on the wooden wall has not survived. Two early copies (or transcripts) by Herder and Luise von Göchhausen have in verse 1: Over all fields and in verse 6: the birds . This is generally considered to be an authentic early or first draft. The handwriting on the wooden wall, photographed in 1869, also has birds and not birds , on the other hand already peaks in verse 1. However, this may only be with later renovations and overpaintings that Goethe himself or well-meaning visitors have made on the fading handwriting in the hut over the decades , an original climes have replaced.

The first publication, unauthorized by Goethe, in the last episode of a multi-part article Comments about Weimar by Joseph Rückert, which appeared anonymously in September 1800 in the journal Der Genius der Zeit published by August Adolph von Hennings in Altona , also has birds in verse 6, but Still further deviations from the version of 1815: “Above all the tops” (verse 1), “in all branches you hear no breath” (verses 3–5) and “you sleep too” (verse 8). The English version of the article in The Monthly Magazine (London) also published the poem in this form in February 1801, as did Kotzebue in his Berlin newspaper Der Freimüthige on May 20, 1803; with him, however , the birds had become birds .

On August 27, 1831, six months before his death, Goethe visited the Kickelhahn one last time during his last trip to Ilmenau. With the mining inspector Johann Christian Mahr , whom he said he had not visited the area for thirty years, he went up to the upper floor of the hunting lodge; In earlier times he had lived there with his servant for eight days and had written a little verse on the wall that he would like to see again. Mahr reports how he thought Goethe about the pencil writing with the date “D. September 7, 1780 Goethe "and continues:

- “Goethe read over these few verses, and tears flowed down his cheeks. Very slowly he took his snow-white handkerchief out of his dark brown kerchief, dried his tears and said in a gentle, melancholy tone: "Yes: just wait, soon you will rest too!" Was silent for half a minute, looked through the window again into the dark pine forest and then turned to me with the words: "Now we want to go again!" "

On September 4, 1831, Goethe wrote to Carl Friedrich Zelter from Weimar:

- “I was absent from Weimar for six days, the sunniest of the whole summer, and made my way to Ilmenau, where I had done a lot in earlier years and had a long break from seeing each other, on a lonely wooden house on the highest peak of the fir forests I recognized the inscription of September 7th, 1783 [sic!] of the song that you carried so lovely and calming all over the world on the wings of music: "Above all peaks there is peace pp." "

The inscription was meanwhile so damaged that Goethe either carried out a renewal himself or had it done by Oberforstmeister von Fritsch.

reception

The Goethe cult - also around the place of origin, which is recorded on hiking maps as "Goethehäuschen" as early as 1838 - corresponded to a veneration of the poem, which was seen as a celebration of universal calm. Franz Schubert , who admired Goethe very much and felt strongly inspired by him, set Der du von dem Himmel bist on July 5, 1815 as op. 4/3 ( D 224) and over all summits around 1823 as op. 96 No. 3 ( D 768). The mountain hut on the summit of Kickelhahn burned down in 1870 and was rebuilt in 1874. A photograph from 1869 documents Goethe's text in the state it was in immediately before its destruction. In addition to overpainting and scribbling, which had distorted the original over the course of 90 years, the photo also shows saw marks: a tourist tried in vain to cut the text out of the wall.

The following meanings have been assigned to this poem:

- an evening song that urges death;

- a nature poem;

- a poem about the position of man in the cosmos.

Speaks in favor of these interpretations

- the organization of its elements: the peaks (inanimate or inorganic); the tops and birds (animated or organic, but already calm); man (still restless, but already in anticipation of sleep and death);

- the sequence following the development of evolution: rock (summit) - plant (treetop) - animal (birds) - human (you);

- the zoom-like pan from the extreme distance (summit) over the nearer horizon (forest) into the innermost thoughts of the human being.

Accordingly, for the Goethe researcher Sigrid Damm, the little poem Above all summits is Ruh is also Goethe's “perhaps the most perfect novel about the universe ”, which he basically always planned but never realized: “The verses wander through in a single image and Thoughts that have become speech-sound throughout the cosmos.

After a translation conference on Goethe's 250th birthday in Erfurt in August 1999, three glass panels were installed in the hut in April 2000 showing the poem in the German original and 15 translations.

