6th Symphony (Myaskovsky)

| 6th symphony | |

|---|---|

| subtitle | with final chorus ad libitum |

| key | E flat minor |

| opus | 23 |

| Sentence names |

|

| Total duration | approx. 65 minutes |

| Composed | 1921 to 1923, revised in 1947 |

| occupation |

Symphony orchestra ( 3333/6661 / Pk / Schl / Hrf / Cel / Str ), mixed choir ( SATB ) |

| premiere | On May 4, 1924 at the Moscow Bolshoi Theater under the direction of Nikolai S. Golovanov |

The Symphony in E flat minor Op. 23 is the sixth symphony by the composer Nikolai Jakowlewitsch Mjaskowski .

History of origin

After completing the fourth and fifth symphonies , Myaskovsky initially returned to work on the opera The Idiot ( Dostoyevsky ). In 1918, however, the political situation in Saint Petersburg had become too risky and when the government offices were relocated to Moscow, Myaskovsky also relocated in autumn. In the same year, Myaskovsky suffered personal blows of fate: first his father died and shortly afterwards Dr. Revidzew, who had been a close friend of Myaskovsky and had fought with him on the front.

In Moscow he first lived with the Derschanovsky couple before he could afford his own apartment in January 1919. According to J. Derschanowskaja, it was there after a visit by the painter Lopatinsky that the thought of a new symphony occurred to him for the first time. It was also Lopatinski who performed Mjaskowski's French revolutionary songs Carmagnole and Ça ira , which the composer later used in the symphony. During this time, the political and social situation in Russia was very tense and there was a lack of almost everything that Myaskovsky had directly felt: There was hardly enough paper and there was almost no musical culture in Moscow. Therefore, Myaskovsky tried to help build one and so in 1921 he became a composition teacher at the Moscow Conservatory , a position he would hold for the next 30 years and which earned him the reputation of an excellent teacher. In Moscow, Mjaskovsky was ultimately unable to finish the opera, and he devoted himself to a new project: his Sixth Symphony, which he began to compose in early 1921.

The first mention of the symphony dates back to 1914, when Mjaskowski made a note of plans for a “grandiose” symphony. This symphony should have the title " Cosmogony ", which is not the case for the later sixth symphony. It is unclear whether these are really plans for the sixth symphony, since the First World War forced a break in Myaskovsky's work. In the symphony, Myaskovsky no longer directly dealt with the experiences of the war, even if these had had a lasting impact on his personality and music. Rather, he devoted himself to processing the October Revolution and the suffering of the Russian people associated with it. By early 1921, the sketches of the symphony were largely ready, but Myaskovsky was not satisfied with his work and initially set the symphony aside to devote himself to revising the first symphony and sketches for a seventh symphony . At this point he received the news of another personal stroke of fate: his aunt Jelikonida Konstantinovna, who had practically replaced his mother after the untimely death of his mother, had died in the difficult days of the famine in Saint Petersburg. On the one hand, this news caused great consternation in Myaskovsky; on the other hand, he wrote on December 30, 1921, when he was staying in Saint Petersburg for the funeral: “At night, in the ice-cold apartment, the sound images for the middle movements came to me 6th symphony in mind ”.

Myaskovsky orchestrated the symphony in the summer of 1922 when he was in Klin with Pawel Lamm, a pianist and director of the music sector at the state publishing house, and his family . The director of Tchaikovsky - the museum had invited the musicians to this place where Tchaikovsky also his sixth symphony was composed. The Pathétique had heard Mjaskowski age of 13 for the first time, then in him the decision had matured, even to become a musician. Another influence on the work was the drama Les Aubes by Émile Verhaeren , which Myaskovsky had read in Moscow, as well as Myaskovsky's fascination with the subject of death, which is also reflected in the use of the dies irae .

