Tara Bai

Tara Bai , hindi / marathi ताराबाई, also Rani Tara Bai , Tarabai or Tara Bye , b. 1675 as Sita Bai ; died December 9, 1761 in Satara in today's Maharashtra , was regent in the Marathas Empire in north-west India from 1701–1708 . As the daughter-in-law of the founder of the state, Chatrapati Shivaji from the Bhonsle (भोंसले) dynasty (1630–1680), she managed to maintain the independence of the Maratha principality in a critical phase after the death of her husband, her son Shivaji II. (1696–1680) 1726) to gain the throne and himself the reign and to stop the advance of the Mughals .

Stripped of power by her relatives at the court in Satara, she managed to install the rival dynasty of the Bhonsle of Kolhapur, which still exists today, in disputes with her own family and to become regent in Satara again for a short time.

Live and act

Birth, origin and marriage 1675–1700

Tara Bai came from the Kshatriya warrior noble family of the Mohite (मोहीते) and was a cousin, from the age of eight she was also the wife of the Marath prince Raja Ram (* 1670, r. 1689, † 1700); her father was the senapati (general) of the Marathas, Hambir Rao Mohite . Tara Bai was only one of her husband's four official wives. Her husband Raja Ram (ruled 1689–1700), the younger son of the founder of the state Shivaji Bhonsle , came to power only after the capture and execution of his older brother Sambhaji II (ruled 1680–1689). He was considered a militarily capable ruler who managed to hold the Marathas fortress Gingi in the Tamil region of southern India, where he fled after the death of his brother, for nine years against a Mughal siege army; sociable and mild, he was without formal education and politically weak. In the besieged Gingi, Tara Bai gave birth to their only son, the later ruler Shivaji II (* 1696, ruled 1700–1703, † 1726).

Tara Bai was considered beautiful, but was feared and respected rather than popular because of her intellect, ambitions and dominant personality and strength of character. During her husband's absence from 1689 to 1694, she had acquired administrative and military knowledge under the guidance of the experienced Prime Minister Ramchandra Nilkanth . In 1694, the nineteen-year-old set out with the other wives by sea around Cape Comorin to the besieged Gingi to live by her husband's side. While Rajaram was able to escape before the fortress fell in 1697, Tarabai was allowed to return home unmolested from captivity with her two-year-old son, Rajaram's first son from a legitimate marriage, and the rest of the family. In a dispute over a court office, Tara Bai prevailed against her own husband, leading a contemporary observer to say that she was "a stronger ruler than her husband" and that no marathist would dare to act without her order; the Portuguese in Goa called her "Queen of the Marathas" as early as 1701. Raja Ram moved the court to Satara in 1699 and carried the war into the Mughal region; at the age of only 30 he died of natural causes after the efforts of a military campaign in Berar Province .

Regency, fight against Emperor Aurangzeb 1700–1708

After the death of Raja Ram, one of the wives committed Sati , later the second died, while Tara Bai and his second wife Rajas Bai, who also had a son of Raja Ram, had other plans. Fractions formed around the aspirants to the throne at court, and initially the unequal Karna, who came from a connection with a concubine, was elevated to the status of the new Chatrapati of the Marathas; in order to secure the throne for her own four-year-old son, she had the ceremony of conferring the triple cord of the Brahmin performed on him, thereby fulfilling an important requirement for the legitimate occupation of the throne. In addition, she made Emperor Aurangzeb an offer of submission, which would have declared her son a Mughal nobleman, but at the same time the dominant Zamindar and Deshmukh (tax and landlord) of the entire Deccan; However, the suspicious Aurangzeb did not accept the offer and continued his expansion efforts southwards in order to incorporate the Hindu marathon state as well as the neighboring Muslim sultanates of Bijapur in 1686 and Golkonda in 1687 as Subah (province) into the kingdom of Delhi.

When Karna died of smallpox after only three weeks, Tara Bai succeeded against the resistance of the younger second wife, Rajas Bai, in helping her own son Shivaji to the Gaddi (throne) ; as regent she now energetically seized the reins of government on behalf of the minor.

The capture of the capital Satara by enemy troops a few weeks later forced Tara Bai to wage an ever-expanding guerrilla war from changing bases with her highly mobile cavalry troops , which the Mughal armies successfully ended despite the capture of numerous mountain fortresses in the Sahyadri coastal mountains of the Western Ghats did not succeed. It was only thanks to their energetic, sweeping leadership, often with personal commitment, that the fortress and troop commanders remained loyal to the Princely House and did not give up the resistance; In the meantime, the emperor Aurangzeb himself, who was well over eighty years old and personally led his troops, faced her. At the same time, Tara Bai gradually managed to set up parallel structures in regions under Mughal rule, so that taxes, customs duties and levies were also paid in the name of the Chatrapati in the surrounding areas.

