Türkenschanzpark

The Türkenschanzpark is a park in the 18th district of Vienna, Währing . The park was opened on the Türkenschanze in 1888 .

history

The Türkenschanzpark is located in a historical location. In 1683, in the course of the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna, there was a redoubt of the Turks . Nevertheless, the name of the area is a mystery, since the area was already noted as "Turkenschanz" in a topographical representation from 1649. The name probably goes back to the First Turkish Siege of Vienna , but there are no descriptions or references to it.

The area remained undeveloped for a long time, it consisted of cornfields and meadows. In addition, yellow building sand and gravel for Vienna was mined here for centuries. The “Schreibersche Sandgrube” became particularly well known in the 19th century. It was not until 1873 that the first houses of the Viennese cottage were built on the Türkenschanze .

After plans to create a cemetery or to build a general staff palace were discarded and the 50 yoke (28.8 ha ) site was parceled out for houses with front gardens at the beginning of March 1883, a “Comité” was formed in the independent town of Währing to create a public one Parks on the Türkenschanze ”with the architect Heinrich von Ferstel (1828–1883), who gave the idea, as his vice-president. After Ferstel's death in July of that year, the association was founded under the honorary presidency of Leopold Friedrich von Hofmann (1822–1885), which held its first general assembly on October 28, 1883 with 42 members and the architect Carl von Hasenauer (1833– 1894) acclaimed as the new Vice President . Archduke Carl Ludwig took over the protectorate of the association .

The following were elected to the executive committee: Carl von Hasenauer as chairman, Edmund Weiss as chairman deputy, Josef Aigner , Raimund Grübl , publicist Ludwig Benedict Hahn (1844–1925), mayor of Ober-Döbling Franz Kreindl (1840–1908), Friedrich Franz Josef von Leitenberger (1837–1899), Theodor Leschetizky , Ferdinand Oberwimmer, lawyer Theodor Reisch (1841–1919), writers Friedrich Schütz (1844–1908), Wilhelm Stiassny , Karl Umlauff von Frankenwall (1837–1891) and Mayor of Währing Friedrich Wagner (1828-1897).

With regard to the financing of the property, commitments have already been made, including over 10,000 guilders from the Vienna City Expansion Fund , 5,000 guilders from the municipality of Währing, 3,500 guilders from the municipality of Ober-Döbling , 1,000 guilders as the first of six contributions from the Wiener Cottage Verein and 3,000 guilders from City architect Ferdinand Oberwimmer (1836–1895), who, together with the leather manufacturer and local politician Jacques Gerlach († January 3, 1905 at the age of 63), had acquired around 70,000 m² of land and initially made it available to the association until July 1894.

The association hired the Vienna City Garden Director Gustav Sennholz (1850–1895), under whose direction the park was laid out in the style of an English landscape garden from 1885. The old firing trench was heaped up about 2.5 m high, the terrain excavated four meters elsewhere provided excavation for the filling of an artificial mountain on which the Paulinenwarte (a lookout tower named after its sponsor Pauline von Metternich ) was built. For the structure, which was intended as a shell or cover for a previously constructed reservoir system, the first sketches were available from the hand of the architect Hermann Müller (* 1856, † unknown), who worked for the Cottage Association , but the construction costs were too high in their implementation that resulted in an agreement on a design by the architect and town builder Anton Krones senior. (1848-1912). Just as laborious as the work on the foundation of the tower, the founding of a long-defunct Italian renaissance three-storey restoration building (conversion, among others, in 1909), which, not far from the entrance on today's Gregor-Mendel-Strasse , was based on plans by Architect Wilhelm Stiassny (1842-1910) was built.

On September 30, 1888, Emperor Franz Joseph I opened the park. The speech that the emperor (presumably on the advice of his childhood friend, Imperial and Royal Prime Minister Eduard Taaffe ) gave on this occasion caused stormy cheers and three cheers and was featured in the leading daily newspaper of the monarchy as a top report the next day. It had a positive effect on the further development of Vienna. Franz Joseph noted that it was his wish that the “physical union” of the suburbs, such as Währing, with the city of Vienna should take place soon. In doing so, the emperor referred to negotiations that had been going on for fifteen years to enlarge Vienna by incorporating suburbs. The gentle pressure exerted by the emperor meant that the relevant Lower Austrian provincial law came into effect in 1890 and 41 suburbs came to Vienna on January 1, 1892.

