Winter depression

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F33.0 or F33.1 |

Recurrent depressive disorder, currently mild or moderate episode |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The winter depression is a depressive disorder that occurs in the autumn and winter months. As a special form of affective disorders , it is assigned to recurrent depressive disorders in the ICD-10 .

It is a manifestation of the seasonal affective disorder (also SAD from Seasonal Affective Disorder; emotional disorder depending on the season), to which other symptoms that are fundamentally characteristic of depression such as changed mood, reduced energy level, anxiety, prolonged sleep, increased An appetite for sweets (carbohydrate cravings) and weight gain are counted as symptoms atypical for depression. In contrast, seasonal independent depression is more likely to experience loss of appetite, weight loss and shortened sleep.

Winter depression was first described and named by Norman E. Rosenthal and colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health in 1984.

causes

Disturbances of the daily biological rhythm are assumed to be one of the causes . There are different assumptions about this . One says that the symptoms of SAD patients are related to the serotonin - melatonin metabolism. Incidence of light on the retina acts as a timer by causing more melanopsin to form there. The short-wave (blue-accentuated) light that predominates at noon has a strong effect, while the rather long-wave (red-accentuated) light at dusk has little effect. Under the influence of melanopsin, special photosensitive ganglion cells send signals to the brain , which then adjusts the organism's internal clock to daily activity. There are many serotonin-producing cells in the pineal gland (epiphysis) of the human brain. As part of the daytime activation, these cells increasingly release serotonin, which can have a mood-enhancing effect. In contrast, the formation of melatonin from tryptophan and serotonin is inhibited by light stimuli reaching the retina of the eye, so that the melatonin concentration in the brain is low during the day, but increases several times over at night, with a maximum around three in the morning. It is controversial whether melatonin induces depression, but it is recognized that it increases the need for sleep. This daily ( circadian ) rhythm is superimposed on a seasonal (seasonal ) rhythm with increasing distance from the tropics : In winter, the longer dark phases in the higher latitudes compared to summer lead to generally reduced serotonin and increased melatonin values. This results in seasonal (winter) depression in some people. The symptoms of winter depression, which deviate from the non-seasonal depression (increased tendency to sleep, increased appetite) can therefore be explained by a reduced serotonin and increased melatonin production during the day.

Some scientists argue that these seasonal fluctuations originally had no disease value, but on the contrary could have had an important role in the survival of the group. According to this theory, the fact that the organism reacts to the shorter days by conserving its own resources (e.g. through increased sleep) and weight gain was an advantage of vital importance to survival. This mechanism only became problematic in modern western society, in which resources are available in abundance at all times of the year and activity is required regardless of the season.

treatment

As with all diseases, causal therapy should first be attempted (i.e., eliminate the pathogenic cause or at least strive to do so).

Causal treatment

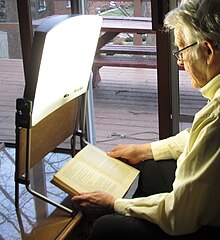

By restoring the timers for the production of serotonin and melatonin, winter depression can be counteracted. Therefore, it makes sense to have enough light in the early morning. As part of light therapy , just a few hundred lux incidence of light on the retina is sufficient for one to two hours before 6 am (“at dusk”). At a distance of the eyes from the light source of about one meter, a light source produces today commercially available high energy efficiency , for example in LED - or "energy saving lamps" already with less than 10 watts of power consumption a luminous flux (lumen) which causes such a light onto the retina . In interiors with normal lighting, on the other hand, the incidence of light on the retina is often below 100 lux. If the incidence of light does not occur until later in the morning, an incidence of light of several thousand lux is obviously required to brighten the mood. On a summer day, however, the illuminance in the open air is around 100,000 lux. To make the transition to sleep easier, avoid too much light in the evening . The direct administration of serotonin is ruled out as a measure against winter depression because it can not cross the blood-brain barrier .

