Socially determined inequality of health opportunities

The concept of socially determined inequality of health opportunities describes the connection between social and health factors. These can be stratified horizontally and vertically, that is, social inequality in health can be demonstrated for similarly classifying differences such as age or gender, but also for subordinate differences such as poverty , lack of education or for professional status. As a consequence, there is a statistical increase in the risk of illness among socially disadvantaged people. This inequality is empirically examined by medical sociology and in research on social inequality .

There are different theories about this:

- 1. Causality hypothesis: Poverty makes you sick: This can manifest itself directly (malnutrition or malnutrition) or indirectly ( gratification crisis ).

- 2. Selection or drift hypothesis: Illness makes you poor: Conversely, it is possible that sick people are more difficult to integrate into working life.

- 3. Poverty or illness are both caused by a third factor.

Social inequality of health opportunities worldwide

Poverty often has consequences for the state of health .

At international conferences, the term “Health Inequality” has become established to denote health inequalities between different population groups. The World Health Organization publishes information on issues related to health inequality. The connection between social inequality and health is also the subject of the World Health Report.

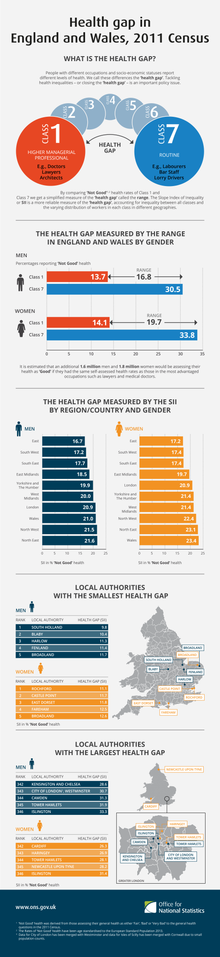

In Canada , the issue of social inequality in health opportunities received general attention through the LaLonde Report . In Great Britain , the 1980 Black Report documented inequalities.

Difference between poor and rich countries

There are big differences between poor and rich countries. Life expectancy in developing countries is usually shorter than in developed countries. In some parts of Africa, life expectancy has even fallen below 33 years. In Zambia, for example, the average life expectancy is only 32.4 years. For comparison: In Norway, on the other hand, it is 78.9 years. One of the reasons for this is the AIDS epidemic. In Zambia, 16.5 percent of the population is infected with HIV, in Zimbabwe even 25 percent. Poverty is seen as one of the reasons for the AIDS pandemic.

Poverty in developing countries leads to poor health care and poor nutrition. This in turn has a detrimental effect on mental, motor and social-emotional development. The affected children are less productive, have a poorer income later and are less able to look after their own children: a vicious circle. Worldwide, 219 million children under the age of five are cognitively impaired by poverty. That is 39 percent of all children in this age group in developing countries. In Africa it is as much as 61%.

The infant mortality rate is greatly increased in poor countries. Differences can be found not only between developing and industrialized countries, but also between rich and poor industrialized countries.

Social inequality of health opportunities in the United States

In the United States , the health disparities among minorities such as African Americans , Native Americans , Asian Americans, Latinos , and whites are well documented. When comparing these minority groups with the white population, there is an increased incidence of chronic illnesses, higher mortality rates and poorer health opportunities. Among the disease-specific ethnic inequalities in the United States, for example, is the 10% increase in cancer incidence rate among African Americans compared to whites. In addition, adult Latinos and African Americans are approximately two times more likely than whites to develop diabetes mellitus . Cardiovascular disease rates, chances of developing HIV / AIDS, and infant mortality are also higher than those of whites.

Areas in which there is no access to fresh food are called food deserts in the USA . The way to the next supermarket or discounter is much longer there than to the next fast food restaurant. In this context, it is considered problematic that in the US, according to a study by the US Department of Agriculture, 23.5 million people, one tenth of them without a car, live in areas with an extremely low average income and drive a mile or more to the nearest supermarket have to.

