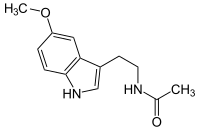

Melatonin

| Structural formula | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||

| Surname | Melatonin | ||||||||||||||||||

| other names |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Molecular formula | C 13 H 16 N 2 O 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Brief description |

beige solid |

||||||||||||||||||

| External identifiers / databases | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Drug information | |||||||||||||||||||

| ATC code | |||||||||||||||||||

| Drug class | |||||||||||||||||||

| Mechanism of action |

Replacement of the naturally insufficiently produced hormone |

||||||||||||||||||

| properties | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molar mass | 232.28 g mol −1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Physical state |

firmly |

||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point |

117 ° C |

||||||||||||||||||

| solubility | |||||||||||||||||||

| safety instructions | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Toxicological data | |||||||||||||||||||

| As far as possible and customary, SI units are used. Unless otherwise noted, the data given apply to standard conditions . | |||||||||||||||||||

Melatonin is a hormone that is produced from serotonin by the pinealocytes in the pineal gland (epiphysis) - part of the diencephalon - and controls the day-night rhythm of the human body.

physiology

General

Melatonin is a metabolite of the tryptophan metabolism. Its formation is controlled in the brain in the pineal gland (epiphysis) by the circadian pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic core and is inhibited by light. When it is dark in the biological night , this inhibition is lifted, production increases and with it the secretion of melatonin. Other places of production in the body are the intestines and the retina of the eye. The melatonin concentration increases during the night by a factor of three (in older people) to twelve (in young people), the maximum is reached around three o'clock in the morning - with a seasonally changing rhythm. The secretion is slowed down by daylight. The role of melatonin in jet lag and shift work is generally recognized, but the use of melatonin in this context is controversial. By coordinating the circadian-rhythmic processes in the body, it unfolds its effect as a timer. The melatonin- induced deep sleep phase stimulates the release of the growth hormone somatropin . Corresponding chronic disorders lead to premature somatopause . Other important melatonin effects are its action as an antioxidant . The antigonadotropic effect (reduction in size of the sex glands ) and the downregulation of many biological and oxidative processes are also important, which is particularly important when taking melatonin. A decrease (but also an increase) in the melatonin level in the blood causes sleep disorders or disorders of the sleep-wake rhythm.

biosynthesis

The biosynthesis is carried out serotonin selected from the amino acid tryptophan is obtained in two steps: first serotonin with acetyl coenzyme A N -acetyliert as catalyst affects the enzyme serotonin N -acetyltransferase (AANAT). Then the product is N -Acetylserotonin with S -Adenosylmethionin means of Acetylserotonin- O -methyltransferase methylated . The first step is rate-limiting, and the activity of its enzyme is indirectly regulated by daylight.

Dismantling

After passage through the liver, 90% of melatonin is metabolized to 6-OH-melatonin by biotransformation using cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and excreted in the urine in the form of sulfated (60–70%) or glucuronidated (20–30%) derivatives .

Melatonin deficit

No uniform definition of deficit has yet been established for melatonin. This is all the more astonishing as it is used therapeutically on a large scale (see below). While there are corresponding concentration data for other hormones, which can be used to orientate yourself whether a hormone substitution, i.e. a replacement of something missing, is necessary (see Addison's disease ), these are completely absent with melatonin.

In addition to large inter-individual differences, the circadian darkness-dependent synthesis of melatonin also makes it difficult to establish routine laboratory values easily.

However, a high degree of epiphyseal calcification can be regarded as an indication of an individual melatonin deficiency. The first evidence can be found in correlations between an increased proportion of calcified tissue and corresponding symptoms such as reduced sleep quality or insufficient stability of the circadian system.

Effects and medical uses

Winter depression

In winter, when daylight lasts only a few hours, the daily rhythm of melatonin production can shift and lengthen. As a result, tiredness , sleep disorders and winter depression can occur. As a countermeasure, it is recommended to use the short period of daylight for walks. Alternatively, light therapy can also be used.

