Berlin observatory

The Berlin observatory was an astronomical research facility that was founded in conjunction with the Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences and operated as the Royal Observatory of Berlin under the subsequent Royal Prussian Society or the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences .

From the original location of the old observatory in 1711 in the Berlin-Dorotheenstadt district , in today's Berlin-Mitte , it was relocated as the new Berlin observatory in 1835 to Berlin-Friedrichstadt in today's Berlin-Kreuzberg . A second move, from the still growing Berlin and also because of increasing light pollution , took place in 1913 to the Babelsberg Palace Park in today's Potsdam . As an indication of its origin, the facility was called the Berlin-Babelsberg observatory . After the Second World War , Berlin disappeared from the name. The Babelsberg Observatory was merged with the Potsdam Astrophysical Observatory and the Einstein Tower Solar Observatory to form the Central Institute for Astrophysics of the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin . After reunification, the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam was founded , the main location of which is now the Babelsberg observatory.

Important astronomers such as Johann Franz Encke , Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel and Johann Gottfried Galle worked at the formerly new Berlin observatory . In 1846 the planet Neptune was discovered from here .

story

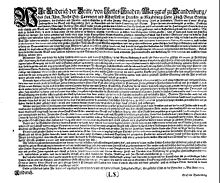

In September 1699 the Protestant imperial estates decided at the Perpetual Reichstag in Regensburg to introduce an "improved calendar" in the Protestant German states for the year 1700 in order to adapt the calendar calculation to the astronomical circumstances without the need for that of Pope Gregory XIII. Having to take over the Gregorian calendar decreed in 1582 , which, however, differed only marginally. It was not until 1775 that the evangelical imperial estates were persuaded to adopt the Gregorian calendar in full - with its Easter calculation - by Frederick II . The introduction of the improved calendar took place in February 1700 and followed the 18th of February of the Julian calendar with the 1st of March. In the course of this calendar reform , Friedrich III. , Elector of Brandenburg, issued a calendar patent on May 10, 1700 for the Berlin observatory, which is yet to be founded. Eight days later, Gottfried Kirch was appointed director or first astronomer ("astronomo ordinario") of the observatory. On July 11, 1700, on his 43rd birthday, the elector signed the foundation letter for an academy and an observatory for Berlin. With the Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences, the city got an academy like the ones London, Paris and Rome already had, based on plans by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and their support from Electress Sophie Charlotte . Leibniz became its first president. The fees for the calculation and distribution of the basic calendar by the astronomical facility served according to Leibniz 'concept - and based on an idea of the Jena university professor of mathematics, Erhard Weigel - as financial aid for the society and for a long time were almost the only source of income for the institution. Since the Society did not yet have its own observatory, Kirch carried out his observations from various private houses, including from 1705 at the private observatory of Privy Councilor Bernhard Friedrich von Krosigk in Wallstrasse in the Neu-Cölln district . Kirch's wife Maria Margaretha and son Christfried helped him with this. Maria Margaretha Kirch discovered, among other things, the comet of 1702. In 1701, the elector had been crowned the first king in Prussia. On January 1, 1710, the five previously independent cities of Dorotheenstadt, Friedrichstadt, Friedrichswerder and the twin cities of Berlin - Cölln , including Neu-Cölln am Wasser, were united to form the royal capital and residence of Berlin.

Old Berlin observatory

52 ° 31 '8 " N , 13 ° 23' 29" E

The first Berlin observatory was on the stables in Dorotheenstadt. The Marstall for 200 horses was built on Unter den Linden from 1687 to 1688 according to plans by the architect Johann Arnold Nering and a second floor was added from 1695 to 1697 for the Academy of Mahler, Sculpture and Architecture, founded in 1696 . From 1696 to 1700, Martin Grünberg expanded the building complex for the Societät der Wissenschaften, founded in 1700, to double its size to the north, as far as the last street, later Dorotheenstrasse (from 1822 to 1951 and since 1995 Dorotheenstrasse, with Clara-Zetkin-Strasse in between). From 1700 to 1711, a tower with three additional storeys was added to the north wing of the complex as the Grünberg observatory building. The 27 meter high building was one of the first tower observatories of the 18th century. In 1706 the observatory became partially usable and in 1709 it was more or less ready for occupancy. On January 15, 1711, the Royal Prussian Society of Sciences from 1701 held its first meeting in the tower and four days later, on January 19, 1711, its first festive meeting; on which the observatory was ceremonially handed over. It became the representative center of the society. Over time, their library and natural history cabinet were also housed in its rooms. The society was reorganized in 1744 by Frederick II into the Royal Academy of Sciences and was based there until 1752.