The poem was also used as the text for the piece of music "They'll Remember You" in the soundtrack to the film Operation Walküre - The Stauffenberg Assassination , composed by John Ottmann and Lior Rosner.

Parodies

With the extraordinary fame of Über allen Gipfel - similar to Schiller's Lied von der Glocke - parodies were inevitable.

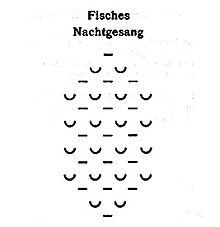

Fisch Nachtgesang from Christian Morgenstern's gallows songs , published in 1905 , by the fictional publisher of later editions Dr. Jeremias Mueller described in a note as “the deepest German poem”, consists “only of metric symbols”, which Martin Beheim-Schwarzbach “reminds of the opening and closing of a carp's mouth”.

The evening prayer of a negress with a cold from Joachim Ringelnatz 's volume of poems Kuttel Daddeldu from 1920 ends with the following lines:

Over by the forest

there is a guru - -

just wait for

kangaroos too soon.

In Karl Kraus ' tragedy The Last Days of Mankind about the First World War , a “Wanderer's battle song” is presented in the 13th scene of the second act, which replaces Goethe's last verses with these:

Hindenburg is sleeping in the forest,

just wait,

Warsaw will fall too.

Liturgy from the Breath of Bertolt Brecht's house postil from 1927 depicts the starvation of an old woman in six stanzas with a refrain that parodies Wandrer's night song; because "the bread that the military ate". Increasing protest: “A person should be able to eat, please”, is suppressed with increasing brutality first by a “commissioner” with a “rubber club” and then by the “military” with a “machine gun”. The refrain reverses Goethe's poem, after death has already been mentioned in every stanza, first the "birds" and then combines Goethe's summit, above which there is peace, and his treetops, in which you can hardly feel a breath :

Then the birds in the forest were silent.

There is peace above all the tops.

In all the peaks you can

hardly feel a breath.

In the seventh and last stanza, finally, “a big red bear comes along” (the October Revolution ) and “ate the birds in the forest”.

The birds were no longer silent.

There was a balance over all the tops.

In all the peaks you can

now feel a breath.

The following anecdote found some circulation since about 1965: “In 1902 Ein Gleiches was translated into Japanese, in 1911 it was translated from this language into French and shortly afterwards from French into German, where it was published as a Japanese poem under the title Japanese Night Song in a literary magazine was printed. "

There is silence in the jade pavilion.

Crows fly in silence.

To cherry trees covered in snow in the moonlight.

I sit

and cry.

A primary source, the so-called German "literary magazine", is never named. It is therefore likely to be a parodic mystification, which, like a modern legend , is now often taken at face value.

Georges Perec and Eugen Helmlé wrote a 47-minute radio play entitled The Machine (1968), produced for Saarland Radio . The attempt is made to “simulate the working of a computer that was given the task of systematically analyzing and breaking down Wandrer's Nachtlied by Johann Wolfgang Goethe.” Even before the actual computational linguistics , the radio play plays through their possible possibilities and parodies them with Goethe's poem potentially meaningless inexorability. At the same time, a multitude of supposedly computer-generated new parodies of Goethe's poem arise through omissions, rearrangements and reformulations.

In Daniel Kehlmann's novel Die Vermessung der Welt (2005), Alexander von Humboldt , in a boat on the Rio Negro , is asked by his companions

- also to tell something.

- He didn't know any stories, said Humboldt [...] But he could recite the most beautiful German poem, freely translated into Spanish. Above all the mountain peaks it was quiet, there was no wind in the trees, the birds were quiet too, and soon one would be dead.

- Everyone looked at him.

- Done, said Humboldt. [...]

- Sorry, said Julio. That couldn't have been all.

Walter Moers ' fantasy novel The City of Dreaming Books presents Goethe's poem as Der Nurnenwald by the Zamonian poet Ojahnn Golgo van Fontheweg , in which Goethe's " little birds" are replaced by "Nurnen", meter-high, bloodthirsty animals with eight legs that resemble trees therefore can hardly be seen in the forest.