Researchers at Pennsylvania State University took blood samples from 9-year-old boys that their social milieu was reflected in the length of the telomeres . Disadvantaged children who suffer from chronic stress have shorter telomeres than socially better off. The influence of chronic stress on the accelerated shortening of the telomeres is assumed in the household of dopamine and serotonin .

Psychosocial Health

Low social status is a risk factor for mental illness. This applies, among other things, to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Even the probability of ever experiencing a traumatizing situation reveals social inequalities ( odds ratio 3.2: 1 for high school dropouts: college graduates). After the experience, differences in trauma processing can be seen. The lower the level of education, the more likely it is that the full picture of PTSD will develop and the more likely it is that there are comorbid disorders such as alcohol or substance abuse. The National Vietnam Veterans' Readjustment Study provided important insights into risk and protective factors for the development of PTSD in Vietnam War veterans . A high socio-economic status and a college education were among the protective factors.

Social inequality of health opportunities in Poland

In Poland, poverty leads to poor nutrition for those affected:

- In order to save money, meals are prepared of inferior quality - milk strongly diluted with water, pasta, pancakes, potatoes, cabbage, bread with lard .

Tarkowska was able to observe that the needs of the children in families - as long as they are not pathological - are in the foreground, but they are often malnourished and susceptible to infections.

In the event of illness, families are often unable to pay for the medication.

The living conditions are characterized by a lack of space. This is increased in winter, because poor families often only use parts of the apartment in winter to save heating costs. To save water costs, poor families bathe only once a week and several children are washed in the same water. Two, three or more people sleep in one bed. In Tarkowska's investigations, a woman shared a bed with four of her youngest children. This contributes to the spread of infectious diseases. In the north of Poland, tuberculosis is on the rise and is increasingly affecting socially disadvantaged groups. In order to fight tuberculosis, free advice centers have now been set up.

Social inequality of health opportunities in Germany

According to HG Schlack, poverty is one of the main risk factors for physical, mental and spiritual health in Germany. The unequal health opportunities due to poverty and wealth are increasing in Germany:

- “The socially determined differences in health have increased over the past 20 years. An example: More women and men from the lowest income group today rate their state of health as 'less good' or 'bad'. An opposite trend can be seen for women and men who earn very well. Poverty also has a direct impact on life expectancy. The median life expectancy of men in the lowest income group at birth is almost 11 years lower than that of men in the high income group. For women, the difference is eight years. "

According to observations by the Robert Koch Institute , there were connections between social class and health opportunities in the following areas:

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolemia

- Overweight and obesity

- Tobacco and alcohol use

- Physical activity and sports

- Drug use

- Subjective health and life satisfaction

- Health- related quality of life

- Utilization of the pension system

Research has found that people living in poverty are more likely to be overweight, smoke more often , and exercise less. The result is increased cardiovascular diseases. Winkler and Stolzenberg were able to show that the poor were more often affected by lung cancer, high blood pressure, heart attacks, circulatory disorders in the brain, circulatory disorders in the legs, type II diabetes, disc damage and hepatitis than non-arms.

Child and Adolescent Health and Poverty

The child poverty is increasing rapidly in Germany. In this area, the interlinking of poverty and health is important because it restricts the children's opportunities for a “good life”. Before they start school, children from poor families are increasingly diagnosed with developmental delays and health disorders. Psychiatric illnesses in childhood are more common among them. There are delays in language development and delays in intellectual and psychomotor development. They are also more likely to be affected by accidental injuries and dental problems.

In a brochure from the Robert Koch Institute on the subject it says:

- In addition to poorer starting chances at school and at work, an often poorer state of health and unfavorable health behavior patterns come into play. At the same time, recent social psychological research shows that the results of the socialization process are influenced by a large number of socio-economic factors.

In adolescence, a connection can be established between social situation, psychosocial well-being, the occurrence of pain and health behavior. According to Strohmeier , 80% of young people in the middle-class quarters of Bochum are healthy. In the satellite districts it is only 10 to 15 percent. The main diseases that go hand in hand with child poverty are obesity and motor disorders.