Gottfried Kirch died in 1710 a year before the academy and observatory opened. His assistant Johann Heinrich Hoffmann took his place as the head of the observatory . When Hoffmann died in 1716, Christfried Kirch was his successor - the son of Gottfried Kirch. His mother Maria Margaretha Kirch and his sister Christine Kirch supported him in creating the calendar , just as he once helped his father with his mother. When his mother died in 1720, the Society asked him to teach the astronomer Johann Georg Schütz, who was inexperienced in calendar making. Schütz helped him with practical activities from 1720 to 1736. After the death of Christfried Kirch, Johann Wilhelm Wagner took over the position of director in 1740 . The calendar calculation was largely continued for many years by Christine Kirch; she was also responsible for calculating the income. During the years of the "Old Observatory", Leonhard Euler , Joseph Louis Lagrange and Johann Heinrich Lambert , among others, dealt with astronomical issues in Berlin. 1765 Johann Castillon got the position of the first astronomer. In 1768 the observatory received a wall quadrant built by John Bird and thus the first important observation instrument. The measuring device can be viewed today in the Babelsberg observatory .

Long-term directors of the old observatory were Johann III Bernoulli from 1764 and after him from 1787 Johann Elert Bode . Lambert brought Bode to Berlin in 1773 to publish an astronomical yearbook with him ; after Lambert's death, Bode became the sole editor. The first volume of the Berlin Astronomical Yearbook for 1776 was published as early as 1774, opening the longest series of publications in astronomy that went up to 1959 . Thanks to this international documentation medium, the Berlin observatory developed into a news center of European standing. Bode was initially assigned to the aged Christine Kirch as an assistant with the calendar work. In 1774 he married a granddaughter of one of her sisters; she was also familiar with astronomy according to the Kirch family tradition. Christine Kirch died in 1782. As director of the observatory, Bode was able to benefit from the favor of Friedrich Wilhelm III. expand the facility with a second observation floor, which had previously been equipped with a third class. When Bode made a request on November 2, 1798, the observation rooms within the tower were limited to the third floor. The two floors above were combined into one spacious floor. The monitoring activities could be extended to these after the calculated costs of 4465 thalers and the plan had been approved on April 7, 1800 and the necessary renovation was completed in June of the following year. The construction work was led by Oberhofbaurat Friedrich Becherer and castle builder Bock.

In 1797 Johann Georg von Soldner came to Berlin as Bode's colleague and in 1801 Soldner's work on the severity of light appeared in the Astronomical Yearbook for 1804, with its inference about the curvature of light rays in a gravitational field. In 1805 Jabbo Oltmanns came to Bode in Berlin and helped him with his astronomical observations and work on the yearbook, in which his first own articles appeared. Oltmanns also became an employee of Alexander von Humboldt and processed the position data from his recently completed research trip through Central and South America; During this work, after Napoleon's occupation of Berlin in 1806 , Humboldt was summoned to Paris on a diplomatic assignment, and Oltmanns followed him in 1808. Until 1811, the astronomical institute was financed exclusively through the monopoly on calendar calculation, which the academy had been given when it was founded; In that year the academy lost its calendar privilege and was funded from the state budget and foundations in the future.

When a successor was sought for the management position of Bode for reasons of age, Carl Friedrich Gauß and Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel turned them down. On the recommendation of Bessel, Johann Franz Encke , director of the Gotha observatory since 1822 , was replaced by King Friedrich Wilhelm III. called to Berlin and appointed director of the Berlin observatory. Thanks to Alexander von Humboldt's influence, expensive equipment could be purchased and with his support, Encke also managed to build a new observatory on the outskirts of the city for the Prussian king. The condition was that the observatory was open to the public two evenings a week.