"Her administrative genius and her strength of character saved the nation from the terrible crisis that threatened it as a result of Rajaram's death, the controversial succession and Aurangzeb's repeated victories between 1699 and 1701."

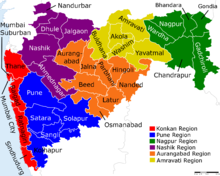

When her son became mentally ill in 1703, she put him down without further ado and had him locked up; until 1707 she ruled alone in his name. At the time of the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707, who had relocated the imperial capital to the south, to Aurangabad , for the purpose of waging war , the Marathas capital Satara was again in the possession of the Marathas; under Tara Bai's leadership, her extremely mobile cavalry troops carried the war into the neighboring regions of Khandesh , Malwa and Gujarat after 1705 and carried out their forays partly under the eyes of the imperial army.

“Soon afterwards it was said that the eldest son, a boy of five, had died of smallpox. The nobles then made Tara Bai, the main wife, regent. She was a cunning, intelligent person and had built a reputation for her knowledge of civil and military affairs during her husband's lifetime. Tara Bai withdrew into the impassable mountainous country. At this news the emperor let the drums of joy beat, the soldiers congratulated each other and said that another stone had been cleared and it was no longer difficult to overpower two small children and a helpless woman. They considered their enemy weak, contemptible and helpless, but Tara Bai - that was the name of the wife of Ram Raja - showed great ability in command and rule, and day by day the war expanded and the power of the Marathas grew. "

Fight against Prince Shahu 1708–1714

After Shivaji's eldest son and her husband's older brother, Prince Sambhaji (1657–1689), was captured, tortured and executed in 1689, his son Shahu (1682–1749) and his mother Yesu Bai brought the following eighteen Years up to 1707 as a hostage in honorary custody in the immediate vicinity of Emperor Aurangzeb (1618–1707), where he got to know the customs, way of thinking and religion of his opponents, but refused to convert to Islam and was brought up in the Brahmanic tradition; the daughter of the emperor herself raised the boy Shahu in the harem.

After the emperor's death, his son Azam released Prince Shahu in 1708, hoping to sow conflict in the Marathen camp. When Shahu now claimed the throne of Satara for himself, Tara Bai first declared him a deceiver, then, when his identity was confirmed, opposed the returning nephew in the name of her son; his father Sambhaji lost his right to the government through his death in captivity and only her own, now deceased husband, Rajaram, maintained the principality for 10 years; she herself then defended the country as regent for eight years against the enemies of the country. In the meantime he himself had become a mogul, by the heir to the throne Bahadur II. He was even confirmed in office and therefore no longer a trustworthy Maratha.

Tara Bai had to experience that the circles at court and in the military, especially their prime minister or vizier , the Peshwa , gave priority to the descendants of Shivaji in a direct line, so that Shahu could move into Satara as prince in 1708 after winning a battle. Shahu endowed the Peshwa who brought him to power with extensive administrative and financial powers. Under him, the Marathas became a leading power in the north of the country. From then on there were two Maratha kingdoms, the one Shahus in the north with the capital Satara, the other Tarabais with the capital Kolhapur in the south, which faced each other bitterly. Tara Bai sparked an eight-year succession and civil war against the parent company in Satara and tried to win over the deshmukhs (little princes) of the country from her residence in Kolhapur and from constantly changing locations . They also called the Mughals - again with the offer of cooperation and again in vain - for a Sanad ("permit, document") to acknowledge their claims. The country sank into chaos in 1713 the Peshwa succeeded in capturing them, and when he received the tax collection in his area from the Mughal court in Delhi in 1719, the decision had been made to the advantage of their opponents.

Imprisonment 1714-1730

A palace revolution in favor of the son of the second wife of her deceased husband, Rajas Bai, brought him to power in 1714 as Sambhaji II (* 1698, r. 1714–1760, † 1760) in Kolhapur ; Tara Bai and her son Shivaji II immigrated to the prison of the Panhala fortress , where they were held for 16 years and her son for twelve years (until his death in 1726), and so she was also excluded from rule in this branch line.