Problems sleeping and memory

A melatonin level that is too low can be associated with insomnia. With increasing age, the body produces less melatonin, the average length of sleep decreases and sleep problems occur more frequently (" senile bed escape "). The melatonin balance can also be disturbed by the time change during shift work and long-distance travel ( jetlag ).

Restful sleep is important for a functioning memory . One of the reasons for this could be the influence of melatonin on the hippocampus . This region in the brain is important for learning and remembering. Due to the effects of melatonin, the neurophysiological basis of learning and memory, the synaptic plasticity , is subject to a clear day-night rhythm.

Antioxidant effects of melatonin

In addition to its function of synchronizing the biological clock, melatonin is a powerful radical scavenger and an antioxidant with a broad spectrum of activity. In many underdeveloped creatures, this is the only known function of melatonin. Melatonin is an antioxidant that can easily penetrate cell membranes and the blood-brain barrier.

As an antioxidant, melatonin is a direct radical scavenger for oxygen and nitrogen compounds such as OH, O2 and NO. Melatonin, along with other antioxidants, also works to improve the effectiveness of these other antioxidants. Melatonin has been shown to have twice the antioxidant effects of vitamin E, and it is believed that melatonin is the most potent lipophilic antioxidant. An important feature of melatonin that sets it apart from other classic free radical scavengers is that its metabolites are also free radical scavengers, which is known as a cascade reaction. Melatonin also differs from other classic antioxidants such as vitamin C and vitamin E in that melatonin has amphiphilic properties. Compared to synthetic antioxidants with an effect on the mitochondrion (MitoQ and MitoE), melatonin proved to be a comparable protection against mitochondrial oxidative stress.

Studies on the effects of melatonin on cancer

The systematic review with a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the treatment of solid tumors with melatonin, which was published in the Journal of Pineal Research in November 2005 , resulted in reduced death rates. Melatonin reduced the risk of death within one year to 66% compared to treatment without melatonin. The effect of melatonin was the same with different dosages and also with different types of cancer. No serious undesirable side effects were found. The significant reduction in the risk of death, the low rate of undesirable side effects and the low cost of cancer treatment with melatonin suggest that there is great potential for the use of melatonin in cancer treatment. To confirm the efficacy and safety of melatonin in the treatment of cancer, however, confirmation by other independent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is required.

Clinical studies (review by the National Cancer Institute , May 2013) in kidney, breast, colon, lung, and brain cancers suggest that melatonin has anti-cancer effects in conjunction with chemotherapy and radiation therapy; however, the study results are not entirely clear.

Melatonin for fibromyalgia

Symptoms of fibromyalgia include long-term and widespread pain in muscles, tendons, and connective tissues with no specific cause. One study found that patients had significantly reduced symptoms when they took melatonin alone or in combination with the antidepressant fluoxetine ( Prozac ).

unwanted effects

In the short term - over a maximum period of two to three months - melatonin has hardly any side effects. Occasionally, the following side effects have occurred:

- Drowsiness and lack of concentration

- Irritability, nervousness

- Chest, abdomen and extremities pain, headache

- dizziness

- nausea

- Rashes, itching

For safety reasons, melatonin should not be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding as well as in the case of severe allergies.

If melatonin is taken together with anti-epileptic drugs, antidepressants (SSRIs), and antithrombotic drugs, there may be interactions between the various drugs.

In contrast to short-term administration, the risks and side effects of long-term use are still completely unexplored. For this reason, one should also refrain from taking it continuously.

Melatonin in foods

Melatonin is found in plant-based foods and, in very small quantities, in animal-based foods . Cranberries have the highest melatonin content (up to 9,600 µg / 100 g dry weight). Further sources of melatonin are some types of mushrooms ( Edel-Reizker , common boletus , cultured mushrooms , real chanterelles ), some types of grain ( corn , rice , wheat , oats , barley ), mustard seeds , dried tomatoes and paprika and some types of wine.