Unemployment and health

Unemployed

The special physiological and psychological stresses that people without work are exposed to result not only from the associated risk of poverty , but also from the subtle violations of human dignity that the unemployed feel every day. The Robert Koch Institute found that unemployed people have a less favorable state of health than those who work :

- The likelihood of assessing one's own health as less good or bad increases with the length of unemployment. Men who have been unemployed for one or more years are up to four times more likely to report poor or poor health than working men with no signs of unemployment.

Health-conscious behavior is also less pronounced, although a gender-specific difference can be seen here, as the example of smoking illustrates:

- While 49% of the unemployed men surveyed in the 1998 Federal Health Survey smoke, it is 34% of the employed male respondents. The differences among women are smaller with 31% smokers among unemployed women and 28% smokers among working women.

The evaluation of current health insurance data shows:

- Unemployed men spend more than twice as many days in hospital as working men.

- Unemployed women spend 1.7 times as many days in hospital as working women.

- The mortality increases as a function of the preceding unemployment duration continuously.

- Evidence has been found that unemployment is causal in the development of serious diseases.

Children of unemployed parents

Children of unemployed parents often react with discouragement and resignation, deterioration in concentration, behavioral problems and emotional instability.

Single Parent Health

| Burdens on single parents and married mothers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stresses / worries | single mothers | married mothers |

| Uncertainty about how your own future will continue | 48.8% | 26.4% |

| financial problems | 47.7% | 18.7% |

| Education and training of children | 34.5% | 27.1% |

| too many family responsibilities | 23.8% | 13.0% |

| Not being able to cope with the demands | 22.7% | 11.4% |

| not enough success | 20.3% | 7.5% |

| lack of harmony in the family | 17.9% | 4.1% |

| Problems with the housing situation | 16.6% | 6.2% |

| Feeling superfluous | 15.5% | 8.9% |

| Robert Koch Institute / Federal Statistical Office: Federal Health Reporting, Issue 14: Health of Single Mothers and Fathers | ||

Single parents without a partner are considered burdened. Single mothers are not only financial problems but also by future fears , signs of overwork and a lower self-esteem more heavily than married mothers (see table opposite the Robert Koch Institute).

Single mothers suffered or suffer from it significantly more often

- Kidney and liver diseases,

- chronic bronchitis and

- Migraine.

It is particularly noticeable that with 24.7% they report mental illnesses more than twice as often as the married mothers. In addition, they suffer more and more from pain than married mothers, which means that they are more likely to feel more impaired in coping with everyday life. Especially in the lower social class, single mothers feel more affected by pain and emotional problems than married mothers. The Robert Koch Institute assumes that "here the negative effects of single parenting on individual aspects of health-related quality of life are increased by belonging to the lower social class."

Single parents and married mothers make approximately the same number of doctor's appointments and cures. However, single mothers take fewer preventive medical checkups than married mothers. The doctor's appointments are also taken more often because of acute complaints than because of advice.

For Switzerland, Canton Zurich, the report “Health of Mothers and Children Under Seven” by the Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine of the University of Zurich showed that single mothers, but also mothers of more than two children, are particularly strong health endangered. This risk is mostly associated with a combined burden in the family, at work (mostly part-time work) and in the household.

Health inequality and migration

Social epidemiological research repeatedly points out that a particular burden on migrants and their descendants in the second and third generation can be demonstrated.

In particular, children with a migrant background have an increased infant mortality rate and an increased risk of accidents in later childhood.

Most of the people who have fled civil wars or torture have experienced trauma . Refugees sometimes wait a long time for psychotherapeutic treatment ( see BAfF ), and their psychotherapeutic care is considered inadequate in Germany.

According to the result of an evaluation of data from the Epidemiological Addiction Survey (ESA) from 2012 with around 9,000 respondents, alcohol consumption in Germany (as of 2012) is less widespread among people with a migration background from all groups of origin outside Europe and some groups of origin within Europe than among people without a migration background . If one only considers alcohol consumers (with and without a migration background), these persons do not differ significantly in their alcohol consumption.