The new telescope and main instrument was a refractor from the Munich workshop of Joseph von Fraunhofer with an aperture of nine inches (24.4 cm) and a focal length of 4.33 meters. Humboldt applied for its purchase on October 9, 1828, including a meridian circle from the instrument maker Karl Pistor in Berlin and a chronometer from Friedrich Tiede's watchmaker's workshop in Berlin . He also requested the collection and submission of documents on the most appropriate construction of observatories. Thereupon approved Friedrich Wilhelm III. six days later 8500 thalers for the refractor, 3500 thalers for the meridian circle and 600 thalers for the chronometer. The refractor was Fraunhofer Fraunhofer’s last large telescope that still existed in Munich. At the same time, Humboldt received the power of attorney from the King for the requested collection of documents and their submission to the Ministry of Culture.

The Fraunhofer refractor arrived in Berlin on March 3, 1829. It is now in the Deutsches Museum in Munich . On April 7, 1829, five days before Humboldt set off on his expedition to Russia, the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel received the royal commission to design a new observatory and to submit these plans with the desired location. After his return, Humboldt wrote to builder Schinkel on May 1, 1830, asking for a draft. On August 10, 1830, the purchase of a building plot for the new observatory was approved.

The tower of the old observatory served between 1832 and 1849 as "telegraph station 1" from a total of up to 62 stations of the royal-Prussian optical telegraph connection from Berlin via Cologne to Coblenz . On July 3, 1903, the tower was demolished. The entire area of the former Marstall complex between Dorotheenstrasse and Unter den Linden has been occupied by the Berlin State Library since 1914 .

New Berlin observatory

52 ° 30 '12 " N , 13 ° 23' 35" E

The construction of the new Berlin observatory was carried out by the highest cabinet order of November 10, 1830 according to Schinkel's plans. At a price of 15,000 thalers, an approximately one-hectare plot of land near the Hallesches Tor was acquired, in the position of the acute-angled enclosure by Lindenstrasse and Friedrichstrasse in today's Berlin-Kreuzberg district . The foundation stone was laid on October 22, 1832, and in 1835 the observatory was completed on the current area between Encke-, Bessel- and Markgrafenstraße on Lindenstraße. The southern end of Charlottenstraße and forerunner of Enckestraße was later named Enckeplatz in honor of the director at the time, the observatory was given the address Enckeplatz 3 A (today Enckestraße 11).

The two-story building was a plastered building “in simple Hellenic styles ” as a combination of modernity and antiquity. The building was laid out in the shape of a cross with its longest arm facing east. At the intersection of the cross arms was the iron structure of a rotating dome with a diameter of 7.5 meters. It was the first observatory dome in Prussia in the shape of a hemisphere with a gap lock and rotating mechanism. The foundation of the actual observatory was independent of the rest of the building in order to avoid the transmission of vibrations. The library was under the dome. Further observation rooms and scientific work rooms were set up on the upper floor of the observatory. The long east wing housed the director's service apartment on the ground floor and was designed with a temple front, the main front in the gable relief showing the god of light Apollo with four horses. To the east of the building stood a small house with the castellan's official apartment .

The modern observation instruments included a nine-inch refractor from Fraunhofer and a pendulum clock from Friedrich Tiede. In 1838 the completed meridian circle by Karl Pistor was added.

On April 24, 1835, Encke was able to move into the new observatory with his newly hired employee, Johann Gottfried Galle . On May 19, the first observation took place in the building, which was only completed at the end of 1835. Galle had applied to Encke as an assistant well before it was ready to move into. In May of the same year Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel , who had been called from Königsberg, moved into the "Magnetic House" on the grounds of the observatory (see Freydanck's painting on the left) and during a three-month stay carried out pendulum observations for the creation of a new Prussian original length measure . In 1837 Encke discovered the division of Saturn's ring named after him with the Fraunhofer refractor , and Galle in 1838 discovered another dark ring near Saturn - the C-ring - and from 1839 to 1840 three new comets . On September 23, 1846, Galle and the astronomy student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest , assistant at the observatory since 1845, discovered the planet Neptune based on position calculations sent by the French Urbain Le Verrier . After initially unsuccessful, they were helped by the use of the “Berlin Academic Star Map” by Carl Bremiker, suggested by d'Arrest, which had just been printed . The letter from Le Verrier had reached Galle, who was on friendly terms with him, on the same day, coincidentally on the 55th birthday of Director Encke, who gave his permission to check the stated position of the sky ( see also: Neptune / Discovery ). At other observatories, the French astronomer's suggestion, based on deviations between the calculated and the observed orbit of the planet Uranus, to specifically identify another large planet that disrupts the orbit , was not regarded as promising enough. This was also the case at the Paris observatory , of which Le Verrier later became director. The Berlin observatory gained worldwide fame through the discovery of Neptune.