The concentration of melatonin in the blood is significantly higher after eating foods containing melatonin. The consumption of melatonin-rich foods has a positive effect on sleep behavior.

| Food | Melatonin content |

|---|---|

| Cranberry, dried | 2,500-9,600 µg / 100 g |

| Noble irritant , dried | 1,290 µg / 100 g |

| Common boletus, dried | 680 µg / 100 g |

| Cultured mushrooms, dried | 430-640 µg / 100 g |

| Corn, dried | 1-203 µg / 100 g |

| Real chanterelle, dried | 140 µg / 100 g |

| Lentil seedlings, dried | 109 µg / 100 g |

| Kidney bean seedlings, dried | 52.9 µg / 100 g |

| Rice, dried | 0-26.4 µg / 100 g |

| Tomato, dried | 25.0 µg / 100 g |

| Mustard seeds, dried | 12.9-18.9 µg / 100 g |

| Wine | 0-13.0 µg / 100 ml |

| wheat | 12.5 µg / 100 g |

| Paprika, dried | 9.3 µg / 100 g |

| oats | 0-9.1 µg / 100 g |

| barley | 0-8.2 µg / 100 g |

| salmon | 0.37 µg / 100 g |

| Eggs, raw | 0.15 µg / 100 g |

| Cow's milk | 0-0.4 ng / 100 ml |

Melatonin is not only produced by humans, but by all mammals in the dark at night, and accordingly also by cows, according to the mechanism described above. In lactation melatonin passes from the blood into the milk . The milk contains different amounts of melatonin depending on the time of day or night and the feed base of the cows. In particular, the return of dairy farming to a special light regime that corresponds to the natural light conditions during the day / night, as well as grass- and herb-based feeding lead to a high nocturnal melatonin level in the cow. If this milk is recorded separately, it contains up to 0.04 micrograms of melatonin per liter. By freeze-drying , the concentration may be 100-fold increased. Compared to some plant foods, the melatonin content is extremely low. The sleep-promoting benefit of whey powder obtained from such milk (so-called "night milk crystals") is scientifically implausible and is assessed differently.

preparations

USA and Canada

Melatonin supplements are available over the counter as dietary supplements in Canada and the United States . Different healing effects are advertised in the USA:

- Migraine prophylaxis

- Stimulation of hair growth

- Scavenging free radicals and as a result of its proven antioxidant abilities:

- a slowdown in aging

- Fighting or preventing cancer ;

- Avoidance of arteriosclerosis , strokes and heart attacks

- Increased secretion of the body's own growth hormones

European Union countries

Melatonin has been approved by the European Commission in the EU as a medicinal product ( Circadin ) for the short-term treatment of primary insomnia (poor sleep quality) in patients aged 55 and over since 2007 . Circadin contains two milligrams of melatonin in a retarded form. The recommended dose is two milligrams one to two hours before bed and after the last meal and should be sustained for three weeks. In Germany, when used as a medicinal substance, melatonin is a prescription substance according to the Medicinal Prescription Ordinance; medicinal products containing melatonin require a prescription regardless of the dose. In many cases, sustained-release melatonin preparations are reimbursable, so that the costs are covered by health insurance.

For use in dietetic foods, melatonin is in accordance with the entry in the Community list drawn up by the European Commission in accordance with Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 (Health Claims) with the health-related information “Melatonin helps to alleviate the subjective feeling of jet lag at. "and" Melatonin helps to shorten the time to fall asleep. " The permissible single dose and the wording for the user information are also specified. This was preceded by corresponding scientific evaluations by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which were published in 2010 and 2011. The inclusion in the community list allows certain health claims for melatonin, but does not mean the approval of melatonin-containing foods. The so-called "health claims" are intended exclusively for food and not for drugs. Such foods are now available as “supplementary balanced diets” in some countries of the European Union (e.g. Austria) with up to 5 mg melatonin per capsule from various manufacturers.