Dark-skinned children and adults who live in northern countries, as well as people who keep their skin covered for cultural reasons, are among the risk groups for vitamin D deficiency .

Children with a migration background are more likely to be overweight than German children.

Many refugees suffer from conditions that endanger their health and life. Extreme lead poisoning occurred in the refugee camps in the area of Trepča (Kosovo).

Asylum seekers receiving benefits under § 1 AsylbLG and not according to § 2 get AsylbLG receive as well as their children one after § 4 AsylbLG limited to benefits in acute disease or acute need for treatment and painful disease medical care. As a discretionary benefit, it can be supplemented by benefits in accordance with Section 6 AsylbLG. The health care of these people is below that of those with statutory health insurance.

Reasons for the connection between poverty and poor health

Current models to explain the relationship do not assume that social status has a direct influence on health and life expectancy (Mackenbach 2006). Instead, social status has an indirect effect, because it is an important determinant of differences in health-related factors - such as material and psychosocial resources and stress, as well as health behavior. The opportunities and risks for health development in later life are unevenly distributed even in childhood and adolescence; this distribution can solidify in the further course of life through interactions between social status and state of health.

According to Andreas Mielck, the reasons why socially disadvantaged people fall ill more often lie in

- Differences in health stresses (e.g. stress at work)

- Differences in coping resources (e.g. social support)

- Differences in health care (e.g. doctor-patient communication).

Taken together, this in turn leads to

- Differences in health and illness behavior (e.g. diet, smoking).

Overall, these factors lead to

Health burdens

Health burdens in the workplace

Health burdens from unemployment

According to a study commissioned by the German Trade Union Federation, there is a scientific consensus that unemployment has a causal influence on health-related behavior and on the emergence of “health problems, both psychosocial and physical” . According to the study, research reveals "drastic differences between the unemployed and those in employment: Depression, anxiety, hopelessness and helplessness up to resignation as well as reduced self-esteem, a lower level of activity and loneliness are essential symptoms of poor mental health in the unemployed."

While the sick leave rate in Germany is just 4.4% for the employed, it is 7.9% for ALG I recipients and even 10.9% for ALG II recipients. The actual numbers could be even higher, as it can be assumed that unemployed people tend not to report sick when they are ill for a short time.

Environmental pollution

As early as the 19th century, social hygiene was problematizing the influence of living and working environments on people's health.

A new debate about environmental justice began in the United States when low-income and non-white groups in society began to seek environmental justice in the context of civil rights movements . A class-specific lower level of health was associated with the work and living environment and with traffic.

According to Schlüns, the thesis from Ulrich Beck's “ Risk Society”, according to which environmental pollution is more evenly distributed across the various layers of society, no longer applies in general. Recent findings have shown that affluent classes have greater opportunities to evade environmental pollution. People from the lower classes are on the one hand more exposed to environmental pollution (e.g. noise and fine dust in the living and working environment), but on the other hand they are more difficult to compensate for or cope with (e.g. due to less access to green spaces).

- see main article: Environmental Justice

Coping resources

Bonus crisis

According to the explanatory approach of the gratification crisis , people fall ill when they exert themselves too much and are not appropriately rewarded for doing so. Low-skilled workers and single mothers are particularly hard hit by the bonus crisis.

Information deficits

Antje Richter found out that socially disadvantaged people have information deficits. Socially disadvantaged people know little about:

- Avoiding risks and coping with health problems

- General health promotion and the implementation of health-related recommendations in everyday life

- Standard health care and the relevant contact persons

- Needs of children and young people and special funding opportunities

- Your rights.

Health care

| Participation in the preventive examinations U1 to U8 in Hamburg after the father's work |

|

|---|---|

| occupation of the father | Participation rate |

| Unemployed | 30.3% |

| simple workers | 38.4% |

| Skilled workers | 65.7% |

| highly skilled workers | 77% |

| Freelance | 70.4% |

| Self-employed | 67% |

The problem of social inequality in the field of medical care has not yet been extensively investigated in the Federal Republic of Germany. Interim results of a current study show that socially disadvantaged people experience psychological, social and structural barriers before using services. The children's screening examinations U1 to U9 and pain-related treatments are mentioned as examples .