The current treatment guideline recommends light therapy for depression that follows a seasonal pattern. About 60-90% of patients benefited from light therapy after about two to three weeks. The IGeL monitor of the MDS ( Medical Service of the Central Association of Health Insurance Funds ) rates light therapy for seasonal depressive disorders as “generally positive” . The light therapy could alleviate the depressive symptoms somewhat better than a sham treatment, according to the test portal that analyzed the study. Although the investigations and reviews found did not show a uniform picture of the benefits of light therapy, they did show indications of a minor benefit. The light radiation no longer contains any UV, so it is harmless. Damage such as headaches, tiredness and similar complaints did not occur more frequently than with sham treatment. However, a walk in the light of day can be just as helpful, which is why light therapy is not a service provided by the statutory health insurance companies ( economic efficiency requirement ). The evaluation of the IGeL-Monitor was based primarily on a US review article as well as on guidelines from the British health system

The organisms on earth have adapted to changes in the length of the day and have developed corresponding circadian internal clocks in order to set activities, reproduction and metabolic processes at biologically advantageous times. It is not yet clear whether a disturbed circadian system is causing the depression or whether the depression is the cause of the changed circadian system or whether other combinations are responsible. At least influences on this circadian system could also lead to therapies against seasonal depression. For example, sleep deprivation or lithium can influence such circadian systems and also treat depression.

Effective light colors:

| red | + | green | = | yellow | ||

| green | + | blue | = | Cyan | ||

| red | + | blue | = | magenta | ||

| red | + | green | + | blue | = | White |

It is not enough with white light, since it can be mixed from red, green and blue spectral lines as well as from yellow and blue emission lines alone . That is why it was checked which wavelengths of light ( light colors ) would have an influence on light therapy. Light with short or medium wavelengths (blue, green, yellow) seem to be necessary for a therapeutic effect, red light and UV light would be relatively ineffective, UV light can therefore be filtered out.

Symptomatic treatment

If a causal treatment is not possible, the symptoms can be treated with antidepressants , such as B. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors , serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors or atypical antidepressants such as the selective noradrenaline - dopamine reuptake inhibitor bupropion . In the S3 guideline / NVL Unipolar Depression Treatment 2015 , medication with SSRIs, in addition to light therapy, is the first choice for the treatment of seasonal depressive disorders.

In herbal medicine , for example, St. John's wort is used to alleviate the symptoms of winter depression.

history

Winter depression was already described by Hippocrates and Aretaios in antiquity .

literature

- SJ Lurie, B. Gawinski, D. Pierce, SJ Rousseau: Seasonal affective disorder. In: Am Fam Physician. 2006 Nov 1; 74 (9), pp. 1521-1524. Review. PMID 17111890

- E. Pjrek, D. Winkler, S. Kasper: Pharmacotherapy of seasonal affective disorder. In: CNS Spectr. 2005 Aug; 10 (8), pp. 664-669; Review. PMID 16041297

- CH Sohn, RW Lam: Update on the biology of seasonal affective disorder. In: CNS Spectr. 2005 Aug; 10 (8), pp. 635-646. Review. PMID 16041295

- RW Lam, RD Levitan: Pathophysiology of seasonal affective disorder: a review. In: J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2000 Nov; 25 (5), pp. 469-480. Review. PMID 11109298

- Joachim Fisch: Light and Health - Life with Optical Radiation. Literature research: compilation, results and outlook, period: 1800–2000. (PDF) TU Ilmenau 2000, research on behalf of the mechanical engineering and metal professional association

Individual evidence

- ↑ Timo Partonen, SR Pandi-Perumal: Seasonal Affective Disorder: Practice and Research ; OUP Oxford, 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-954428-8 .

- ↑ C. Simhandl, K. Mitterwachauer: Depression and Mania. Vienna 2007, p. 35.

- ^ NE Rosenthal, DA Sack, JC Gillin, AJ Lewy, FK Goodwin, Y. Davenport, PS Mueller, DA Newsome, TA Wehr: Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy . In: Archives of General Psychiatry , 41 (1), 1984, pp. 72-80, doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.1984.01790120076010 , PMID 6581756 .

- ^ Fiona Marshall, Peter Cheevers: Positive options for Seasonal Affective Disorder , p. 77. Hunter House , Alameda CA 2003, ISBN 0-89793-413-X .