With the use of the French revolutionary songs, Myaskovsky fulfilled a demand for mass songs that had been placed on contemporary musicians in the still young Soviet Union by both the party and the common people. Myaskovsky, however, did not share the radical attitude that one should forget and reject the legacy of the classics. Before the premiere, Mjaskowski joined the newly founded ASM (Association for Contemporary Music), the antithesis of the RAPM (Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians). This changed his attitude towards modern music and his own style. The first signs can already be seen in the sixth symphony, even if there are still clear influences of the Russian classics such as the use of motifs from Boris Godunov . In the period that followed, Mjaskowski's works became more and more atonal and “bulky” before he returned to the demands of Socialist Realism around 1932 .

analysis

The sixth symphony shows some innovations and unusual features. First of all, it is by far the largest and longest work by the composer and one of the most formidable works in Soviet symphonic music. The duration of the performance is unusually long at 65 minutes, which was quite a risk for Myaskovsky, since the people wanted short and simple works. Furthermore, Mjaskowski uses a choir in the finale, which was possible since Beethoven's Ninth Symphony , but was still unusual. Mjaskowski had previously only dealt with singing in his romances, the use of a choir was completely new to him. The key of E flat minor, which is traditionally used for particularly gloomy works, is also unusual and caused enormous difficulties, especially for the strings at the premiere. For this reason, among other things, Mjaskowski reworked the instrumentation and some passages after the performance. The themes used are also striking: Mjaskowski had already used the dies irae in the second piano sonata ; together with the death song “The soul has detached itself from the body” it forms a strong contrast to the French revolutionary songs. The symphony is also the one with which the composer has occupied himself the longest. This created what is perhaps the most personal of his works.

The overall structure is based on the classical structure of the symphony, even if the individual parts differ greatly in form. Mjaskowski swaps the positions of the scherzo and the slow movement, which is now in third position. This procedure was common in large-scale symphonies such as those by Mahler and Bruckner , the reasons for this being mainly in the build-up of tension. This can be seen particularly well in Mjaskowski's symphony, the whole work seems to point towards the finale, the Andante appassionato forms a final haven of calm . The last sentence is also thematically the most interesting, the preceding sentences assume motifs in several places .

The symphony does not officially follow a fixed program, as Mjaskowski had written for his symphonic poems, for example. He was probably concerned that a historical connection that was too clear would meet with rejection and censorship. Nevertheless, the symphony has many passages in which the composer had very precise ideas about a "plot". This is particularly evident in the first and fourth movements.

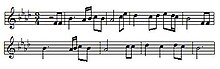

The first movement opens with six tutti - chords in fortissimo , which is a kind recitative represent. According to the author Malcom MacDonald, Myaskovsky came up with the idea for this introduction at a gathering at which Nikolai Krylenko shouted, “Death! Death to the enemies of the revolution! ”. This epigraph- like introduction is followed by an energetic sonata allegor . The main theme of this Allegro and the theme of the introduction run like a red thread through the entire piece. The Allegro consists of different ideas that can be divided into two thematic groups: a hectic group in E flat minor and a lyrical group in G minor . The first theme of the second group is reminiscent of passages from Mussorgsky's opera Khovanshchina , the second has strong romantic features. Overall, this second thematic group is one of the few moments of beauty, but the folk-song- like melodies performed by the horn and a solo violin are full of inner pain. The transitions of the exposition form strongly chromatic upsurges of the strings, which are very reminiscent of Scriabin , and fanfares of the winds. As in the earlier symphonies, this contrast of themes, reminiscent of images of battle, is reinforced in the development by newly added elements and skilful linking of the themes, whereby the first group of themes always seems to have the upper hand. In the coda the mood changes to E flat major and a strange mood arises that is completely alien to the previous character, but which is lost again in gloomy string tremolos . This sentence represents a struggle between the bitter reality of the (civil) war and the wishful thinking of the individual and also Mjaskowski himself.