In addition, many calculations of the orbits of comets and asteroids were carried out on it. Galle was appointed director of the observatory in Breslau in 1851 . In 1852 Karl Christian Bruhns joined Encke as second assistant and became first assistant in 1854. In 1855 Wilhelm Foerster got a job as a second assistant. From 1857 Giovanni Schiaparelli studied at the facility for two years . When Bruhns moved to Leipzig in 1860 , Foerster was his successor as his first assistant. In the same year Foerster and his colleague Otto Lesser discovered the asteroid (62) Erato . After Encke fell ill, he became his deputy in 1863 and, in 1865, the year Encke died, director of the observatory. At that time the observatory was the most important astronomical research and teaching facility in Germany. In 1873 Viktor Knorre joined as an observer ; until 1887 he discovered the asteroids (158) Koronis , (215) Oenone , (238) Hypatia and (271) Penthesilea . From 1884 to the beginning of the 1890s, Karl Friedrich Küstner was also employed as an observer; During this time he discovered the polar movement based on his series of measurements . From 1866 to 1900 Arthur Auwers compiled his fundamental catalog in Berlin , a comprehensive star catalog with 170,000 stars.

On the north wing of the observatory, the height reference surface was mean sea level set for the Kingdom of Prussia. The marking was formally handed over on the 82nd birthday of Kaiser Wilhelm I on March 22, 1879. This 1879 normal high point was derived from the Amsterdam level and marked 37 meters above zero.

Wilhelm Foerster managed the observatory until his retirement in 1903. At his suggestion, the establishment of the Potsdam Astrophysical Observatory in 1874 for solar observation on the Telegrafenberg in Potsdam goes back to. The "Telegraph Station 4" formerly stood on the Telegrafenberg and gave it its name. In the same year, Foerster founded the Berlin Astronomical Computing Institute due to the constantly growing scope of the computation of the astronomical ephemeris , which is located in Lindenstrasse 91, on the premises and in connection with the observatory, as a "computing institute for the publication of the Berlin Astronomical Yearbook" moved into its own building. The majority of astronomers now worked in this theoretical part of the overall facility - in addition to the practical, observational part of the observatory itself. Under Foerster's supervision, the computing institute was headed by the “conductor” Friedrich Tietjen , who had worked at the observatory since 1861. He discovered the asteroid (86) Semele in 1865 . After Tietjen's death, Julius Bauschinger was appointed to Berlin as his successor in 1896 . He achieved full independence for the institute in the following year.

In 1912 it moved into a new building in Berlin-Lichterfelde . In 1944 it was subordinated to the Navy and relocated to Sermuth in Saxony to avoid bomb damage . After the Second World War , most of it was brought to Heidelberg in 1945 . Only the small remainder came back to the observatory that had moved to Potsdam-Babelsberg and was reintegrated into it in 1956.

Because Foerster was not a member of the Academy, the Royal Observatory was separated from the Academy in 1889 and attached to the Friedrich Wilhelm University . The original academy observatory has been used by the Berlin University since it was founded in 1809. In 1890, Friedrich Simon Archenhold became an employee of the observatory and, on behalf of Foerster, set up a photographic branch at Halensee in Grunewald for taking pictures of cosmic nebulae .

At the end of the 19th century, the rapid growth of the Berlin metropolitan area meant that the observatory, which was once newly built on the outskirts of the city, was completely surrounded and thus observational activities that met the demands of research were hardly possible. In the mid-1890s, Wilhelm Foerster, among others, suggested building a new observatory outside the metropolitan area.

In 1904 Hermann von Struve accepted the office of director as Foerster's successor. Under his leadership, the research facility expanded significantly and the project of a second move took shape. After trial observations in the surrounding area from June 1906 by Paul Guthnick , who, after completing his training as an astronomer, worked as an assistant at the Berlin observatory from 1901 to 1903 and as an observer since his return in 1906, the Ministry of Culture decided in favor of the proposed location in the palace gardens Babelsberg near Potsdam .