There is a significant difference in the likelihood of seeing an internist . For members of social groups with few resources, the probability of visiting an internist is in principle around 16% to 29%, while for members of the upper class this probability is around 41% to 59%.

The problem of shift-specific health care is sometimes also referred to as two-class medicine , although the limit between the classes (statutory and private insurance) is between 4,800 euros / month and 5,600 euros / month (contribution assessment limit).

There are also class-specific differences in the supply of medication. For example, according to a ruling by the LSG Rhineland-Palatinate in Mainz, the cost of the drug Ritalin for adults no longer has to be covered by the statutory health insurance companies. The cheapest Ritalin generic costs between 22.32 € (lowest effective dose) and 89.28 € (high, often required dose of 80 mg per day) per month for adults.

Health behavior

nutrition

Lauterbach points to the lower quality of nutrition for children living in poverty. You would eat less fruit and whole grain bread, but more chips and french fries.

The 2nd Poverty and Health Report indicates that the differences in eating habits between poor and rich children are only minor, which, in the opinion of the Arbeiterwohlfahrt, "perhaps suggests that parents are restricting their diet in favor of their children."

This could be proven in a study.

Other health behavior

Poor children are less active in sports clubs and they are less likely to brush their teeth. There is a correlation between the level of education and smoking behavior : the proportion of smokers is higher in the lower classes than in the upper classes.

see also: smoking and social classes

Social inequality and life expectancy

For many countries there is a clear connection between the length of a person's life and their social status - as measured by their educational qualifications, professional status and / or income (Mackenbach 2006). These findings were one of the starting points for calling for a separate strategy to reduce health inequalities at European level (EU project 'Closing the Gap').

For Germany too, analyzes based on the Socio-Economic Panel ( SOEP ) show clear differences in income in relation to life expectancy (Lampert et al. 2007). Men and women from the poverty risk group live on average only 70 and 77 years old, while men and women with very high incomes live almost 10 years longer (81 and 85 years respectively). The results also indicate that the proportion of years of life spent in good health also varies significantly.

According to data from private pension insurance for the years 1995–2002, the probability of death over a year for those receiving high pensions is up to 20% lower than for those receiving low pensions. Data from the statutory pension insurance and the Federal Statistical Office show that the probability of a 65-year-old man dying within a year is almost twice as high for those insured in the workers' pension scheme as for those insured in the salaried employee insurance and for civil servants. According to an evaluation of the data from the Deutsche Rentenversicherung from 1997 to 2016 by the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, the life expectancy of people in high income groups in Germany rose almost twice as much as that of people with the lowest incomes during this period.

Social differences in life expectancy are also seen as economically relevant. For a long time , the pension expert of the SPD, Karl Lauterbach , has pointed out that the different pension periods of low-income and high-income pensioners lead to a redistribution in the system of statutory pension insurance from bottom to top (Lauterbach et al. 2006).

Political theming

The EU aims to reduce social inequality in health opportunities in Europe with two successive initiatives. The initiative Closing the Gap (2004–2007) is followed by the initiative Determine (2007–2010).

With the Bielefeld Memorandum on the Reduction of Health Inequalities, scientists want to work towards ensuring that the next health reform has the ultimate goal of reducing the increasing social divisions in the area of health.

There is a debate in Britain about whether or not it is desirable to improve the health behavior of the working class. It is feared that the ultimately paternalistic concern for the health of the working class is an obsession of the educated middle class (“obsession of the learned middle class”).

Health Secretary John Reid, son of a working-class family, stood out for this opinion. He said, “I'm just saying, let's be careful not to patronize these people. As my mother would put it, people from these low socio-economic categories have very few joys in life and one of them consider smoking ”.

literature

- U. Bauer, UH Bittlingmayer, M. Richter (Ed.): Health Inequalities. Determinants and Mechanisms of Health Inequality. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007.

