Winery I

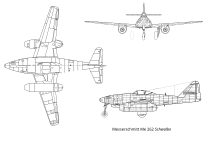

Weingut I (coll. Bunker area ) was the code name for a project started in 1944 to build a semi-underground armaments bunker for the production of the Messerschmitt Me 262 , the first series-built military aircraft with jet engines . The planned facility was located in Mühldorfer Hart in the Upper Bavarian district of Mühldorf . After completion, Weingut I was supposed to ensure the production of the aircraft, which was regarded as decisive for the war, together with five other protected production facilities in the area around Landsberg am Lech (camouflage name Weingut III in today's Welfen barracks ), in the Sudetenland and in the Rhineland . The facility was only partially completed and never used for its intended purpose.

background

In preparation for the invasion of Normandy , the Allies focused the aerial warfare against Germany from early 1944 on primarily on destroying the German Air Force . Planning for the so-called Big Week had been in progress since 1943 , during which the German production of fighter planes was to be permanently destroyed through targeted air strikes on final assembly plants. Between February 20 and 25, nearly 10,000 American and British aircraft, including around 6,000 bombers, attacked strategic targets across Germany. As a result of these attacks, which caused severe damage to German aircraft production, the production quota decreased enormously. In response, the so-called Jägerstab was founded in March 1944 . Its task was to contribute to the maintenance and increase of the production of fighter aircraft. He replaced the Ministry of Aviation in his responsibility. At the head of the Jägerstab were Armaments Minister Albert Speer , Deputy State Secretary in the Aviation Ministry Erhard Milch and Chief of Staff Karl Saur . The plan of the Jägerstab was to protect the aircraft industry, especially the manufacture of the Messerschmitt Me 262 , to accommodate them in bunkered production facilities. However, the plan was not entirely new; a similar project was already considered in October 1943, but not implemented. The new plan initially provided for six locations at which (semi) underground bunkers were to be built, originally designed for a minimum size of 600,000 to 800,000 m² each. But just two weeks later, at the Jägerstab meeting on March 17, 1944, the size of the building projects had dropped to 60,000 m² each. Due to the Allied invasion in June 1944, the focus was finally on two locations in Upper Bavaria . Three bunkers were to be built under the code name "Ringeltaube" near Kaufering in the Landsberg am Lech district . The planned hunter factory in Mühldorfer Hart had the code name "Weingut I". According to Franz Xaver Dorsch , who was responsible for the construction , a hunter factory should, at best, be ready in five to six months. Speer later wrote in his memoir that even then it was not difficult to predict that the projects would not be completed within the planned six months.

The location near Mühldorf met all the necessary requirements. There was a sufficient layer of gravel on the lower terrace of the Inn, and the water table was also sufficiently deep. The location at the Mühldorf railway junction was strategically advantageous. The extensive forest area also offered good camouflage opportunities.

Building organization

The planning and organization of the construction project was the responsibility of the chief construction office of Organization Todt (OT) in Berlin and thus Ministerialrat Franz Xaver Dorsch, Speer's deputy in the OT. The OT Task Force Germany VI supervised the construction project on site with offices in Ampfing , Mettenheim and Ecksberg near Mühldorf . The chief construction manager at OT was the architect Bruno Hofmann. The technical construction work was entrusted to Polensky & Zöllner (P & Z). In addition, other companies worked on the project as subcontractors . The company P & Z was already involved in the construction of the Inn Canal in the Mühldorf area in the 1920s . Almost 200 employees of the company were sent to Mühldorf for the construction project, where they worked as the Polensky & Zöllner OT unit , construction team 773 . P&Z site manager on the construction site was the engineer Karl Gickeleiter. The construction costs were put at almost 26 million Reichsmarks , which today corresponds to around 100 million EUR.

Manpower

For the construction project, the P&Z company provided a total of 200 of its own workers, as well as 800 to 1,000 workers from its affiliated Soviet companies and 200 to 300 Italian workers. However, this maximum of 1,500 workers was by no means sufficient to implement the planned projects promptly. Therefore, thousands of forced laborers were used. The majority of them were prisoners from the Mühldorf concentration camp complex . The OT set up other forced labor camps in Mühldorfer Hart, Ampfing, Mettenheim and Ecksberg. The forced laborers also included a large number of Soviet prisoners of war . In total, well over 10,000 workers were working on the construction site of the Weingut I project. On the main construction site, work was usually carried out in two shifts of 4,000 men each.