The dynastic controversy over the succession to the throne of the Bhonsles of Satara and the younger line of Kolhapur continued, however, regardless of Tara Bai's disempowerment, until a battle in 1730 decided the succession in favor of Shahu of Satara; In 1731 Sambhaji II finally had to settle for rule over the narrower area around his capital in the Treaty of Varna and thus became the first Raja of Kolhapur.

House arrest 1730–1748

Tara Bai's nephew, Prince Shahu, had her brought to his court in Satara as prisoners of war as a result of the victory over the line in Kolhapur, albeit in honorary custody or house arrest, where the 55-year-old spent the next 15 years in political abstinence before she 1748 made an amazing comeback in old age.

Renewed reign 1749–1761

Battle against the Peshwa 1749–1752

In view of the death of his favorite wife in 1748 and the intrigues in his harem over the succession to the throne, Shahu, who had no male descendant of his own, had allowed Tara Bai to persuade him to adopt a boy, Ramaraja (or Rajaram), as the son of Shivaji II. Or Tara Bais to be adopted and thus recognized as heir to the throne. When Shahu died in 1749 after a long illness, he had already given his young prime minister, the Peshwa Balaji Baji Rao ( Nanasaheb , 1720–1761) extensive powers to the detriment of the heir to the throne out of concern for the future of the country ; Nanasaheb then moved the seat of the Peshwaamt and thus the administrative center of the Maratha State immediately in 1749 to Pune .

How correct this decision was was shown in 1750, when the almost 75-year-old Tara Bai again took over the reign of the marathan state of Satara, this time for the (alleged) grandson she had brought out of anonymity. However, when her creature Rajaram II refused to depose the incumbent Peshwa on a campaign against the Nizam of Hyderabad during his absence , she imprisoned him - like her own son 50 years earlier in 1703 - in the same year and declared him unceremoniously for a fraudster who sneaked their trust.

She accused the Peshwa of wanting to establish a Brahmin rule at the expense of the Kshatriya dynasty. In the two-year struggle with Peshwa Nanasaheb that followed, the almost eighty-year-old finally reached an agreement in 1752 that forced compromises on both sides: in an oath taken on the Marath god Khandoba , Tara Bai solemnly declared the heir to the throne to be a deceiver, but forced the Peshwa to continue his Recognize sovereignty and their own rule. Accordingly, until the end of her life she practiced all activities of a princess in Satara, whereby the Peshwa had to ask her - at least outwardly - for her advice.

Ruler in Satpura 1752–1761

Rajaram II, who was sick and mentally attacked in his imprisonment, was not released from his prison, but remained their prisoner, although as Chatrapati of the House of Bhonsle he remained ruler in name; From now on, however, the real power passed hereditary to their prime minister , so that in addition to Satara, the official seat of the prince, and Kolhapur as the residence of the branch line, there was also the official seat of Peshwa in Pune as a third center of power.

The Marathan generals - the Scindias (Shindes) of Gwalior , the Holkars of Indore , the Gaekwars of Baroda and the Bhonsles of Nagpur - now founded their own principalities, all however under the still valid, nominal suzerainty of the royal house of the Bhonsle of Satara.

Death 1761

Tara Bai died very old at the age of 86, the same year as her hated opponent, Peshwa Nanasaheb from Pune, in the year of the devastating defeat of Panipat in 1761, which left a permanent power vacuum in the north. In her last year in reign, she installed Nanasaheb's second son, Madhav Rao , as the new Peshwa.

The possibilities, but also the limits of the Maratha regional power are reflected in Tara Bai's person and her work, which has spanned almost the entire century since the state was founded in 1674 (Shivaji's coronation). The expansion into the north, which she initiated around 1700, proved to be a failure towards the end of her life.

A loose confederation replaced the originally tight Marathic central government of the founder during her lifetime, but at the same time the Mughal Empire split into regional empires at a breathtaking pace.

Social change in Tara Bai's time

In the decades of wars, society had split up into the actual "marathas", a military service elite on horseback with their own code of conduct, and the agricultural population ( Kunbi ), with robbery and looting being by far the more lucrative activities. Towards the end of Tara Bai's lifetime, the Kunbis therefore also turned to the Maratha soldier's trade. However, when the harvests and thus the tax revenues declined due to the endless war campaigns and threatened the state structure, at the end of Tara Bai's life and reign increasingly mercenaries - Pathans , Arabs , North and South Indians - were used for military service, the term "Marathe" was used one final change.