In December 1892, the park became the property of the City of Vienna in return for the costs and charges. Just five years after it opened, the green space, which was heavily neglected for financial reasons, had to be extensively regenerated. In 1908, under the district chairman Anton Baumann, the expansion was decided after the state had sold the city in the course of the barracks transaction , and was completed by 1910 by city planner Heinrich Goldemund and city gardening director Wenzel Hybler.

In 1926 a children's outdoor pool was built in the park , which was repaired after the war and existed until 1991.

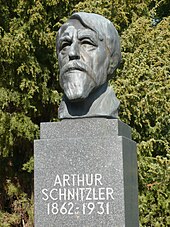

In addition to ponds, streams and fountains, there are a number of monuments in the park, for example for the poet Adalbert Stifter or for the composers Franz Marschner and Emmerich Kálmán , as well as the actor Leon Askin . In 1991 the Yunus Emre Fountain was unveiled, donated by the Turkish ambassador as a token of Austro-Turkish friendship . Since 1999, a 2,500 m² "leisure world" with ball sports facilities and a skate facility has also been available. The Paulinenwarte has been accessible again since 2010 after the building had been closed for around 25 years due to dilapidation.

In the course of a collaboration with the neighboring University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences , numerous botanical rarities from all continents were planted.

literature

sorted alphabetically by author

- Walter Frenzel: Natural history guide through the Wiener Türkenschanzpark with special consideration of the woody flora . Kaltschmid, Vienna 1952, OBV .

- Christian Hlavac: The Wiener Türkenschanzpark: "A huge green island in the middle of a Viennese villa quarter" . In: Die Gartenkunst 26 (1/2014), pp. 49–72.

- Cordula Loidl-Reisch: Türkenschanzpark . In: Christian Hlavac, Astrid Göttche, Eva Berger (all eds.): Historical gardens and parks in Austria . Böhlau, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-205-78795-2 , pp. 349–356.

- Christoph Prem (text): 125 years of the Türkenschanzpark. An eventful history 1888–2013 . MA 42 (Vienna City Gardens), Vienna 2013, OBV .

- Manfried Welan and Peter Wiltsche: The green jewel. The Türkenschanzpark and its monuments . Platform Johannes Martinek Verlag, Perchtoldsdorf 2016, ISBN 978-3-9503682-8-4 .

Web links

- Wiener Stadtgartenamt - Türkenschanzpark

- Entry on Türkenschanzpark in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

Individual evidence

- ↑ See: Vienna Communal Affairs. From the suburbs. (...) Park on the Türkenschanze. In: Morgen-Post , No. 301/1883 (XXXIIIth year), November 2, 1883, p. 3, center left. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ Little Chronicle. (...) Park on the Türkenschanze. In: Wiener Zeitung , No. 251/1883, October 31, 1883, p. 7, top center. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ The restoration building and the observation tower in the park on the Türkenschanze near Vienna. In: Der Bautechniker , year 1888, No. 49/1888, December 7, 1888 (VIII. Year), p. 695 f. (Online at ANNO ). .

- ^ Daily newspaper Neue Freie Presse , Vienna, No. 8858, October 1, 1888, p. 1, left column

- ↑ Law of December 19, 1890 regarding the unification of several municipalities ... In: ALEX . Retrieved April 16, 2018 .

- ↑ Cordula Loidl-Reisch: Türkenschanzpark . In: Géza Hajós (concept, ed.), Matthias Cremer (photo): Historical gardens in Austria - forgotten total works of art . Böhlau, Vienna (inter alia) 1993, ISBN 3-205-98095-6 , p. 300.

- ↑ New children's outdoor pools and playgrounds. In: Wiener Zeitung , March 3, 1926, p. 3 (online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ The reconstruction of the Vienna baths. In: Weltpresse , May 10, 1947, p. 5 (online at ANNO ). .

- ↑ Christian Hlavac: From the Bürgerpark in front of the city to the municipal city park: 125 years of Wiener Türkenschanzpark. In: stadtundgruen.de . July 17, 2013, accessed September 10, 2019.

- ↑ Manfried Welan and Peter Wiltsche: The green jewel. The Türkenschanzpark and its monuments . Platform Johannes Martinek Verlag, Perchtoldsdorf 2016, ISBN 978-3-9503682-8-4 .

- ↑ Türkenschanzpark: The Paulinenwarte can be climbed . In: diepresse.com , August 5, 2010, accessed June 3, 2014.

Coordinates: 48 ° 14 ′ 5 ″ N , 16 ° 20 ′ 0 ″ E