The abandoned location on Lindenstrasse is managed by the International Astronomical Union under the observatory code 548. Before the building was demolished, the normal high point from 1879 was replaced by the normal high point from 1912 , which was laid underground outside Berlin near Hoppegarten , a current district of Müncheberg .

Some of the last existing observation devices went to the successor facility: a new 30 cm refractor from Zeiss - Repsold , a meridian circle from Pistor & Martins from 1868 with 19 cm aperture and 2.6 m focal length, a six inch refractor from Georg Merz and a 4½-inch refractor from Merz & Mahler. After the building was demolished, the cleared area of the observatory was partially used after 1912 for the construction of a new street, which from 1927 was called Enckestrasse. Newly cut plots along the street were built on from 1913, including the Kreuzberg flower wholesale market (1922).

In 2012, a memorial stele was unveiled on the 100th birthday of the German Main Elevation Network at the exact location of the normal height point from 1879.

Berlin-Babelsberg observatory

52 ° 24 '18 " N , 13 ° 6' 15.1" E

In 1913, the Royal Observatory was finally relocated again after 78 years. The observatory in Berlin was cleared after the move and demolished in August 1913. The sale of the property covered the cost of erecting new buildings in the amount of 1.1 million gold marks and the purchase of new instruments in the amount of 450,000 gold marks. The property on the Babelsberg in the castle park was free for the royal institution. The mountain that gives its name to its surroundings is located around three kilometers northeast of the Telegrafenberg.

The main building was constructed from 1911 to 1913 according to a design by Thür und Brüstlein by Mertins, W. Eggert, Wilhelm Beringer and E. Wagner. The move was carried out by the precision engineering company Otto Toepfer & Sohn , which also made an astrograph and a straight-through instrument.

The first of the new instruments arrived in the spring of 1914. The following year, the installation of a 65 cm refractor was completed; it was the first large astronomical instrument from the Carl Zeiss company in Jena. In 1924 a 120 cm reflector telescope was completed , which at the time was the second largest telescope in the world and the largest in Europe. After the Second World War, the reflector telescope was dismantled and, like other observation instruments, went to the Soviet Union as a reparation payment . It was brought to the Crimea along with the dome of its own smaller building - for the reconstruction of the war-torn Crimean observatory in Simejis - where it is supposed to be in service today. In 2002 the remaining torso of the building was completed again and got a new dome; Since then, it has housed the library of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam .

Struve remained director of the observatory until his death in 1920 - until 1918 it was still called the Royal Observatory in Berlin-Babelsberg (or Berlin-Neubabelsberg) and from 1918 to 1946 it was called the University Observatory in Berlin-Babelsberg . After Hermann Struve, Paul Guthnick was appointed head of the observatory in 1921 and he remained its director for many years until 1946. In addition to this activity, the focus of his work was the photoelectric photometry of stars and the research of variable stars with a new photometer .

The new location in the original castle park belonged to the community of Neubabelsberg . The designation used, "Berlin-Neubabelsberg Observatory" should indicate that it is the Berlin observatory at the new location. The villa settlement Neubabelsberg was combined with the city of Nowawes to form the city of Babelsberg in 1938 . In 1939 this was then immediately incorporated into Potsdam. The observatory retained the name “Berlin-Babelsberg” for a number of years. Only after 1945 was Berlin no longer used in the name. Her IAU code is 536.

With the nationalization of the Sonneberg observatory , the Berlin-Babelsberg University Observatory was given a branch in the state of Thuringia as a new department .