The Austrian lyric poet Andreas Okopenko wrote his ironic version in 1983 under the title Sennenlied , in which he irritates the relationship between the lyrical self and nature with a disenchantment :

Above all the treetops,

the cow angrily eats

its butter croissants

and risks a horn.

(From: Andreas Okopenko: Lockergedichte , 1983)

In Asterix volume 28 "Asterix in the Orient" by Albert Uderzo, the doctor of Caesar, who has just recovered from the fever, says:

"Come with me into the fresh air! There is peace over seven hills, in all the breezes you can hardly feel a smoke."

Web links

- (283 KB, OGG)

- Goethezeitportal (postcards with the Goethe poem)

- Goethe hiking trail Ilmenau – Stützerbach

literature

- Sigrid Damm : Goethe's Last Journey , pages 129-143. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2007, ISBN 978-3-458-35000-2 .

- Sebastian Kiefer: Above all peaks: magic, material and feeling in Goethe's poem "Ein Gleiches". Thiele, Mainz 2011, ISBN 978-3-940884-51-0 .

- Hans-Jörg Knobloch: Wanderer's night song - a prayer? In: Hans-Jörg Knobloch, Helmut Koopmann (ed.): Goethe / New Views - New Insights . Publishing house Königshausen & Neumann 2007.

- Wulf Segebrecht : Goethe's poem over all peaks is calm and its consequences. Texts, materials, comments. Carl Hanser, 1978, ISBN 3-446-12499-3 .

- Uwe C. Steiner: Summit poetry. Wanderer's sorrows, ups and downs in Goethe's two night songs. In: Bernd Witte (ed.): Poems by Johann Wolfgang Goethe (interpretations). Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-15-017504-6 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Goethe’s works. First volume. Stuttgart and Tübingen, in the JG Cotta'schen Buchhandlung. 1815, p. 99 ( digitized in the Google book search); see also Goethe's works. First volume. Original edition. Vienna 1816, p. 111 ( digitized in the Google book search).

- ↑ a b Erich Trunz , in: Goethes Werke (Hamburg edition) Volume 1, 16th edition 1996, p. 555 ( limited preview in the Google book search)

- ↑ Erich Trunz, in: Goethes Werke (Hamburg edition) Volume 1, 16th edition 1996, page 554 f.

- ↑ a b Goethe Repertory February 12, 1776 facsimile .

- ↑ Harald Fricke ( Die Sprache der Literaturwissenschaft , CH Beck 1977, page 237) points out to explain why Goethe does not mean “All suffering and all pain” and “What is all the pain and all the pleasure?”, “On the the metric and rhyme-structural regularities underlying the poem ”. Hans-Jörg Knobloch, pp. 97 and 101 f. ( Limited preview in the Google book search) suggests the assumption that Goethe modified lines 2 and 6 to “unusual additions”, “to roughen them up to give them a certain patina to give, a naivety that should give the poem a folksong-like character and, in connection with the opening verse "You are from heaven", had to move it close to a prayer. "See also article discussion

- ↑ 3/401 at Zeno.org .

- ↑ 3/406 at Zeno.org .

- ^ Goethe Repertory February 23, 1776 facsimile .

- ↑ From my life. Poetry and truth . Third part. Twelfth book at Zeno.org ..

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Knobloch: Goethe. Königshausen & Neumann, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3426-8 , p. 99 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ [Nikolaus Ludwig Reichsgraf von Zinzendorf]: "The Lord's Prayer." In: Evangelisches Gesang-Buch, In a sufficient excerpt of the old, new and newest songs, dedicated to the common in Ebersdorf For public and special use. [Edited by Friedrich Christoph Steinhofer .] The second and enlarged edition. Ebersdorf [in Vogtland] . To be found in the Waysen house. 1745 , page 742. At a copy of the first edition of 1742 in the Bavarian State Library: the sides 737-744 of the second edition 1745 with the addition (878,914 signature Liturg 477 m.) "Zweyte adding" tailed, including the Lord's Prayer -Lied Zinzendorfs ( MDZ reader , digitized in the Google book search). This was not originally available in the first edition; their text part ended with an “encore” on pages 657–720 (call number: 1090317 Liturg. 1362, MDZ reader ).