In Germany in 2010 , the Federal Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety (BVL) reported products containing melatonin as “supplementary balanced diets”. Complementary balanced diets are dietary foods . The notification procedure at the BVL does not involve the approval of melatonin-containing products as dietetic foods. The Federal Office forwards the notifications to the official food control of the federal states. This is responsible for complaining about non-marketable products and removing them from the market. There are already approved drugs on the market with a concentration of two milligrams or more of melatonin per daily dose. Whether products with a melatonin concentration of two milligrams or more per daily dose can therefore also be placed on the market as (e.g. dietetic) foods must be checked on a case-by-case basis and is the responsibility of the responsible authorities. There are numerous substances that are used in both medicines and food. Each product has to be checked for itself and a decision has to be made on the classification.

Melatonin preparations were also brought onto the market in Germany as dietary supplements. In 2018, the Munich Administrative Court ruled that a pharmacological effect of melatonin-containing foods was not demonstrable if the recommended dose does not exceed 1 mg per day, and that marketing as a dietary supplement is therefore not illegal.

In Austria, too, products with different dosages are sold as dietary supplements.

Scientific evaluation

There are various studies that prove the good effectiveness of melatonin (here: retarded, i.e. prolonged release of the active ingredient) for people aged 55 and over. Proven effects include the sustainable shortening of the time to fall asleep, the improvement of the quality of sleep and the improvement of morning alertness and daily performance. According to the studies, the main advantage of prolonged-release melatonin is the simultaneous improvement in both sleep quality and morning wakefulness (evidence of restful sleep) in patients with insomnia.

There are also various studies that have examined the effectiveness of melatonin on jet lag symptoms. The data on this are quite different. A large meta-analysis , published in a Cochrane Review, indicates a significant effectiveness of melatonin in a dosage of 0.5 to 5 mg in the treatment of jet lag symptoms. At all of these dosages, melatonin has similar effectiveness. However, less than 5 mg takes the shortest time to fall asleep. The more time zones are crossed, the greater the effect; it is also more pronounced for flights to the east than for flights to the west. These studies examined subjective parameters of sleep, but also other symptoms such as daytime sleepiness and well-being. Another meta-analysis could not find any significant advantage of melatonin in jet lag symptoms. There was no significant shortening of the time to fall asleep in sleep disorders due to shift work. The total duration of sleep could not be significantly increased either. The study also showed that interactions with anti- thrombotic drugs and anti- epileptic drugs are possible. Short-term use of melatonin (<3 months) has no harmful consequences. The selection of the studies (only short-term use, dosage, selected endpoints ) was criticized in this meta-analysis .

Related substances

The substance agomelatine has a chemical structure similar to melatonin . In contrast to melatonin, agomelatine not only has an affinity for the melatonin receptors of the MT 1 and MT 2 types but also antagonistic properties at the serotonin receptor 5-HT 2c . Agomelatine is used as a medicinal substance in the treatment of depression.

Tasimelteon is another substance derived from melatonin that acts as an agonist at MT 1 and MT 2 receptors. Tasimelteon is approved in the EU as an orphan drug for the treatment of sleep-wake disorders with deviations from the 24-hour rhythm in blind people without light perception.

history

Melatonin was discovered and named in 1958 by the US dermatologist Aaron B. Lerner , who already described the sedative effect on humans. In 1990 Franz Waldhauser discovered that the administration of melatonin shortened the early phases of sleep and extended REM sleep .

Analytics

The detection of melatonin is carried out in serum or saliva by means of RIA or ELISA. Alternatively, the melatonin breakdown product 6-hydroxy-melatonin sulfate (6-OHMS) in the urine can be examined in order to determine the nightly melatonin secretion.

literature

- NG Harpsøe, LP Andersen, I. Gögenur, J. Rosenberg: Clinical pharmacokinetics of melatonin: a systematic review. In: European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology . Volume 71, number 8, August 2015, pp. 901-909, doi: 10.1007 / s00228-015-1873-4 , PMID 26008214 (review).