The second movement is the Scherzo and is called Presto tenebroso , which literally translated means very fast and dark . This designation suggests the mood of the movement, the struggle of the first movement is continued here. The outer shape is ABA , whereby the A-parts are characterized by threatening, restless bass movements over which whipping dissonances can be heard. This mood is occasionally interrupted by a march-like theme, but overall this part retains the character that Pushkin had already created in his poem The Devil : an icy image that freezes the soul. The trio brings the Dies irae theme for the first time in the symphony , even if it is difficult to recognize at first. The violins played with mutes form a soundscape, above which the soft and somewhat spherical sounds of the celesta can be heard. The heavily modified theme of the Catholic funeral mass is a quote from Mussorgsky's Boris Godunow and represents the first clear motivational anticipation of the fourth movement. The repetition of the A section is more intense before it collapses and culminates in a stretto .

The third movement initially creates an extremely thoughtful mood. It begins with a slow, ponderous ascending line of bass, after which the clear main theme appears. This mood is interrupted in places by tutti chords and fanfares in the first movement. The Dies irae theme of the second movement appears twice , here in a somewhat accelerated variant. The tension seems to calm down again before the finale, even if the dies irae hangs over the sentence as a threat. The movement ends with a part in B flat major , which ends the struggle of the previous movements and promises peace. Which of the two topics won this battle remains open.

The fourth movement is the actual musical climax of the piece, to which all other movements aim. It begins with a completely surprising jubilation and joy with the two French revolutionary songs Carmagnole and Ça ira , which were still sung in Paris at the beginning of the 20th century. The Carmagnole is in E flat major, after which the Ça ira is first intoned in minor by the brass before it is played in B flat major in the whole orchestra. But the mood doesn't last long and the change to C minor and another version of Dies irae bring the gloomy reality back. After a few sighs from the orchestra, the clarinet plays a sad, devout theme: The song of the dead The soul has detached itself from the body (also separation of the soul from the body or From the separation of the soul from the body ) from the Russian Orthodox blessing . After a defensive unrest in the orchestra, the revolutionary songs are played again, but this time they seem forced, almost parodic . The initial mood can no longer be achieved and the topics end in lamenting cries, which the choir also joins for the first time. The nervousness slowly fades and the choir sings the song of the dead. The Latin text used comes from VI Sokolow and is:

| O, quid vidimus? | What did we see |

| Mirum prodigium, | Wonder of wonder |

| et portentum bonum, | Wonder of wonder |

| corpus mortuum. | a dead body. |

| Quod abs te, anima, | And like the soul |

| quod relinquebatur, | separated from the body, |

| quod relinquebatur, | separated |

| et deserebatur. | and said goodbye. |

| Tibi, anima, ad Dei | And like you, soul, |

| judicium est eundum, | must appear before God's judgment |

| o corpus | and you, body, |

| in humum humidum. | go to the damp mother earth. |

(Translation: Ulrike Patow; in some versions the Russian text is also used)

The prayer that is supposed to accompany the dead and ask for deliverance from all sins fades away and the theme of the Andante reappears . The symphony fades away with high notes in E flat major and only now has it finally found its peace. Overall, this work is to be understood as a reminder and remembrance: a reminder of the price at which the supposed victory was achieved and commemoration of the dead of the war and the revolution.

Reception and criticism

The Sixth Symphony was a great success from the start and is often referred to as Mjaskowski's "masterpiece". WM Beljajew, a musician friend of the composer, described the premiere in a letter as follows: “... The success of this symphony with the audience was downright overwhelming. For almost a quarter of an hour the audience tried in vain to call out the composer, who had withdrawn, until it finally reached its goal and Myaskovsky appeared. In total he had to go on stage seven times, where he was presented with a large laurel wreath. Some well-known musicians came to tears, and others declared that after Tchaikovsky's 6th Symphony, Myaskovsky's 6th symphony was the first truly worthy of such a name ... ”. Myaskovsky himself wrote to Prokofiev that the symphony had made a “shocking” impression and that it had “a certain inner persuasiveness and even an effective character [...] It is considered my best work ...”. However, the self-critical composer had also identified deficiencies and reworked this and the already completed Seventh Symphony based on the impressions of the performance. This work was completed shortly afterwards and the score could be printed.

Due to the lack of paper, the symphony was not published in Russia but in Vienna by Universal Verlag . The publisher then offered to print all of Myaskovsky's other works. It was not until 1948, after Mjaskowski's revision, that the work was published by the Musikalisches Staatsverlag (MUSGIS).