Due to the need to increasingly reward the troops with cash, the Brahmanic bankers of the west coast ( Kokanasthi - or Chitpavan Brahmins ) also played an important role; They moved from the Konkan (coastal land) to the high Desh (inland), took on more and more political tasks and, as Peshwas, formed the new leadership elite. Linked to this was - despite the Marathic elite's preference for Mughal art and culture - a previously unknown Hinduization and Brahmanization of the entire society.

Live on

Above all , Tara Bai's seven-year struggle for life and death with the troops of Emperor Aurangzeb (1618–1707) makes Tara Bai a popular figure in film, press and on the web to this day for the national and Hindu resistance against Muslims and the Mughal central power, while historians in her see more of an intelligent and determined opportunist with no wider political or religious goals.

Tara Bai counts as the Hindu princesses Chand Bibi (1550-1600) from Ahmednagar , Lakshmibai, Rani from Jhansi (1828-1858) or Ahilya Bai Holkar from Indore (1725-1795), the Christian Begum Samru from Sardhana (1753-1836) or the Muslim Begums of Bhopal , who ruled in uninterrupted women 's lines from 1819 to 1926, were undoubtedly among the "strong women" of India. A comparable curriculum vitae - widowhood, regency, many years of military and diplomatic struggle against relatives and an almost overwhelming central power, denominational and religious special position - can be found in Europe with the Landgrave Amalie von Hessen-Kassel (1602-1651).

Quotes

- "... an adventurer and opportunist ... without consistency and moral principles ... [whose] behavior was inconsistent with her assertions." - Kishore 1963

- "Her case shows that a woman could de facto rule as a wife (or widow) and as the mother (and regent) of a possible heir. To rule as a queen, it took extraordinary talent, energy, and fortune." - Gordon 1993

- "... one of the most remarkable women in Indian history"; Eaton 2005

- "an administrative genius ... an arch triumphant and schemer of the highest order ... she successfully kept Aurangzeb and three Peshwa generations in check"; Mehra 1985

- "People say I'm a quarrelsome woman" - Tarabai 1748

Tara Bai in Folk and Popular Culture

Film adaptations

Representation in non-fiction books and novels

- Manohar Malgonkar: Chhatrapatis of Kolhapur. Popular Prakashan . Bombay: Chand 1971 - Source-oriented non-fiction book in narrative form by the Marathi novelist and novelist Malgonkar (1906–?), Is u. a. excerpts from Eaton, Deccan, pp. 177 ff.

Monuments and statues

- Kolhapur, equestrian statue

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mehra, Dictionary 714

- ↑ Chatrapati , Hindi-Sanskrit-marathi छत्रपति, real "umbrella lord", "ruler with the right to have an umbrella held over him"; Gatzlaff-Hälsig, Concise Dictionary Hindi-German, p. 464.

- ↑ Satara , hindi-marathi satrah (सत्रह) "17", after the seventeen ramparts that surrounded the city; Encyclopaedia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite 2010, sv Satara

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan p. 178

- ↑ Hambir Rao's sister Soyarabai († 1681) was one of the wives of the state founder Shivaji since 1659 and gave birth to his son Rajaram, who later became heir to the throne and Tara Bai's husband.

- ↑ The other legitimate wives were Janki Bai, also daughter of a senapati (general) of the founder of the state and father-in-law Shivaji, also Rajas Bai and Ambika Bai; there was also a concubine, the mother of Karna , who was briefly raised to Gaddi ; Mehra, Dictionary p. 714; Gordon, Marathas p. 101

- ↑ Duff I, 327 f.

- ↑ Mehra, Dictionary p. 714; Sarkar, Short History p. 335

- ↑ Malleson, Historical Sketch, p. 255, names Sambhajis as the date of death and Raja Ram's reign of 1695, as his date of death 1698

- ↑ So most recently Gordon, Marathas 1993, S.Khafi Khan reports, however, of two children together; quoted according to Eliot-Dowson, History of India, Vol. 7, p. 409: "Tara Bai was widow of Ram Raja, that is, she was the widow of the uncle of Raja Shahu, and Ram Raja left two sons by her of tender years. "

- ↑ Mehra, Dictionary p. 717; Sarkar, Short History p. 337

- ↑ Khafi Khan, cit. after Eliot-Dowson, History of India, Vol. 7, p. 367; Mehra, Dictionary, p. 714; Eaton, Deccan 182

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, p. 180.

- ↑ Mehra, Dictionary, p. 714.

- ^ Eaton, Deccan, p. 182.

- ↑ Richards, Mughal Empire, p. 234; Eaton, Deccan, p. 181.