- SM Webb, M. Puig-Domingo: Role of melatonin in health and disease. In: Clinical endocrinology. Volume 42, Number 3, March 1995, pp. 221-234, PMID 7758227 (Review).

- J. Arendt, Y. Touitou: Melatonin and the Pineal Gland: From Basic Science to Clinical Application. Elsevier Science 1993, ISBN 0-444-89583-3 . (standard scientific work on melatonin).

- Arnold Hilgers, Inge Hoffmann: Melatonin . Mosaik Verlag, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-576-10622-7 .

- Walter Pierpaoli, William Regelson: Melatonin - the key to eternal youth, health and fitness . Goldmann Verlag, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-442-12710-6 .

- RKI: Melatonin in environmental medical diagnostics in connection with electromagnetic fields - Communication from the commission "Methods and quality assurance in environmental medicine". 2005.

Web links

- Melatonin effect and side effects ( Memento from February 2, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) - study-based, current article about the melatonin effect and use in the anti-aging area (2011)

- infomed.org/pharma-kritik - Pharma criticism

- How a hormone brings light into the dark. On: Wissenschaft.de of April 25, 2006. Report on a publication in the science magazine PNAS

- The calming secret of red wine. Italian researchers may have discovered why a glass of red wine in the evening is so relaxing. On: Wissenschaft.de from June 19, 2006. Report on a publication in the journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture

- European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) and product information on Circadin ( Memento of March 7, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the European Medicines Agency

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Data sheet melatonin (PDF) from Merck , accessed on January 19, 2011.

- ↑ a b Entry on melatonin in the ChemIDplus database of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM)

- ↑ a b c d Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety : Opinion on Melatonin. (PDF; 286 kB) SCCS / 1315/10, March 24, 2010.

- ↑ SJ Konturek, PC Konturek, T. Brzozowski, GA Bubenik: Role of melatonin in upper gastrointestinal tract . In: J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 58 Suppl 6, December 2007, p. 23-52 , PMID 18212399 ( jpp.krakow.pl [PDF]).

- ↑ Literature research melatonin deficit ( memento of the original from October 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) Clinic for Sleep Medicine at St. Hedwig Hospital, 2009.

- ↑ Tan DX, Chen LD, Poeggeler B, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ (1993): Melatonin: a potent, endogenous hydroxyl radical scavenger , Endocrine J. 1: 57-60, accessed April 29, 2017.

- ↑ a b D. X. Tan, LC Manchester, MP Terron, LJ Flores, RJ Reiter: One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? In: Journal of pineal research. Volume 42, Number 1, January 2007, pp. 28-42, doi: 10.1111 / j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x , PMID 17198536 (Review).

- ^ R. Hardeland: Antioxidative protection by melatonin: multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance. In: Endocrine. Volume 27, Number 2, July 2005, pp. 119-130, doi: 10.1385 / ENDO: 27: 2: 119 , PMID 16217125 (review).

- ^ RJ Reiter, LC Manchester, DX Tan: Neurotoxins: free radical mechanisms and melatonin protection. In: Current neuropharmacology. Volume 8, number 3, September 2010, pp. 194-210, doi: 10.2174 / 157015910792246236 , PMID 21358970 , PMC 3001213 (free full text).

- ↑ B. Poeggeler, S. Saarela, RJ Reiter, DX Tan, LD Chen, LC Manchester, LR Barlow-Walden: Melatonin - a highly potent endogenous radical scavenger and electron donor: new aspects of the oxidation chemistry of this indole accessed in vitro . In: Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Volume 738, November 1994, pp. 419-420, PMID 7832450 .