- ↑ Goethe deals with the Ebersdorfer Gesangbuch in Confessions of a Beautiful Soul from 1795, p. 309 ( digitized in the Google book search), but also mentions it at the age of 19 in his letters of September 8, 1768 and January 17, 1769 to his Leipzig mentor Ernst Theodor Langer (1743–1820). Letters Volume 1I, texts, ed. Elke Richter & Georg Kurscheidt, Akademie Verlag Berlin 2008, p. 131, line 24 ( limited preview in Google book search) and p. 155, line 10 ( limited preview in Google book search). - Compare Reinhard Breymayer : Friedrich Christoph Steinhofer. A pietistic theologian between Oetinger , Zinzendorf and Goethe . […] Noûs-Verlag Thomas Leon Heck, Dußlingen 2012, pages 24–27. The resonance of Zinzendorf's song was only noticed and cited in research by Reinhard Breymayer since 1999. - On the book ownership of Goethe's father see Franz Götting: The library of Goethe's father . In: Nassauische Annalen 64 (1953), pages 23–69, here page 38. The publication date “1743” given there apparently stands for the correct “1745” of the second edition. - Compare also Lothar G. Seeger: “Goethe's Werther and Pietism”. In: Susquehanna University Studies , VIII, no. 2 (June 1968), pp. 30–49 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang, Briefe, 1780, 4/1012 at Zeno.org .

- ^ Wulf Segebrecht, page 26; Sigrid Damm page 136.

- ↑ freiburger-anthologie.ub.uni-freiburg.de

- ↑ The actual first print of Goethe's poem (PDF)

- ^ The Monthly Magazine. Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, 1801, p. 42 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ August von Kotzebue: Der Freimüthige or Berlinische Zeitung for educated, impartial readers. Sander, 1803, page 317 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ However, Goethe's diary notes on August 29, 1813: “With serums. and suite [d. H. Duke Karl August and his entourage] ridden out. Gickelhahn, Herrmannstein, Gabelbach. High loop, from 10 am to 3 am. " Wanderer's Night Song at Zeno.org ..

- ^ Johann Heinrich Christian Mahr: Goethe's last stay in Ilmenau. In: Weimarer Sonntagsblatt No. 29 of July 15 (1855), pp. 123 ff. Goethe, Johann Wolfgang: Talks, [To the talks], 1831 at Zeno.org .

- ↑ Goethe, Johann Wolfgang: Briefe, 1831, 49/45 at Zeno.org .

- ↑ Wulf Segebrecht, page 30.

- ↑ GoetheStadtMuseum. Permanent exhibition. VI Nature Poetry. In: ilmenau.de. Website of the city of Ilmenau, accessed on December 27, 2018.

- ↑ Julius Keßler: A German sanctuary and its downfall . In: The Gazebo . Issue 40, 1872, pp. 656–658 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ^ Sigrid Damm: Goethe's Last Journey , Frankfurt a. M. 2007, page 130.

- ^ Ilmenau - Wanderer's night song. In: ilmenau.de. August 21, 1999, accessed January 17, 2015 .

- ↑ They'll Remember You- From the Valkyrie soundtrack on YouTube , from December 25, 2008

- ↑ Fish night song

- ↑ ders., Christian Morgenstern, Rowohlts Monographien (1964) 1974, p. 70.

- ^ Evening prayer of a negress with a cold on Wikisource

- ↑ Karl Kraus : The last days of mankind - Chapter 4 in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ alternatively: 12 "Even the birds were silent in the forest" or 24 "And now the birds are silent in the forest"

- ↑ Dagmar Matten-Gohdes: Goethe is good - A reading book. Beltz and Gelberg, Weinheim / Basel 1982, 2006, p. 66 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ See also [1]

- ^ Georges Perec, Eugen Helmlé: Die Machine Reclam Stuttgart, 1972, new edition: Gollenstein Verlag, Blieskastel 2001, ISBN 3-933389-25-9 .

- ↑ Daniel Kehlmann: The measurement of the world. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005, p. 127 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Wiesmüller: Nature and Landscape in Austrian Poetry since 1945 . In: Régine Battiston-Zuliani (ed.): Function of nature and landscape in Austrian literature . Bern / Berlin / Oxford / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-03910-099-8 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ Albert Uderzo: Asterix in the Orient . Asterix tape 28 . Ehapa Verlag, Stuttgart 1987, p. 17 .