- ^ Gordon, Marathas, p. 101; Eaton, Deccan, p. 181.

- ↑ Gordon, Marathas, p. 101 and Eaton, Deccan, p. 181 f. do not mention this son and his accession to the throne

- ↑ On the Upanayana ceremony, especially for Kshatriyas , see Jean Antoine Dubois , Life and Rites of the Indians, Part II, Chap. 1, pp. 150–157, v. a. P. 156 f.

- ^ Sarkar, Short History, p. 332; Richards, Mughal Empire, p. 234 with reference to Sarkar, History of Aurangzeb, vol. V, p. 136.

- ↑ See Map 5 in Gordon, Marathas, p. 102

- ^ Richards, Mughal Empire, p. 238; Eaton, Deccan, p. 183.

- ↑ Jadunath Sarkar, A Short History of Aurangzib, p. 337; also Sarkar, Rise of the Maratha Power , p. 28

- ^ Malleson, Historical Sketch, p. 255.

- ↑ Khafi Khan, cit. after Eliot-Dowson, History of India, Vol. 7, p. 367; Life data according to Eaton, Deccan, p. 177.

- ↑ Richards, Mughal Empire, p. 259.

- ↑ Malleson, Historical Sketch p. 255; Sarkar, Short History p. 338 f.

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, p. 184; his mother, Yesu Bai, was not released until 1718 and may have served as a hostage.

- ↑ On the way back Shahu had paid another visit to the emperor's tomb in Khuldabad ; Gordon, Marathas, p. 103; Eaton, Deccan 184

- ↑ Title and office of Peshwa, personal "leader", goes back to the model of the Bahmani Sultanate and the subsequent Dekkan Sultanates of Bijapur and Ahmednagar . The Peshwa usually presided over a ministerial "Council of Eight"; Eaton, Deccan, p. 185.

- ↑ Kolhapur continued to exist as a British princely state until Indian independence in 1947, while Satara became part of British India in 1848. There were two other lines of the Bhonsle dynasty: the Bhonsle of Nagpur and of Thanjavur .

- ^ Gordon, Marathas, p. 105; Richards, Mughal Empire, p. 259.

- ↑ Description in Gordon, Marathas, p. 106

- ^ Genealogy of the Bhonsle Dynasty of Kolhapur

- ↑ When Sambhaji II died in 1760 without an heir, the house of the state's founder, Shivaji Bhonsle, had died out in the male line; his mother Rajas Bai then adopted an alleged great-grandson of Shivaji's chosen by herself and led the government as regent until her death in 1772; Malleson, Historical Sketch, p. 256; Aberigh-Mackay, Native Chiefs, pp. 70 f.

- ↑ Tara Bai could choose between imprisonment in the Panhala fortress or at the court in Satara; Eaton, Deccan, p. 195.

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, p. 186 f., P. 187 erroneously names 34 instead of 19 years imprisonment, from 1730.

- ↑ The procedure of adopting a distant relative was not unusual in principle and was used by Sayaji Rao Gaedwad III in 1875 . , applied to the Marathas of Baroda; engl. wiki

- ↑ It was not until 1763, two years after Tara Bai's death, that Rajaram II was released and placed on the throne; Mehra, Dictionary p. 716

- ↑ Duff, History, Bd.I, S. 412th

- ↑ Kulke / Leue / Lütt / Rothermund, Indian History (Literature Report) 1982, p. 228.

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, pp. 187ff., 190 f.

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, pp. 193 f.

- ↑ Eaton, Deccan, p. 192 f.

- ↑ Mehra, Dictionary

- ↑ Kishore quoted. after Mehra, Dictionary, p. 715, translated from English

- ^ Gordon, Marathas, p. 160, translated from English

- ^ Eaton, Deccan, p. 177.

- ↑ Quotes from Mehra, Dictionary p. 716, translated from English

- ↑ Quoted in Eaton, Deccan, p. 177, after Malgonkar, Chhatrapatis of Kolhapur 1971, p. 181, translated from English

literature

Secondary literature

- Richard M. Eaton: A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761 . Cambridge et al. a. : CUP 2005. (The New Cambridge History of India I, 8) - Darin pp. 177-202 Tarabai (1675-1761): the rise of the Brahmins in politics .

- John F. Richards: The Mughal Empire . Cambridge et al. a. : CUP 1993. (The New Cambridge History of India I, 5) - reprinted 2000

- Sushila Vaidya: Role of women in Maratha politics (1620 - 1752 AD) . Delhi: Sharada 2000. - Part. zugl. Univ. Diss. Saugar (Sagar), MP

- MS Naranave: Forts of Maharashtra . New Delhi 1995.

