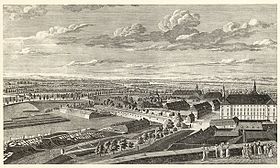

Mannheim observatory

The Mannheim observatory was located in the observatory tower, which was built from 1772 to 1774, and remained in operation until 1880. The observatory was then moved to Karlsruhe and, in 1898, to the Königstuhl near Heidelberg , where the successor institute still exists today as the State Observatory Heidelberg-Königstuhl .

Prehistory of the observatory in Schwetzingen

The Palatinate Elector Carl Theodor was open to the impulses of the Enlightenment . The French thinker Voltaire was a guest at his court several times , the elector carried out numerous reforms in his dominion and founded scientific institutions. One of them, the physical cabinet, was built by the professor of experimental physics and mathematics , who had been in Heidelberg since 1751 , the Jesuit father Christian Mayer .

When Mayer was sent to Paris in 1756 to study the local water supply, he also got to know one of the contemporary centers of astronomy there. He bought an astronomical instrument, a quadrant, from the instrument maker Canivet . With him he observed the comet's return, predicted by Edmond Halley , in 1759 in the Electoral Palatinate .

In 1761, Carl Theodor had a provisional wooden observatory built in the orangery of the Schwetzingen Palace Park , from which Mayer observed the passage of Venus in front of the sun on June 6th. The observations must have convinced the elector, because work on an observation building on the castle roof, which was inaugurated in 1764, began in July.

A few years later Mayer traveled to Saint Petersburg for a year and observed, among other things, the passage of Venus on June 3, 1769. The Schwetzingen observatory was not unused, Carl Theodor and his guest Prince Franz Xaver of Saxony also wanted to observe the natural spectacle, but they did failed due to bad weather.

While still in Saint Petersburg, Mayer published his results from the transits of Venus and, with the help of all the observations of the two transits known to him, calculated the mean distance Earth-Sun to be 146.2 million kilometers, which is only three million kilometers less than the actual value, however with a considerable measurement uncertainty.

Electoral Palatinate period

The time when the Mannheim observatory was founded

On New Year's Eve 1771, Mayer finally presented a memorandum on the construction of an observatory near the Mannheim court, and in 1772 the elector commissioned the court chamber to build the new observatory. In the same year the foundation stone of the tower was laid next to the Mannheim Palace , near the Jesuit College . With the help of the instruments acquired in the following years and the numerous books left from the electoral library, Mayer made the Mannheim observatory into a well-known and internationally equal research facility.

The Mannheim observatory's guest book not only contains entries from numerous well-known colleagues, but also from illustrious guests such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , who applied to be court conductor, Benjamin Franklin as envoy from the young United States, and even those in Arabic and other writings.

Mayer's astronomical work reached its climax with the discovery of the double stars as related structures. Most of the binary stars published in Bode's Sky Atlas in 1782 were observed by Mayer.

Carl Theodor left the Electoral Palatinate in 1778 to rule Bavaria . Not least because of the absence of a personally caring prince, the history of the observatory was less fortunate after the death of Christian Mayer in 1783.

Christian Mayer's successors

The new court astronomer , the Jesuit Karl König, was soon transferred to Munich by the elector, the next, the ex-Jesuit Johann Nepomuck Fischer , made so many enemies that he left after only a year and a half in 1788. A better choice was made with the Lazarist Peter Ungeschick, but he died as early as 1790 on the return journey from a study visit to Paris. He was followed by Roger Barry , also a member of the Order of the Lazarists.

Barry's initial successes were ruined by the wars of the Napoleonic era, which also severely affected the observatory. The tower was shot at several times, instruments were destroyed, others damaged. Some also disappeared in mysterious ways. Barry, temporarily even imprisoned by the French, was given the opportunity to observe a passage of Mercury , but otherwise could do little.

Baden time

From the Napoleonic Wars to the German Revolution

After the war, in 1806, the Grand Duchy of Baden took over the areas of the Electoral Palatinate on the right bank of the Rhine, including the observatory. The court astronomer Roger Barry resumed his observations, but fell ill in 1810 and the observatory remained unused until his death in 1813. His numerous observations with the wall quadrant after 1800 remained unpublished because his successors classified them as out of date.

The time of the Catholic orders at the Mannheim observatory was over. In the years up to the Baden revolution in 1848, the observatory lagged behind its brilliant beginnings. Famous astronomers could either not be retained , such as Heinrich Christian Schumacher (1813–1815 in Mannheim), who founded the oldest still existing specialist journal on astronomy, the Astronomical News , at his subsequent place of work in Altona , or were deterred by unskillful personnel policy despite interest. like Friedrich Wilhelm Struwe , who then set up a renowned observatory in Pulkowa near Saint Petersburg. In 1815 an attempt was made to move the Munich astronomer Johann Georg von Soldner to Mannheim, but he also refused. From 1816 until his death in 1846, Bernhard Nicolai was court astronomer who mainly devoted himself to the orbits of comets. During his time, Fraunhofer bought a telescope with an opening width of 7.5 cm , which was later used in the expeditions to observe the passages of Venus in 1874 and 1882.

The instruments and the observatory tower itself were getting on in years. Well-developed plans for a new observatory could no longer be realized during the revolutionary era. On June 10, 1850, the decision was made to abolish the institute by not appointing a new court astronomer. The Heidelberg professor Nell took over the supervision in 1852, but without a salary. Again, a more modest renewal of the institute was planned, which began in 1859 with the order for a telescope with an opening width of 9 cm.