- U. Bauer, A. Büscher (Ed.): Social inequality and care. Findings from applied nursing research. VS-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2007.

- Gabriele Bolte, Andreas Mielck (ed.): Environmental justice - The social distribution of environmental pollution. Weinheim / Munich 2004.

- Joachim Heinrich et al: Social inequality and environmental diseases in Germany. Landsberg 1998.

- Bita Kolahgar: The social distribution of environmental pollution and health consequences at industrial stress points in North Rhine-Westphalia. Essen 2006.

- T. Lampert, LE Kroll: Social differences in mortality and life expectancy. In: GBE compact . 5 (2) 2014. (PDF)

- T. Lampert, LE Kroll, A. Dunkelberg: Social inequality of life expectancy. In: APuZ . 42/2007. PDF (online)

- T. Lampert, T. Ziese: Poverty, social inequality and health. Expertise of the Robert Koch Institute on the 2nd poverty and wealth report of the federal government . (= Life situations in Germany ). BMGS, Bonn 2005. (Download)

- K. Lauterbach, M. Lüngen, B. Stollenwerk, A. Gerber, G. Klever-Deichert: On the relationship between income and life expectancy. In: Studies on Health, Medicine and Society. 1/2006. (PDF)

- JP Mackenbach: Health Inequalities: Europe in Profile. UK Presidency of the EU, Rotterdam 2006. (PDF)

- Andreas Mielck: Social inequality and health. Introduction to the current discussion. Bern 2005, ISBN 3-456-84235-X .

- Julia Schlüns: Environmental Justice in Germany. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. No. 24 / June 11, 2007. (online)

- Karin Tiesmeyer, Michaela Brause, Meike Lierse: The blind spot. Inequalities in health care. KBT Huber & Partner, 2007, ISBN 978-3-456-84493-0 .

Web links

- EU side on health inequalities

- Conference on Health Inequalities

- Health inequality in Switzerland Federal Statistical Office

- The social and spatial unequal distribution of environmental pollution in the context of child poverty in Germany. ( Memento of May 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) 12th international congress “Poverty and Health” (PDF file; 184 kB)

- Smoking and social inequality (PDF file; 50 kB) German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ)

- BzgA: “Closing the Gap”: Reducing health inequalities in Europe

- Recent scientific studies "Health and Social Inequality"

- Gopal Sreenivasan: Justice, Inequality, and Health. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ^ Günther Steinkamp: Social inequality, risk of disease and life expectancy: Critique of social epidemiological inequality research. In: Social and Preventive Medicine. 38 (3), 1993, pp. 111-122, 112-113.

- ^ Siegfried Geyer: Social Inequality and Health / Illness (2016) . In: Federal Center for Health Education (Ed.): Key terms in health promotion - online glossary . doi : 10.17623 / bzga: 224-i109-1.0 .

- ↑ Uwe Helmert and others: Do the poor have to die earlier? Social inequality and health in Germany. Juventa, 2000, ISBN 3-7799-1192-2 .

- ↑ A. Mielck (Ed.): Illness and social inequality . Leske + Budrich, Opladen.

- ^ WHO - Health and health inequalities. ( Memento from December 30, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ WHO - World Health Report

- ↑ Life expectancy in parts of Africa under 33 years. ( Memento of the original from October 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. vista verde news, accessed December 18, 2006.

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2013. Hunger and malnutrition have many causes. Background.

- ↑ Poverty takes a heavy toll on children. On: Wissenschaft.de from January 5, 2007.

- ↑ apoverlag.at ( Memento from December 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ europa.s-cool.org

- ^ A b c J. Goldberg, W. Hayes, J. Huntley: Understanding Health Disparities. Health Policy Institute of Ohio, Nov. 2004, pp. 4-5.

- ^ A b American Public Health Association (APHA), Eliminating Health Disparities: Toolkit (2004).

- ↑ Fast food instead of vitamins: In the food desert. taz, October 22, 2010, accessed November 1, 2010 .