- Stuart Gordon: The Marathas, 1600-1818 . Cambridge et al. a. : CUP 1993 (The New Cambridge History of India II.4), v. as100 ff.

- Shalini V. [asantrao] Patil: Maharani Tarabai of Kolhapur (c.1675-1761 AD) . New Delhi 1987. - Part. zugl. Bombay Univ. Diss.

- Parshotam Mehra: A Dictionary of Modern Indian History 1707-1947 . 2nd edition Delhi. Bombay. Calcutta. Madras: Oxford University Press 1987. - pp. 714-716 sv Tara Bai

- V. [iṭhṭhala] G. [opāla] Khobarekara (ed.): Tarikh-i-Dilkasha (Memoirs of Bhimsen Relating to Aurangzib's Deccan Campaign) , obs.v. Jadunath Sarkar. Bombay: Dept. of Archives 1972. (Sir Jadunath Sarkar birth centenary commemoration volume)

- Appasaheb Ganapatrao Pawar: Tarabai papers. A collection of Persian letters, with photographs of 212 letters, copied from originals; summarized into English and Marathi. Foreword by Sethu Madhava Rao Pogdi. English and Marathi index. 216 pp. Kolhapur: Shivaji University Press 1971. - Text in Persian. According to the preface, the collection of letters was put together by Govindrao Prabhu.

- Appasaheb G. [anapatrao] Pawar (ed.): Tarabai Kalina Kagada Patre . 3 vols. Kolhapur 1969. (Kolhapur Documents Relating to the Tarabai Period)

- Brij Kishore: Tara Bai and her Times . London. Bombay: Asia Publication House 1963

- Govind Sakharam Sardesai : New History of the Marathas . 3 Vols. Vol. 1: Shivaji and his line 1660-1707 (1946); Vol. 2: The Expansion of the Maratha power 1707-1772 (1948); Vol. 3: Sunset over Maharashtra 1772-1848 (1948). Bombay: Karnatak Printing Press et al. a. 1946-1948 (several reprints).

- Jadunath Sarkar : History of Aurangzib, mainly based on Persian sources . 5 vols Calcutta: Sarkar 1912-1924 (1958)

-

Jadunath Sarkar : History of Aurangzib, mainly based on Persian [later: Original] sources . Calcutta: Sarkar 1912-1924.

- 1. Reign of Shah Jahan . 1912 digitized volume 1

- 2. War of succession . 1912 digitized volume 2

- 3. First half of the reign, 1658-1681 . 1916 - 2nd minor supplementary edition 1921. 3rd again slightly supplementary edition 1928 digitized volume 3

- 4. Southern India, 1645-89 . 1920. - 2nd exp. and partly rewritten edition 1929 digitized volume 4

- 5. The closing years, 1689-1707 . 1924 digitized volume 5

- Jadunath Sarkar : Rise of the Maratha Power (1630-1707) . In: Maharastra State Gazetteers. History. Part III - Maratha Period . Bombay: Govt. Printing 1967, pp. 1-29

- Vishvanath Govind Dighe: Peshwa Baji Rao I and Maratha Expansion. Bombay: Karnatak Publ. House 1944. (Zugl. Bombay Univ. Diss. 1941)

Sources and older authors

- George R Obert Aberigh-Mackay: The Native Chiefs and their States in 1877. A Manual of Reference. Second edition, with index. Bombay: The Times 1878.

- GB Malleson: An historical sketch of the native states of India . London: Longmans, Green & Co. 1875 (digitized)

- James Grant Duff [former political resident in Satara]: A History of the Mahrattas. With copious notes . 3 vols. London: Longman u. a. 1826 online version .

- Khafi Khan: Muntakhab-ul Lubab . In: Henry Miers Elliot . John Dowson : The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammedan Period. Vol.7: From Shah Jahan to the Early Years of the Reign of Muhammad Shah . London: Trübner 1867–1877. - "... the great work of Khafi Khan, a contemporary history of high and well-deserved repute"; ibid Sv and pp. 207-210. Online version

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tara Bai |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | ताराबाई (hindi, marathi); Rani Tara Bai; Tarabai; Tara bye; Sita Bai (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Regent in the Marathas Empire in northwest India |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1675 |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 9, 1761 |

| Place of death | Satara , today: Maharashtra |