P&Z documents show that prisoners of war worked a total of 322,513 hours, and concentration camp inmates 2,831,974 hours. The SS and OT billed the company 1,892,656.20 Reichsmarks for this forced labor.

construction

Building preparations

Adolf Hitler's order of April 21, 1944 officially paved the way for construction work to begin. First of all, the land required for the construction project was confiscated, with no compensation paid. From mid-May, the OT set up in the Ecksberg asylum, which was also confiscated for this purpose, and built a first barrack camp. Then the required machines and objects were gradually delivered to Mühldorf, including a large number of large machines. The equipment had to be organized from all over the Reich and the occupied territories, which, given the military situation on the fronts, was an extremely complicated undertaking. Concrete works, a carpentry shop, a gravel sorting plant and other ancillary facilities also had to be set up in the Ampfing / Mettenheim area. In addition, several bunkers - to protect against attacks from the air - were built before the actual construction work began on the main construction site. For the transport of material, the Reichsbahn set up a network of industrial track systems , which was connected to the Munich – Mühldorf railway line .

In view of the size of the construction project, it was hardly possible to camouflage the project effectively, especially from enemy aerial reconnaissance. Efforts to do this were therefore not too thorough. The individual components were painted green, and when a construction section was completed, it was planted with bushes and trees or covered with camouflage nets . A dummy construction site had even been erected between Burghausen and Altötting in order to deceive the Allies' aerial reconnaissance. Although there were air raids in the immediate vicinity on the air base in Mettenheim and the railway area in Mühldorf, the bunker area itself was never bombed. Today there is disagreement about the reasons. One possibility is mentioned that the Allies did not suspect such projects in the more agrarian Mühldorf, i.e. did not specifically look for them. Another reason could be that they knew about the existence of the forced labor camps and did not want to run the risk of hitting the camps if the armaments plant was bombed. If the Allies were aware of the construction project, other bomb targets are likely to have had a higher priority, as the completion of Weingut I had become unlikely.

Construction work

The actual construction work on Weingut I began in July 1944. The plans envisaged a bunker consisting of twelve arches , which would extend over a length of 400 m in an east-west direction. At the bottom it was laid out to a width of 85 m. The interior height was planned to be 32.2 m, 19.2 m below the ground level. The arches reached a thickness of three meters, which was later to be reinforced by a further layer of concrete to a total of five meters.

A simple and effective new method was used to build the bunker. A so-called extraction tunnel was first built along the entire length of the planned bunker, which was equipped with silo locks and rails and was located below the ground level. In the next construction phase, the foundation was built, which reached a thickness of up to 17 m and should serve as an abutment . The gravel excavated in the process then served as part of the formwork core for the vault that was now to be built. After completing a vault, the formwork began to be removed. The extraction tunnel built in advance was used for this purpose. When the silo locks were opened, the gravel ran into the transport trucks below and was then transported away. The tunnel was then dismantled and excavators continued to excavate until the bottom was 19.2 m deep. With this method, one arch after the other - starting from the east - was built. The interior of the bunker was designed for up to eight floors, but was only started on the first arch. By the end of April 1945, only seven of the twelve planned external vaults had been completed. In the last months of the war it was simply no longer possible to procure enough material and manpower to keep to the schedule.

Degradation and destruction

When the 47th US tank battalion of the 14th Division reached the Mühldorf district in early May 1945, the area, including all ancillary facilities, was placed under US military administration. The technical equipment was still allowed to be dismantled by the companies, and the Reichsbahn also removed the track systems belonging to the complex. Initially, the Americans pursued the plan to use the bunker facilities as a test site for bombing to test the resistance of the construction and the effectiveness of their bombs. This project was finally rejected and in the summer of 1947 the demolition of the facility was ordered. Only after several attempts at blasting could six out of seven arches be blown up using 120 tons of TNT . The ruins of the bunker can still be seen in the forest near Mettenheim today, although companies from the area continued to use a lot of material for other construction projects in the following years. The area came into the public eye when rumors arose in the early 1980s that after the end of the war warfare agents of the Wehrmacht were being stored in the longitudinal tunnels of the bunker foundation. This was only confirmed by the authorities in 1987; the weapons, including the warfare agent CLARK 1 , were then disposed of.

Concentration camp memorial

The bunker area was included in the Bavarian list of monuments as a memorial to the atrocities of the Nazi era , but despite many protests, air raid bunkers in the area of the main bunker began to be razed in 1995. The Katholisches Kreisbildungswerk Mühldorf and the working group "For Remembrance" campaigned for the respectful handling of the bunker area and the former concentration camps.

To commemorate the suffering of the prisoners and the dead buried in the surrounding concentration camp cemeteries, a three-part concentration camp memorial was opened in Mühldorfer Hart in April 2018.