- ↑ a b M. B. Arnao, J. Hernández-Ruiz: The physiological function of melatonin in plants. In: Plant signaling & behavior. Volume 1, Number 3, May 2006, pp. 89-95, PMID 19521488 , PMC 2635004 (free full text).

- ↑ C. Pieri, M. Marra, F. Moroni, R. Recchioni, F. Marcheselli: Melatonin: a peroxyl radical scavenger more effective than vitamin E. In: Life sciences. Vol. 55, Number 15, 1994, pp. PL271-PL276, PMID 7934611 .

- ↑ DA Lowes, NR Webster, MP Murphy, HF Galley: Antioxidants that protect mitochondria reduce interleukin-6 and oxidative stress, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce biochemical markers of organ dysfunction in a rat model of acute sepsis. In: British journal of anesthesia. Volume 110, number 3, March 2013, pp. 472-480, doi: 10.1093 / bja / aes577 , PMID 23381720 , PMC 3570068 (free full text).

- Jump up ↑ E. Mills, P. Wu, D. Seely, G. Guyatt: Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. In: Journal of pineal research. Volume 39, Number 4, November 2005, pp. 360-366, doi: 10.1111 / j.1600-079X.2005.00258.x , PMID 16207291 (review).

- ↑ PMHDEV: Topics in Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies (PDQ®) - PubMed Health - National Cancer Institute (May 2013). In: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. June 13, 2013, accessed April 29, 2017 . , PMID 26389506

- ^ Hussain SA, Al-Khalifa II, Jasim NA, Gorial FI. Adjuvant use of melatonin for treatment of fibromyalgia. J Pineal Res. 2011 Apr; 50 (3): 267-71. doi : 10.1111 / j.1600-079X.2010.00836.x . Epub 2010 Dec 16.

- ↑ technical information Circadin, as of July, 2015.

- ↑ a b c Xiao Meng, Ya Li, Sha Li, Yue Zhou, Ren-You Gan: Dietary Sources and Bioactivities of Melatonin . In: Nutrients . tape 9 , no. 4 , April 7, 2017, doi : 10.3390 / nu9040367 , PMID 28387721 , PMC 5409706 (free full text).

- ↑ M. Valtonen, L. Niskanen, AP. Kangas, T. Koskinen: Effect of melatonin-rich night-time milk on sleep and activity in elderly institutionalized subjects. In: Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. Vol. 59, 2005, No. 3, pp. 217-221. PMID 16195124 .

- ↑ Night milk crystals against insomnia are nonsense ( Memento of the original from June 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, June 17, 2010.

- ↑ Irene Joy I. dela Peña, Eunyoung Hong, June Bryan de la Peña, Hee Jin Kim, Chrislean Jun Botanas, Ye Seul Hong, Ye Seul Hwang, Byoung Seok Moon, Jae Hoon Cheong: Milk Collected at Night Induces Sedative and Anxiolytic- Like Effects and Augments Pentobarbital-Induced Sleeping Behavior in Mice . In: Journal of Medicinal Food. Volume 18 (2015), Issue 11, pp. 1255–1261. doi : 10.1089 / jmf.2015.3448

- ↑ Milk that is milked at night is said to promote sleep . In: Welt online. 17th October 2010.

- ↑ H. Dustmann, H. Weissßieker, R. Wetendorf: Effectiveness of a milk product with a native increased melatonin content . (PDF) In: The food letter - nutrition up-to-date. Volume 19, 2008, issue 11/12, pp. 320–321.

- ^ S. Miano et al.: Melatonin to prevent migraine or tension-type headache in children. In: Neurological Science. Volume 19, No. 4, September 2008, pp. 285-287. PMID 18810607 .