Relocation to Karlsruhe

In 1860, Eduard Schönfeld , a paid court astronomer came to Mannheim again, who soon made a name for himself through his observations of astronomical nebulae . With his work, he made a significant technical contribution to the catalog of the "Bonn survey", which is still used today. In addition, he organized several astronomical meetings. At such a meeting on 28 August 1863 was in Heidelberg Astronomical Society of Germany established that still exists today. Schönfeld was elected to the founding board. In addition to many other activities, in 1871 he took part in the advisory commission for the preparation of the Venus passage in 1874/82.

When Schönfeld went to Bonn in 1875 to become director of the observatory there, Wilhelm Valentiner took over the Mannheim position. The location in the middle of the city was no longer in keeping with the times. The observatory was moved to Karlsruhe and housed there in a makeshift hut in 1880, from which, however, no observations worth mentioning could take place. Plans to build a permanent observatory in Karlsruhe were, much to Valentin's annoyance, not realized, although the first telescopes and instruments were purchased.

During this time the desire for an observatory also arose at the University of Heidelberg. The young Heidelberg astronomer Max Wolf built a private observatory in his parents' house as early as 1880. He consistently relied on photography for observation and quickly made a name for himself in astronomy.

Bergsternwarte Heidelberg

In 1892 a deputation from Heidelberg professors, including Max Wolf, presented the Karlsruhe Grand Duke with the wish for a university observatory suitable for research and teaching. Baden, which was not exactly financially strong at that time, could hardly do more than erect the buildings and the Karlsruhe instruments were unsuitable for Wolf's specialty, astrophotography . So Wolf was looking for sponsors who would enable him to purchase new telescopes. The search turned out to be extremely fortunate: US science patron Catherine Wolfe Bruce donated $ 10,000 for a telescope, and her foundation was followed by more. Finally, the construction of an observatory near Heidelberg was approved, to which the Karlsruhe instruments should also be transferred.

On June 20, 1898, the “Grand Ducal Mountain Observatory” on the Königstuhl (today's State Observatory Heidelberg-Königstuhl) was inaugurated. Initially there were two competing departments. The astrometric department was headed by Wilhelm Valentiner and included the Karlsruhe instruments. The astrophysics department under Max Wolf was equipped with the instruments from his private observatory and the new foundation instruments. After Valentin retired in 1909, both departments were combined. Wolf worked in many areas of astrophysics; he examined the structure of the Milky Way , spectroscoped stars and gas nebulae and searched intensively for small planets , of which more than 800 were discovered at the observatory. As an honorary citizen of Heidelberg, he was buried in the mountain cemetery in 1932.

After the Second World War there was a new beginning for the institute, which was now called the Königstuhl State Observatory (LSW). The Mannheim instruments were donated in 1983 to the State Museum for Technology and Work, today Technoseum , in Mannheim, where some of them are part of the permanent exhibition. The telescope from 1859 was given to the city of Karlsruhe in 1957 for the construction of the Volkssternwarte Karlsruhe , another instrument of the Volkssternwarte Heppenheim . The books of the old library, the oldest of which dates from 1476, were transferred to the manuscript department of the university library by the institute.

History of the Mannheim observatory after 1880

The tower of the observatory was restored from 1905 to 1906. Due to a heritable building contract between the state treasury and the city of Mannheim in 1940, the building came into the care of the city of Mannheim until March 31, 2021. During the Second World War, the building was badly damaged on March 20, 1944 by an explosive bomb that penetrated the top vaulted ceilings. After the Second World War, a makeshift repair was carried out. It was not until 1957 that the town council decided to restore it and convert it into a studio house. As a result of the subsequent renovation work up to October 1958, the facade was given a largely original appearance, and studio rooms were created inside. Currently (2015) the Mannheim artists Walter Stallwitz (since 1958), Edgar Schmandt (since 1963) and Ute Dora use these studios. On the upper deck of the building is still serving as a zero point for the Baden surveying system level measurement - pillar .

The Baden-Württemberg Monument Foundation named the observatory Monument of the Month for June 2014 . In October 2019, for Mayer's 300th birthday, the historic dome was again placed on an octagonal substructure.

literature

- Kai Budde: Mannheim observatory. The history of the Mannheim observatory 1772–1880 . (= Technology + Work 12. Writings of the State Museum for Technology and Work in Mannheim). Ubstadt-Weiher, regional culture publisher 2006. ISBN 978-3-89735-473-9

- Alexander Moutchnik : Research and teaching in the second half of the 18th century. The natural scientist and university professor Christian Mayer SJ (1719–1783) (= algorism, studies on the history of mathematics and natural sciences, vol. 54), Erwin Rauner Verlag, Augsburg, 523 pages with 8 plates, 2006. ISBN 3-936905-16 -9 http://www.erwin-rauner.de/algor/ign_publ.htm#H54 Table of contents: http://www.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/tocs/178692786.pdf

- Thomas Schoch: The Mannheim observatory and its court astronomer Christian Mayer 1763–1783 , 1986, University of Mannheim, in the Marchivum

- Emil Lacroix: The former observatory in Mannheim. Report on their repairs in 1958 , newsletter of the preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg - Organ of the State Offices for Monument Preservation, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1959), (PDF 6.4 MB).

Individual evidence

- ^ Kai Budde: Mannheim Observatory, History of the Mannheim Observatory 1772–1880, State Museum for Technology and Work in Mannheim, regional culture publisher 2006, page 135

- ^ The restoration of the observatory, in: Mannheimer Hefte 2/1958, pp. 14-15

- ↑ Monuments : We have completed something here , issue 1/2020, page 11.

Web links

- Observatory's guest book from 1777

- Description and functionality of the Mannheim Wall Quadrant

- Rhein-Neckar industrial culture, Mannheim observatory with the Mannheim meridian (Mire) in the industrial port (Kaiser-Wilhelm-Becken)

- Action alliance "Old Observatory"

Coordinates: 49 ° 29 ′ 11.3 " N , 8 ° 27 ′ 34.9" E