Court process

After the war, the war crimes in connection with the armaments project and the concentration camps / forced labor camps were tried in several trials before the American military court in Dachau, including the so-called Mühldorf trial . Among the defendants were members of the management of Polensky & Zöllner (including Karl Bachmann, director of the Munich branch of P & Z, Karl Gickeleiter, site manager of the main construction site and foreman Otto Sperling). The verdict was pronounced on May 13, 1947. The charges against Karl Bachmann were dropped because they could not prove that he was involved in the work of the prisoners. Gickeleiter was sentenced to 20 years in prison; the sentence was reduced to ten years in 1951 before the early release on July 19, 1952. Sperling's death sentence was shortly commuted to life imprisonment and later reduced again before he was finally released on July 20, 1957.

Picture gallery

literature

- Hansgeorg Bankel : A German War Plant from 1944/45: The Aircraft Factory Weingut I and the Concentration Camp Waldlager 6 near Mühldorf / Inn . In: Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Construction History , Cottbus, May 2009, Vol. 1, 107-118.

- Hansgeorg Bankel: Building history studies on an armaments complex from the last year of the war 1944/45. The semi-subterranean aircraft factory hall and the concentration camp forest camp V / VI near Mühldorf am Inn , in: I. Scheuermann (Ed.): Memories Mapping? Recording of building findings in memorials (Dresden 2012), pp. 52–55.

- Elke Egger: The district of Mühldorf a. Inn under National Socialism . Rhombos-Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-930894-39-4 .

- Peter Müller: The bunker area in Mühldorfer Hart: armaments mania and human suffering . 4th edition. Heimatbund; Mühldorf a. Inn: District Museum, Mühldorf a. Inn 2006, ISBN 3-930033-17-8 .

- Edith Raim: The Dachau concentration camp external commandos Kaufering and Mühldorf - armaments buildings and forced labor in the last year of the war 1944–1945 . Dissertation, Landsberg 1992.

Web links

- Mühldorf history workshop about the Mühldorf district in the Nazi era

- Working group "For remembering"

- 360 ° “Panorama Tour” - Mühldorfer Hart bunker area

- Winery I on LostAreas

Coordinates: 48 ° 14 '25.4 " N , 12 ° 27' 9.6" E

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Peter Müller: The bunker area in Mühldorfer Hart: Armaments mania and human suffering . 4th edition. Heimatbund; Mühldorf a. Inn: District Museum, Mühldorf a. Inn 2006, p. 11 f.

- ↑ Edith Raim: The Dachau KZ external commandos Kaufering and Mühldorf - armaments buildings and forced labor in the last year of the war 1944–1945 . Dissertation, Landsberg 1992, p. 46.

- ↑ Minutes of the leaders' meeting of March 5, 1944, Bundesarchiv Koblenz, R 3/1509, p. 12.

- ↑ Minutes of the Jägerstab meeting of March 17, 1944, Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv, RL 3/2, p. 677.

- ↑ Raim (1992), p. 43.

- ↑ "Nevertheless it was not so difficult to predict that these six huge bunker works would not be finished in the promised six months, yes that they could no longer be put into operation at all." From Albert Speer: Memories . 9th edition, Frankfurt am Main 1971, p. 348.

- ↑ For the entire paragraph: Raim (1992), pp. 28 ff.

- ↑ a b Letter from A. Hitler to A. Speer (April 21, 1944), Bundesarchiv Koblenz, R 3/1576, p. 131: “I instruct the head of the OT headquarters, Ministerialdirektor Dorsch, while maintaining his other functions within your scope Area of responsibility with the execution of the six hunter structures ordered by me. "

- ↑ a b Müller (2006), p. 14.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 13.

- ↑ This figure was based on the template: Inflation determined, has been rounded to the nearest million and relates to January 2020.

- ↑ Raim (1992), p. 109.

- ^ Statement by the accountant von Polensky & Zöllner (Johann Häuschen) in the Mühldorf trial, microfilm 123a / 4, p. 139 ff., Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv München.

- ↑ Raim (1992), p. 112.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 17.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 18.

- ↑ Raim (1992), pp. 136-138.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 18 f.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 20 ff.

- ↑ History workshop Mühldorf (ed.): The bunker area in Mühldorfer Hart - the facts - the victims - the perpetrators . History workshop, Mühldorf 1999, p. 2.

- ↑ Müller (2006), p. 29 ff.

- ^ Matthias Köpf The Forgotten Camp , Süddeutsche Zeitung, April 3, 2018, p. 32

- ↑ United States Army Investigation and Trial Records of War Criminals - United States of America v. Franz Auer et al. November 1943-July 1958, National Archives and Records Administration. (Available online as PDF; 0.9 MB)