Directors and other employees

| The directors of the Berlin observatory | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 1700–1710 Gottfried Kirch (1639–1710) |

9. | 1756–1758 Johann Jakob Huber (1733–1798) |

| 2. | 1710–1716 Johann Heinrich Hoffmann (1669–1716) |

10. | 1758 Johann Albert Euler (1734–1800) |

| 3. | 1716–1740 Christfried Kirch (1694–1740) |

11. | 1764–1787 Johann III Bernoulli (1744–1807) |

| 4th | 1740–1745 Johann Wilhelm Wagner (1681–1745) |

12th | 1787–1825 Johann Elert Bode (1747–1826) |

| 5. | 1745–1749 Augustin Nathanael Grischow (1726–1760) |

13. | 1825–1863 Johann Franz Encke (1791–1865) |

| 6th | 1752 Joseph Jérôme Le Francais de Lalande (1732–1807) |

14th | 1865–1903 Wilhelm Julius Foerster (1832–1921) |

| 7th | 1754 Johann Kies (1713–1781) |

15th | 1904–1920 Karl Hermann von Struve (1854–1920) |

| 8th. | 1755 Franz Ulrich Theodor Aepinus (1724–1802) |

16. | 1921–1946 Paul Guthnick (1879–1947) |

Other astronomical workers were, for example, Johann Friedrich Pfaff at the old observatory, and at the new one, for example, Johann Heinrich von Mädler , Gustav Spörer , Franz Friedrich Ernst Brünnow , Robert Luther , Friedrich August Theodor Winnecke , Ernst Becker , Wilhelm Oswald Lohse , Adolf Marcuse , Eugen Goldstein , Erwin Freundlich , Fritz Hinderer and Georg von Struve .

Other Berlin observatories

Urania , which was founded in 1888 and whose Bamberg refractor was relocated from Invalidenstrasse in Berlin-Mitte to the first location of the Wilhelm Foerster observatory in Papestrasse in Berlin-Schöneberg after its building was destroyed in World War II , was primarily intended for the public . In addition to this people's observatory , which has been on the Insulaner since 1963 , there are two more in Berlin: the Archenhold observatory , housed in Berlin-Treptow since the trade exhibition in 1896, and the Bruno H. Bürgel observatory , since 1982 in Berlin-Spandau.

literature

- GWE Beekman: The History of the Berlin Observatory . In: Sterne und Weltraum , 1988, 27, 11, pp. 642-647, bibcode : 1988S & W .... 27..642B

- Wilhelm Eggert: The new building of the Berlin observatory on the Babelsberg . In: Journal of Construction . Vol. 64 (1914), No. 10, urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-91940 , pp. 645-674. (With additional images on pages 54 to 59 in the atlas of the 1914 year, urn : nbn: de: kobv: 109-opus-91974 .)

Web links

- Literature from and about the Berlin observatory in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Images of the new Berlin Observatory in the collection Architectural designs (English)

- A short history of Berlin astronomy ... (also in English )

- Photos from the new Berlin observatory by Schinkel

- Academy Observatory . In: District lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

Individual evidence

- ↑ The calendar patent. Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, accessed on June 19, 2016 (text of the calendar patent).

- ↑ a b c Roland Wielen (ARI): The calendar patent from May 10, 1700 and the history of the Astronomical Computing Institute. (No longer available online.) 2000, archived from the original on July 20, 2007 ; Retrieved on June 19, 2016 (address at the ceremony on May 10, 2000).

- ^ Anne Brüning: From Lindenstrasse to Babelsberg . In: Berliner Zeitung , June 16, 2010.

- ↑ Topic 3. The foundation of the Brandenburgische Societät - the later Prussian Academy of Sciences - and the first Berlin observatory. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 10, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ^ Dorotheenstrasse. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

- ^ Academy of Sciences In: District dictionary of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ^ Hans Christian Förster: The first observatory in Berlin. TUB news portal, February 9, 2009, accessed November 24, 2009 .

- ↑ a b Monika Mommertz: shadow economy of science . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF)

- ↑ Berlin history from 1700 to 1799 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at gerd-albrecht.de

- ↑ a b Station 1: Berlin-Mitte Old Observatory optischertelegraph4.de

- ↑ Sebastian Kühn: Knowledge, Work, Friendship. Economics and social relations at the academies in London, Paris and Berlin around 1700. V&R unipress, 1st edition 2011, p. 121, ISBN 978-3-89971-836-2

- ↑ Topic 4. The first years of the observatory and the achievements of the Kirch family of astronomers. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 13, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ↑ Topic 5. The rise of science under Frederick the Great (1712–1786). (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 18, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ^ Wolfgang Kokott: Bode's Astronomical Yearbook as an international archive journal. Retrieved January 1, 2009 .