- ↑ TW Fischer et al.: Melatonin increases anagen hair rate in women with androgenetic alopecia or diffuse alopecia: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. In: British Journal of Dermatology . 2004; 150, pp. 341-345. doi: 10.1111 / j.1365-2133.2004.05685.x

- ↑ RJ Reiter, D. Tan et al .: Melatonin as an antioxidant: biochemical mechanisms and pathophysiological implications in humans (PDF; 981 kB). In: Acta Biochemica Polonica. Vol. 50, No. 4, 2003, pp. 1129-1146.

- ↑ R. Valcavi, M. Zini, GJ Maestroni, A. Conti, I. Portioli: Melatonin Stimulates growth hormone secretion through pathways other than the growth hormone-releasing hormone. In: Clinical endocrinology. Volume 39, Number 2, August 1993, pp. 193-199. PMID 8370132 .

- ↑ AMVV § 1 , No. 1

- ↑ EU Register on Nutrition and Health Claims

- ↑ Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to melatonin and alleviation of subjective feelings of jet lag (ID 1953), and reduction of sleep onset latency, and improvement of sleep quality (ID 1953) pursuant to Article 13 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/20061. In: EFSA Journal. 2010, 8 (2), p. 1467. doi : 10.2903 / j.efsa.2010.1467

- ↑ Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of a health claim related to melatonin and reduction of sleep onset latency (ID 1698, 1780, 4080) pursuant to Article 13 (1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. In: EFSA Journal. 9, 2011, p. 2241, doi : 10.2903 / j.efsa.2011.2241 .

- ↑ Florian Meyer: Melatonin and the contradiction between the Health Claims Regulation and the drug law ( Memento of the original from December 16, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Juravendis law firm , December 8, 2014.

- ↑ On the medicinal properties of foods containing melatonin, VG Munich, judgment v. 10/17/2018 - M 18 K 15.4632. Bavarian State Chancellery, accessed on April 19, 2019 .

- ^ Alan G Wade: Prolonged release melatonin in the treatment of primary insomnia: evaluation of the age cut-off for short- and long-term response. 2010. PMID 21091391 .

- ↑ Remy Luthringer: The effect of prolonged-release melatonin on sleep measures and psychomotor performance in elderly patients with insomnia . 2009. PMID 19584739 .

- ↑ Patrick Lemoine: Prolonged-release melatonin improves sleep quality and morning alertness in insomnia patients aged 55 years and older and has no withdrawal effects . 2007. PMID 18036082

- ^ Alan G Wade: Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: a randomized placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety. In: BMC Medicine. 2011.

- ↑ A. Herxheimer, KJ Petrie: Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag. In: Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1, 2001, p. CD001520.

- ↑ N. Buscemi et al .: Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: meta-analysis. In: British Medical Journal . Volume 332, 2006, pp. 385-393. PMID 16473858

- ^ Richard J. Wurtman, Franz Waldhauser, Harris R. Lieberman: The Secretion and Effects of Melatonin in Humans . In: The Pineal Gland and its Endocrine Role pp. 551-573 doi : 10.1007 / 978-1-4757-1451-7_29 .

- ↑ P. Levallois, M. Dumont et al. a .: Effects of electric and magnetic fields from high-power lines on female urinary excretion of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin. In: American journal of epidemiology. Volume 154, Number 7, October 2001, pp. 601-609. PMID 11581093 .

- ↑ DH Pfluger, CE Minder: Effects of exposure to 16.7 Hz magnetic fields on urinary 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate excretion of Swiss railway workers. In: Journal of Pineal Research . Volume 21, Number 2, September 1996, pp. 91-100. PMID 8912234 .

- ↑ E. Gilad, N. Zisapel: High-affinity binding of melatonin to hemoglobin. In: Biochemical and molecular medicine. Volume 56, Number 2, December 1995, pp. 115-120. PMID 8825074 .

- ↑ DK Lahiri, D. Davis et al. a .: Factors that influence radioimmunoassay of human plasma melatonin: a modified column procedure to eliminate interference. In: Biochemical medicine and metabolic biology. Volume 49, Number 1, February 1993, pp. 36-50. PMID 8439449 .