- ↑ Martin Winkelheide : GENETICS - The social status can be read from the chromosome ends cf. PNAS , Deutschlandfunk - “ Research News ” from April 7, 2014.

- ^ Sarah Gold: PTSD and social class. Trauma Alliance.

- ↑ Jennifer L. Price: Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans' Readjustment Study - Factsheet. ( Memento of the original from September 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. National Center for PTSD. United States Department of Veterans Affairs (accessed September 27, 2012).

- ↑ a b c d Elzbieta Tarkowska: Child poverty and social exclusion in Poland. (Translation from the English by Rudolph Müllan). In: Margherita Zander: Child poverty . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14450-2 , pp. 39-40.

- ↑ Lodz Voivodeship: The Voivodeship Program for Prophylaxis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. 2003.

- ↑ Hans Schlack: Lebenswelten von Kinder. In: Hans Schlack (Ed.): Social paediatrics - Health - Illness - Lifeworlds. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart / Jena / New York 1995, ISBN 3-437-11664-9 , p. 90.

- ^ Press release from the Berlin Social Science Center: More jobs, but also more poverty. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ Robert Koch Institute: Poverty and Health. (PDF download 836 kB) (accessed November 26, 2013).

- ↑ J. Winkler: The importance of recent research on social inequality of health for general sociology. In: Helmert u. a .: Do the poor have to die earlier? Juventa, Weinheim / Munich.

- ↑ J. Winkler, H. Stolzenberg: The social class index in the Federal Health Survey. In: Healthcare. 61.Special Issue 2, 1999.

- ↑ faz.net article on Children's Report Germany 2007 from November 15, 2007.

- ↑ Antje Richter: Poverty Prevention - A Mission for Health Promotion. In: Margherita Zander: Child poverty. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14450-2 , p. 203.

- ^ Robert Koch Institute: Federal Health Reporting. Booklet 4: Poverty among children and adolescents. (accessed on September 27, 2012).

- ^ Magazine Mitbestigung 1 + 2/2006 (Hans Böckler Foundation): Interview with Klaus Peter Strohmeier: "It looks bleak for our society". (accessed on September 27, 2012).

- ^ A b Robert Koch Institute: Federal Health Reporting - Issue 13: Unemployment and Health. February 2003. (accessed September 27, 2012)

- ↑ Kerry E. Bolger, Charlotte J. Petterson, William W. Tompson: Psychological Adjustment among Children Experiencing Persistent and Intermittent Family Economic Hardship. In: Child Development. 66, 1995, pp. 1107-1129.

- ↑ Avshalom Caspi, Glen H. Elder, Ellen S. Herbener: Childhood Personality and the Prediction of Life-course Patterns. In: Lee N. Robins, Michael Rutter (Eds.): Straight and Devious Pathways from Childhood to Adulthood. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, pp. 13-35.

- ↑ Robert Koch Institute / Federal Statistical Office: Federal Health Reporting, Volume 14: Health of single mothers and fathers. (accessed on September 27, 2012).

- ↑ Report "Health of Mothers and Children Under Seven Years" from the Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine of the University of Zurich from January 13, 2006, quoted from uzh.ch (accessed on January 29, 2008).

- ↑ On this issue there was a complex of topics during a conference in Bielefeld: Health Inequalities V (2010) ( Memento of the original from January 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Antje Richter: Poverty Prevention - A Mission for Health Promotion. In: Margherita Zander: Child poverty . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14450-2 , p. 202.

- ↑ At least half of the refugees are mentally ill. Federal Chamber of Psychotherapists, September 16, 2015, accessed on October 19, 2016 .

- ↑ Traumatized refugees are treated too late and often not at all. Bertelsmann Foundation, accessed October 29, 2016 .

- ↑ Elena Gomes de Matos: Migration Background and Alcohol Consumption in Germany: Risk or Protection Factor? In: Abstract for the 39th Congress of the Association for Drugs and Addiction Aid. V. (FDR). Retrieved April 29, 2018 .

- ↑ A. Zittermann, S. Pilz, H. Hoffmann, W. March: Vitamin D and airway infections: a European perspective. In: European Journal of Medical Research. Vol. 21, 2016, p. 14. PMID 27009076 .