On January 24, 1926, Saradschew conducted a performance in Prague and on March 1 in Vienna. The concerts were very successful with the Czech and Austrian audiences. In November 1926 the American premiere took place under the direction of Leopold Stokowski . In Russia, however, the work was not heard for a long time, as it was accused of showing too little optimism in dealing with the October Revolution . The unspoken performance ban was only lifted with Stalin's death. Mjaskowski later rated the symphony negatively, he even talked about starting the count of his symphonies again with the seventh. Author Maya Pritsker, however, doubts this assessment is sincere; she considers a protective claim due to the political explosiveness of the symphony to be more likely. This is also supported by a later comment by Mjaskowski: "... The excitement that led to the creation of this symphony and the fever that gripped me while composing make this work still dear to me today."

Prokofiev's later 6th Symphony is also in E flat minor and has some other parallels to the work. So Prokofiev processed the Second World War musically like Myaskovsky did the civil war. Today the symphony is the only work by Myaskovsky besides the cello concerto that is regularly played. It is also the symphony of which most of the recordings exist, even if some recordings, such as the complete recording of Svetlanov , do not use a choir.

Historical classification

As already mentioned above, Myaskovsky deals with the experiences of the October Revolution in the symphony, but the question of his personal attitude remains open, also because the sources, which were shaped by Soviet propaganda, hardly allow an objective assessment. The fact that the work was subject to an unspoken performance ban under Stalin speaks in favor of a critical assessment of the events. Another argument is the arrangement of the themes in the last movement: The revolutionary songs appear first, before a mood of prayer and warning is created with the dies irae and the hymn of the dead. Another clue is that Myaskovsky deviated from his original plan of writing a symphony about the origins of life and instead dealt with the subject of death. Myaskovsky, on the other hand, was known to be conservative and traditional, and like many World War I soldiers, he displayed a high level of patriotism . Due to the direct experiences at the front and later in the civil war in Saint Petersburg, it is likely that Mjaskowski's view of things was a realistic and popular one and was therefore only in conflict with the glorification of the regime. It is known from Mjaskowski's diary entries that he later observed the Stalin era with “shame and horror”, but whether this was already foreseeable for him at that time cannot be answered.

Another question that arises is whether Myaskovsky deliberately wanted to provoke with the work. The use of a prayer a few years after the separation of religion and state in Russia was very daring and it was surprising that the work was allowed to be performed in this form at all. Due to the enthusiastic reception at the first performances and the fact that the composer had always tried in the course of his life to adapt his musical style to the respective specifications, he was probably able to "allow" himself this approach. Before the First World War he had written music in the tradition of Rimsky-Korsakov , Lyadow and Glasunow , and after the war he modernized his style and adapted it to the views of the ASM. From 1932, Myaskovsky adapted his style to the demands of socialist realism. Despite all his adaptations, his musical tightrope walk led to the fact that in 1948, along with Prokofiev and Shostakovich, he was one of the composers who were most heavily criticized in the so-called “formalism debate”. In contrast to the others mentioned, Myaskovsky made no public admission of guilt, which again underlines his position as an authority at the Conservatory and as the “musical conscience of Moscow”, which he had developed through works like this symphony.

literature

- CD supplement Warner Music France 2564 69689-8 (Miaskovsky: Intégrale des Symphonies, Evgeny Svetlanov (cond.))

- CD supplement WarnerClassics 2564 63431-2 (Myaskovsky: Symphonies 6 & 10, Dimitri Liss (cond.))

- Soja Gulinskaja: Nikolai Jakowlewitsch Mjaskowski. Moscow 1981. (German Berlin 1985)

Web links

- classicsonline.com

- universaledition.com

- sikorski.de

- kith.org

-

wanadoo.nl ( Memento from May 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- Alexandrei Ikonnikov: Miaskovsky's Symphonies: Symphony No. 6 ( Memento from June 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

-

myaskovsky.ru

- Maya Pritsker: Miaskovsky, Symphony No. 6, Op. 23