- ↑ Friedhelm Schwemin: The Berlin astronomer. Life and work of Johann Elert Bode (1747–1826) . In: Wolfgang R. Dick, Jürgen Hamel (eds.): Acta Historica Astronomiae . 1st edition. Vol. 30. Verlag Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-8171-1796-5 , p. 23 and 136 .

- ^ F. Schwemin: The Berlin astronomer . S. 51 ( see above ).

- ↑ Topic 6. Johann Georg Soldner and the curvature of light rays. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 20, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ^ Johann Franz Encke. Retrieved January 7, 2009 . friedensblitz.de

- ^ Encke, Johann Franz. Retrieved January 7, 2009 . knerger.de

- ↑ a b Kurt-R. Biermann: Miscellanea Humboldtiana . Akademie-Verlag, 1990, ISBN 3-05-000791-5 , ISSN 0232-1556 , p. 127–128 ( books.google.de [accessed December 4, 2009]).

- ↑ Alexander von Humboldt Chronology ( Memento from January 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ The refractor from Joseph von Fraunhofer Deutsches Museum

- ↑ Berlin in 1830 . In: Calendar of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ^ F. Schwemin: The Berlin astronomer . S. 96 ( see above ).

- ↑ a b Akademie-Sternwarte in the district lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ↑ Topic 7. The construction of the new Berlin observatory and the work of Johann Franz Encke and Alexander von Humboldt. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 14, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ↑ Berlin in 1835 . In: Calendar of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ^ Johann Gottfried Galle (1812-1910) . ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ^ JA Repsold: Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel . In: Astronomische Nachrichten , 1920, bibcode : 1920AN .... 210..161R (full text available)

- ^ Christian Pinter: Parisian sky mechanic . ( Memento of March 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ J. Bauschinger: Wilhelm Foerster † . In: Astronomische Nachrichten , No. 5088 bibcode : 1921AN .... 212..489B

- ↑ Bertram Winde : How the Berliners looked into the tube . Review of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein on: Dieter B. Herrmann, Karl-Friedrich Hoffmann (ed.): The history of astronomy in Berlin .

- ^ Walter Major: Facsimile print for the normal high point at the royal observatory in Berlin. (PDF; 103 kB) 2006, accessed April 30, 2010 .

- ^ ARI: Separation of the Astronomical Computing Institute from the Berlin observatory. Astronomical Computing Institute, accessed on June 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Topic 12. The Astronomical Computing Institute. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved January 17, 2009 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Gallery of the Universe

- ↑ On the history of the Astronomical Computing Institute. Astronomical Computing Institute, accessed on June 17, 2016 .

- ^ Marita Baumgarten: Professors and Universities in the 19th Century (= Critical Studies in History ) Volume 121

- ^ On the election of Alexander von Humboldt to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin 200 years ago HiN

- ↑ House with "sky cannon". (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 28, 2009 ; Retrieved April 24, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. nordkurier.de

- ↑ meeting. Struve, Hermann, The new Berlin observatory in Babelsberg. Retrieved June 1, 2009 . springerlink.com

- ↑ For the 100th birthday of the German main height network: Memorial to the memory of the former Prussian main high point in 1879 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Eggert: The new building of the Berlin observatory . In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung . 43, 34th year. Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin May 30, 1914, p. 318-321 ( kobv.de ).

- ↑ a b History of Potsdam Astrophysics. In: AIP. Retrieved September 7, 2019 .

- ↑ 1900-1920. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 10, 2012 ; Retrieved April 22, 2009 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. potsdam-chronik.de

- ^ Brief History. (No longer available online.) Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, archived from the original on July 16, 2011 ; accessed on August 14, 2010 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Jürgen Tietz: New in Potsdam. Library. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on August 16, 2010 ; Retrieved August 14, 2010 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Institute: Portraits AIP

- ^ H. Schmidt: Prof. Dr. Paul Guthnick - a pioneer of photoelectric photometry . (PDF; 162 kB)

- ↑ 300 years of astronomy in Berlin and Potsdam; Preface on astro.uni-bonn.de

- ^ Department of Sonneberg of the Berlin-Babelsberg University Observatory. Retrieved April 26, 2009 . 4pisysteme.de

- ↑ Directors of the Astronomical Computing Institute (until 1874 of the Berlin observatory) ZAH