- ↑ C. Braegger, C. Campoy, V. Colomb, T. Decsi, M. Domellof, M. Fewtrell, I. Hojsak, W. Mihatsch, C. Molgaard, R. Shamir, D. Turck, J. van Goudoever: Vitamin D in the healthy European pediatric population. In: Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Vol. 56, No. 6, 2013, pp. 692-701. PMID 23708639 .

- ↑ Eat healthy with joy. ( Memento from May 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Prevention project on bkk.de (accessed on August 30, 2012).

- ↑ Kosovo: Poisoned by Lead . Human Rights Watch report on lead poisoning in Roma camps near the Trepča lead mine.

- ↑ Mielck, 2005, p. 53.

- ↑ DGB: Unemployment health risk - level of knowledge, practice and requirements for health promotion that integrates labor market. In: Current job market. No. 9 August 2010, p. 2f. (PDF download 1.4 MB, accessed on September 27, 2012).

- ^ Julia Schlüns: Environment-related justice in Germany. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. No. 24 / June 11, 2007, pp. 26-31. (accessed August 30, 2012).

- ↑ Antje Richter: Poverty Prevention - A Mission for Health Promotion. In: Margherita Zander: Child poverty . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14450-2 , p. 201.

- ↑ Roland Merten: Psychosocial consequences of poverty in childhood and adolescence . In Christoph Butterwegge, Michael Klundt (ed.): Child poverty and intergenerational justice. Leske + Budrich, Opladen 2002, ISBN 3-8100-3082-1 , p. 150.

- ^ Social inequality in health care. The Influence of Social Factors on Performance in the German Health Care System , Congress Medicine and Society 207. Augsburg, 17. – 21. September 2007.

- ↑ Nicole Thode, Eckardt Bergmann, Panagiotis Kamtsiuris, Bärbel-Maria Kurth: Influential factors on the use of the German health system and possible control mechanisms. S. 88. (accessed on August 30, 2012)

- ↑ No entitlement of adults to Ritalin for ADHD ( Memento of the original from July 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed January 1, 2008).

- ^ Wolfgang Lauterbach: Poverty in Germany - Consequences for families and children . Oldenburg University Speeches , Oldenburg, ISBN 3-8142-1143-X , p. 31.

- ↑ Arbeiterwohlfahrt: Statement by the Federal Association of Arbeiterwohlfahrt e. V. on the 2nd National Poverty and Wealth Report of the Federal Government ( Memento from May 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Antje Richter: Poverty Prevention - A Mission for Health Promotion. In: Margherita Zander: Child poverty . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-531-14450-2 , p. 206.

- ^ Wolfgang Lauterbach: Poverty in Germany - Consequences for families and children . Oldenburg University Speeches , Oldenburg, ISBN 3-8142-1143-X , p. 31.

- ↑ Thomas Lampert, Lars Eric Kroll, Annalena Dunkelberg: Social inequality of life expectancy in Germany. In: From Politics and Contemporary History. (APuZ) 42/2007. (accessed on April 24, 2014)

- ↑ Derivation of the DAV 2004R mortality table for pension insurance ( memento of the original from April 27, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Study: Rich retirees live longer. In: web.de/magazine. April 16, 2019, accessed April 17, 2019 .

- ↑ K. Lauterbach, M. Lüngen, B. Stollenwerk, A. Gerber, G. Klever-Deichert: On the relationship between income and life expectancy. In: Studies on Health, Medicine and Society. 1/2006 (accessed on April 24, 2014, PDF 455kB)

- ↑ Europe Project Health Inequality

- ↑ Bielefeld Memorandum on Reducing Health Inequalities. ( Memento of the original from August 19, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed on September 27, 2012; PDF; 24 kB).

- ↑ Smoking ban is just 'obsession of middle class', says minister. In: The Telegraph. June 9, 2004.

- ^ Smoking 'working class pleasure'. on: news.bbc.co.uk June 9, 2004.