- ↑ a b c Wolfgang Engelmann: Lithium ions against depression: Is the daily clock involved in endogenous depression? Experiments on Svalbard ; Publication of the University of Tübingen, Tübingen, December 2010, PDF file (PDF)

- ↑ a b c Lydia Klöckner: Lack of light - "We are in energy-saving mode". Zeit online , November 5, 2012; Interview with Dieter Kunz.

- ^ J. Kalbitzer, U. Kalbitzer, GM Knudsen, P. Cumming, A. Heinz: How the cerebral serotonin homeostasis predicts environmental changes: a model to explain seasonal changes of brain 5-HTT as intermediate phenotype of the 5-HTTLPR. In: Psychopharmacology . Volume 230, Number 3, December 2013, pp. 333-343.

- ↑ David H. Avery et al. a .: Dawn simulation and bright light in the treatment of SAD: a controlled study. In: Biological Psychiatry. Vol. 50, No. 3, August 1, 2001, pp. 205-216. doi: 10.1016 / S0006-3223 (01) 01200-8 Abstract

- ↑ RN Golden u. a .: The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. In: Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162, pp. 656-662, PMID 15800134 .

- ↑ Online calculator for the relationship between luminous flux, distance, beam angle and resulting illuminance (commercial website)

- ↑ A. Wirz-Justice et al. a .: Dose relationships of morning bright white light in seasonal affective disorders (SAD). In: Experientia. May 15, 1987, Vol. 43, Vol. 5, pp. 574-576. [1] (PDF file)

- ↑ S3 guideline on unipolar depression. (PDF) Retrieved February 21, 2019 .

- ↑ SH Kennedy, RW Lam, NL Cohen, AV. Ravindran: Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. In: Can J Psychiatry . IV. Medications and other biological treatments , 46 Suppl 1, 2001, p. 38S-58S .

- ↑ Light therapy for seasonal depressive disorder ("winter depression") . IGeL monitor; accessed on February 15, 2019. More on the justification for the assessment in the results report . (PDF) accessed on February 15, 2019.

- ↑ How light therapy helps against winter blues . Jameda, December 9, 2016. Medien-Doktor: Research tip: IGeL-Monitor takes stock after five years: Usually more harm than good . February 16, 2017. Test report: Doctors cash in with nonsense, Part 9: Positive tendency: Light therapy for winter depression . Spiegel Online , January 25, 2012

- ^ RN Golden et al .: The efficacy of light therapy in the treatment of mood disorders: a review and meta-analysis of evidence . In: Am J Psychiatry , 2005, 162 (4), pp. 656-662, PMID 15800134 .

- ↑ depression. The treatment and management of depression in adults . NICE guideline, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009.

- ↑ Mendels, J.: Lithium in the treatment of depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 1976, 133 (4), pp. 373-378.

- ↑ PC Baastrupa, JC Poulsen, M. Schoub, K. Thomsen, A. Amdisen: [Prophylactic Lithium: Double blind discontinuation in manic-depressive and recurrent-depressive disorders] , The Lancet, Vol. 296, No. 7668, 15. August 1970, pages 326-330

- ↑ TMC Lee, CCH Chan, JG Paterson, HL Janzen, CA Blashko: Spectral properties of phototherapy for seasonal affective disorder: a meta-analvsis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, Vol. 96, No. 2, August 1997, pages 117-121

- ↑ S3 guideline / NVL Unipolar Depression Treatment 2015 ( Memento from September 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF file)

- ^ J. Sarris, A. Panossian, I. Schweitzer, C. Stough, A. Scholey: Herbal medicine for depression, anxiety and insomnia: a review of psychopharmacology and clinical evidence. In: European Neuropsychopharmacology . Volume 21, Number 12, December 2011, pp. 841-860, ISSN 1873-7862 . doi: 10.1016 / j.euroneuro.2011.04.002 . PMID 21601431 .

- ↑ M. Yildiz, S. Batmaz, E. Songur, ET Oral: State of the art psychopharmacological treatment options in seasonal affective disorder. In: Psychiatria Danubina. Volume 28, Number 1, March 2016, pp. 25-29, PMID 26938817 (review).